Forces at play: SOM’s Bill Baker makes structural engineering fun

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

The question that Bill Baker, partner and chief engineer at SOM, asks himself when he travels to Shanghai, among other places, is: have we run out of good ideas?

On a mission to ensure that his team keeps asking questions and finding solutions, in whichever order, he initiated ‘SOM: Engineering x [Art + Architecture]’, a book and exhibition that present ideas and projects explored by the ‘Research Gang’ at SOM – an informal and voluntary group of engineers interested in pioneering new technologies with substance.

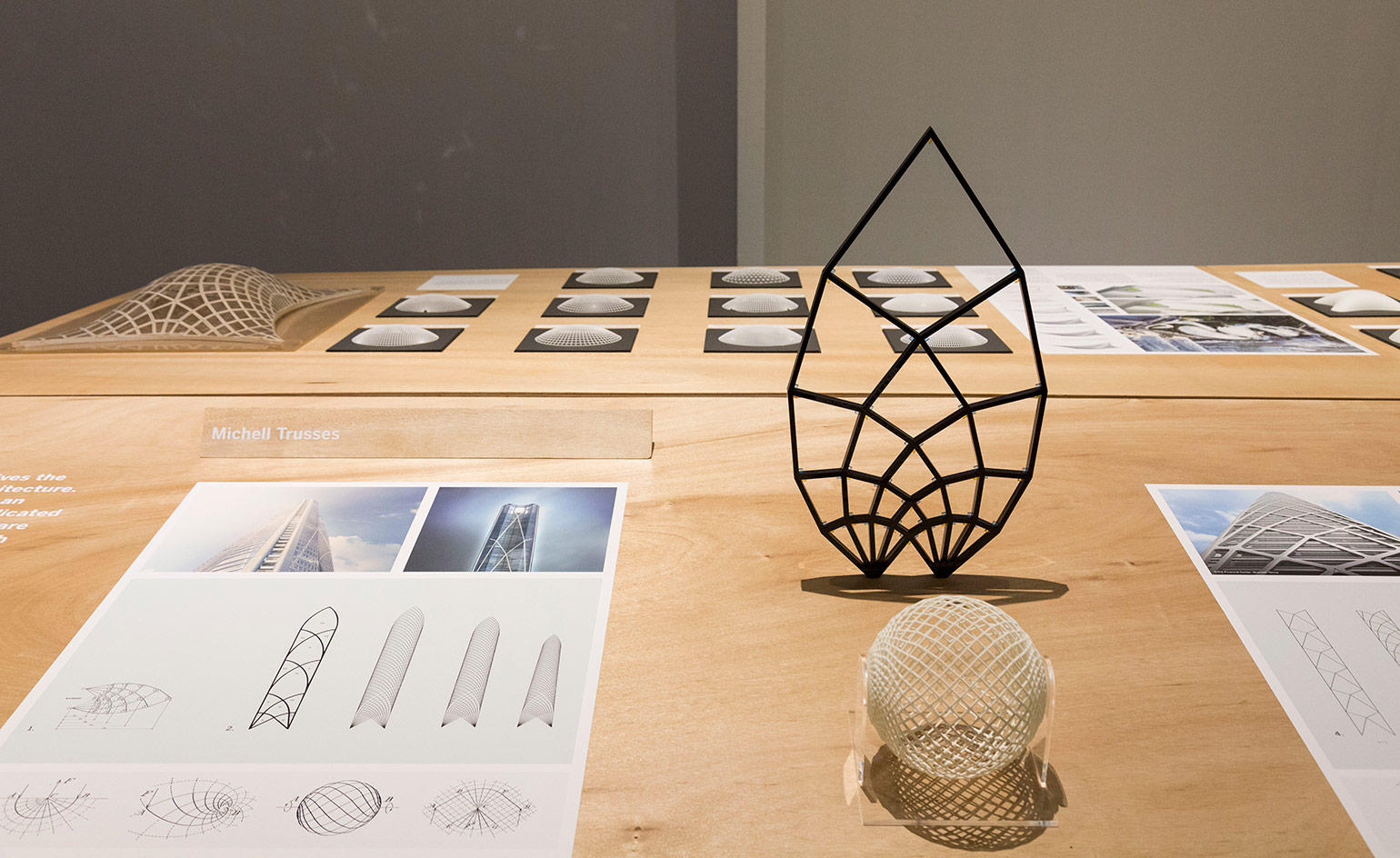

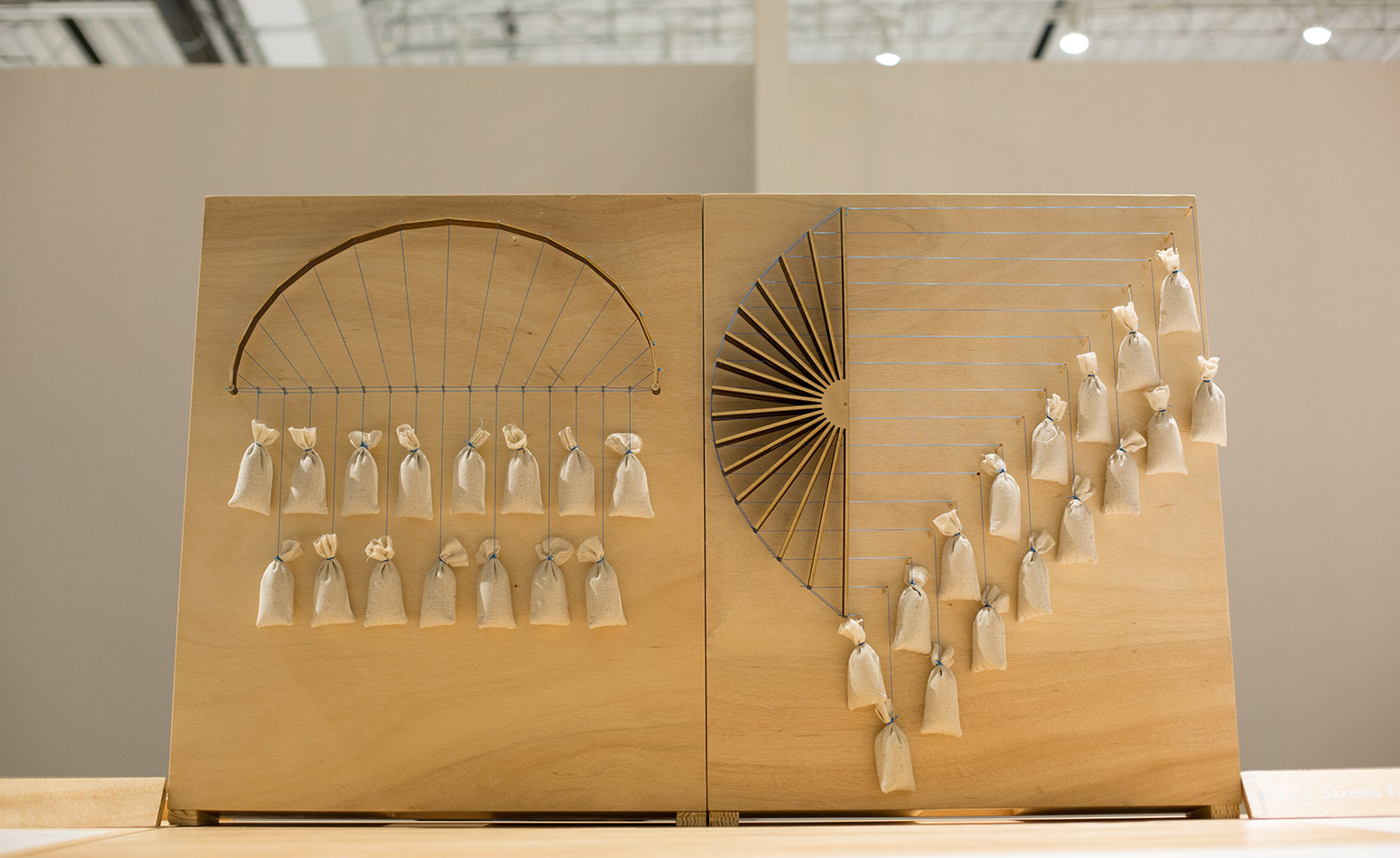

In Chicago, in collaboration with Mana Contemporary, SOM’s Research Gang has taken over a former paint warehouse. Archive tables host various structures, some familiar, others slightly odd-looking, from skewed lattice-shaped models to sculptures expressing torsion, a 3D printed hut, seismic impact testing devices and research into constructing tall timber buildings.

