Vienna Biennale for Change dissects our digital future

In Vienna, something momentous is brewing that could provide a roadmap for navigating our digital future. Through nine distinctive exhibitions, the 2019 Vienna Biennale for Change aims to help us sift through the dizzying cocktail of rhetoric, buzzwords and media fearmongering to make sense of it all.

As Biennales go, this one occupies a unique corner of the landscape. Since its inception in 2017, it’s found a niche in merging disciplines and inspiring change. According to Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, General Director of MAK (Museum of Applied Arts) and initiator of the Biennale, dividing to conquer is never the answer. ‘Keeping creative disciplines separate is never a good thing’ he says. ‘No discipline is inferior. What you need is a dialogue.’

This year’s title, ‘Brave New Virtues: Shaping Our Digital World’ stems from Aldous Huxley’s 1932 dystopian novel Brave New World. But where do dystopias come into this, what exactly are ‘Brave New Virtues’ and how do we practice them?

The post-war era promised consumption with no limits, breeding a culture of instant gratification and abundant choice. But with this wealth of potential came the exploitation of resources, little regard for conscious consumption, a scenario where supply exceeded demand, and eventually, a global climate crisis.

Installation view of ‘CLIMATE CHANGE! From Mass Consumption to a Sustainable Quality Society’. Left, Greenfreeze 2, by Eoos, 2019. Right, Kitchen-Cow, by Eoos, 2019. © Stefan Lux/MAK

Vienna-based design studio Eoos (Martin Bergmann, Gernot Bohmann and Harold Gruendl) have condensed the subject of climate change into five palatable projects. ‘The transition from the current world-destroying lifestyle to a future-proof, sustainable one is not only a question of design, but also of a participative society,’ says Gruendl, who advocates a ‘circular economy’, whereby waste is minimised. Their projects are speculative, but some look only a few tweaks away from the production line.

As a culture, we’re all too familiar with technology designed to fail. Greenfreeze 2 (2019), a sleek modular fridge with detachable components, seeks to defy the idea that if one part breaks, the entire appliance must be binned.

Installation view of ‘CLIMATE CHANGE! From Mass Consumption to a Sustainable Quality Society’. Pictured, SOV, by Eoos, 2019. © Stefan Lux/MAK

Aware that transport is one of the key culprits of climate change, Eoos developed their lightweight electric vehicle SOV (Social Vehicle, 2018), which consumes one tenth of the resources guzzled up by the average medium-sized car. Its most impressive trick is positioning itself – like a heliostat – towards direct sunlight to recharge.

Meanwhile, Kitchen-Cow (2019) turns food waste into heat. On its worktop, a funnel gobbles food waste into a glass ‘belly’, which ferments to produce biogas and comes full circle as fuel for the hob.

Kitchen-Cow, by Eoos, 2019, on show at ‘CLIMATE CHANGE! From Mass Consumption to a Sustainable Quality Society’.

Eoos’ Lunar Lander (2018) looks like a prop from a Stanley Kubrick film and makes use of an unorthodox fuel source: the microbes found in human urine. In practice, if every visitor to this year’s Donauinselfest music festival in Vienna used the Lunar Lander loo, it could generate enough electricity for a 30-million hour phone call.

Thanks to some unfavourable press, Artificial Intelligence has become synonymous with anxieties over job loss, androids overthrowing humanity, and downright confusion. How can we bin its Frankenstein’s monster reputation, and make meaningful use of its skillset? The exhibition ‘Uncanny Values: Artificial Intelligence and You’, curated by Paul Feigelfeld and Marlies Wirth, explains the past, present and future of how AI can infiltrate society, touching on themes from fake news to product design.

Lunar Lander, by Eoos, 2018 on show at ‘CLIMATE CHANGE! From Mass Consumption to a Sustainable Quality Society’.

