St Pancras Renaissance Hotel opens Booking Office 1869 restaurant

Booking Office 1869 restaurant, at the St Pancras Renaissance Hotel, is set to become a new London hotspot. Developer Harry Handelsman and designer Hugo Toro tell us about its creation

Michael Sinclair - Photography

‘It is insane that I own this building,’ says Harry Handelsman, his eyes widening with genuine wonder. Those familiar with Handelsman’s work might find it strange that he could still be impressed by owning any building. He is, after all, one of the most recognisable real estate developers in London, with a portfolio that includes Manhattan Loft Gardens, a self-sustaining mini-city of apartments, restaurants, rooftop gardens, and a cultural centre in the East End; as well as elite watering hole The Chiltern Firehouse.

But in the context of the St Pancras Renaissance Hotel, Handelsman’s most ambitious project and quite possibly the most significant renovation in the city’s recent history, his astonishment is easily understood.

A sprawling Gothic Revival building in the heart of London, the Renaissance Hotel has, since it opened in 1873, functioned as a unique mirror for the city itself. To chart the hotel’s history is to understand the shifting fabric of London’s cityscape; from its days as a gem of the Victorian era’s bombastic industry, to its dissipation into a derelict outpost for illegal raves during the 1980s, and its integral role in the development of the Eurostar and London’s hyper-globalisation in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Now, London is poised to enter a new era as it emerges from the wake of Covid-19 and enters a world reverbatring with its effects. If a city’s infrastructure offers an accurate barometer of cultural shifts, then it should come as no surprise that the St Pancras Renaissance Hotel is set to enter its own new epoch. On 16 November 2021, the hotel opened its new restaurant and bar, Booking Office 1869.

It is a landmark restaurant for a city on the brink of something new, with a population – emerging from 18 months of restrictions and lockdowns – that is perhaps ready to indulge in revelry and glamour but without unseemly excess. It is a place that, as Handelsman puts it, ‘makes people feel both privileged and comfortable’.

The revitalisation of the St Pancras Renaissance Hotel

Having a conversation with Handelsman feels like pulling back the curtain and taking a seat with London’s very own Oz. Since starting Manhattan Loft Corporation in 1992, he has overseen real estate ventures that have triggered the regeneration of entire areas of the city – from Stratford to Clerkenwell and King’s Cross. When I ask him about the best part of his job, he instantly replies, ‘creating neighbourhoods’.

The key to Handelsman’s success is his acute understanding of how commerce and culture operate with the city. For him, a real estate venture can only be successful if it nurtures the appeal of its neighbourhood. Cultural capital begets economic capital – people will not spend money in a place unless they think it is an interesting place to go, and it will only be an interesting place to go if there are cultural developments happening around it.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

King’s Cross is a prime example of this. When Handelsman got involved in the project in the early 1990s the Renaissance Hotel was a crumbling ruin in a desolate neighbourhood. Once a crowning jewel of Victorian London, the hotel fell out of favour as it moved into the 20th century, largely because its rooms lacked ensuite bathrooms (chamber pots were the norm when it was built).

Hugo Toro (left), designer of Booking Office 1869, wearing Dior, and Harry Handelsman (right).

In 1997, Handelsman’s Manhattan Loft Corporation embarked on a painstaking, ten-year and £200m renovation project of the hotel. A premium was placed on preserving the historic elements of the space, despite the increasingly exorbitant cost of doing so. At one point, 500 art restorers were hand-painting the fleur-de-lis and medieval manuscript illuminations that decorate the walls, while a team of architects and specialist contractors worked to outfit the space with modern amenities without disrupting original features.

When the hotel opened in 2011, it was a staggering achievement of architectural renovation and, perhaps most significantly, offered people a desirable place to spend time in what was otherwise a neighbourhood most people simply passed through. That shift spurred a number of other developments that have made the King’s Cross area into the vibrant hub it is today. From the relocation of Central Saint Martins’ campus to the area (‘a genius move’ in Handelsman’s opinion, as it established a legion of young, creative people in the neighbourhood), and the Thomas Heatherwick- designed shopping destination Coal Drops Yard.

Booking Office 1869: a new London hotspot

‘Perfection is almost impossible to achieve, but this is the closest I have ever seen to perfection,’ says Handelsman of Booking Office 1869. While that may sound bombastic, you immediately see what he means when you enter the space.

