Lina Bo Bardi, the misunderstood modernist, and her influential architecture

A sense of mystery clings to Lina Bo Bardi, a modernist who defined 20th-century Brazilian architecture, making waves still felt in her field; here, we explore her work and lasting influence

Designed by Lina Bo Bardi and built between 1957 and 1968, São Paulo’s MASP (Museu de Arte de São Paulo) is an architectural revelation: a huge glass-fronted volume suspended above the street by four stark crimson pillars, a dramatic urban gesture echoing above and below ground. You tend to remember the first time you encounter a building authored by the architect who will go on to shape your passion for the field, and for this humble design writer, that moment came with a visit to that building nearly 20 years ago. For the twenty-something humanities student I was at the time, MASP turned my idea of what architecture could be upside down. Like the modernist architecture master herself, the building resists convention and easy definition.

Lina Bo Bardi

Lina Bo Bardi: a pioneering modernist

Italian émigré Bo Bardi arrived in Brazil in 1946 and has since become a symbol of Brazilian modernism and cultural identity. Yet her path to recognition was neither straight nor assured. Overlooked for much of her career and posthumously misunderstood, her work was too often diminished by reductive readings of her gender or limited output; she thus remained a marginal figure in modernist architectural history until relatively recently.

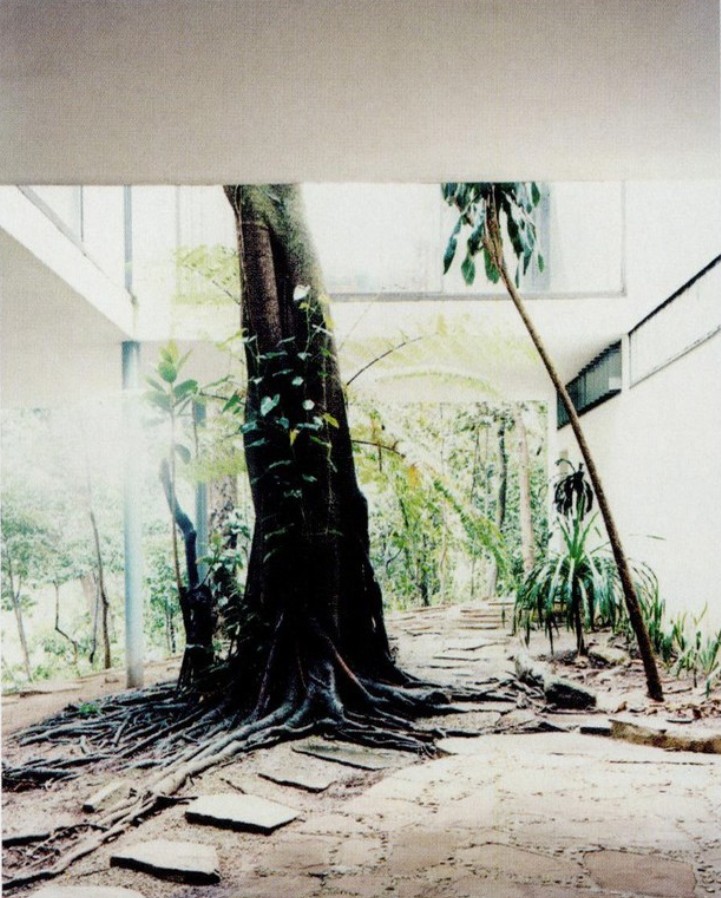

Shot for Wallpaper’s June 2010 'Born in Brazil' issue, which was dedicated entirely to the country, Casa de Vidro (Glass House) is built on pilotis, so it appears to float above the landscaped wilderness

The architect, Lina Bo Bardi

Lina Bo Bardi was born in 1904 in Rome, Italy. As a recent graduate from the Rome College of Architecture, she worked with Carlo Pagani and Gio Ponti, and she later served as deputy director of Domus magazine. She married art critic and journalist Pietro Maria Bardi in 1946, and together, they moved to Brazil later that same year, where Bo Bardi set up her architecture practice.

While the majority of her work remained lesser known outside specialist circles for most of the 20th and early 21st centuries, the last decade has seen Bo Bardi take her rightful place in the canon of Brazilian, and indeed world, architecture. Still, a sense of mystery clings to her – a mystique that may well have been of her own design. More than an architect, she was a cultural anthropologist of sorts, intent on channelling what she, the wide-eyed Italian arrival, saw to be the true soul of Brazil, into her work. Her deep fascination with the traditions and crafts of the country’s poorer and remote north-east regions, particularly Bahia, informed her designs in ways that went far beyond form or style.

