Engineer, philosopher, roboticist: inside the fine-tuned mind of Conrad Shawcross

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

From halcyon days spent in the London Science Museum's maths gallery, to under the hood of his first Leyland Sherpa van, we're about to journey deep into the mind of Conrad Shawcross. The London-based artist is the subject of Pyschogeometries, a new book published by his gallery, Victoria Miro, and arts magazine Elephant, that investigates his practice photographically, illustratively, and through a series of writings. It’s the first book of its kind that goes into such edifying detail about the artist's work to date.

What strikes you immediately when reading it: Shawcross' practice is remarkably complex. Hang from every word as he jumps from reference to reference, from the philosophy of science, to childrens' toys, Greek mythology, Renaissance architecture and Buckminster Fuller. Keep up if you can. His sculptures may appear, on one level, like ‘childlike stacks of blocks' (his words), but there's incredible allusion, architecture and abstraction here – and that's what this book focuses on.

‘This is conceptual art that somehow also hits us in the preconscious, connects us with our most elemental wirings,’ Wallpaper* senior editor Nick Compton writes in the introductory essay, capturing the essence of the book’s title. ‘Pyschogeometries’, a theory coined by Italian physician Maria Montessori (1870-1952), suggests that being introduced to geometries at the earliest stages of development can fire up crucial neural connections and aid learning and insight – in all areas – throughout our lives. Geometry is, she suggests, ‘a gymnasium for the mind’, a way to stretch our intelligence abstractly, before we have the life materials to do it for real.

