Architecture

From modernist marvels, to heavenly houses, and the breaking news breaking new ground, this is your one-stop shop for the finest building design

Explore Architecture

-

A compact Scottish home is a 'sunny place,' nestled into its thriving orchard setting

Grianan (Gaelic for 'sunny place') is a single-storey Scottish home by Cameron Webster Architects set in rural Stirlingshire

By Tianna Williams Published

-

Porthmadog House mines the rich seam of Wales’ industrial past at the Dwyryd estuary

Ström Architects’ Porthmadog House, a slate and Corten steel seaside retreat in north Wales, reinterprets the area’s mining and ironworking heritage

By Léa Teuscher Published

-

Mexico's Office of Urban Resilience creates projects that cities can learn from

At Office of Urban Resilience, the team believes that ‘architecture should be more than designing objects. It can be a tool for generating knowledge’

By Michael Snyder Published

-

This retreat deep in the woods of Canada takes visitors on a playful journey

91.0 Bridge House, a new retreat by Omer Arbel, is designed like a path through the forest, suspended between ferns and tree canopy in the Gulf Island archipelago

By Léa Teuscher Published

-

Top 25 houses of 2025, picked by architecture director Ellie Stathaki

This was a great year in residential design; Wallpaper's resident architecture expert Ellie Stathaki brings together the homes that got us talking

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

These Guadalajara architects mix modernism with traditional local materials and craft

Guadalajara architects Laura Barba and Luis Aurelio of Barbapiña Arquitectos design drawing on the past to imagine the future

By Ana Karina Zatarain Published

-

Inside architect Andrés Liesch's modernist home, influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright

Andrés Liesch's fascination with an American modernist master played a crucial role in the development of the little-known Swiss architect's geometrically sophisticated portfolio

By Adam Štěch Published

-

This Mexican architecture studio has a surprising creative process

The architects at young practice Pérez Palacios Arquitectos Asociados (PPAA) often begin each design by writing out their intentions, ideas and the emotions they want the architecture to evoke

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

A former fisherman’s cottage in Brittany is transformed by a new timber extension

Paris-based architects A-platz have woven new elements into the stone fabric of this traditional Breton cottage

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

The architecture of Mexico's RA! draws on cinematic qualities and emotion

RA! was founded by Cristóbal Ramírez de Aguilar, Pedro Ramírez de Aguilar and Santiago Sierra, as a multifaceted architecture practice in Mexico City, mixing a cross-disciplinary approach and a constant exchange of ideas

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

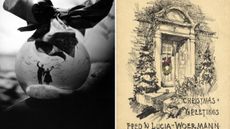

These Christmas cards sent by 20th-century architects tell their own stories

Handcrafted holiday greetings reveal the personal side of architecture and design legends such as Charles and Ray Eames, Frank Lloyd Wright and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

By Anna Solomon Published

-

This Fukasawa house is a contemporary take on the traditional wooden architecture of Japan

Designed by MIDW, a house nestled in the south-west Tokyo district features contrasting spaces united by the calming rhythm of structural timber beams

By Tianna Williams Published

-

The RIBA Asia Pacific Awards reward impactful, mindful architecture – here are the winners

The 2025 RIBA Asia Pacific Awards mark the accolade’s first year – and span from sustainable mixed-use towers to masterplanning and housing

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

A day in Ahmedabad – tour the Indian city’s captivating architecture

India’s Ahmedabad has a thriving architecture scene and a rich legacy; architect, writer and photographer Nipun Prabhakar shares his tips for the perfect tour

By Nipun Prabhakar Published

-

Take a tour of the 'architectural kingdom' of Japan

Japan's Seto Inland Sea offers some of the finest architecture in the country – we tour its rich selection of contemporary buildings by some of the industry's biggest names

By Kanae Hasegawa Published

-

Rent this dream desert house in Joshua Tree shaped by an LA-based artist and musician

Casamia is a modern pavilion on a desert site in California, designed by the motion graphic artist Giancarlo Rondani

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

Arbour House is a north London home that lies low but punches high

Arbour House by Andrei Saltykov is a low-lying Crouch End home with a striking roof structure that sets it apart

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Inside a creative couple's magical, circular Indian home, 'like a fruit'

We paid a visit to architect Sandeep Virmani and social activist Sushma Iyengar at their circular home in Bhuj, India; architect, writer and photographer Nipun Prabhakar tells the story

By Nipun Prabhakar Published

-

Taiwan’s new ‘museumbrary’ is a paradigm-shifting, cube-shaped cultural hub

Part museum, part library, the SANAA-designed Taichung Green Museumbrary contains a world of sweeping curves and flowing possibilities, immersed in a natural setting

By Danielle Demetriou Published

-

Step inside this resilient, river-facing cabin for a life with ‘less stuff’

A tough little cabin designed by architects Wittman Estes, with a big view of the Pacific Northwest's Wenatchee River, is the perfect cosy retreat

By Ali Morris Published

-

RIBA House of the Year 2025 is a ‘rare mixture of sensitivity and boldness’

Topping the list of seven shortlisted homes, Izat Arundell’s Hebridean self-build – named Caochan na Creige – is announced as the RIBA House of the Year 2025

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

In addition to brutalist buildings, Alison Smithson designed some of the most creative Christmas cards we've seen

The architect’s collection of season’s greetings is on show at the Roca London Gallery, just in time for the holidays

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

In South Wales, a remote coastal farmhouse flaunts its modern revamp, primed for hosting

A farmhouse perched on the Gower Peninsula, Delfyd Farm reveals its ground-floor refresh by architecture studio Rural Office, which created a cosy home with breathtaking views

By Tianna Williams Published

-

Remembering Robert A.M. Stern, an architect who discovered possibility in the past

It's easy to dismiss the late architect as a traditionalist. But Stern was, in fact, a design rebel whose buildings were as distinctly grand and buttoned-up as his chalk-striped suits

By Nick Mafi Published

-

Wallpaper* gift guides: architecture expert Ellie Stathaki would like…

Architecture & environment director Ellie Stathaki talks us through her shopping wish list for festive gift inspiration, and beyond

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

A new bungalow in Ljubljana is infused with the spirit of place

A bungalow set in the pioneering low-rise eco development of Murgle, the House under the Poplars trades grand architectural gestures for quiet innovation

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

A Dutch visitor centre echoes the ‘rising and turning’ of the Wadden Sea

The second instalment in Dorte Mandrup’s Wadden Sea trilogy, this visitor centre and scientific hub draws inspiration from the endless cycle of the tide

By Alisa Larsen Published