Booking Office 1869 restaurant and bar is, as its name suggests, located in the former ticket office of St Pancras station. Every aspect of its redesign has been masterminded by the French-Mexican designer Hugo Toro. Sitting down with Toro, it becomes very clear, very quickly that he has the unrelenting energy and stupefying array of talents that define the brilliant multihyphenate of our era.

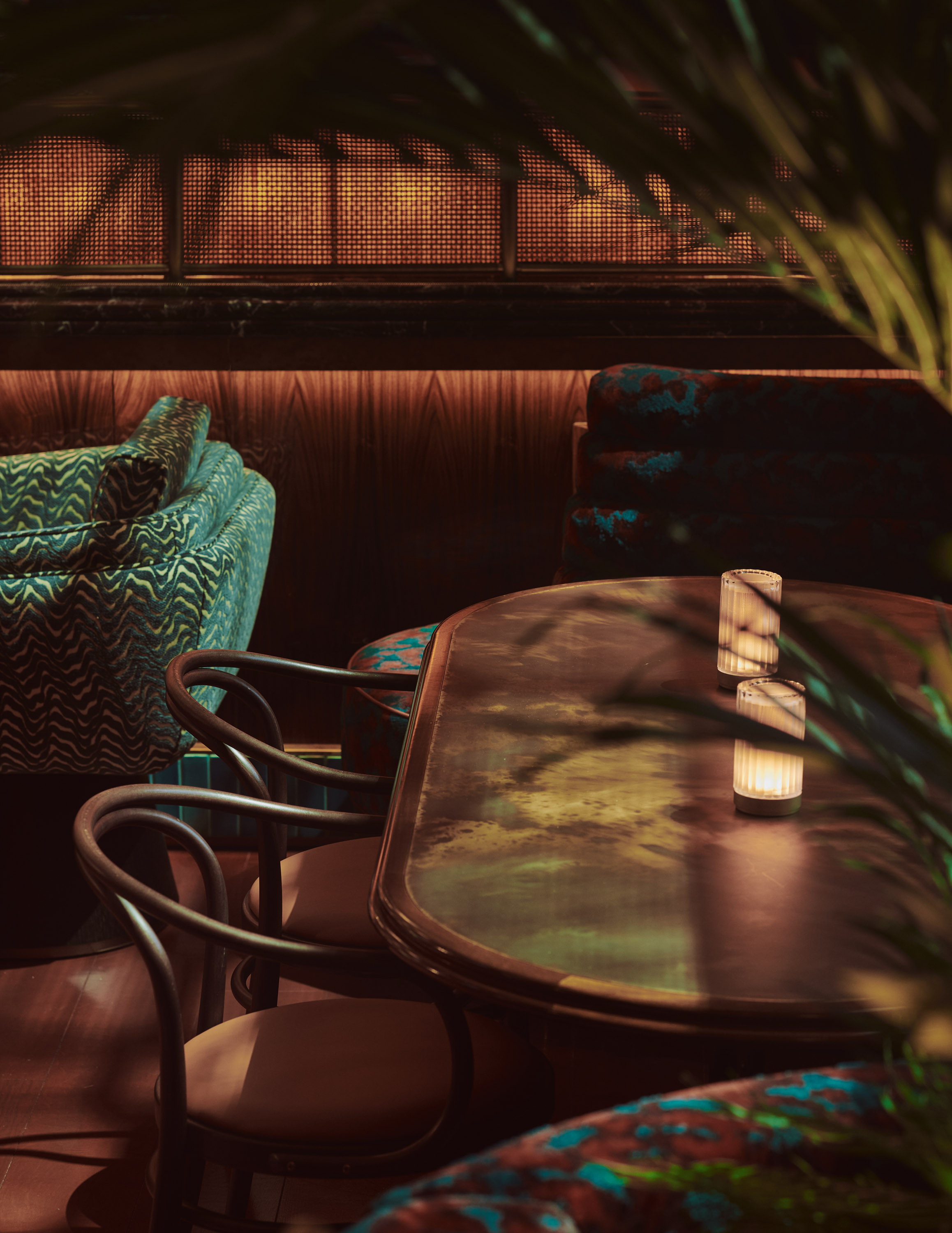

Toro has designed almost every aspect of the space – from the chandeliers and the chairs to the upholstery fabrics and the minuscule strips of metal grating that skirt some of the booths. The result is a dazzling space that walks the tightrope between a modern and a retro aesthetic.