‘We’re doing all these giant buildings, but this kind of stuff gets us grounded again. The details matter,’ says Baker, who, with his colleague engineer Christian Hartz, joined Wallpaper* for a stroll around the exhibition.

Models on display at ‘SOM: Engineering x [Art + Architecture]’

.

‘A lot of these things are based on an infinite amount of numbers – how do you do things in a finite way? And how might it apply to tall buildings or trusses? All this stuff is not about solutions, its about ideas. You get an idea and it’s up to the design team to interpret the information.’

‘The exhibition helped us organise some of our thoughts and prioritise. We publish a lot of papers and sometimes they are too technical. The book helped us a lot to ask ourselves – what are we doing?’ says Baker who organised ‘SOM: Engineering x [Art + Architecture]’ in correspondence to the chapters in the book, and included the addition of a new chapter about engineering and art.

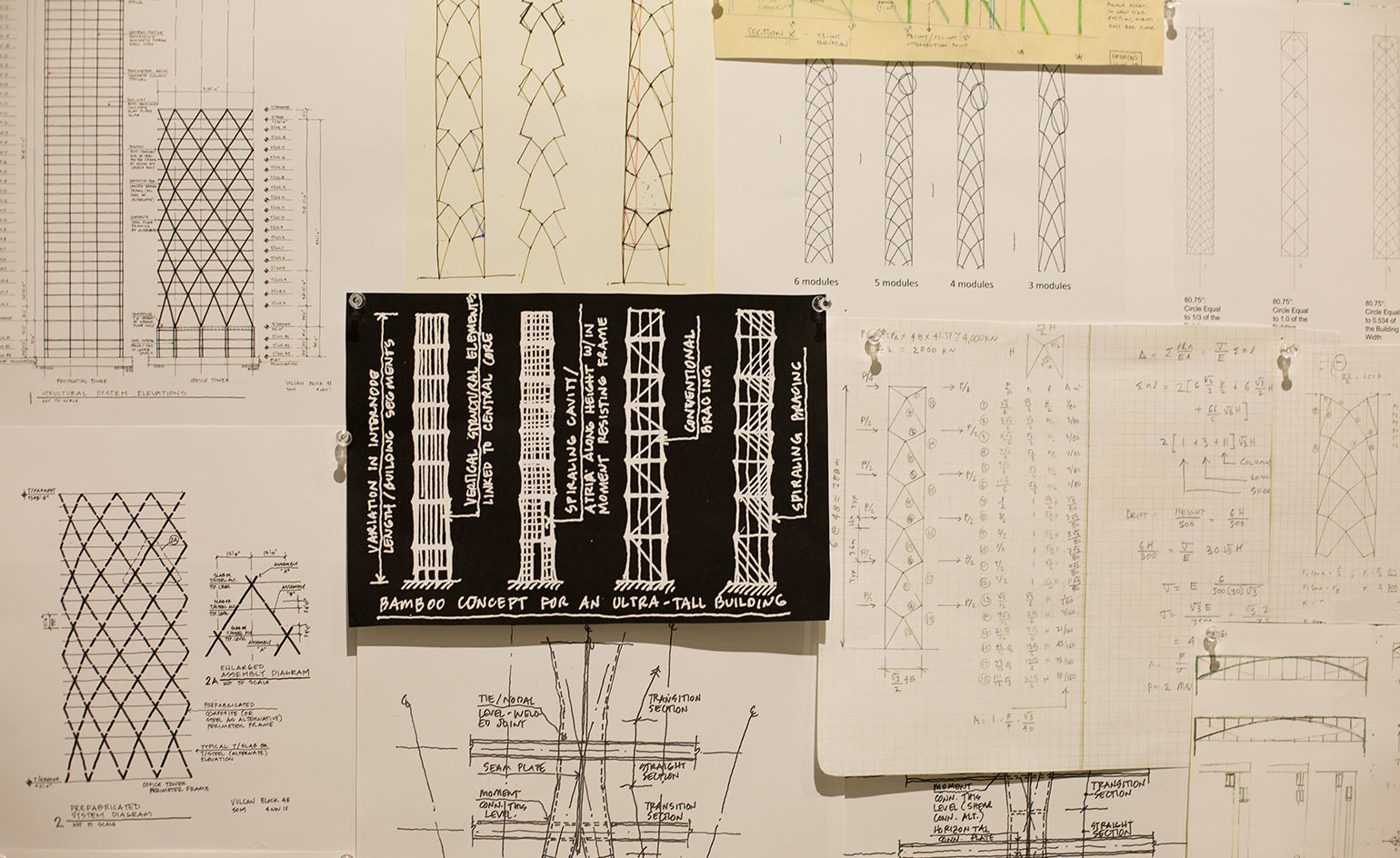

A pin board in the exhibition layered up with sketches, drawings and images is the Gang’s ‘idea wall’ – the architects and engineers at SOM have similar boards in their offices. ‘We all have sketchbooks and all the stuff we don’t know what to do with, the things that might be interesting in the future – you pin it up. Maybe it’s a solution for a question you don’t have. A lot of the time we’ll come up with a structural idea and stick it on the wall near the architects, leaving them a little subliminal message.’

