Before he was a fashion supernova, Virgil Abloh was an architecture student. Here's how it shaped him

In this exclusive book excerpt, Pulitzer Prize-winning fashion critic Robin Givhan explores modernism's enduring influence

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Like so many young people from the Midwest who had big dreams, like so many American fashion designers before him, Virgil Abloh looked east to find his future. He cast his gaze toward Chicago, the city of house music and hip-hop, the Magnificent Mile and the South Side, Jesse Jackson and Barack Obama, midcentury and modernist buildings.

Abloh went to Chicago to study architecture – a field that influenced the way he engaged with his own creativity and the imaginings of others. The city introduced Abloh to the buildings of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, whose work would be an enduring inspiration.

The architecture school at the Illinois Institute of Technology, where Abloh studied, was one of the most famous in the world, not just because of the quality of the education students received there, which was top-notch, but because of the main building that housed it. S. R. Crown Hall, designed by the widely admired van der Rohe, was built in 1956. It stood as a masterpiece of modernism and has been described as 'the architectural father of open-space buildings.' It was the structure that sent generations of homebuyers and HGTV fanatics on the hunt for open-concept dwellings and turned everyone into an expert on “flow.” In 1982 the U.S. Postal Service issued a twenty-cent stamp featuring Crown Hall, and in 2001 Interior Secretary Gale Norton declared it a national historic landmark.

Crown Hall, pictured here in 1953.

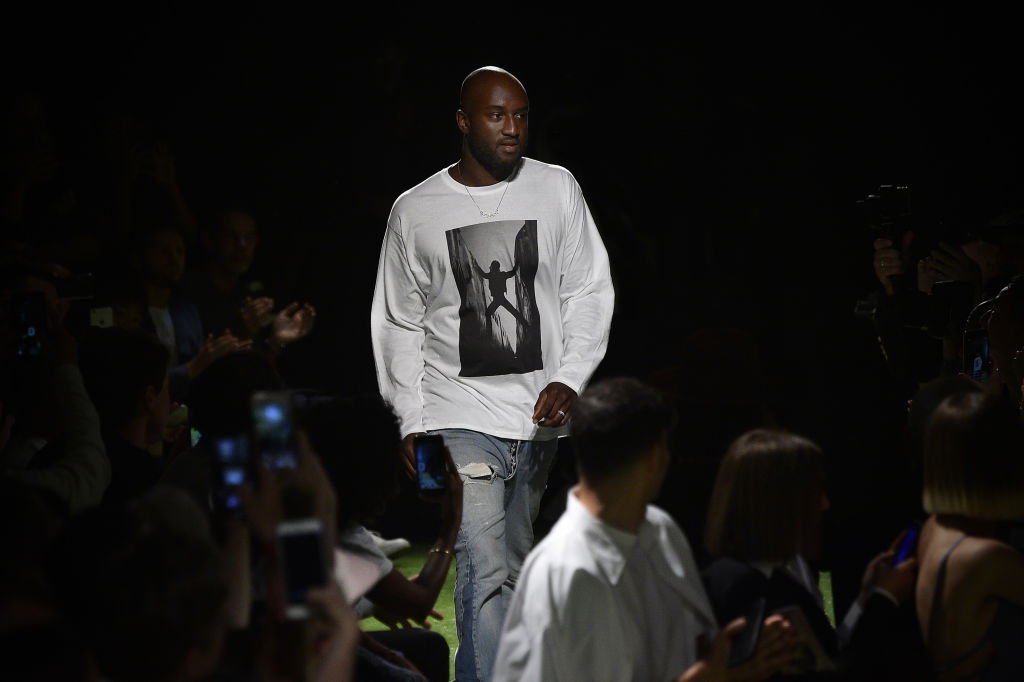

Virgil Abloh in 2019, on the Pont Neuf, Paris, with his Mies van der Rohe-inspired metal mesh ‘Color Gradient Chair’ (2018). Photographed for the June 2019 issue of Wallpaper* by Marvin Leuvrey.

Van der Rohe himself helmed the College of Architecture from 1938 to 1958 and oversaw the development of the campus. IIT bore van der Rohe’s imprimatur in its buildings and in the architecture school’s curriculum, which emphasised understanding materials, constructing three-dimensional models, and following the philosophy that 'less is more' and 'God is in the details.' When Virgil Abloh stepped through the doors of Crown Hall for the first time as a graduate student in 2003, he was mesmerised by the building’s design and its clarity of purpose. He didn’t know why he was so captivated; he knew next to nothing about van der Rohe, who’d died in Chicago in 1969. But he knew the building was special, and he was intrigued and energized by its spirit.

Abloh was fresh from his undergraduate graduation at the University of Wisconsin, where he’d earned a degree in civil engineering. Neither of those data points—his alma mater or his major—had been something about which he was passionate. His parents encouraged him, told him, to study engineering. Like so many children of African immigrants, he was expected to enter one of three fields: law, medicine, or engineering. They were careers that immediately commanded respect. To practice law was to be presumed a success. A doctor was heroic. Engineers built things. There was nothing fuzzy or scattershot about these professions.