From the same, June 2010, issue of Wallpaper*, Bo Bardi’s studio, in the grounds of Glass House, displays drawings, books and posters

In 2019, British filmmaker and artist Sir Isaac Julien captured this complexity in Lina Bo Bardi – A Marvellous Entanglement, casting mother-and-daughter Brazilian cinema legends Fernanda Montenegro and Fernanda Torres to paint a dual portrait of Bo Bardi. The resulting poetic homage cemented Bo Bardi's revered posthumous status.

Her built legacy may be modest in numbers – just 20 realised projects, all in Brazil – but it brims with vision, audacity, and care. Her drawings, writings, and what can only be described as spirit, continue to reverberate through the culture and architecture of her adopted homeland. In what follows, we explore six of her completed works. Few in number, perhaps, but each one reveals an intensity of thought and a commitment to society, art and architecture that makes it unforgettable.

Marcio Kogan – photographed for our Wallpaper* Guest Editors’ 2024 issue by Eudes de Santana – in the auditorium at São Paulo’s SESC Pompéia factory building, designed by Lina Bo Bardi in 1986

Lina Bo Bardi: 6 key projects

Casa de Vidro

Italian fashion house Bottega Veneta's ‘The Square’ project is a travelling cultural series that seeks to provide a dialogue with countries around the world; in 2023, the brand decamped to Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro

Where: São Paulo

When: 1951

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Having been in Brazil scarcely five years, Bo Bardi’s first major project was a residence for her and her husband, writer and gallerist Pietro Maria Bardi, whom she had followed from Italy after their marriage in 1945. It was built in 1951 on what had been a tea plantation in the once-rainforest-covered hills that surround São Paulo. The architect designed two thin slabs made from reinforced concrete to sit on the slenderest of steel, stilt-like pilotis. These two slabs, forming the floor and the ceiling, were cut into to create a courtyard and then enveloped by a curtain of glass windows, allowing the trees that were planted by Bo Bardi to grow within and around, interacting with the architecture.

The Casa de Vidro or ‘Glass House’ she created was one of the first three residences to be built in the Morumbi area, a neighbourhood that would become a byword for a very Brazilian (and a very exclusive) modernist suburb: set in tropical nature and exuding a deceptive simplicity. The stunning use of glass and the open plan of the house’s layout allows the natural, external landscape to transmute inside, intermarrying with Bo Bardi and her husband’s carefully selected and very eclectic furniture, found objects and works of art.

This apparent simplicity belies an ingenious structural design that was drawn by Italian engineering master Luigi Nervi in 1950 and adapted by Túlio Stucchi in 1951. Bo Bardi’s architecture is so complete at the Casa de Vidro that it almost encapsulates her entire career, her attitude and even her legacy; it was her first attempt to find a Brazilian language for the Italian modernism she had been trained in. It was a very successful first attempt, too. This synthesis of Brazilian landscape and spirit with rationalist, European technique was the architect’s home for 40 years and now houses the Istituto Bardi. The Casa de Vidro is a crystalline distillation of her architectural philosophy.

MASP – São Paulo Museum of Modern Art

MASP was recently expended with a tower, seen to the left of the photograph

Where: São Paulo Museum of Modern Art

When: 1957-1968

The realisation of MASP is remarkable in more ways than one. The fact that Lina Bo and Pietro Maria Bardi, the glamorous new arrivals to Brazil from wartorn Italy, managed to accrue the leverage and influence to get this great modern museum off the ground is a great story in itself. It all began in 1947 when Pietro Maria befriended Assis Chateaubriand, a media magnate and famously controversial figure, helping him amass a vast collection of art which included works by Bosch, Mantegna, Titian and Goya. Pietro Maria took charge to become the museum's first director, and Bo Bardi would design a building fit for Chateaubriand's big ambitions.

Her concept was radical: the museum’s main volume hovers in mid-air, suspended between two colossal concrete beams supported by four pillars, which were then painted a crimson hue that subsequently became like an urban trope for São Paulo. The void beneath creates a public plaza and viewing deck, where a fussy, Belle Époque belvedere once stood. It was a democratic space in the heart of the megalopolis. At the time of construction, it was the largest free-standing span in the world.

