Doshi Retreat at the Vitra Campus is both a ‘first’ and a ‘last’ for the great Balkrishna Doshi

Doshi Retreat opens at the Vitra campus, honouring the Indian modernist’s enduring legacy and joining the Swiss design company’s existing, fascinating collection of pavilions, displays and gardens

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The Vitra Campus in Weil am Rhein has accumulated a lot of 'firsts' over the years. There is Khudi Bari, the first building by Marina Tabassum outside of her home country of Bangladesh; the Vitra Design Museum, Frank Gehry's first design outside of the USA; and, famously, Zaha Hadid's first design to be built ever, the Vitra Fire Station.

Now, there's a new feather in Vitra's cap; welcome to Doshi Retreat, the revered and ever-growing campus' contemplative installation by Indian 2018 Pritzker Prize-winning architect Balkrishna Doshi, designed in close collaboration with his granddaughter Khushnu Panthaki Hoof and her husband Sönke Hoof. The structure, nestled in a green field next to Tadao Ando's Conference Pavilion, is not only the first piece of architecture by Doshi outside of his native India but also the first he designed to be completed posthumously – as it is also the last the modernist architecture master worked on before his death, in 2023.

Stepping inside the Doshi Retreat

Doshi Retreat is an homage to the great architect's legacy, and was conceived by him as a place for serenity and spirituality – a sensory journey of sound and feeling. Its origin story begins with Vitra chairman emeritus Rolf Fehlbaum's visit to India a while back, Panthaki Hoof recalls. 'It all started with a friendship between them. Together they visited a temple [the Modhera Sun Temple], which had a small shrine as part of it.' It inspired Fehlbaum to approach Doshi much later for the design of a 'space for silence' in the campus – something that would reflect the serenity and feelings of calm he felt when inside that small shrine.

Doshi created a concept around a number of notions and words, trying to distil the project's meaning. He went to Panthaki Hoof with it, saying, 'Here, this is the retreat.' This birthed the design, which the three architects developed together. 'Our question to answer was, what do you want to feel in this place? What does the shrine mean?' she recalls. The project progressed during the pandemic, and Doshi's passing left the husband-and-wife team (who have since worked on more projects linked to Doshi's legacy, such as the new toilet block at the Institute of Indology in Ahmedabad) to complete it.

The design evolved in an organic way as the three architects collaborated on it – growing beyond the compact space that Fehlbaum might have originally envisioned. 'We were a bit nervous as Rolf was expecting a 2x2m shrine, and this was bigger. It was all driven by intuition,' says Panthaki Hoof. She explains: ‘This architecture was born from a dream Doshi had of two interweaving cobras. From this subconscious vision emerged a written narrative, followed by a sketched concept composed of notes and evocations. It then evolved into an invitation to embark on a journey of discovery.’

The piece – part architectural pavilion, part art installation – sits near the edge of the campus, off the main entrance and a stone's throw from Vitra's manufacturing facilities and museum. This was not where it was originally meant to be, but the architects, walking through the site as they were working on their design, stumbled upon a piece of land next to the Conference Pavilion that felt like the perfect fit. Fehlbaum feels that this way, the project's 'silence answers to Ando,' as all the buildings in the Vitra Campus 'need to speak with each other.'

The parcel of land included three mature trees and a sloped terrain, so the design was crafted to weave between these existing plants, digging a 'river delta-like' path towards the main pavilion space. This journey into the pavilion is as exciting as the arrival at its inner sanctum. As the visitor moves towards the main room, the walls retaining the site's earth and greenery get taller, the guest's gaze urged to turn upwards towards the sky. It affords a feeling of seemingly leaving the prior surroundings behind.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

This experience serves as a smooth, gradual transition from the busy, working campus towards the retreat's meditative nature. Meanwhile, small rest stops on slightly higher ground are formed around the trees, offering opportunities to emerge, take a breath and look around.

The project's materiality is key. The pathways are flanked by weathered XCarb steel, the same cladding that wraps the main space too, which is matched in colour with the crushed bricks that line the approach. This reddish colouring creates a strong contrast with the leafy lawn, yet brings in a tactile feel. It also somehow accentuates the green element, bridging effortlessly nature and architecture – an element Vitra is keen to explore further. A masterplan for the wider campus is currently in development with Belgian landscape architect Bas Smets and involves the creation of mini forests across the entire site.

