Discover Canadian modernist Daniel Evan White’s pitch-perfect homes

Canadian architect Daniel Evan White (1933-2012) had a gift for using the landscape to create extraordinary homes; revisit his story in an article from the Wallpaper* archives (first published in 2011)

Vancouver-based architect Daniel Evan White was never a follower of style or trend. He marched to his own inner design drum, producing dozens of exquisitely executed houses, and a handful of public projects, largely confined to coastal British Columbia.

'In a way, Dan was a post-postmodernist,' says long-time client Maureen Lunn, who has had two residences designed by White. While he hit his stride in the 1980s, just as fussy post-modern flourishes like arches and colonnades were gaining in popularity, White stuck resolutely to his modernist principles of clean, simple lines, bold geometry and Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired organic architecture. His uncompromising approach may have been considered unfashionable at the time, but he has since acquired a cult-like following among earnest young architecture students and a whole new generation of aesthetic purists.

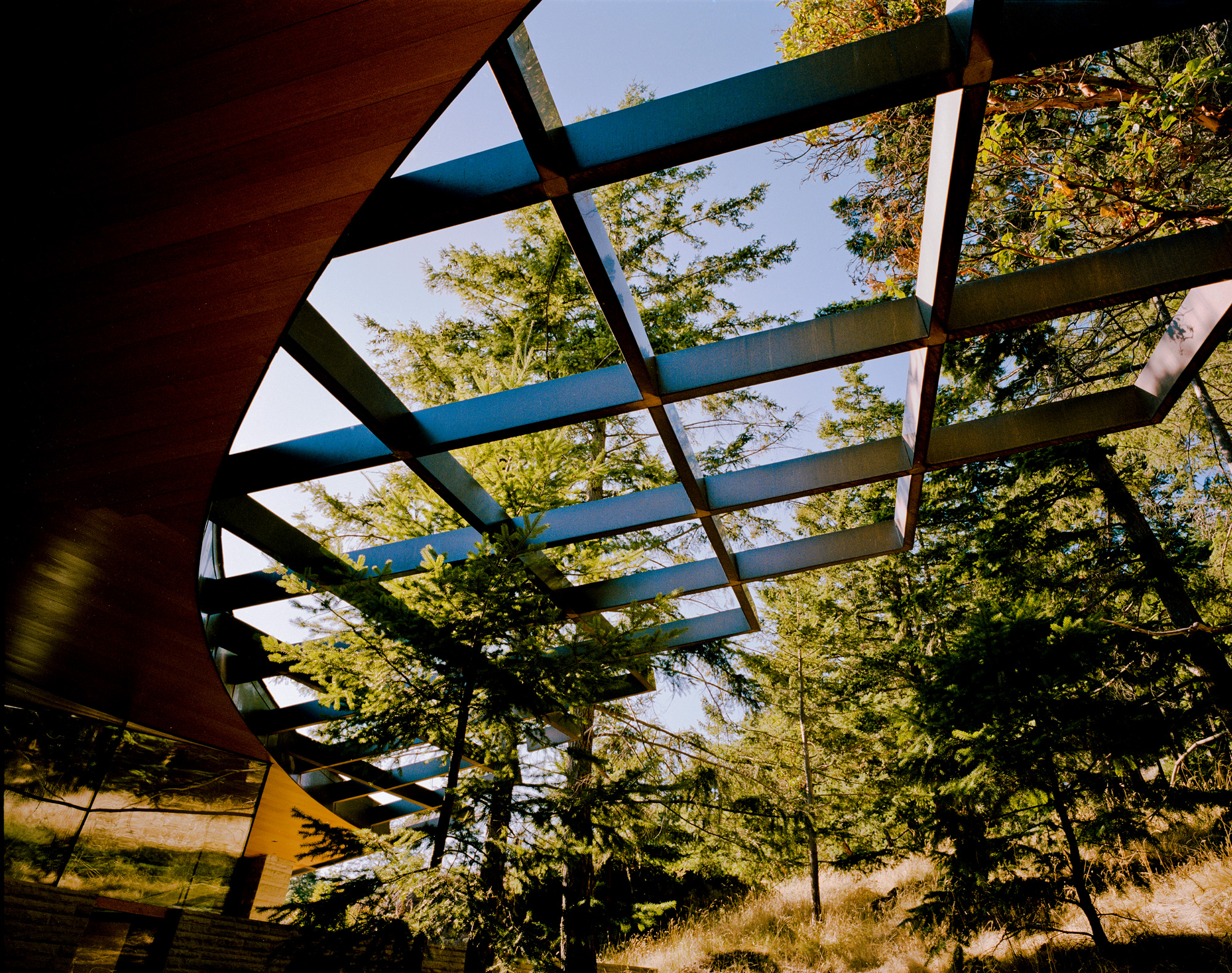

Taylor House

Enter the world of Canadian modernist Daniel Evan White

Seventy-seven and retired at the time of writing (the architect would pass away a year later, in 2012), White spent his working life designing deceptively simple yet complex structures that defied conventional wisdom – and often gravity – frequently for seemingly impossible sites. Homes on remote islands, on steeply graded cliff sides, at the ocean's edge, residences that emerged out of ancient bedrock, surrounded by forest and soaring into the Canadian sky. They celebrated and, indeed, amplified the beauty of their sites, but they were also noted for an intellectually rigorous aesthetic where precision and symmetry were counterbalanced by dramatic sculptural form.

‘Dan emerged on top of a rock above a 6m-high cliff face and spread his arms, proclaiming, “the house must span across this gulley, creek and all”’

Client and bridge engineer Peter Taylor

There was nothing shy or retiring about White's design, or his daring engagement with wilderness sites. However, his colleague Russell Cammarasana recalls that his former mentor ‘had absolutely no interest in self-promotion’. As a result, White's work is largely unrecorded. There are some images, but no project descriptions, save for a couple of articles in provincial magazines, and very little architectural criticism. Cammarasana and White’s family share the archive of his hand-drawn sketches and plans. He never used computer-generated images, and for many years his office was an unassuming coach house with a bare light bulb hanging from the ceiling.

Connell cabin

