Watches & Jewellery

Power jewels, timeless watches, style on all fronts – the Wallpaper* view on the stuff that adorns you

Explore Watches & Jewellery

-

The new Tudor Ranger watches master perfectly executed simplicity

The Tudor Ranger watches look back to the 1960s for a clean and legible design

By James Gurney Published

-

Five watch trends to look out for in 2026

From dial art to future-proofed 3D-printing, here are the watch trends we predict will be riding high in 2026

By Thor Svaboe Published

-

Georgia Kemball's jewellery has Dover Street Market's stamp of approval: discover it here

Self-taught jeweller Georgia Kemball is inspired by fairytales for her whimsical jewellery

By Belle Hutton Published

-

Click to buy: how will we buy watches in 2026?

Time was when a watch was bought only in a shop - the trying on was all part of the 'white glove' sales experience. But can the watch industry really put off the digital world any longer?

By Josh Sims Published

-

Dive into Buccellati's rich artistic heritage in Shanghai

'The Prince of Goldsmiths: Buccellati Rediscovering the Classics' exhibition takes visitors on an immersive journey through a fascinating history

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Love jewellery? Now you can book a holiday to source rare gemstones

Hardy & Diamond, Gemstone Journeys debuts in Sri Lanka in April 2026, granting travellers access to the island’s artisanal gemstone mines, as well as the opportunity to source their perfect stone

By Anna Solomon Published

-

Let’s hear it for the Chopard L.U.C Grand Strike chiming watch

The Swiss watchmaker’s most complicated timepiece to date features an innovative approach to producing a crystal-clear sound

By Bill Prince Published

-

10 watch and jewellery moments that dazzled us in 2025

From unexpected watch collaborations to eclectic materials and offbeat designs, here are the watch and jewellery moments we enjoyed this year

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Why are the most memorable watch designers increasingly from outside the industry?

Many of the most striking and influential watches of the 21st century have been designed by those outside of the industry’s mainstream. Is it only through the hiring of external designers that watch aesthetics really move on?

By Josh Sims Published

-

Next-generation jeweller Rosalie Carlier is one to watch

The young jewellery designer creates sensuous but bold pieces intended to ‘evoke emotion in the wearer’

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Six beautiful books to gift the watch and jewellery lover

From an encyclopaedic love letter to watchmaking to a celebration of contemporary jewellery, these tomes are true gems

By Milena Lazazzera Published

-

Design is key in TAG Heuer’s end-of-year watch releases

TAG Heuer is embracing exciting materials and new collaborations, capping off a big year; discover the new Fragment and Monaco limited editions

By James Gurney Published

-

A. Lange & Söhne's new Bond Street flagship merges German charm with Mayfair poise

The celebrate the launch of its handsome new home, the brand's releasing an equally elegant new watch

By Thor Svaboe Published

-

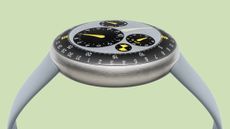

Take an exclusive look inside Marc Newson and Ressence’s new watch collaboration

A serendipitous collaboration between innovative watch brand Ressence and Marc Newson dials up on the industrial designer’s earlier cult offerings

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Add a pop of colour to your wrist this season with these bold watches

Brightly coloured watches, from Rolex, Omega, Patek Philippe and more, are just the thing for the winter season

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Hublot and Daniel Arsham make a splash

The Hublot MP-17 MECA-10 Arsham Splash Titanium Sapphire watch rethinks a traditional design

By Simon Mills Published

-

The gold watches to covet now

Gold watches from H Moser & Cie, Fears and Patek Philippe are on our radar for 2026

By Josh Sims Last updated

-

Cartier pays tribute to ancient myths in Rome exhibition

In ‘Cartier & Myths at the Capitoline Museums’, Cartier looks to its rich history of drawing inspiration from the ancient world

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Van Cleef & Arpels celebrates the early flowering of its art deco jewellery designs with an exhibition in Tokyo

Van Cleef & Arpels nod back to an illustrative Art Deco history with an exhibition celebrating its influence

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Get the glow: the best luminescent watches

Is luminescence the next artistic edge in watchmaking? Here’s how brands from MB&F to Schofield, IWC, Bamford and Bell & Ross are developing exciting, glowing watches

By Josh Sims Published

-

At Dubai Watch Week, brands unveil the last new releases of the year

Brands including Chopard, Louis Vuitton, Van Cleef & Arpels present new watches at Dubai Watch Week

By James Gurney Published

-

These statement watches are surefire conversation starters

From Richard Mille to Hublot and Bulgari, these statement watches aren’t to be missed

By Chris Hall Last updated

-

Who won big at the GPHG, the Oscars of the watch world

Wallpaper* editor-in-chief and Grand Prix d’Horlogerie Genève jury member Bill Prince on the watch world’s 2025 winners

By Bill Prince Published

-

Friction-free movements will revolutionise the watch industry – why don't we have them yet?

Oil is the reason your mechanical watch requires periodic (and expensive) servicing. Finding ways to do without it altogether remains, as it has been since the 1700s, the holy grail of watchmaking

By Josh Sims Published

-

Inside Coreen Simpson’s fabulous, jewellery- and art-filled world

To mark the publication of ‘Coreen Simpson: A Monograph’, we meet the octogenarian photographer and jewellery designer over Zoom, and take a deep dive into her world

By Sarah Moroz Published

-

Punk, pearls and politics: a new book pays tribute to Vivienne Westwood's glorious jewellery

'Vivienne Westwood & Jewellery' is the first book to focus on the designer’s jewellery creations

By Hannah Silver Published

-

The Japanese watch brands you need to know now

Naoya Hida & Co, Kikuchi Nakagawa and Kurono Tokyo are just some of the Japanese watch brands to keep an eye on

By Thor Svaboe Last updated