Toro achieved this sense of timelessness by creating what he calls ‘roots’ or memory triggers for visitors. ‘I like when you don’t know if [a space] has been there for 30 or 40 years, or if it has just been done yesterday,’ he says. ‘It’s important for me to give these roots to the visitors. For example, this table,’ he adds, pointing to one of the dining tables with its strange, burnished metal top. ‘I wanted to have this oxidised pattern on the brass. When people saw it they said, “Are you sure?” But then the other day this girl came in here and said, “Oh, it's so funny, this reminds me of my grandmother’s table.” I want to create [those moments].

‘I’m not here to design something beautiful but to give emotion to someone,’ Toro continues as he walks around the space pointing out more and more details – fabric patterns inspired by the Renaissance motifs of the hotel walls but abstracted to appear more contemporary, grand chandeliers with 3D-printed features. The effect is a space that manages to be communal by hitting on people’s individual memories.

That play between the private and the public is played out in the layout of the space too, which transitions from communal bar areas to snug booths.

‘I wanted to create an experience whereby you arrive here and are stuck in time – you’re waiting for your train, for your lover, you’re waiting for someone from the hotel, or you’re just waiting at the bar by yourself. Here, you have different typologies [of space], different typologies of people, and of sequences and time.’

The Booking Office 1869 menu has been conceived by Patrick Powell – former Chiltern Firehouse head chef and current head chef of Allegra restaurant and bar – and features old-school classics with a sophisticated spin. Think fried chicken bites with yogurt and lime dressing; a Waldorf salad with burrata, beetroot, apple and lentils; and the house burger with Béarnaise sauce, caramelised onion, bacon, and Ogleshield cheese.

A complementary cocktail menu has been conceptualised by bar manager Jack Porter, with drinks that blend favourite ingredients from the Victorian era for contemporary tastes. Espresso martini lovers will be happy to know that the drink is served on tap, with an almond and gold powder garnish inspired by the restaurant's chandeliers.

Overall, Booking Office 1869 is an exceptional space that lives up to the iconic status of the Renaissance Hotel. No doubt it is a welcome addition to the London scene, whether for a glamorous night out or an intimate meeting with loved ones, or potentially soon to be loved ones, in a city that has surely missed the possibilities of those evenings.

INFORMATION

Mary Cleary is a writer based in London and New York. Previously beauty & grooming editor at Wallpaper*, she is now a contributing editor, alongside writing for various publications on all aspects of culture.

-

Mexico's Palma stays curious - from sleepy Sayulita to bustling Mexico City

Mexico's Palma stays curious - from sleepy Sayulita to bustling Mexico CityPalma's projects grow from a dialogue sparked by the shared curiosity of its founders, Ilse Cárdenas, Regina de Hoyos and Diego Escamilla

-

Everything to look forward to in fashion in 2026, from (even more) debuts to the biggest-ever Met Gala

Everything to look forward to in fashion in 2026, from (even more) debuts to the biggest-ever Met GalaWallpaper* looks forward to the next 12 months in fashion, which will see the dust begin to settle after a year of seismic change in 2025

-

Five watch trends to look out for in 2026

Five watch trends to look out for in 2026From dial art to future-proofed 3D-printing, here are the watch trends we predict will be riding high in 2026

