‘The Barbican Estate’ by Stefi Orazi celebrates 50 years of modernist living

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

London’s Barbican Estate is revealed through a social lens by writer Stefi Orazi and photographer Christoffer Rudquist on the advent of the 50-year anniversary of when residents first arrived. Uncovering all the eccentricities of living inside a modernist experiment, The Barbican Estate tells a story that travels between interior design and daily life through essays, residents’ experiences and photography.

The layered Barbican complex, placed on a piece of land that writer John Allan describes in his essay for the book as essentially a ‘tabula rasa’ created by aerial bombardment, was designed by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon and took over 30 years to complete. The residential machine, made up of 2000 apartments, gardens, water and the Barbican arts centre, has been extensively dissected by architectural enthusiasts over the years, yet, what of the people, asks Orazi, an 18-year resident of Barbican and the neighbouring Golden Lane Estate.

The Barbican Estate designed by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon features gardens, water and the Barbican Art Centre.

Exploring behind columns, front doors, communal corridors, down rubbish chutes, up to the highest balconies and into the smallest of bathroom sinks, with her study, Orazi sought to discover the human stories of the estate – and the social changes that have taken place over it’s five decade lifetime.

Orazi speaks to an array of characters; the onsite laundrette manager who started in 1999; a nine-year-old resident since 2008 who finds hedgehogs in the communal gardens and cripes about the surrounding cranes; a car park attendant who works on site and whose job triples up as concierge, security and postman. One canny former resident took advantage of the right-to-buy scheme, purchasing a flat for £40,000 and selling it in 1987 for over three times as much. The stories are revealing in many ways.

Charles Holland’s standout essay explains how the Barbican was pitched at professional residents of the middle classes – a modern equivalent to typologies such as London’s Georgian squares or Haussmann’s Paris, unlike Golden Lane, also designed by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon that was pitched as social housing. Holland writes that the Barbican belonged as much to the ‘emerging post-war culture of consumerism and leisure as it did to the social democratic ambitions of modernist architecture’.

