What is Bauhaus? The 20th-century movement that defined what modern should look like

We explore Bauhaus and the 20th century architecture movement's strands, influence and different design expressions; welcome to our ultimate guide in honour of the genre's 100th anniversary this year

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

The cover of the 1919 Bauhaus Manifesto featured an expressionist woodcut of a Gothic cathedral with dazzling stars shooting beams from its towers. Drawn by Bauhaus founder architect Walter Gropius, the manifesto kicked off with the phrase ‘The ultimate goal of all art is the building.'

Yet the Bauhaus, which has come to represent more than anything a style of stripped, modernist, functional architecture, did not initially even have an architecture department. It is only one of a plethora of paradoxes about the most famous art school ever. The Bauhaus, we have to remember, was never just one thing.

Bauhaus building Dessau, architect Walter Gropius, southwest view, construction site photo, 1926

What is Bauhaus architecture?

Founded in the wake of the devastation of the First World War, which left Germany beaten, impoverished, shamed and traumatised, Bauhaus was intended as a new guild, based on a medieval model in which the crafts could be unified to serve a modern agenda. The cathedral on that cover represented the zenith of the western Gesamtkunstwerk (a 'total work of art' in German), a building that embodied symbolism and meaning, stonework, applied arts, geometry and collaboration.

Today, though, when we think of Bauhaus, we probably think of a particular style; the white villas of the 1920s and 30s, rigorous blocks of repetitive flats or the tubular chairs of Marcel Breuer and Mies van der Rohe. We might also think of all the things that the word ‘Bauhaus’ is applied to, the modernist apartment blocks of Stuttgart, Budapest, Bucharest or Tel Aviv.

A building in Tel Aviv's White City, where according to the World Monument Fund is 'one of the world's largest concentrations of Bauhaus architecture'

Bauhaus: its origins and scope

If the Bauhaus is known for control, perfection and modernist minimalism, its beginnings were surprisingly diverse and a little chaotic. There was the abstraction of artists Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, the pottery, ceramics and textiles of the women designers who were excluded from the art studios and furniture workshops, which were the preserve of males, and there was photography, metalwork, theatre and graphics and more. Its beginnings were steeped not in functionalism but in mysticism, in the cultish atmosphere of devotion, such as the monkish demeanour of painter and designer Johannes Itten with his occult leanings and adherence to the odd pseudo-religion of Mazdaznan (a movement aiming to elevate consciousness through body and spirit). It only slowly shed these more eclectic leanings as director Gropius pursued a more rigorous line towards modernist architecture and design.

Over the course of the 1920s, the school began to shift towards a more architectural approach and by the time Hannes Meyer and later Mies van der Rohe were in charge (1928-1933), architecture had become firmly established as its key legacy.

Construction workers in the shell of the workshop wing of the Bauhaus building in Dessau, 1926

Bauhaus manages to be both a badge of honour and an insult. To those who love it, it is the pinnacle of modernism; pure, clear, honest, revolutionary and functional. For others, it exemplifies the pretension, arrogance, inhumanity and fakery of modern architecture.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

In architecture, its features have become cliché yet still often look astonishingly modern. Take the Bauhaus building itself. Designed by Walter Gropius in Dessau (where the school had moved to from Weimar) in 1925-26, it was intended to look industrial; a factory of ideas and images as well as production. The glass curtain walls dematerialised its presence while creating light-filled interiors, another element appears as a bridge, seemingly floating over a central spine route, similarly light and airy.

Ribbon windows accentuate its horizontality, indicating the direction of travel within the building. On one wall, a grid of small balconies casts a photogenic pattern of shadows and appears almost like diving boards from which to launch into the future. Materials are concrete, steel and glass (at least, they are made to appear to be). It is a building which, a century after it was designed, still looks contemporary, and that is because the Bauhaus defined our idea of what modern should look like.

Bauhaus stage, Pantomime ‘Treppenwitz’ by Oskar Schlemmer on the roof of the studio building, 1927

We might also look at the Masters’ Houses (1925, Gropius again) designed for his colleagues, Marcel Breuer, Klee and Kandinsky. They are blocky, asymmetric and Constructivist, revelling in their composition as apparently abstract architectural sculptures which are actually meticulously designed to suit their purposes, expressing the volumes inside. They remain, in a way, the model for modernist villas, with roof decks, nautical railings and blocky, boxy forms. And, perhaps most of all, white walls. The white expressed a new purity of form, a departure from the grey tones of the dirty, polluted city into an idealised perfection, architecture as clean and full of potential as a crisp new sheet of paper.

