Explore the landscape of the future with Bas Smets

Landscape architect Bas Smets on the art, philosophy and science of his pioneering approach: ‘a site is not in a state of “being”, but in a constant state of “becoming”’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

You might expect a landscape architect to put plants at the heart of their universe. In a sense, Bas Smets, one of the industry’s pioneering thinkers, does that, too, but it’s the triptych of philosophy, art and science that forms his true north star.

Bas Smets, photographed by Alexandre Guirkinger, in his studio in Brussels in July 2025

Perhaps it’s because landscapes are ever-changing – their very idea evolving over time and history – but also, as nature is alive and therefore a moving target, it physically morphs into something different every day. ‘You need to understand a site and work with it, and realise that it is not in a state of “being”, but it’s in a constant state of “becoming”,’ the Belgian landscape architect says. In this fluid and dynamic condition, references are needed, and while you might not immediately associate these three areas of culture and knowledge with landscape, to Smets, they are intrinsically linked.

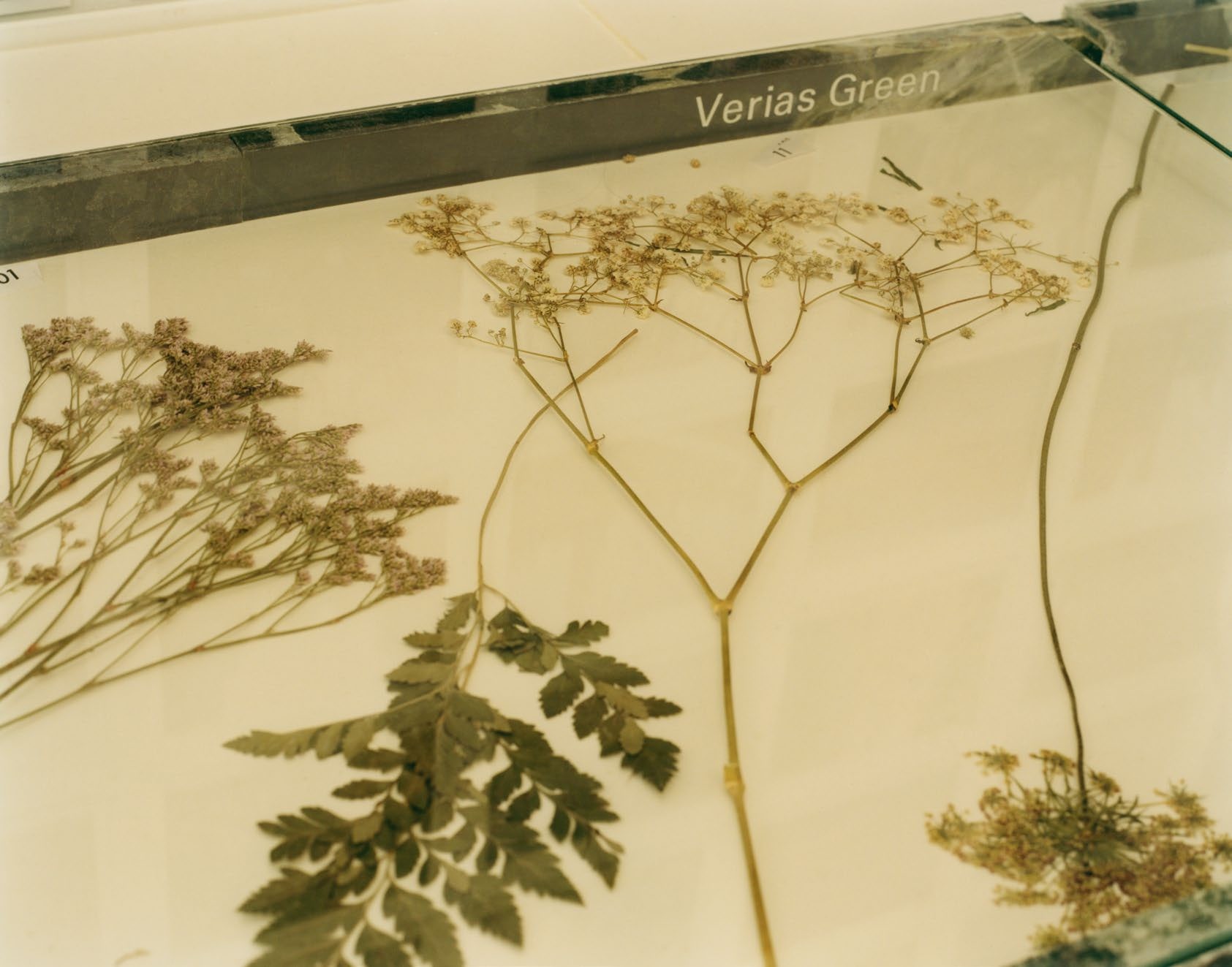

Pressed plants, images of which were used in the ‘Climates of Landscape’ exhibition, on show at Luma Arles until 2 November 2025

Explore the world of landscape architect Bas Smets

‘Landscape is a philosophy,’ he says. ‘It’s about understanding how to live on this planet. What is more philosophical than that? French philosopher Alain Roger said the land, the phase zero of a site, becomes a landscape through an artistic intervention, so art plays a key role here, too. In fact, the first recording of the use of the word “landscape” was by the painters from the Low Countries in the 16th century – it’s borrowed from the Dutch word “landschap”, which was first used to speak about a new genre in painting.’

Landscape is, above all, a mental construction, a way of organising the elements of the ‘land’. It is a concept that Smets has elaborated on and researched extensively for publications and exhibitions, including curating shows in 2016 and 2019 in Brussels’ Bozar art centre on both the history of notions of landscape and landscape within painting (in particular, Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s work).

A model of a project designed by Bas Smets to commemorate the victims of the March 2016 terrorist attacks in Brussels. Located in the Sonian Forest, just outside the city, the memorial features 32 trees (one for each victim who lost their life) planted in a circle, and offers those affected by the tragedy a place for a moment of calm contemplation

