From new compacts to SUVs, car makers are charging towards an electric future

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

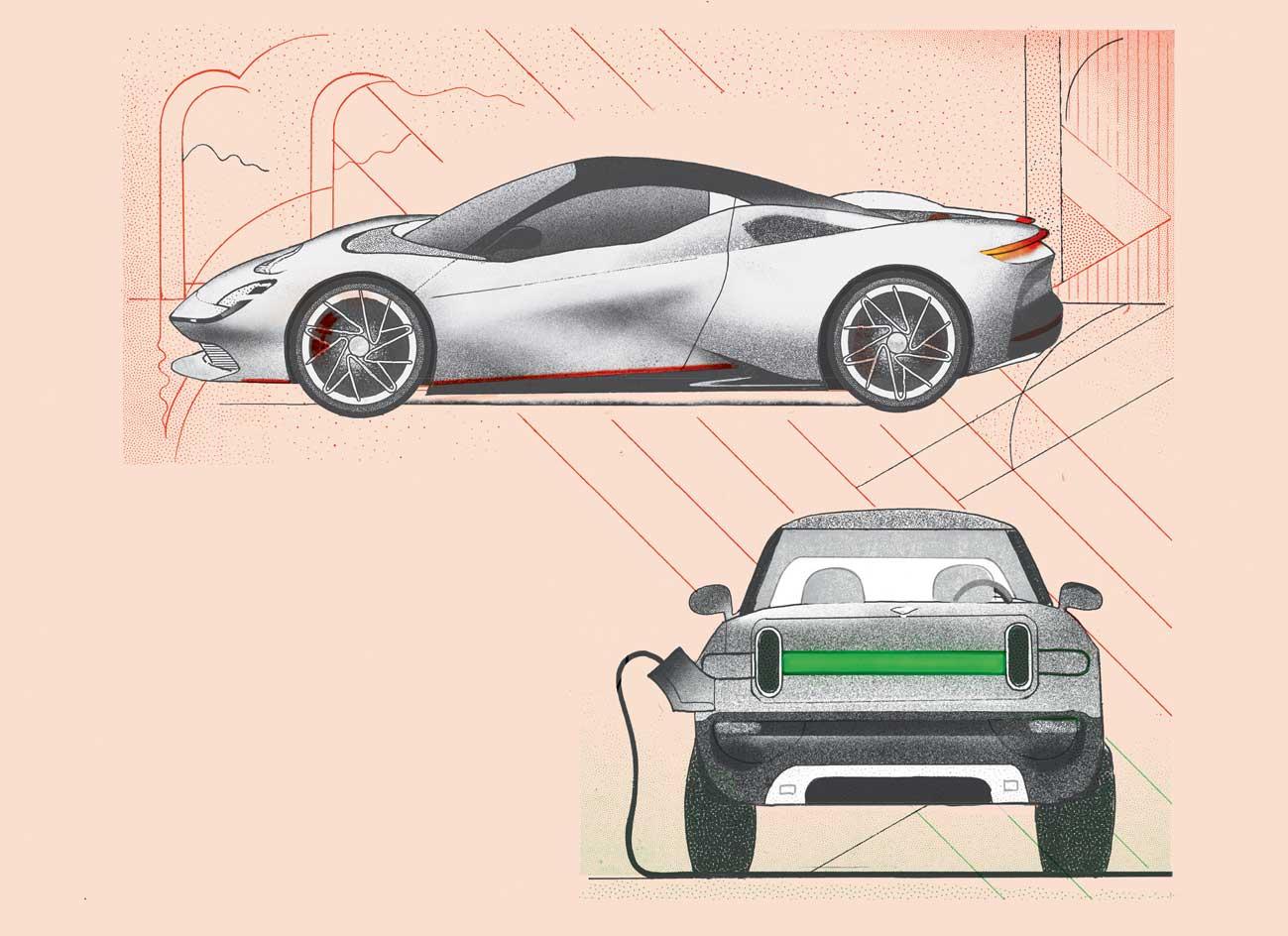

Pictured top, Pininfarina Battista (around $2m). Pitched as Italy’s ‘most powerful ever sports car’, the Battista packs 1,900hp of battery power within its sleek frame. Go easy, and you’ll get a 280-mile range. pininfarina.com. Pictured bottom, Rivian R1T Truck (available in 2020). Boasting a 400-mile range, the Rivian Truck (also joined by a new SUV) is an all-American utility vehicle hoping to bring rugged, go-anywhere chic to the EV market. rivian.com.