-

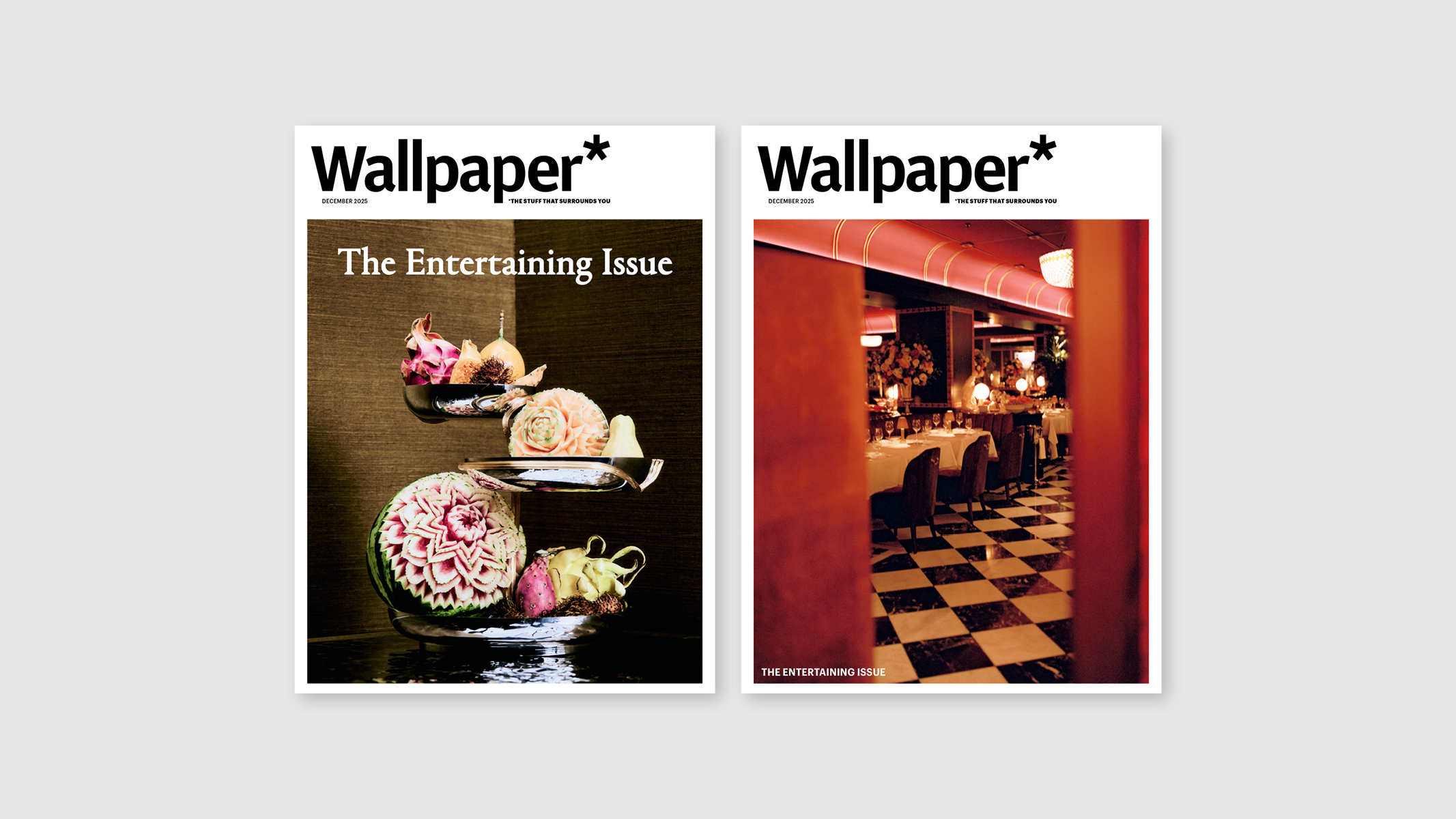

Unleash your socialising superpowers with the Wallpaper* Entertaining Issue, on sale now

Unleash your socialising superpowers with the Wallpaper* Entertaining Issue, on sale nowGet your sublime supper party started – or hit the town in style – with the December 2025 issue of Wallpaper*, on newsstands now