Unlike his friend and one-time architecture professor Arthur Erickson (behind projects such as Eppich House and the lesser-known Perry Estate), White received almost no international commissions. Instead, he was content building off-grid and out of the public eye. If Erickson had more in common with the flamboyance of his patron, former prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, White was more the Glenn Gould of Canadian architecture. In many ways, he lived in his own world. 'Working in his office often felt like living in a bubble,' says Cammarasana.

'Dan had a kind of childlike innocence,' says Lunn. 'He was an artist, [in fact, White started out as a painter before entering architecture school in his early twenties] not a businessman.' Despite his love of beauty and luxury, and his many wealthy clients, he faced constant financial struggles, and sadly was never able to build a house for his own family.

Connell cabin

In a neat trick of Wright-inspired sacred-geometry-meets-a-child's-fort, the Connell cabin is planned as a hexagon

But he was absolutely dedicated to his craft and to his clients. 'Dan was the kind of architect people with impossible sites and unrealistic budgets would approach,' says Cammarasana. 'And he never let them down.' When bridge engineer Peter Taylor and his wife Gillian acquired a waterfront property in West Vancouver in the mid-1970s – a steeply graded, semi-wild forested site that dropped dramatically down to the ocean –they turned to White for a residential design that would work on the site.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

'Dan marched around for a while in the thick bush,' recalls Peter Taylor. 'He eventually emerged on top of a rock above a 6m-high cliff face and expansively spread his arms, proclaiming, “the house must span across this gulley, creek and all”. Gillian and I contemplated this breathtaking concept and then informed Dan that it was a crazy idea. However, Dan persevered. After a topographical survey of the lot, the architect prepared a relief model of the site and inserted a model of the house: it was a perfect fit.

Lunn House

Indeed, the resulting residence, built from concrete, glass and wood, fuses seamlessly with its site despite its generous 269 sq m. The two-storey edifice was conceived as a long, narrow bridge-like structure that spans a small ravine and is anchored to the granite rocks that embrace it. A stream flows beneath it, the run-off framed by the house as it cascades down to the ocean.

The journey to the Taylor house begins with a walk down a paved road – thick forest 30 years ago – at a steep, almost right-angled incline. Flanked by landscaping featuring a mix of native plants, both wild and tamed, the first glimpse of the house from the north side is magical: a wall of sloped glazing through which the sea can be seen via a second layer of south-facing windows.

The transparency of the approach is countered by an intimate, almost cave-like entrance area, an alcove that acts as a refuge from the open water. A large, solid hemlock door opens for the big reveal: a breathtaking view of a heart-pounding 12m drop to the seafront below.