As of this month, you’ll be able to put down a deposit on a brand new Volkswagen ID, a Golf-sized all-electric vehicle that comes pre-loaded with a weight of expectations. The car itself won’t be shown to the public until this September’s Frankfurt Motor Show, and this sight-unseen marketing strategy is hitherto unknown for a volume car manufacturer. Two things have changed the automotive landscape in the past decade. The first is the unpredictable combination of aspiration, ego, innovation and bottomless funds that has driven the American manufacturer Tesla to the forefront of the industry. The second is the fallout from the Volkswagen emissions scandal, a corporate cluster-bomb that had the unintended consequence of vastly accelerating change by killing off the very fuel it was trying to promote.

Electric vehicles (EVs) are now all the rage. At this year’s Geneva Motor Show, EVs were thick on the ground, from high-end sports cars to compact city runarounds, over-styled crossovers, outlandish luxury SUVs and conventional family cars. Almost overnight, the EV market has blossomed to fill every niche. For the industry, the shift to EVs is a no-brainer; brands will flourish under a system that promotes zero-emission driving. Over a century’s worth of automotive heritage will simply shift gear to accommodate a new generation of car buyers. For governments, cities and the public, the answer isn’t so clear. Tax revenues from fuel sales look set to plummet, while congestion and auto-centric urban design will persist.

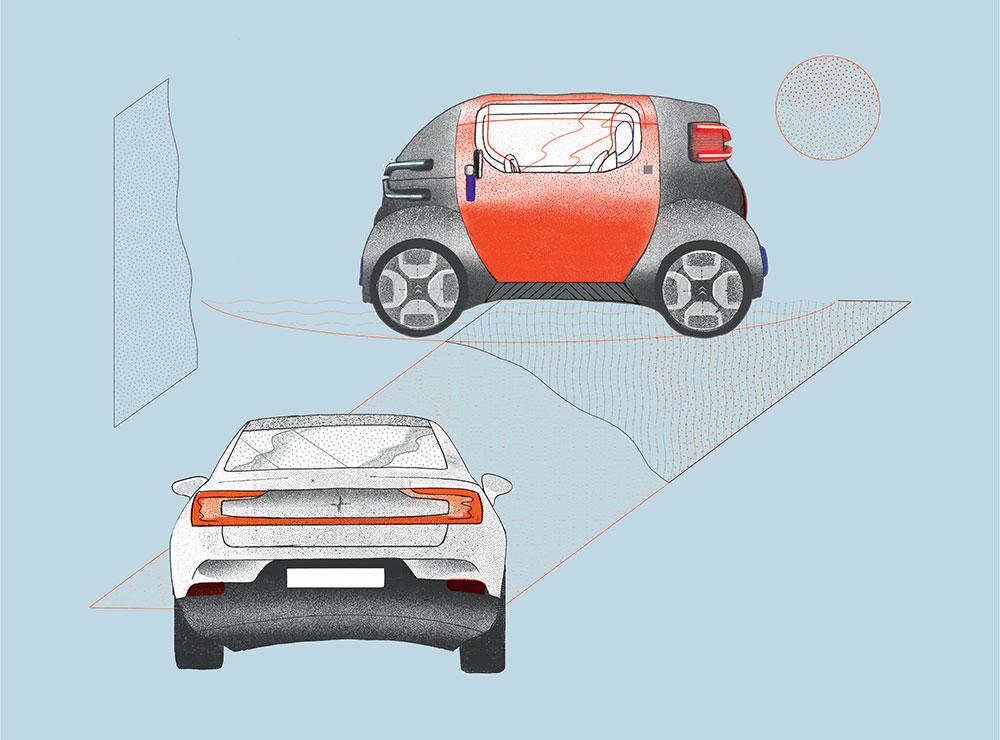

Pictured top, Citroën Ami One (concept only). Citroën’s Ami One is a nod to the French firm’s innovative small city cars of the mid 20th-century. The two-seater is aimed squarely at the urban market. citroen.com. Pictured bottom, Polestar 2 (from €59,900). An all-electric fastback design, the Polestar 2 promises a new approach to car ownership, with seamless digital integration and smart minimal design. polestar.com.