The science behind nature and how plants and all living things work, alone and together, is the third axis in Smets’ thinking. ‘Darwin contended that the environment does not shape the plants, but the plants shape the environment. Landscaping is setting in motion something that then continues to transform the space. You are hacking into an algorithm and into that logic. At the same time, the landscape is cyclical; it is about transformation.’

For Smets, working with a site’s natural environment to design a new landscape involves intense measuring and a deep comprehension of what is there, and what can be, in terms of biology, meteorology, geology and a host of other scientific fields, before even getting close to hatching a plan.

Items from the studio’s materials library

This quest for understanding, and an inherent curiosity, have always been a part of Smets’ thinking. He had a peripatetic childhood in Congo and Algeria (his mother worked for non-profits and his father was a civil engineer), before returning to Belgium to live on the outskirts of Brussels. As a young adult, he lived in Leuven and Geneva, where he studied engineering and architecture, and landscape architecture, respectively; and in Oregon, where he spent a year as an exchange student. ‘It was my first encounter with true wilderness and outdoor living,’ he recalls.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

As a landscape professional, he’s lived in Brussels, Paris and Arles, following his projects, while he regularly commutes to Cambridge, Massachusetts, for four months each year, teaching at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. These travels often inspired questions about life on our planet, prompted by different settings and human behaviours within them. While drawn to philosophy and mathematics as a young adult, he realised during his time at KU Leuven that what he enjoyed most was not designing the buildings, but everything else around them. He turned to landscape architecture and has never looked back.

Samples and objects in the studio’s materials library. The stone coffee table was designed by Eliane Le Roux

Spending six years in Paris, he worked for the office of landscape architect Michel Desvigne before setting up his studio in his living room in Brussels in 2007. A year later, he was joined by architect Eliane Le Roux, now his partner and associate, who serves as the studio’s creative director (as well as the lead of her own design atelier; she has worked on catwalk designs for Maison Margiela, among other fashion brands).