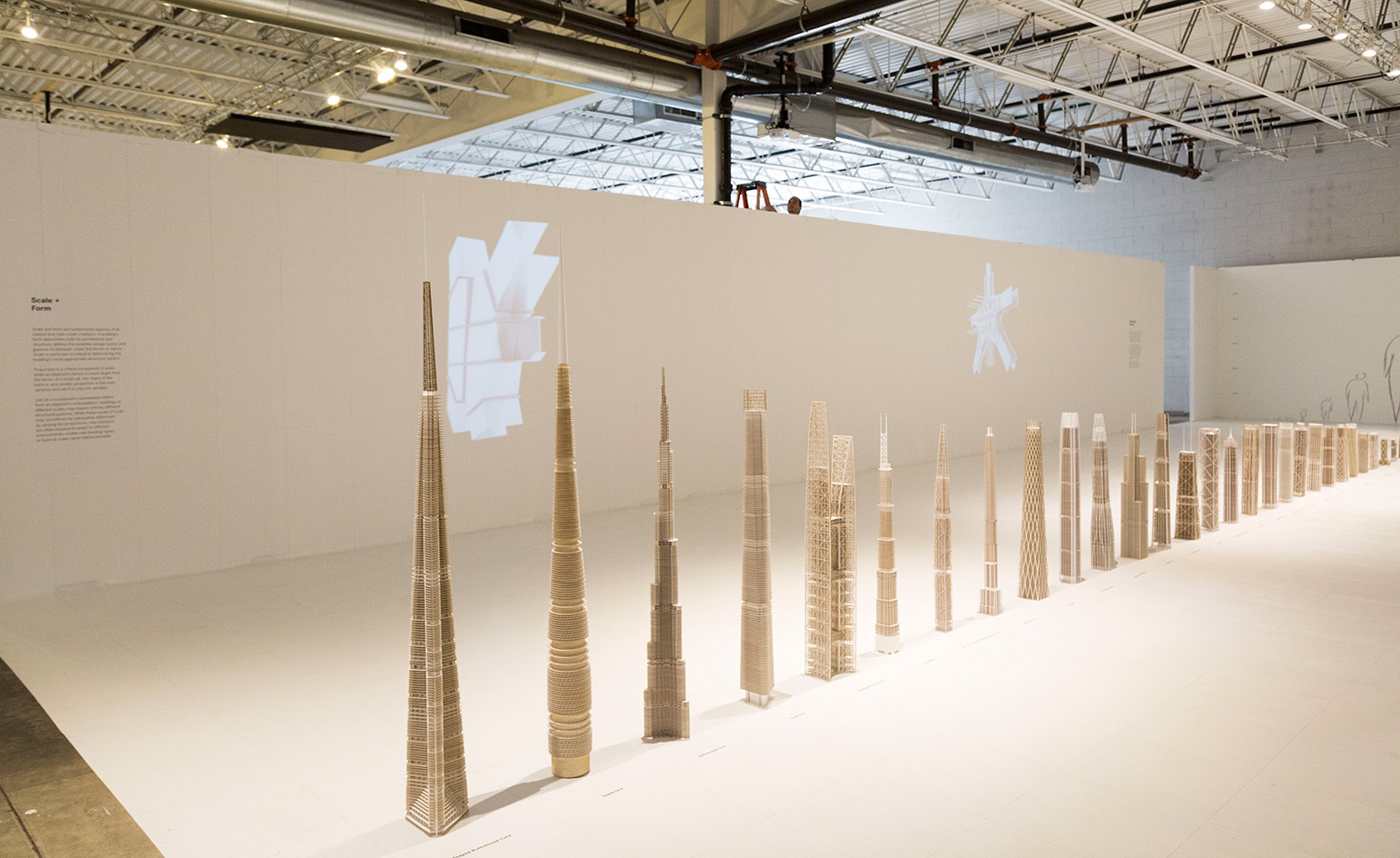

From tall to super tall, to mega tall – SOM buildings lined up in height order at 1:500 scale.

SOM is known for tall buildings, notably the Burj Khalifa in Dubai which standing at 828m owns the ‘tallest building in the world’ accolade. In one section of the exhibition, a line of beautifully intricate architectural models made of laser-cut museum board are arranged in height order. The space where they are displayed is a three dimensional grid of hand-drawn pencil lines, referencing the scale of the models which are each made at the same size ratio of 1:500.

‘So when you crossed that line you grew about 500 times,’ says Baker, a glint in his eye. Yoga mats encourage people to get down on the floor to look at the models at eye-level: ‘Imagine you’re 3mm tall’, says Baker, with the same glint.

It’s a smooth and satisfying journey, from tall, to super tall, to mega tall, moving from the comparably squat looking Exchange House in London at one end of the spectrum, to the streamlined trunk of the Lotte Tower in Seoul and onwards and upwards towards the fierce spike of the Kingdom tower in Jeddah, currently under construction and set to surpass the Burj Khalifa on completion, at the other end of the scale.

‘These shapes behave very differently, dramatically differently, you wouldn’t think so,’ Baker says of the ‘scrapers, which are labelled in the display by their structural system instead of their location or name. Each one of the designs for these super tall structures is first tested in SOM’s wind tunnel, a tool designed and built by the engineers and run by Hartz in the Chicago office. The team begin with a benchmark shape and then develop new designs from there, using models made of a lightweight (and very expensive) German styrofoam.

In this context, the exhibition is a tool – one that helps people to read a building, bridge or art work and identify the forces at play. It brings the engineering to the surface.