For aspirant carmakers, this shift seemed an opportunity. Building an auto brand from scratch is a colossal undertaking, but EVs have lowered the barrier to entry, with shared platforms and far lower start-up costs. Where Tesla led, others followed. The clean-slate approach of new names such as Lynk & Co, Byton, Nio, Faraday Future and the revived Fisker brand, or even the secretive Dyson project, suddenly all seemed to have a place at the table. That window of opportunity may be narrowing, though.

Volkswagen has dug deep into its corporate pockets and set about reinventing itself as an electric powerhouse. By 2028, it promises 70 new electric models across its various brands; it claims it will be a CO2-neutral company by 2050. Other manufacturers are also taking stock. In 2017 Volvo was first to announce that all its new cars launched from 2019 would be hybrids (either ‘mild’ or ‘plug-in’) or entirely electric, with 50 per cent of its fleet being pure electric by 2025. Honda also recently committed to the total electrification of its European sales output by 2025. Porsche (a Volkswagen subsidiary) is making a massive push, bringing the sleek Taycan saloon to market later this year, with other EVs to follow. Other makers are adopting the strategy of electrifying small cars and keeping hybrid tech for larger vehicles.

For many car owners, the EV is still an unknown. Big name support might bring confidence, but other companies are resorting to another tactic: pure temptation. Electric vehicles represent a new design opportunity in an image-obsessed industry. BMW’s i division debuted in 2013 with two defiantly distinctive models, the i3 and the i8. Jaguar’s i-Pace is the style-obsessed manufacturer’s most glamorous and desirable car, while debut EVs from Audi, Mercedes, Mini, Hyundai and Kia all major heavily on design. Honda is bringing out a chic little city car in 2020, previewed by the delightful e Prototype, while other quirky urban electrics include Quadro’s eQooder (bolstered by a collaboration with Tod’s), Citroën’s Ami One, Seat’s Minimó and Fiat’s Concept Centoventi (a rather late entry for a company with gold-star heritage in the urban sector). Brands such as Polestar and Lynk & Co (both owned by Chinese manufacturer Geely, which also owns Volvo) combine contemporary design with new ownership models, reasoning that future drivers might not need to have 24-hour access or responsibility for their own vehicle.

RELATED STORY

Other start-ups are going further still to bring EVs into every conceivable niche. Rivian is hoping to create an ‘electric adventure vehicle’ sector. The American company’s R1S SUV and R1T pick-up truck are due on the road towards the end of next year and boast a 400-mile range (‘San Francisco to Yosemite and back’). Rivian’s vice president of vehicle design, Jeff Hammoud, describes an emphasis on design from the outset. ‘The first thing we paid attention to is the proportion,’ he says, explaining that the company’s EV platform (which it may license out) allows for a plethora of body styles and functions. Branding is also consciously different. ‘Trucks have grilles to communicate strength and power – they tend to be very big. We don’t need a grille, but we have kept everything intelligent and blunt. That identity also has to scale into the future.’

Hammoud describes Rivian’s style as a ‘Patagonia jacket, not an Armani suit’, emphasising the brand’s inherent functionalism. The rebirth of Lagonda, on the other hand, is pitched at the consumer of luxury attire. Part of Aston Martin since 1947, Lagonda resurfaces in 2021 with an SUV, previewed at Geneva by the All-Terrain Concept. Purely electric from the outset, the target is the Rolls-Royce market and the ethos is contemporary luxury, underpinned by cutting-edge craft, materials and tech. ‘We aim to reimagine luxury travel in a way that could only be done in the 21st century,’ says Gerhard Fourie, Aston Martin Lagonda’s director of marketing and brand strategy. ‘We don’t see luxury and technology at opposing sides of the spectrum; together they can create wonderful experiences.’ Luxury buyers seem keen to embrace the new. ‘We obviously get the strongest reaction from customers who are open to change,’ Fourie admits. ‘They have strong views on design and quite a healthy relationship with the technology in their lives – I’d say they are “technology enabled” rather than “technology obsessed”.’