Le Roux’s artistic consultation and detail-orientated approach have guided the majority of the practice’s product output – from benches and other outdoor furniture to material compositions, fashion accessories, merchandise, and the studio’s brand identity, helping to glue it all together. ‘I don’t have a look, I have a methodology,’ says Smets – yet through Le Roux’s diligent eye, everything, from website design to project expressions, leaves the impression of a truly cohesive creative body of work. ‘It brings a whole new depth of thought, adding a layer of refinement to the landscape project,’ says Le Roux.

‘The idea of indigenous plants was invented in the 18th century. The reality is that nature has never cared about that’

Bas Smets

One of Smets’ first commissions was for a small private garden. His client, Swiss art patron and businesswoman Maja Hoffmann, wanted a design for her central London home’s neglected courtyard. Titled the ‘Sunken Garden’ and completed in 2011, the project became Smets’ first application of microclimate analysis. Realising that the space was consistently two to three degrees warmer than its surrounding environment, due to its enclosed nature, Smets tapped into this temperature potential, bringing in Tasmanian giant ferns and Yorkstone rocks, and transforming the relatively small patch of land, surrounded by tall façades, into a lush, leafy, almost otherworldly retreat.

‘I thought, I want to make the last prehistoric garden of London! Fern is one of the oldest plant species on the planet,’ he says. ‘I like to understand a climate, record it, respond to it and then change it. With this project, because of its enclosed nature, I realised there was the possibility of creating a microclimate using the right plants. Plants are an agent of change and transformation.’

The materials library

Smets’ approach expands to fictional landscapes, too. A piece he worked on with artist Philippe Parreno allowed him to imagine an entire environment from scratch. The project, a film titled Continuously Habitable Zones, made for a Fondation Beyeler show in Switzerland in 2010, involved creating a black garden on an imaginary planet set in a world of several suns. It was constructed in Portugal, and the result features an almost desert-like terrain made of a diamond dust ‘river’ and black plants (his research found that, due to the particularities of the light frequencies in such an environment, planting wouldn’t be green). ‘It was interesting, as it took this idea of inventing a landscape to a whole new level,’ he says.

Smets and Eliane Le Roux in the studio's Brussels office

Creating worlds and transforming landscapes sounds powerful, but moves such as these come with restrictions: how much are we meant to tweak and tinker with the natural world? ‘Plants move, all life moves, even continents move, but we don’t have to be naive about it,’ notes Smets, highlighting the need for a scientific approach and calculated steps. ‘The idea of indigenous plants was invented in the 18th century, which was a very peculiar moment in history. It was about putting categories on animals, people and plants; this one is from here, and that one is not. The reality is that nature has never cared about that. In today’s climate crisis, we have to think about the force of plants, their capacity, and look at them as an opportunity.’

Brussels, Saint Lazare

In this context, Smets’ take on the use of science in landscaping is not about dominating the environment, but about understanding it. ‘Our knowledge of how plants work is fairly recent,’ he says. ‘They’re intelligent in the sense that they make choices. I always look at what the vocation of a site dictates, and that is what drives the project.’

This dynamism is one of the reasons why he prefers to keep in touch with projects far beyond what’s often seen as the completion date. Ideally, he’d like to follow up with work at least two years post-completion, measuring, tweaking, supporting and adjusting as necessary.

London, Sunken Garden

This thinking became an integral part of the studio and is regularly used in Smets’ projects, such as in the hanging gardens at the Mandrake hotel in London in 2017; creating 17 public plazas with Office KGDVS, crafting greenery and shading across Bahrain’s historical Pearling Path; planting in La Défense in Paris in 2020, where groves of alder trees protect the ground level’s open, public spaces from excessive wind by creating an urban forest; and the 2024 reimagining of the Baumanière Les Baux-de-Provence hotel and restaurant gardens in the south of France. His biggest ‘experiment’, however, is the Luma Foundation’s Parc des Ateliers in Arles, in Provence.

Rome, Villa Medici garden

The site, an abandoned railway yard that had become an industrial wasteland, was given a new lease of life in 2014, when Maja Hoffmann began transforming it into a vibrant art campus. One by one, its existing warehouse structures were reimagined for art displays, residences and research (the list of collaborating architects includes Frank Gehry, Annabelle Selldorf, BC Architects and Assemble). Importantly, with Smets’ help, the campus’ outdoor areas, formerly a desert-like terrain where nothing grew, were completely revived into a lush and richly biodiverse ecosystem.