The material was supposed to be concrete, that protean matter which could be moulded into any modern form. In fact, it was mostly brick, rendered with plaster to look modern. Concrete was still expensive and rare. Brick and block were cheap and ubiquitous. Here, we see something of the Bauhaus that was so often parodied, a willingness to sacrifice actual integrity for the appearance of integrity. Mies van der Rohe was also later parodied for sticking steel I-beams onto the outsides of his buildings because he’d had to cover up the real structural elements for fireproofing. For a movement steeped in ideas about morality, it was notably willing to compromise.

Just as the furniture, the bent steel tubes and glass were intended to appear mass-produced, fit for the mechanical age, but were actually made by craftsmen creating expensive handmade pieces. The architecture was about an idea of mass production aimed at a model of worker housing, but made by hand.

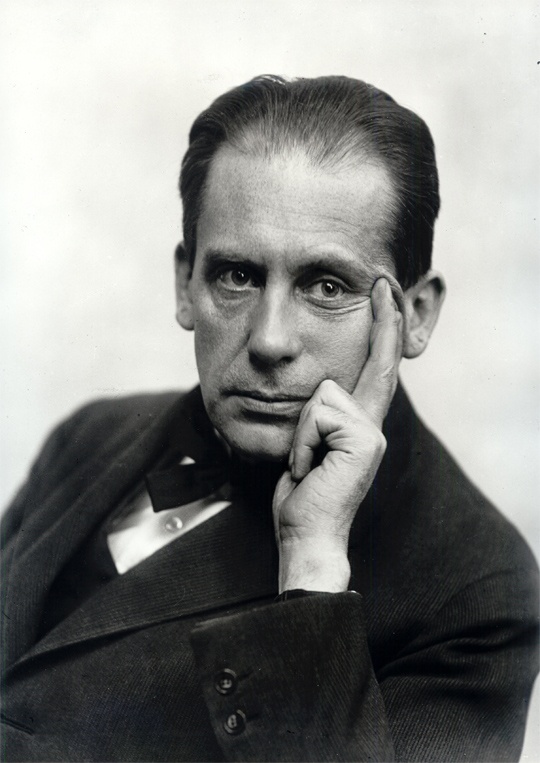

Architect Walter Gropius, the man behind the design of the Bauhaus Dessau school building

At the heart of the Bauhaus was an idea of design for all, of design as a force for social good the ultimate goal of which was the creation of a new, more equitable world of decent housing for the working classes, of green spaces and efficient buildings, well-lit, well-ventilated and fit for a new openness of everyday life. It posed the ending of compartmented, small, dark rooms for open plan spaces and balconies and roof terraces. It promoted communal dining rooms and facilities, a new way of living together with the Bauhaus school in Dessau as its model. It was socially deterministic in a manner that has become deeply unfashionable - the suggestion was that architects could mould society through their buildings to become better.

There were many experiments, most notably the Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart (1927) with its mass of model housing, white-walled blocks designed by architects from Mies van der Rohe to Le Corbusier to propose a new way of living in the green of the suburbs.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (design), Berliner Metallgewerbe Josef Müller (manufacture),Tubular steel stool, 1927

Bauhaus: an evolution

But the dreams never quite materialised. The aesthetic was taken up by the intellectual bourgeoisie while the proletariat remained suspicious. Most of the Bauhaus architects ended up working on middle-class villas in the suburban hills. Wander around the leafy suburbs of Budapest or Berlin, Brno or Bucharest, and you will find exquisite white-walled villas, often crumbling a little, the legacy of the fashion of Bauhaus style. The familiar elements coalesced into that very recognisable style. There were big picture windows and narrow strip windows. There was an attempt to break down the divisions between internal and external space, with terraces and balconies being treated as sun rooms. There were fluid interiors, rejecting compartmentalisation in favour of open plans. These were blocky white structures but also ones often augmented by curved corners or semi-circular balconies or towers - all based on the platonic geometries beloved of the Bauhaus founder, the back-to-basics set of building blocks.