A post shared by Stephanie Poon 潘芷慇 (@stephaniecypoon)

A photo posted by on

Inside, Bo Bardi’s transparent 'crystal easels' displayed artworks without walls, allowing visitors to move freely and break from traditional museum hierarchies. While finding a wonderfully innovative way to display Chateaubriand’s collection of European masters, for MASP’s opening show in 1969, Bo Bardi also curated an exhibition of objects from the Brazilian hinterland entitled 'The Hand of the Brazilian People', challenging perceptions of art. Yet more remarkable is that this all took place despite the military dictatorship that was installed in 1964. Lina’s MASP was a bold act of architectural resistance, and in the process, she created the definitive São Paulo landmark. One that was open, accessible, and unflinchingly modern; a poetic brutalism rooted in social purpose.

Solar do Unhão

Where: Salvador

When: 1959-63

In Salvador da Bahia, Bo Bardi embraced history, treating it not as a barrier but as a canvas. Beginning in 1959, she transformed the colonial-era Solar do Unhão, a crumbling 17th-century sugar mill and residence overlooking the bay that gives Brazil's old, colonial capital its name. Bo Bardi's interventions were delicate yet radical: rather than erase the ruins, she made them a stage for contemporary art and community life, weaving modern architecture into weathered walls and courtyards. Her philosophy of ‘knowing how to live in the ruins’ honoured memory while inviting renewal, argues Brazilian writer and curator Luiza Proença.

Her commitment to Salvador’s cultural fabric extended beyond Solar do Unhão to projects like the Barroquinha Cultural Centre, Casa do Benin, and the historic Ladeira da Misericórdia – a steep street embodying the city’s layered identities. Here, she created a modernist grotto built into the ruins and natural landscape. Bo Bardi’s profound connection to Bahia’s heritage features prominently in Sir Isaac Julien’s 2019 film, Lina Bo Bardi – A Marvellous Entanglement, which explores the entwined histories of place, art, and identity.

SESC Pompéia

Where: São Paulo

When: 1977-1986

In the post-industrial neighbourhood of Pompéia, at a former factory complex, Bo Bardi created a new kind of public architecture, one that Brazil had never before seen: one that was open, adaptable, and deeply human. Commissioned by the progressive social service institution SESC (a very Brazilian peculiarity that has few global equivalents) in the late 1970s, the project transformed the site into a cultural and leisure centre serving the local working and middle-class community.

Rather than erase the industrial past, Bo Bardi embraced it. She preserved the original concrete sheds, inserting libraries, theatres, workshops, and cafés into their raw, robust shells. She designed a meandering indoor stream, whose water trickles over polished stones, referencing Japanese gardens. She built three striking towers of exposed concrete, linked by aerial walkways that seem to float between the silo-like edifices. These contained gymnasiums, changing rooms, and social spaces – all sculpted with playfulness and purpose. For Bo Bardi, this was not just architecture but activism. SESC Pompéia was a 'citadel of freedom' – a place where culture, sport, and everyday life could mix. Decades on, it remains a radical model of inclusive, democratic design.

Teatro Oficina

Where: São Paulo

When: 1984

In her renovation of Teatro Oficina, Bo Bardi turned a burned-out office building on a scrappy plot of land into a space of radical expression. Working with stage actor, director and playwright José Celso Martinez Corrêa (known as Zé Celso), she stripped the building back to its bones and reimagined it as a narrow, high-volume performance arena, part stage, part street, part ritualistic procession. Instead of a traditional proscenium, Bo Bardi inserted a long central runway flanked by steep scaffolding bleachers, allowing actors and audience to share the same raw energy. The roof was partially opened to let in sun and rain, reinforcing the sense that the theatre was alive, porous, and unfinished.

This was theatre as revolution: physical, political, unpredictable. Bo Bardi’s interventions respected the spirit of the space while intensifying its immediacy. Teatro Oficina remains one of her most visceral works, a living monument to Brazilian counterculture and to her enduring belief that architecture should provoke, liberate, and engage. In recent decades, plans for high-rise developments on adjacent land have sparked fierce controversy, seen by many as a direct threat to the theatre’s radical openness and cultural legacy.