The decision to become a University of Wisconsin badger was a matter of geography and timing. The school was just over an hour’s drive north from Rockford, and since Abloh had missed the deadline to apply to the engineering school at the University of Illinois, he turned to Wisconsin, which had a later deadline. While in Wisconsin, Abloh divided his time between deejaying—something that had captured his imagination in high school and had given his mother Eunice heartburn—and schoolwork. His mother literally cried when she realized something so whimsical was getting a significant share of his attention. She worried even more when he installed a turntable in his dorm room. But he was a good student, suffering through advanced mathematics and all, so she couldn’t really complain. Music and skateboarding were his creative outlets.

Then, just before graduating, he discovered a new one. He took his first art history class. It focused on the Renaissance, a period in European painting stretching from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries and including artists such as Raphael, Michelangelo, and Leonardo da Vinci—an early multihyphenate. He also discovered Caravaggio and his manipulation of light and shadow known as chiaroscuro. He was excited to learn that the artist, who had begun working at the end of the Renaissance period, had helped to usher in a completely new style of painting. An artist changed the way people thought.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Abloh made his way to architecture because it was both a creative pursuit and a practical one. It was a method of problemsolving within an aesthetic context, and it was a natural extension of his undergraduate education. 'Architecture would be my bridge between the rational world of engineering and these emotive forms I was always drawn to,' Abloh said.

Abloh, photographed for the June 2019 issue of Wallpaper* by Marvin Leuvrey.

At the Illinois Institute of Technology, Abloh enrolled in a course of study designed for those who were coming to architecture as fully formed professionals working in a different field or as graduates who’d received their bachelor’s degree in another subject. The rigorous three-year program was intended to give students the tools and education they needed to become a licensed architect, or to at least think like one.

'The interesting part about architecture training, in my opinion, is you learn to present. You learn to present the work for design reviews,' said Frank Flury, an associate professor at the college of architecture who had Abloh as a student. 'It doesn’t make a big difference if you’re a painter, an architect, or a salesman. The important part is that you learn to present. This is a very important part of our discipline and why some people study architecture.

'They learn to dress properly, go out to talk to people, to be self-confident—because if you need to sell your idea or your design project, you need to be convincing to people.'

[Flury] had worked with hundreds of students. Yet he remembered Abloh. In part, this was because Abloh was a visual curiosity. To an architecture professor who was a study in unremarkable neutrals, Abloh’s clothes were offbeat concoctions, like a hoodie with fur stitched around its edges. Abloh, who’d become more attuned to fashion as a college student freed from the formality of Boylan High School, conjured his clothes from his imagination, and his mother realized them with her sewing expertise. But his building models also stood apart from those of his peers.

'I wouldn’t say he was necessarily the top architect or designer, but he was always very, very much interested in graphic design. So his drawings were all always compositionally very, very interesting,' Flury said. 'The scale was different. . . . He designed and made things a little different than other students.'

Abloh never intended to work as an architect, something he never explicitly confided to his parents. But he expressed a kinship with its method of problem-solving and its creativity. He enjoyed intellectualising, theorising, and hypothesising. He could expound on anything. He had a compulsion to explain. He was fond of the word practice, as both a noun and a verb. He used it as a way of describing his work in fashion: he was applying ideas and theories to real-world situations. With fashion he took disconnected notions on a mood board or laptop and turned them into garments. 'I liked the idea of taking a program, thinking of a solution and being able to defend it,' he said. 'I think I always had a sense of how to internalize that method and apply it somewhere else.'

Unlike many of his peers in the fashion industry, Abloh was at peace with the fact that everything he produced was not in its perfect form. It was, after all, a practice. Everything was a work in progress.

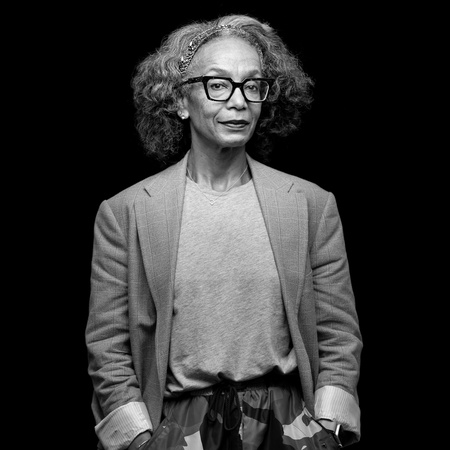

The author, Robin Givhan

Excerpted from MAKE IT OURS: Crashing the Gates of Culture with Virgil Abloh by Robin Givhan. Copyright 2025 by Robin Givhan. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Robin Givhan's biography of Virgil Abloh, will be released 24 June.