Lunn House

While the north-facing entrance to the house draws one in, its south, sea-facing façade is the most monumental. Designed to appear as if it had been carved from the cliff, it features a long, steep, concrete and steel stairwell that seemingly floats in mid-air. The walk down (and much of the interior journey) is marked by framed views of the landscape, and at the end, a pathway leads to the ravine that the house straddles, and a platform shaped like a mini amphitheatre opens up to the seafront.

While some essential principles of organic modernism imbue all of White's work, each of his houses is notable for its utterly unique form. When the McIlveens asked White to design a floating home for them in semi-rural Delta, just south of Vancouver, in the late 1980s, he created a child's toy of a house on a tiny 9m x 12m footprint. Using a variety of geometric shapes, the rigorous composition of cubes, cylinders and spheres is arranged around a series of interlocking L-shaped columns rising up the full three floors of the home and anchoring it in an essential tension between the orthogonal and the oblique.

By setting the Mcllveen house at a 45-degree angle to the site, he ensured privacy from neighbouring homes and oriented the house west towards river and sea views, creating a heightened sense of spaciousness. With a simple palette of red cedar, glass and terracotta tiles, he created a unique space that plays with solidity and transparency throughout.

Lunn House

The first of two helix-like stairwells winds its way from a hooded, inward-looking first floor to the second floor that explodes into a light-saturated open living space. A curvilinear enclosed balcony offers a view of the water, while the kitchen curves out toward east-facing glazing. Above it looms a large cedar sphere, studded with recessed lights, that contains the third-floor master bathroom and sauna. At night, the giant orb appears luminescent, and from a distance, the house looks rather like a Kashmiri pavilion set on the moon.

The cedar orb of the McIlveen House’s master bath hovers, like a West Coast version of the orgasmatron from Woody Allen's Sleeper

A walk up the second spiral staircase reveals a different aquatic view with each tread, while the semi-circular balcony, framed by rectangular hoops, opens up to the coastal scenery. The cedar orb of the master bath hovers nearby, like a West Coast version of the orgasmatron from Woody Allen's Sleeper. On the other side of the bath, the snug master bedroom reads like the lair of a vaguely psychedelic sea captain. This is a floating home that dares to domesticate the ephemeral.

Mcllveen House

To say that his approach to residential design was unique is perhaps an understatement. When White was asked by his friends Gavin and Lynne Connell to build a cottage on Galiano Island in the early 1970s, his response was to subvert the traditional cabin by designing a home formed from a series of vertically oriented logs arranged in three circles. In a neat trick of Wright-inspired sacred-geometry-meets-a-child's-fort, the house is planned as a hexagon. The outer structure consists of three identical entranceways with floating cedar log stairwells, like ceremonial steps to a woodsy ziggurat. In between each are three decks framed by a circle of logs that extends all the way up to the roof. While the house appears like a log fortress from a distance, most of the outside walls are clear glazing, and light spills down from the Plexiglas-studded roof.

The house is marked by a fusion of inside and outside, with specially angled glass corners that fool many visitors into confusing the two. Weight-bearing log columns with fitted slats are split in two by the glazing. At night, when the logs are lit, the distance between the two spaces disappears altogether.

Sadly, White was too ill to finish his ten-year-in-the-making masterpiece, the Lunn residence on Bowen Island, and it was left to Cammarasana to execute White's design. The handcrafted, custom-designed interior, which reads like couture architecture, is exquisite. But the exterior, set on a 111-acre semi-wild site, is pure sculpture.

Mcllveen House

Placed so as to maximise the stunning sea view and nestled into a natural depression in the rocky landscape, the house's defining feature is its bronze, hyperbolic paraboloid roof, which defines the dynamic interior spaces. From the road, the house is almost invisible, but it gradually opens up counterclockwise to reveal a three-storey edifice with wraparound decks of cantilevered glass that embrace the surrounding landscape.

The interior is defined by a floating spiral staircase that descends into the library, contrasting with three glazing-heavy rooms that open up to the water views. Like many of White's residences, the house is a study in symmetrical precision and pitch-perfect siting. His houses have an explicit relationship with their surroundings, their robust forms simultaneously modern and timeless. 'White was a man of few words,' says Lunn. Instead, his legacy is more than capable of speaking for itself.

A version of this article was first published in the December 2011 issue of Wallpaper*