‘A structural engineer should always design a structure so that an architect feels bad if a structure is covered up,’ writes Baker in his essay ‘The importance of hierarchy’ in the book, a concept that, albeit humorously, relates to SOM’s founding principles of simplicity and structural clarity.

Take the The Poly Corporation Headquarters, where an eight storey cuboid is suspended in the atrium with a huge rocker mechanism, or the Hancock Centre in Chicago where the columns, diagonals and horizontals meet adroitly one storey above the ground, or at Exchange House in London where the transcending exterior arch expresses the primary function of the structure, to span the train tracks of Liverpool street station: ‘How do you tell a story with a building? You have to have order and hierarchy,’ says Baker, managing once again to directly connect a creative concept to mathematical methodology.

A model of artist Jaume Plensa’s artwork in a residential lobby of the Burj Khalifa.

For Baker, Hartz and the Research Gang, engineering always starts with creativity, and the final chapter of the exhibition presents SOM Engineering’s collaborations with artists, whom for Hartz are instinctive collaborators: ‘Because they typically try out a lot of stuff – and break a lot of stuff – they have a good idea of what works,’ he says of artists. ‘They make a full-scale model and see that it doesn’t work, they might not know how to solve it, but at least they know it doesn’t work.’

On display, SOM’s counter proposal to a Picasso maquette that would have fallen over at 50ft; photographs of Skyspace at Rice University – a permanent artwork by artist James Turrell for which SOM devised a viewing structure with a delicately hovering roof; and diagrams of Jaume Plensa’s enchanting composition of balanced cymbals in a residential lobby at the Burj Khalifa.

Baker steps back to admire images of Janet Echelman’s Dream Catcher work that stretches between two adjacent buildings on the Sunset Strip in LA. Coloured netting splays out into twisting shells evolving into contouring helix shapes, not dissimilar to some of the Research Gang’s models in the first part of the exhibition. ‘You say that’s art?’ asks Baker casually. ‘I see structure.’