There were oceanliner handrails (because what could be more functional than a ship?) and there were stripped-down fittings - from door handles to lights, often resembling industrial engineering more than domestic design. There were dramatic stairs in cylindrical towers or with open treads, or industrial steel spirals. The mouldings of traditional houses were banished along with fireplaces and sculptural plasterwork. Heavy furniture was disbanded in favour of tubular steel and glass, items which were almost transparent, that cast no dark shadows. Kitchens were built in and small, functional spaces which celebrated efficiency rather than conviviality. And there were no cellars or attics, only flat roofs - none of the dark repositories of memory or nostalgia.

The extent to which we can itemise these elements and archetypes is a little ironic, of course. Gropius and Mies were attempting to escape style, to drive at an objective, functional architecture, which was irrefutable in its practicality. Yet style it became.

Tom Wolfe, in his scathing book ‘From Bauhaus to Our House’ (1981), reflected on the appropriation of a worker-housing aesthetic applied to everything from schools to corporate offices. After the Second World War you might argue that it was Bauhaus architecture that inspired the explosion in social housing blocks set in green spaces which proliferated across the edges of cities around the world.

Illuminated workshop wing, Bauhaus building Dessau, 2021

What does Bauhaus mean today?

Now the word ‘Bauhaus’ has become ubiquitous and a little meaningless as a consequence. László Tóth, the fictional protagonist of 2024 film ‘The Brutalist’ was, of course, trained at the Bauhaus. It is a code so that we understand he was there at the source of modernism. Hungarians were indeed prominent there; there was Marcel Breuer and there was Farkas Molnár, who designed the first ever Bauhaus residence, the Red House of 1923, which was never built. And most of all, there was László Moholy-Nagy who ran the famous foundation course and set the tone, even if he wasn’t himself an architect.

Bauhaus (literally ‘house of building’) is just too good a word. There was a band named after it and a German DIY store. It is universally applied to apartment blocks in Tel Aviv, few of whose designers had anything to do with the Bauhaus, although they may have come from the same central European backgrounds. It is universally applied across Europe to refer to inter-war modernism of a certain type, just as Brutalism became the go-to description for anything post-war, concrete and sculptural.

Anni Albers, weaving - the artist's textile art was revived at Milan Design Week 2025 by Dedar with the Josef & Anni Albers Foundation

The Bauhaus itself lasted only till 1933, when the Nazis made it impossible to continue. By then, its director was Mies van der Rohe, who would later emigrate to the US and take his (rather more luxuriously minimal) version of the Bauhaus to Chicago, where it arguably had an even greater impact, not on worker housing but on corporate America.

Today, the idea of the Bauhaus has a tinge of asceticism, of a kind of functional puritanism. Yet a look at the photos of the school in everyday action reveals a world of parties and balls, of goofy photos and radical theatre. The school appears to be full of women, as it indeed was, and they look like they are enjoying themselves. Their efforts are now being reassessed with figures like Anni Albers, Marianne Brandt and Eva Zeisel being finally given their due, albeit outside architecture. It might be worth remembering that, as well as a legacy of austere houses and apartment blocks that look like factories, the Bauhaus was probably, against all expectations and reputations, also a lot of fun.

Examples of Bauhaus architecture

The Bauhaus Dessau, Germany, by Walter Gropius

Masters’ Houses, Dessau, Germany, by Walter Gropius

The Bauhaus Master House Kandinsky-Klee

Barcelona Pavilion, Spain, by Mies van der Rohe

Mies van der Rohe's Barcelona Pavilion celebrated 30 years in 2016

Doldertal Apartment Building, Zurich, Switzerland, by Marcel Breuer

ADGB Trade Union School, Bern, Berlin, by Hannes Meyer

ADGB Trade Union School

Dalnoki-Kovats villa, Budapest, Hungary, by Farkas Molnar

A post shared by sander patelski (@studiosanderpatelski)

A photo posted by on

2025 marks the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus School’s move from Weimar to its iconic home in Dessau, Germany, designed by Walter Gropius. To mark the occasion, a programme of exhibitions, conferences and festivals organised by the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation will take place in the city of Dessau from September 2025 to March 2026.

For more information visit bauhaus-dessau.de

Edwin Heathcote is the Architecture and Design Critic of The Financial Times. He is the author of about a dozen books including, most recently 'On the Street: In-Between Architecture'. He is the founder of online design writing archive readingdesign.org and the Keeper of Meaning at The Cosmic House.