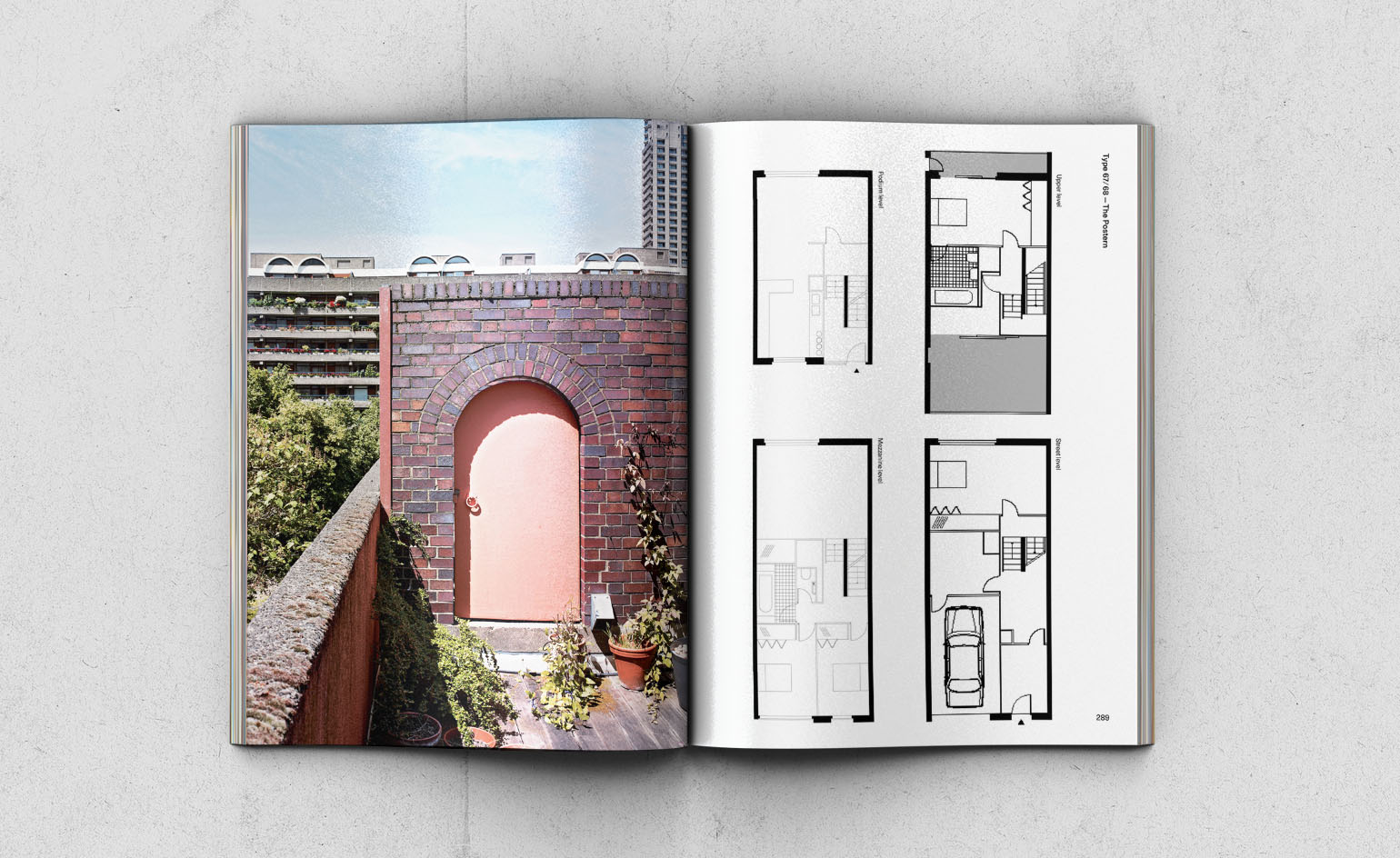

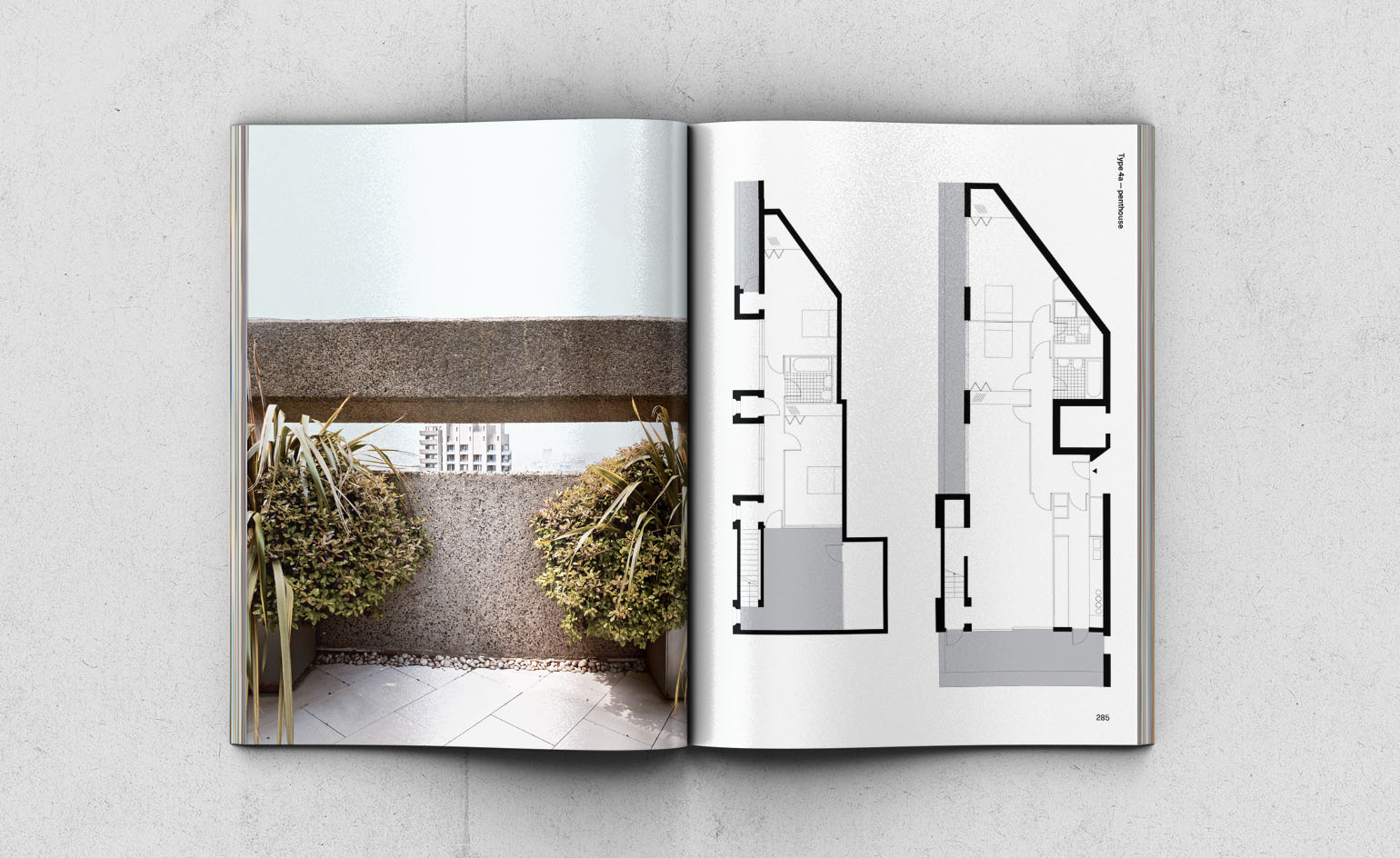

‘The Barbican Estate’ features photography and apartment plans side by side

The 140 different variations of flat types are an example of the Barbican’s aspiration for a set of distinguished residents – that Holland comically describes as an ‘almost Byzantine level of spatial variation’. The book lays architectural plans to pore over beside photography of the flat types, and recounts the unique characteristics of each of the 20 different blocks at the back of the book.

The bespoke interiors were all symbols of a modern, yet convenience-driven vision – the prefabricated kitchens, the compact ‘Barbican sink’ and the ‘Garchey’ a unique waste disposal system – which a current resident describes as a ‘big cauldron in your sink with a cylinder in the middle of it where you throw all your rubbish’ – prefaced by ‘The blasted Garchey!’

Yet even despite its age, today, the Garchey has gained a certain appreciation, a tenderness coupled with mysticism, similar to the status of a cassette or a rotary dial telephone. A signal that the Barbican has entered a phase of fetishisation – brutalism was back, a status symbol of pop culture, idealism and avant garde. And, there’s a market for it.

Holland describes a room tucked below the cinema complex, where they where they fix and trade original parts as an ‘unofficial salvage operation that reflects an interest and enthusiasm for authentic refurbishments by residents, ones where original door handles, locks and other details are reincorporated into flats that have previously been modified.’

‘This fetish for originality forms part of the Barbican’s canonical status as architecture and an icon of brutalism,’ writes Holland.