The Research Gang's 'idea wall' in the exhibition. The projects on display are also dissected further in an accompanying book of the same title.

The exhibition is a tool in itself, one that helps people to read a building, bridge or art work and identify the forces at play.

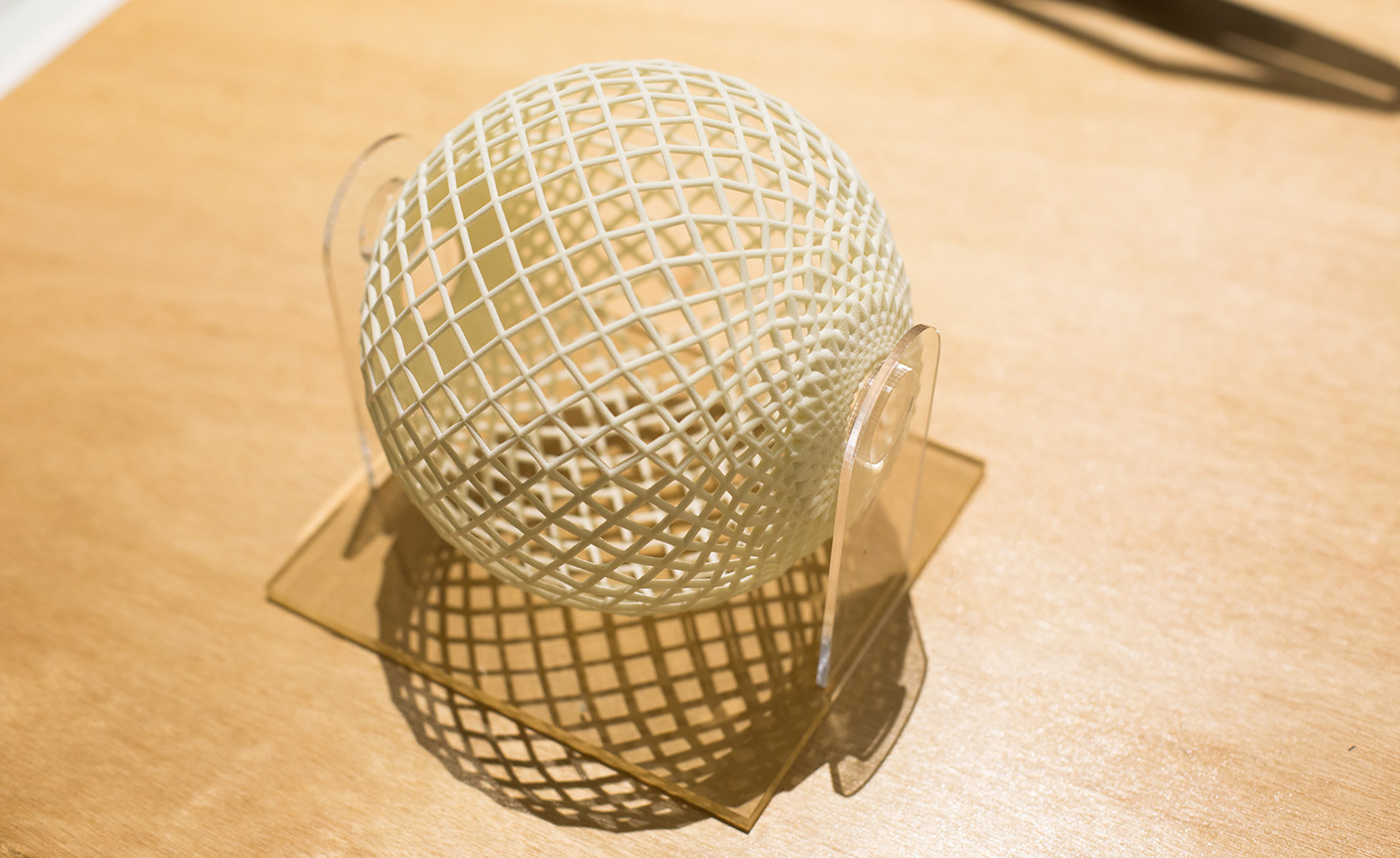

A model produced using the force density method.