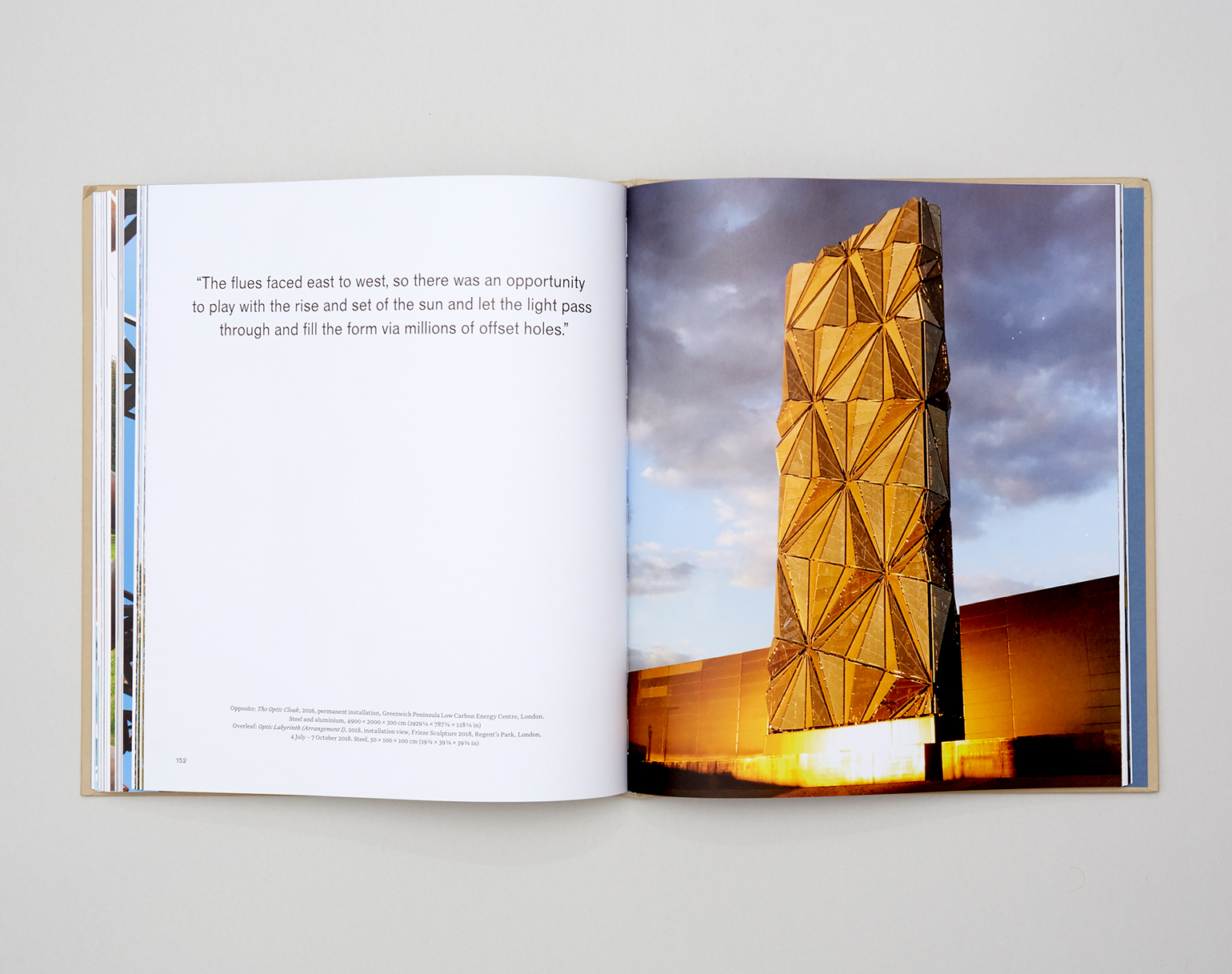

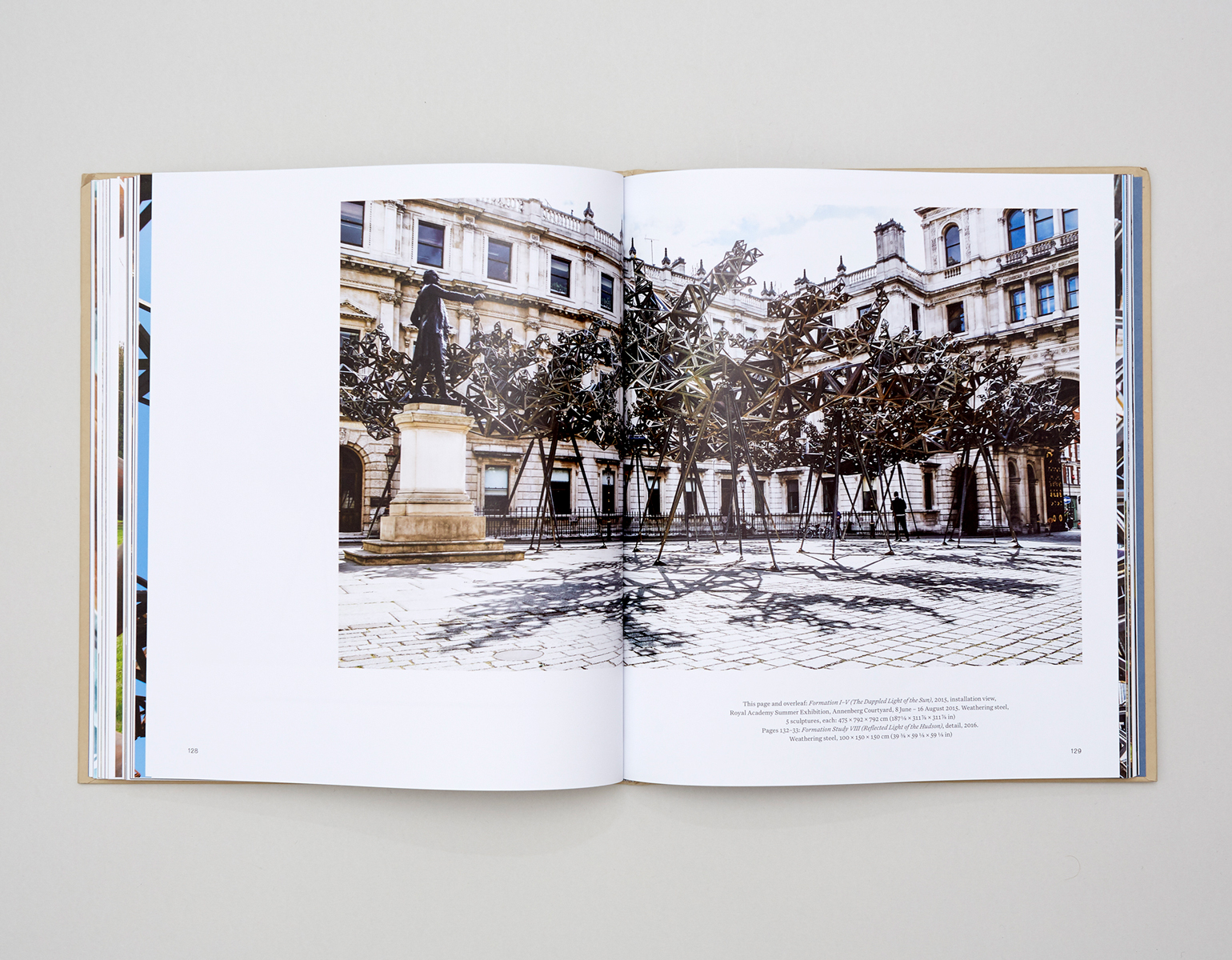

Shawcross stretches his psychogeoemtrical instincts across tetrahedral systems – a motif that recurs throughout his work, in Formation (2015), Paradigm (2016), in the Optic Cloak tower in Greenwich (2016), and in the recent Fractures sculptures (2018). In the book, Shawcross explains how he is interested in the tetrahedron mathematically, but also because of what it represents. The tetrahedron lies at the basis of nature, most obviously in H2O at molecular level, and in DNA, which comprises molecular variants of what Buckminster Fuller called the ‘tetrahelix’. These towering, brink-of-collapse, ‘whisp of smoke' sculptures represent nature, and humanity, at its most elemental.

Shawcross is also preoccupied with machinery. His early work, in particular, revolves around mechanically complex engine-making. Recall the giant, intricate rope production works, Yarn, (2001), The Nervous Systems (2003) and Chord (2009) that spooled colourful threads across London institutions when the artist was still in his twenties. ‘There is (self-consciously) something of the Victorian Gentleman scientist about Shawcross, the untethered engineer, physicist and metaphysicist,' Compton writes of the artist's fascination with nuts, bolts, cogs and axles. ‘He'd make a great Frankenstein.'

RELATED STORY

Frankenstein, maybe. Roboticist, for sure. With AI on the rise in the 2010s, Shawcross’ interest in mechanics moved into robotics. ‘I came across a five-axis robot in an art fabrication studio and it kind of stopped me in my tracks,' he explains of his first interaction with artificial intelligence, linking it to artistic progression. For Shawcross, coding is a kind of choreography – quite literally in the case of his 2012 collaboration with Wayne McGregor and Kim Brandstrup at the Royal Opera House, where he hard-coded a relentless robotic arm (‘Diana’) to dance alongside Royal Ballet’s best – Carlos Acosta, Leanne Benjamin, Tamara Rojo and Ed Watson, in swinging, pulsating time to the score.

