The inimitable Norman Foster: our guide to the visionary architect, shaping the future

Norman Foster has shaped today's London and global architecture like no other in his field; explore his work through our ultimate guide to this most impactful contemporary architect

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Lord Norman Foster has made more of an impact on London than any other architect since Sir Christopher Wren. From the Wembley arch and the Gherkin to the pedestrianisation of Trafalgar Square and the Millennium Bridge via the Great Court of the British Museum, his work is almost inescapable. His own practice’s office, on the banks of the Thames at Battersea, is also one of the finest buildings in the city, a sleek glass block, exquisitely detailed and shimmering with the rippling river outside. And it was recently announced that he has won the commission for the Queen Elizabeth Memorial in St James’s Park with its glitzy glass bridge. Yet Foster wasn’t born in London, and he doesn’t live here. The capital is just the tip of the Foster empire iceberg.

Who is Norman Foster?

Norman Foster was born in Stockport in 1935, old enough to remember the war, his father worked in the nearby Vickers factory. He started working as a clerk in the vast Gothic Town Hall, designed by Alfred Waterhouse. This Victorian behemoth, unfashionable as it might then have been, inspired the young Foster to study architecture. He paid his way by working as, among other things, a baker, bouncer and ice-cream man, that rare thing, a working-class, self-made architect. Having studied at Yale in the 1960s, he set up practice with his friend Richard Rogers and their partners Wendy Cheesman and Su Rogers, building a handful of small projects, including the striking Creek Vean (1966).

Creek Vean house in 2006

Norman Foster's early career

He went solo in 1967, struggling at first but still producing fine buildings, including the sinuous, cool and still-underrated Willis Faber Dumas Building in Ipswich in 1974 and a radically democratic dockside terminal in Millwall for shipping line Fred Olsen. It was the commission for HSBC’s Hong Kong HQ (completed 1985), which made his name.

HSBC Main Building (1985), Hong Kong

It was then the most expensive building in the world, A High-Tech tour-de-force of trusses, double columns and cranes and astonishingly clear floor areas spanning between. It was the corporate riposte to his old partner Richard Rogers’ Centre Pompidou (designed with Renzo Piano), ushering in a new age of financialisation and hyper-capitalism. Yet this corporate monster also provides shelter beneath, a place to picnic and even protest. It is typically Foster in its mix of spectacle and effect, private capital and public luxury.

Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts (1978), Norwich, UK, Foster's first public building, recently celebrated its 40th anniversary

Always inspired by the space-age comics of his childhood, by the Meccano he played with, by the industrial structures of Manchester, and by the planes he so loves (he famously pilots himself), Foster told me once, ‘I always had this idea that the future will be better than the past.’ Certainly, his future kept getting better.

HSBC imparted a global reputation, and he knew what to do with it. He remade Bilbao’s metro system, the presence of the stations marked by glass cowls that became known as ‘Fosteritos’ (Frank Gehry credited these as the real Bilbao effect), he built a sleek airport of exquisite clarity at Stansted (now mostly ruined by commercialism, security and expansion) and would later design the world’s biggest airport in Beijing, now itself being overtaken by King Salman International Airport in Riyadh, also, of course, designed by Foster.

Reichstag, New German Parliament (1999), Berlin, Germany

After the reunification of Germany, he was commissioned to redesign the burnt-out ruins of the Reichstag. He reimagined the dome as a spiralling, crystalline lighthouse, a gesture towards openness and hope, in which the public could climb and symbolically look down on their representatives. For an architect occasionally accused of a technocratic chilliness, it was a theatrical, deeply meaningful gesture that helped remake a nation.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Fosters' Château Margaux winery extension, completed in 2015

Norman Foster's impact today

Foster appears to lead a charmed life. At the age of 90, he still flies himself, cycles across mountain ranges and takes part in ski marathons. His Instagram page tells a story of a legend of lifestyle situated between appearances at the UN, in sleek sports cars, visiting skyscraper sites and at home sketching buildings (which are already mostly complete). But his career has not been as smooth as all this suggests. He went through a number of sparse periods, was criticised for situating himself in Switzerland as a tax exile and has taken flak for his buildings’ environmental impact, talking up a good sustainability game while designing vast airports and, more recently, space bases. His love of planes and cars, of rockets and spaceships, can make him look like a machine obsessive from another era.