Casa Valéria P Cirell

A post shared by SIDE GALLERY (@side.gallery)

A photo posted by on

Where: Morumbi, São Paulo

When: 1958

Designed in 1958 for the architect’s friend Valéria P Cirell, the home appears almost hand-sculpted – a rough, geometric form clad in stone, pebbles, and ceramic shards, more organic ruin than polished modernist villa. In contrast to the steel and glass of her earlier Casa de Vidro nearby, this house embraces earthiness and enclosure. Vegetation threads through the walls and up onto green roof terraces that harvest rain and cool the interiors. Inside, two bedrooms, a spartan spiral stair, and a mezzanine are arranged around generous shared spaces that open fully onto the garden and swimming pool. The house, like the neighbourhood of Morumbi in general (that Bo Bardi was so pivotal in defining) is a private sanctuary in the middle of the city. Influenced by Antoni Gaudí and the Iberian roots of Brazilian culture, the house reveals another side of Bo Bardi’s architecture: more tactile, more rooted, but still definitely modern. A hidden gem, it remains one of her most poetic and personal works.

David is a writer and podcaster working (not exclusively) in the fields of architecture and design. He has contributed to Wallpaper since 2022 when he wrote about the late, postmodernist architect and founder of the Venice Architecture Biennale - Paolo Portoghesi reporting from his home outside Rome. In 2024, David launched Arganto - Gabriele Devecchi Between Art & Design, a podcast exploring the life and legacy of this Milanese silversmith and design polymath.

-

Wallpaper* Design Awards: cult London fashion store Jake’s is our ‘Best Retail Therapy’

Wallpaper* Design Awards: cult London fashion store Jake’s is our ‘Best Retail Therapy’Founded by Jake Burt, one half of London-based fashion label Stefan Cooke, the buzzy, fast-changing store takes inspiration from Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas’ 1993 The Shop and Tokyo’s niche fashion stores

-

Behind the scenes of OK Go's Grammy-nominated vinyl packaging

Behind the scenes of OK Go's Grammy-nominated vinyl packagingIndie-rock group OK Go have returned with an innovative new sound and look for their fifth album. We meet singer Damian Kulash to find out more.

-

A new venture led by will.i.am, Trinity is an electric, AI-powered ‘brain on wheels’

A new venture led by will.i.am, Trinity is an electric, AI-powered ‘brain on wheels’The tilting Trinity 3-wheeler EV has emerged from a partnership between Nvidia, West Coast Customs, inventor Dean Kamen and tech-enthused musician and cultural entrepreneur will.i.am

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthFrom wineries-turned-music studios to fire-resistant holiday homes, these are the properties that have most impressed the Wallpaper* editors this month

-

A spectacular new Brazilian house in Triângulo Mineiro revels in the luxury of space

A spectacular new Brazilian house in Triângulo Mineiro revels in the luxury of spaceCasa Muxarabi takes its name from the lattice walls that create ever-changing patterns of light across its generously scaled interiors

-

An exclusive look at Francis Kéré’s new library in Rio de Janeiro, the architect’s first project in South America

An exclusive look at Francis Kéré’s new library in Rio de Janeiro, the architect’s first project in South AmericaBiblioteca dos Saberes (The House of Wisdom) by Kéré Architecture is inspired by the 'tree of knowledge', and acts as a meeting point for different communities

-

A Brasília apartment harnesses the power of optical illusion

A Brasília apartment harnesses the power of optical illusionCoDa Arquitetura’s Moiré apartment in the Brazilian capital uses smart materials to create visual contrast and an artful welcome

-

This modernist home, designed by a disciple of Le Corbusier, is on the market

This modernist home, designed by a disciple of Le Corbusier, is on the marketAndré Wogenscky was a long-time collaborator and chief assistant of Le Corbusier; he built this home, a case study for post-war modernism, in 1957

-

Inspired by farmhouses, a Cunha residence unites cosy charm with contemporary Brazilian living

Inspired by farmhouses, a Cunha residence unites cosy charm with contemporary Brazilian livingWhen designing this home in Cunha, upstate São Paulo, architect Roberto Brotero wanted the structure to become 'part of the mountains, without disappearing into them'

-

Louis Kahn, the modernist architect and the man behind the myth

Louis Kahn, the modernist architect and the man behind the mythWe chart the life and work of Louis Kahn, one of the 20th century’s most prominent modernists and a revered professional; yet his personal life meant he was also an architectural enigma

-

Arts institution Pivô breathes new life into neglected Lina Bo Bardi building in Bahia

Arts institution Pivô breathes new life into neglected Lina Bo Bardi building in BahiaNon-profit cultural institution Pivô is reactivating a Lina Bo Bardi landmark in Salvador da Bahia in a bid to foster artistic dialogue and community engagement