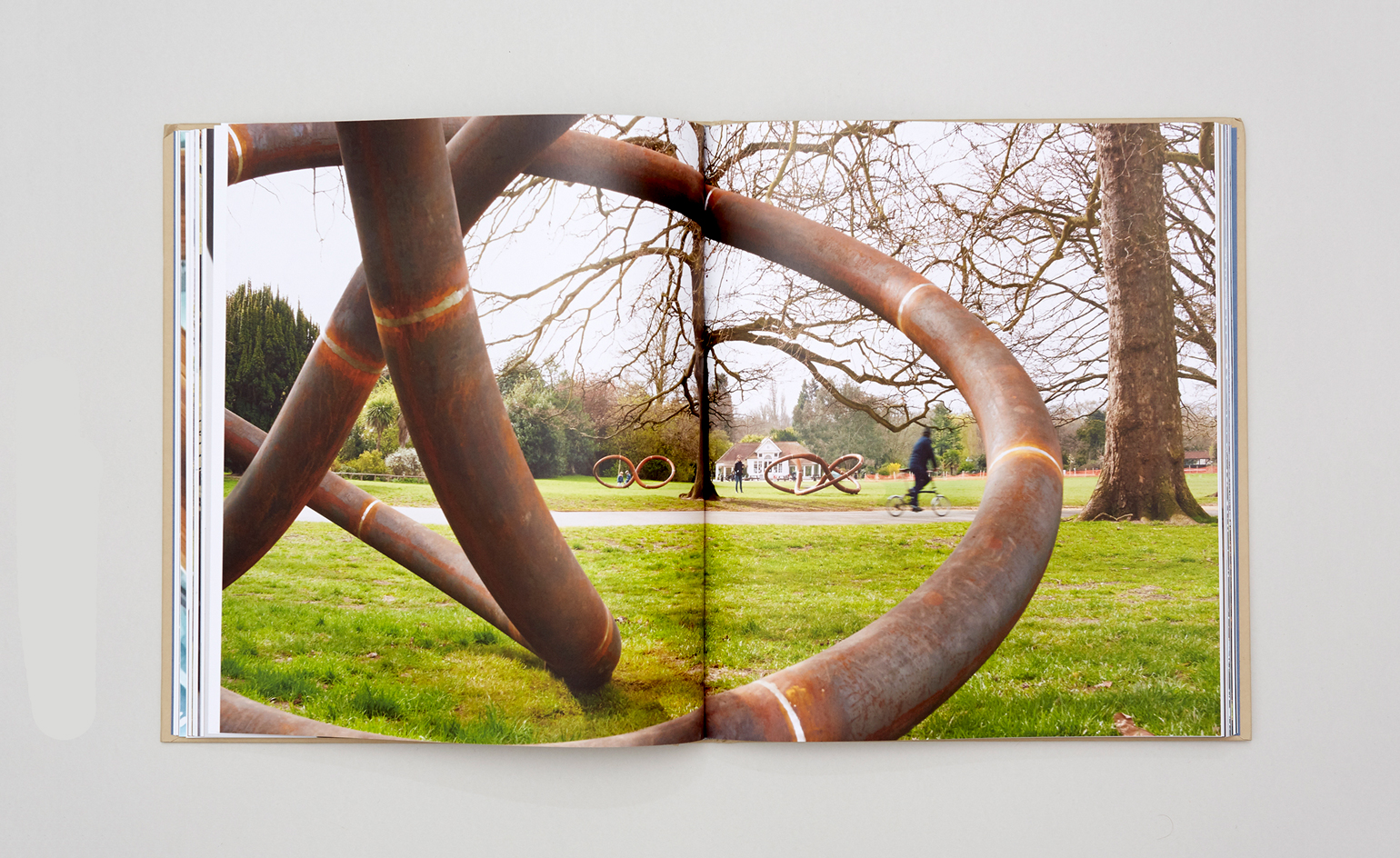

Through all this talk of geometries, mechanics, robotics, and what the artist calls ‘audacious structural forms’, it might be all too easy to assume that Shawcross’ work lacks sensitivity, or emotion. But this is to miss his musicality, flowing contours, rhythms, references, histories. The poetics of his work is heard most clearly in the chapter called ‘Harmonics’, which focuses on Shawcross’ attempts to transmogrify sensory experiences of music into a visual medium. The pages are lined with intricate drawings, made by pendulum driven pencils; works in lighting design that dance across the page; looping sculptures that make cast iron appear weightless.

‘I like the idea of [the works] appearing at first to be a piece of industrial infrastructure in the urban realm, feeling quite austere and like functional utilitarian objects,' Shawcross writes in the book. ‘But then on closer examination, once you enter into them, you suddenly find yourself in something that beneath the cloak is more poetic, more ethereal.’ That is, in a sense, what the book allows us to do – intimately step within the works, look deep into their geometric or mechanical structuring, perceiving it how the artist himself does; poetically.

The Optic Cloak, 2016. Permament installation, Greenwich Peninsula Low Carbon Energy Centre, London

Formation I-V (The Dappled Light of the Sun), 2015. Installation view, Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, Annenberg Courtyard (8 June - 18 August 2015)

‘Inverted Spires and Descendent Folds’, installation view, Victoria Miro Gallery II, London (10 June - 31 July 2015)

INFORMATION

Conrad Shawcross: Psychogeometries, £35, published by Victoria Miro and Elephant. For more information, visit Conrad Shawcross’ website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Elly Parsons is the Digital Editor of Wallpaper*, where she oversees Wallpaper.com and its social platforms. She has been with the brand since 2015 in various roles, spending time as digital writer – specialising in art, technology and contemporary culture – and as deputy digital editor. She was shortlisted for a PPA Award in 2017, has written extensively for many publications, and has contributed to three books. She is a guest lecturer in digital journalism at Goldsmiths University, London, where she also holds a masters degree in creative writing. Now, her main areas of expertise include content strategy, audience engagement, and social media.