Queen Elizabeth II national memorial

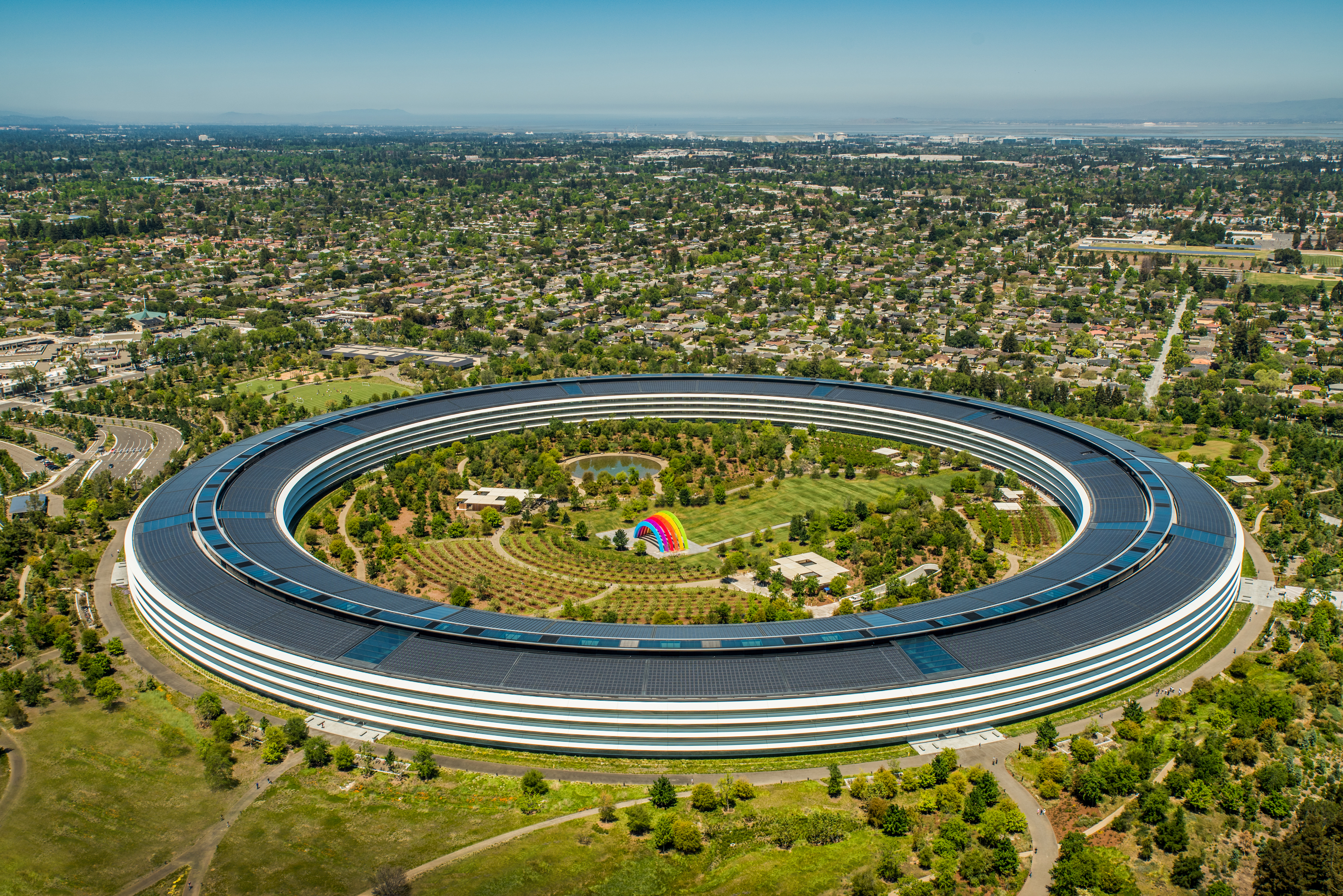

It’s barely possible to cover even Foster’s greatest buildings in an article of this length. From the Carre d’Art in Nimes which somehow manages to sit by a Roman temple and gently compete to the sublime Millau Viaduct; from the architectural equivalent of an iPhone, the Apple Park campus in Cupertino, to the wonderful Canary Wharf Station in London; he is not only arguably our age’s most successful architect but also, almost certainly, its most admired.