-

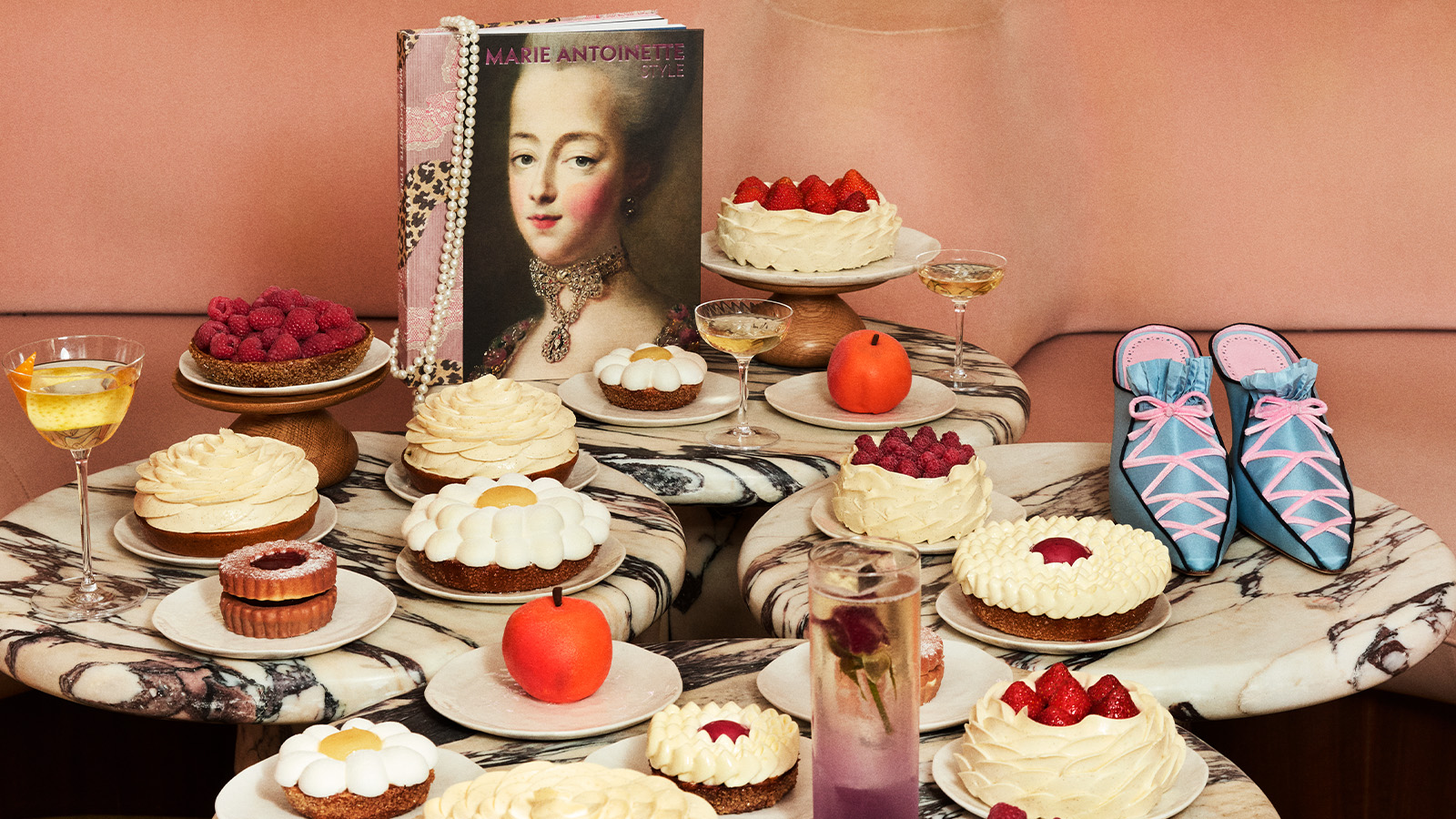

Let them eat cake (and drink cocktails) as Manolo Blahnik and The Berkeley unveil a new menu fit for a queen

Let them eat cake (and drink cocktails) as Manolo Blahnik and The Berkeley unveil a new menu fit for a queenThe hotelier and renowned designer has teamed up on an exclusive cake and cocktail menu to celebrate the V&A’s landmark exhibition ‘Marie Antionette Style'

-

The artistry of Japanese wine

The artistry of Japanese wineFine wine from Japan may not yet register highly on the radars of most oenophiles, but for those who know, it's a hugely rewarding and rich tapestry of flavour. Drinks expert, Neil Ridley visits London's Luna Omakase for the launch of a new dedicated Japanese wine pairing menu

-

From The Fat Badger to The Bull, how Public House is redefining the British pub

From The Fat Badger to The Bull, how Public House is redefining the British pubInside the design-driven food group putting provenance, craft and community back at the heart of pub culture

-

Guests dined on Bangladeshi-inspired cuisine at the Serpentine Summer Party 2025

Guests dined on Bangladeshi-inspired cuisine at the Serpentine Summer Party 2025The party marked the 25th anniversary of the Serpentine Architecture Pavilion – and celebrated this year’s design by Bangladeshi architect Marina Tabassum and her Dhaka-based firm

-

Rémy Martin and Anish Kapoor: art meets cognac in London

Rémy Martin and Anish Kapoor: art meets cognac in LondonThe cognac house and the artist unveiled a limited-edition XO decanter and a new sculpture in London at a recent event at the Institute of Contemporary Arts

-

Mark your calendars for Mount Street Neighbourhood Summer Festival, a feast for the senses

Mark your calendars for Mount Street Neighbourhood Summer Festival, a feast for the sensesThe event, 12-14 June 2025, showcases the mix of food, art and community in the heart of London’s Mayfair. Here's what to expect, from afternoon tea to aperitivo, film screenings to biodynamic flowers

-

Healthy chocolate? Eat it at Makers, London’s new Lebanese chocolatier

Healthy chocolate? Eat it at Makers, London’s new Lebanese chocolatierLocated in Chelsea, Makers is a new ‘healthy chocolate’ shop offering treats free of refined sugar, seed oils, wheat and dairy – and it tastes delicious