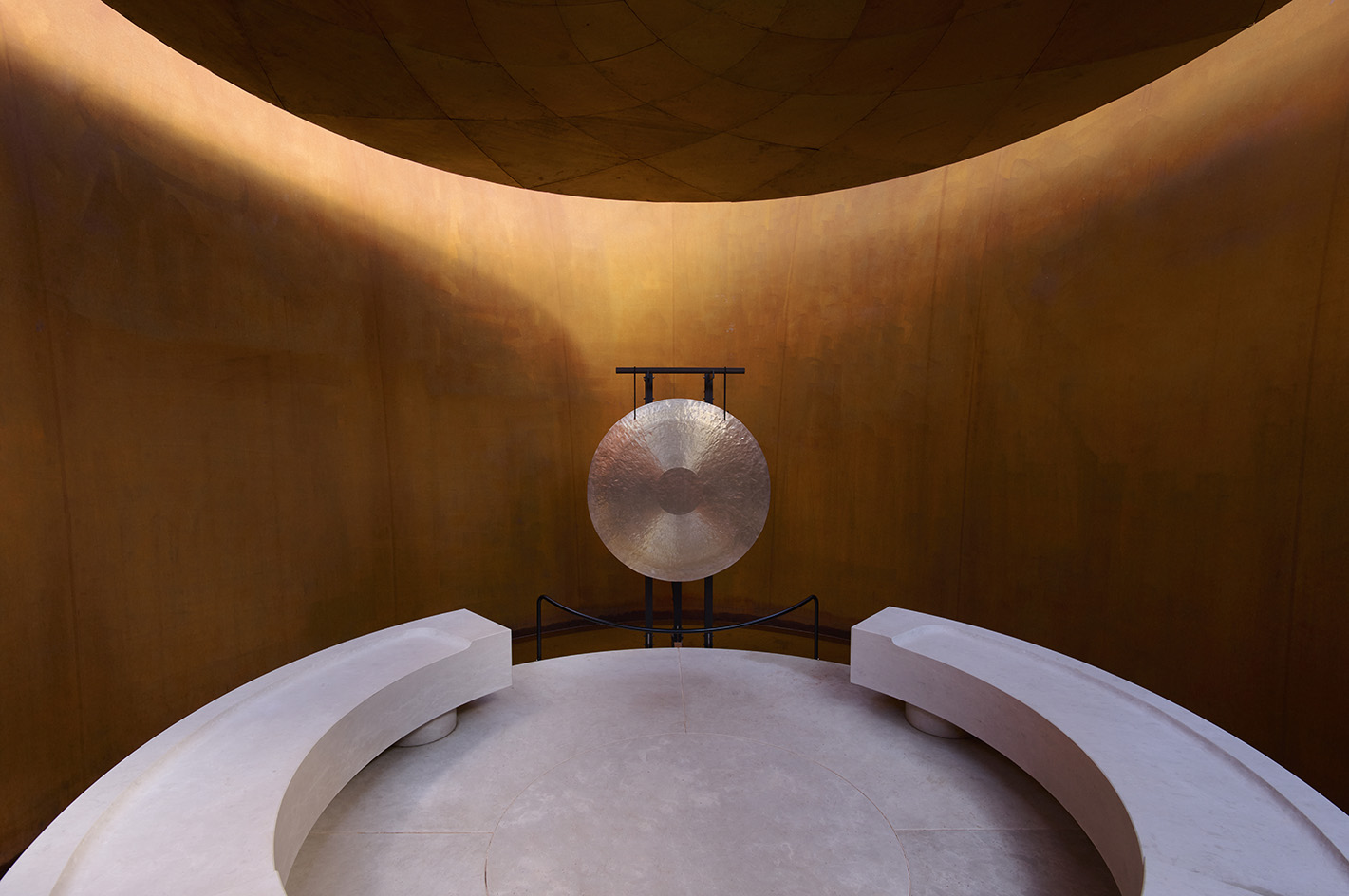

Inside the Doshi Retreat, a single, round chamber featuring a water pond and two simple, curved stone benches invites guests to sit and enjoy the gentle hum of a sequence of gong and ceramic flute that echoes in the room. This sound piece was faintly heard upon approach, too, but here it becomes more engulfing and subtly cocooning. A hand-hammered brass mandala crafted in India adorns the ceiling.

The project's main material, steel donated by ArcelorMittal, is set to age and change patina over time, adding to the pavilion's relationship with nature. As Hoof explains, it was produced using renewable resources to support a sustainable architecture approach. To that end, the foundations were not dug deep but were instead screwed in, so as to minimally disturb the existing land.

The Doshi Retreat was created as an invitation to solitude and a mindful pause – a space without a specific label. Its thoughtful nature and inauguration this week highlighted the Indian modernist's legacy – and his absence. What was it like, finishing the project without the great master, one of its three creators? Panthaki Hoof: ‘[Doshi] used to say that “silence is the most generous form of guidance”, and when he left, his absence was that silence for us.’

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).