Norman Foster's 10 key projects & buildings

Willis Faber & Dumas Headquarters (1975), Ipswich, UK

One of Foster's earliest solo commissions after founding Foster Associates (which later became its current incarnation, Foster + Partners), this is the design for the country headquarters for insurance company Willis Faber & Dumas. Its defining feature is its sheath-like, glass curtain wall.

Carré d'Art (1993), Nîmes, France

One of Foster's best-known earlier works, the Carré d'Art is a cultural hotspot in the French city of Nimes. Facing the preserved Roman Temple across the street, Maison Carrée, this is a mediatheque, which means it brings together library functions with music, video and cinema.

Millennium Bridge (2000), London, UK

This steel suspension pedestrian bridge connects St Paul's with the Tate Modern and Southbank, offering a memorable daily commute to many and an unforgettable tourist route since it opened in 2000. While it closed only three days after its launch due to swaying, it reopened a couple of years and some engineering modifications later, and remains a key piece of infrastructure for the capital to this day.

Great Court, British Museum (2000), London, UK

The Great Court at the British Museum shelters over six million tourists annually. Originally a garden, when the period building was first launched in the 1800s, the space was repurposed at the turn of the century to become one of London's most iconic indoor publicly accessible spaces - a master plaza and circulation hall for one of the capital's biggest museums.