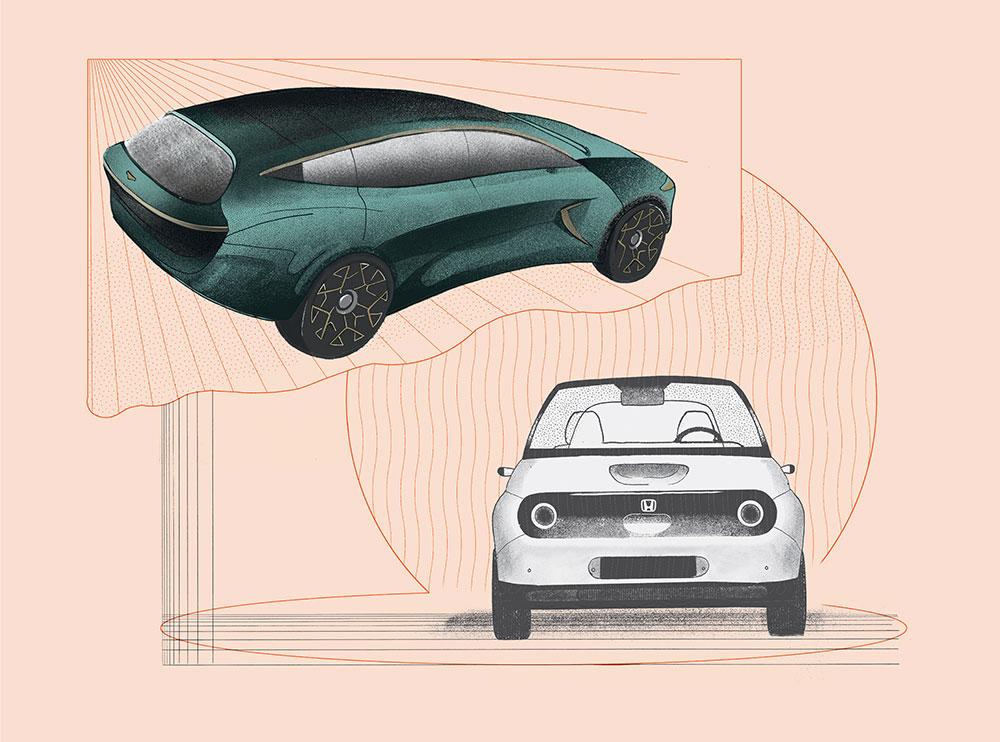

Pictured top, Lagonda All-Terrain Concept car (available 2021). Lagonda’s All-Terrain Concept will hit the market in 2021 as the first luxury electric SUV. The British brand, revived in 2018 by Aston Martin, is majoring on design and quality. lagonda.com. Pictured bottom, Honda e Prototype (available 2019). Inspired by the original Honda Civic, this prototype previews Honda’s ultra-compact city car, a neat four-door with retro styling, a chic interior and, of course, zero emissions. honda.com

Also at the high end you have the Pininfarina Battista, an electric hypercar that’s out to steal the super-rich away from their Ferraris. ‘If we want to do justice to the brand we have to start where people perceive us,’ says Automobili Pininfarina’s CEO Michael Perschke, who describes the 89-year-old design house as the ‘Château Lafite of car design’. The Battista – named after the brand’s founder, Battista ‘Pinin’ Farina – is intended to be the ‘most powerful Italian sports car ever made’. With a motor in each wheel, the car will have a scarcely credible 1,900hp (over 25 per cent more than its conventionally powered rival, the Bugatti Chiron). ‘The design is a balance between radical technology and timeless Pininfarina design,’ says Perschke. ‘We want people to fall in love with an electric car for the first time.’

For well over a century, the motor car has been a totem of identity as much as a mode of transport, embedded for better or worse within society and culture. The success of all these cars depends on the premise that the automobile is here to stay, yet calls to curb or cut out car use are given increasingly serious consideration. Early EV adopters might have already reaped all the available rewards, sucking up the rebates, subsidies, free parking spots and absence of tolls. The other as yet unanswered question is that of charging. Although manufacturers are helping new networks seed across the road system, what’s really needed is a top-down overhaul of park and charge infrastructure, from city streets to supermarkets. That’s a whole different story. What’s certain is that for a time at least we’ll have more cars, not fewer, as EVs blur the lines between concept and reality and find new ways of seducing the drivers of the future.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

As originally featured in the June 2019 issue of Wallpaper* (W*243)

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.