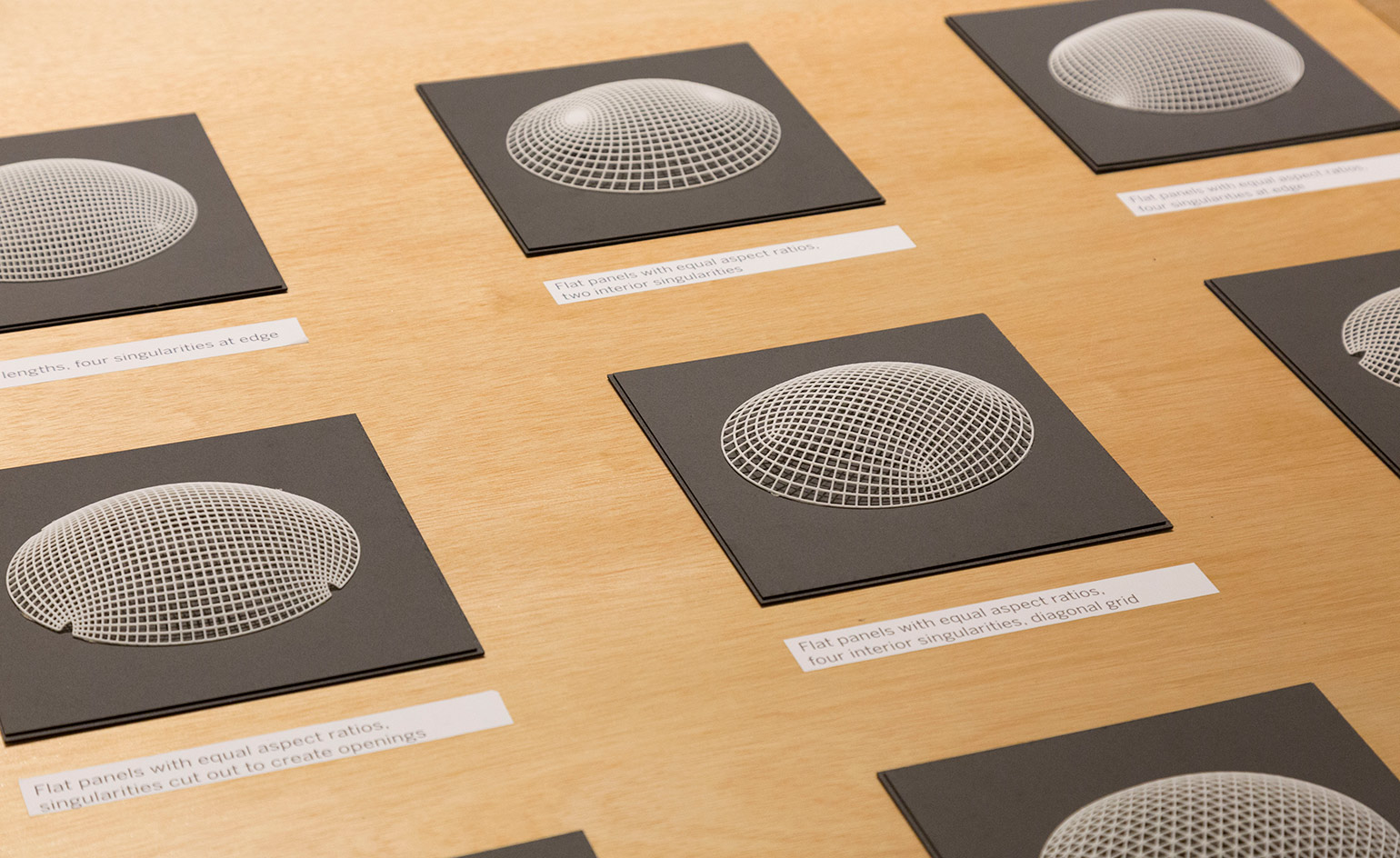

Models showing surface optimisation.

INFORMATION

‘SOM: Engineering x [Art + Architecture]’ is on view until 7 January 2018. For more information, visit the SOM website and the Mana Contemporary website

ADDRESS

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

345 N. Morgan St.

Chicago

IL 60607

USA

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.