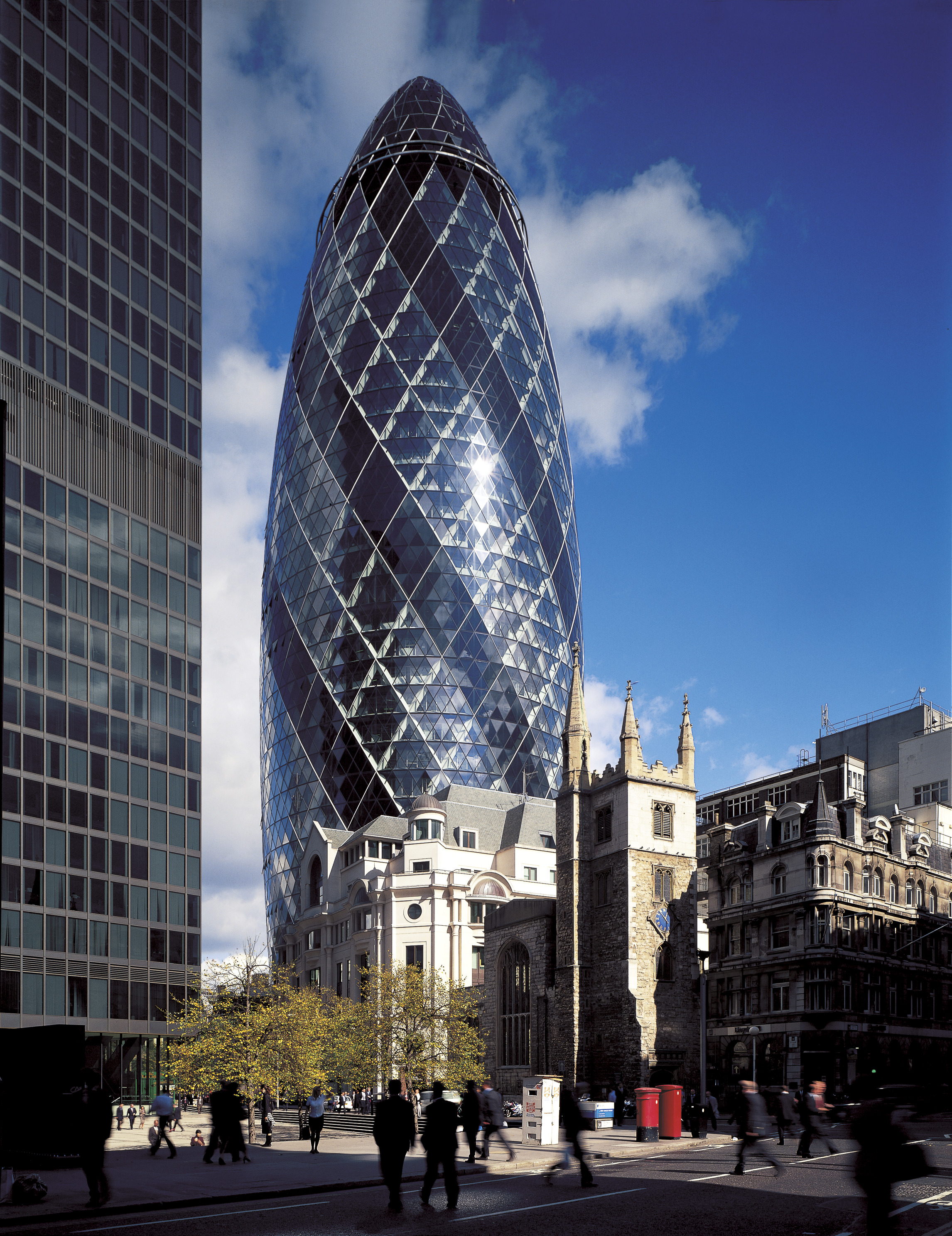

30 St Mary Axe (The Gherkin) (2004), London, UK

Known to most as The Gherkin, 30 St Mary Axe forever changed London's iconic skyline when it opened in 2006. Forty storeys high and across some 46,400 square metres of office space inside, this is a 21st century workspace, with a 360-degree panorama club room at the very top.

Hearst Tower (2006), New York City, USA

A new tower rising above an existing building which serves as its plinth, the Hearst Tower in New York is instantly recognisable for its triangulated 'diagrid' form. It is made of 85 per cent recycled steel, which, alongside other environmentally friendly gestures, means 'it consumes 25 per cent less energy than an equivalent office building,' the architecture studio explains.

Queen Alia International Airport (2013), Amman, Jordan

This international airport, the main gateway to Amman, is not only visually striking, seemingly crafted out of an arrangement of simple concrete domes echoing the veins of leaves; it is also designed with environmentally sensitive features such as its many courtyards which help filter the air and clear pollution.

Bloomberg London (2017), London, UK

This formidable office is the first Bloomberg building that has been custom-designed for the business. Set between Bank and St Paul's, the 3.2-acre site also returns a lost part of Watling Street back to the public realm, encompassing three public plazas and restoring a Roman temple beneath its sizeable mass. Its heavy, smoothly gridded facade of Derbyshire sandstone and bronze is certainly physically dominating, yet instead of attention seeking, it is mostly sturdy and reassuring.

Apple Park (2017), Cupertino, USA

Apple Park headquarters, included in the Norman Foster exhibition at Centre Pompidou in Paris in 223

Foster + Partners is behind Apple Park, the tech giant's home in Cupertino, USA. The design is created to embody California's spirit of openness, creativity and connection to nature. Its central building, The Ring, is placed among more structures for specific uses - an auditorium, exhibition areas and more - and all are set within flowing parkland.

Apple store at Battersea Power Station (2023), London, UK

The Apple store at Battersea Power Station in London was the first sighting outside the US of the tech giant’s new, or at least evolved, retail design as it relaunched in 2023. A re-engineering rather than a radical facelift, the store's design prioritises sustainability and applies, as much as possible, ‘universal design’ principles.

Edwin Heathcote is the Architecture and Design Critic of The Financial Times. He is the author of about a dozen books including, most recently 'On the Street: In-Between Architecture'. He is the founder of online design writing archive readingdesign.org and the Keeper of Meaning at The Cosmic House.