A bedroom with a window and balcony overlooking the estate.

Orazi’s own wide-eyed fascination began with her first visit to then Wallpaper* art director, Tony Chambers’ home: ‘We got into the lift, up to the sixth floor and into his (Type 36) apartment and I was speechless. A huge double-height living space, walls painted in Corbusian bright colours, simply furnished, books everywhere, wooden open-tread stairs – it was stunning.’

Throughout her experience of the Barbican, Orazi had slowly witnessed the demographic of the residents changing – from the average city worker in search of easy walk to the City, the building began to become occupied by the design-conscious – architects, designers and artists – often with young families.

The social and visual history of the book brings us up to today, here in London, where we are in the midst of a social and lower income-housing crisis. The Barbican is a valuable case study of architectural successes and weaknesses, yet it is equally reflective of human nature too and reminds us that we are all somewhat at peril to ourselves.

Statistics, population percentages and budgets can’t predict the birth of an icon, the festering of a fetish, the status of a symbol, the tempering of taste – or the cultivating of a community, the appreciation of a colossal concrete stack, and most surprisingly, the tenderness towards a modernist rubbish chute. This book reminds us, and delights us, that we – people, designers, architects and policy makers – can learn a lot from ourselves.

INFORMATION

‘The Barbican Estate’, Batsford, £40. For more information, visit the Pavilion Books website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.