Paris, visualisation for Notre Dame's landscaping

According to Smets, crafting the park in Arles was almost like mimicking the appearance of life on the planet as it came out of a body of water. He worked with a range of specialists, from botanists to climate engineers and pedologists, to bring back biodiversity, and he ‘tried to imagine what nature would have done’, activating the land in stages, bringing earth, water and plants (more than 140 species and some 80,000 trees, shrubs and flowers) in calculated succession so they could mesh and feed off each other’s success. Wildlife followed effortlessly, and now 55 new species of birds frequent the park, which is also home to small animals, such as earthworms, frogs and hedgehogs.

Arles, Parc des Ateliers

If these gardens looked enticing when the project opened its doors to the public in 2021, they are positively thriving now, as Smets returned to Arles this summer to launch an exhibition on his studio’s work. A minimalist and immersive yet incredibly layered display, it tells the story of Smets’ pioneering thinking and, through examples of ongoing projects, showcases how carefully injected urban ecologies can transform our relationship with the environment (one that is currently in crisis, as the entrance canopy, decked with a climate stripe graph that shows the earth’s rising temperatures to this day, demonstrates). The Luma shop now stocks hats and bags designed by Le Roux to mark the exhibition and spread awareness for the landscape experience beyond the foundation’s borders.

New Orleans, Dauphine private garden

More experiments include ongoing projects in Antwerp, where he is currently designing a riverside park that draws on the city’s old canal system to create a dyke against rising sea levels, and research works, from his leading of the Belgian participation at the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale, where the country’s pavilion becomes a ‘living’ laboratory that shows how plants can be leveraged to alter indoor climate, to the work at his Harvard studio, titled ‘Biospheric Urbanism’. The latter’s intense analysis led to the proposal to create artificial microclimates by boosting Athens’ green infrastructure, for example, by temporarily planting secondary archaeological sites to bring the nature-deprived Greek capital’s temperature down using the power of plants.

Paris, La Defence

The redesign of the surroundings of Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral following the devastating 2019 fire is, no doubt, his most high-profile upcoming project. For his 2021 international competition-winning scheme, Smets used the same climatic approach to create an ‘augmented landscape’ around the monument. His terrain and climate analysis aimed to tap into nature’s forces to not only slow down overheating but significantly lower perceived urban temperatures around the Île de la Cité in the Seine. Working with architecture studios Grau and NGA, Smets completely reimagined views, routes and levels on the land mass.

Himara Waterfront

An abandoned car park beneath the cathedral will be transformed into a visitor centre, offering views of the foundations as seen 800 years ago, when the cathedral was first built and before soil sediments and construction raised the ground to its current level. An open plaza, paved with striated Burgundy stone slabs, will be covered with a thin film of water daily, not enough to get shoes wet but just enough to freshen the surroundings naturally through evaporative cooling. (The striation was Le Roux’s idea and not only creates an optical illusion by visually extending the floor pattern inside the cathedral, but also enhances the surface’s anti-slip properties.) Meanwhile, a redesigned green park, complete with more than 165 new trees, as well as a rethought surrounding road system, will turn this part of central Paris into a mini green paradise.

‘Our knowledge of how plants work is fairly recent. They’re intelligent in the sense that they make choices’

Bas Smets

A first phase, the small plaza directly outside the cathedral’s entrance, was completed in 2024, marking the monument’s reopening. While works on the wider site will continue until 2028, this element offers a glimpse into the future – one that Smets is hopeful landscape will play a key role in, as our environment, natural and human-made, is inescapably present and therefore ever-more critical, both in terms of our wellbeing and the very survival of our planet. As he highlighted at the opening of his show in Arles in July 2025, ‘we are always surrounded by landscape’.

‘Bas Smets: Climates of Landscape’ is on show until 2 November at Le Magasin Électrique at the Luma Foundation, Arles, luma.org, bassmets.be

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).