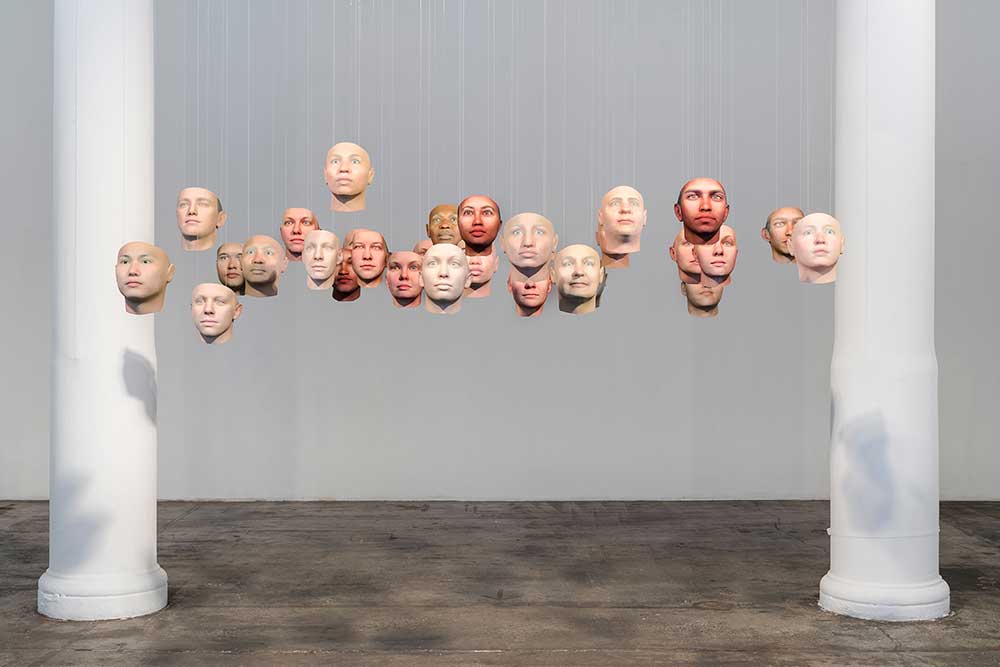

In 1970, Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori coined the term ‘uncanny valley’ to describe robots made with such an uncannily human interface that it induced both fascination and terror. Artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s Probably Chelsea (2017) does just that. Thirty 3D-printed versions of American whistleblower Chelsea Manning’s face hover over the exhibition on strings. But these aren’t Manning’s face as we know it. Using a single hair sample, these algorithmically generated masks eerily explain how the same strand of DNA could have culminated in different genders, ethnic backgrounds and bone structures.

Product designers Philipp Schmitt and Steffen Weiss have shaken up the traditional roles of human and machine. Their project, Four Classics (2019) sees eccentric twists on classical seating made with an AI designer and a human maker.

Probably Chelsea, by Heather Dewey-Hagborg and Chelsea E. Manning, 2017, on show at ‘UNCANNY VALUES: Artificial Intelligence & You’. Courtesy of the artist and Fridman Gallery, New York

Over the last two decades, digitalisation has reconfigured the requirements for living spaces, and expectations for sustainability in construction have escalated. ‘Space and Experience: Architecture for Better Living’, designed by Tzou Lubroth Architects and curated by Nicole Stoecklmayr, presents ten international architecture and design firms tackling these demands.

In this exhibition, algae seems to be the dernier cri. A large 3D-printed prototype, H.O.R.T.U.S. XL Astaxanthin.g (2019) by London-based architecture office EcoLogicStudio illustrates the capabilities of blue algae as a self-sufficient architectural material. As the algae grow, photosynthesis generates oxygen and biomass for building materials.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

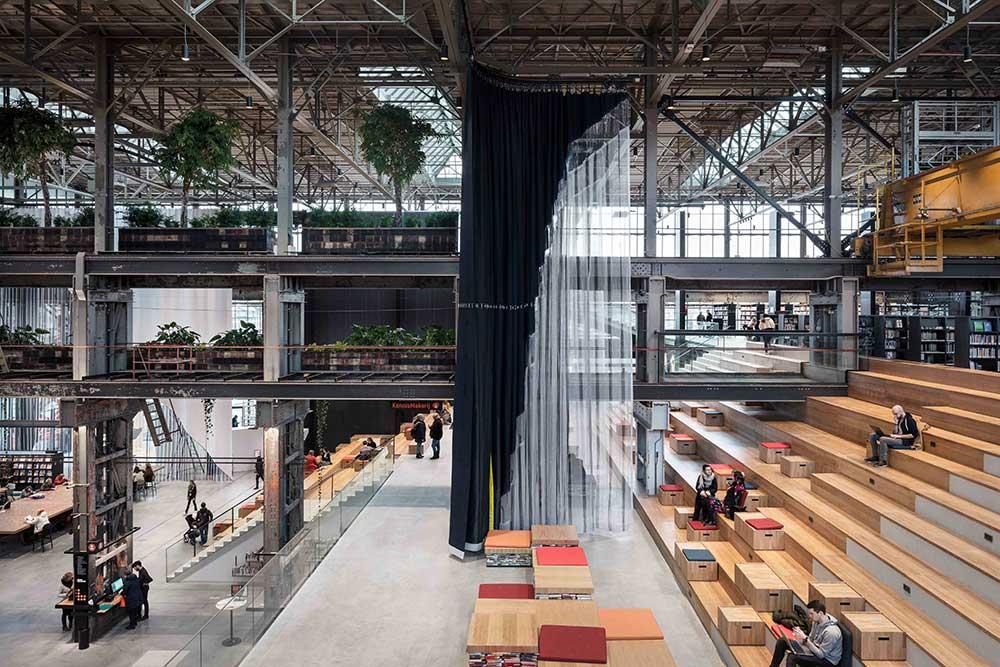

Their Photo.Synth.Etica (2018) is an ‘urban curtain’ of microalgae that can be draped over building façades to sap up air pollution. Other projects include Rotterdam-based MVRDV’s Seoul Skygarden (2017); a 1970s overpass turned horticultural haven, and Civic Architects’ LocHal (2019) – part co-working space, part exhibition hall.

The Chair Project (Four Classics), by Philipp Schmitt and Steffen Weiss, 2019, on show at ‘UNCANNY VALUES: Artificial Intelligence & You’.

The Vienna Biennale puts raw data in visual context, clarifies the blurs in public discussion and finds altogether more exciting ways of approaching these issues. So how should we view our digital future? The Biennale suggests that while utopian ideals can offer hope, dystopian fear can also help generate momentum for change. Perhaps we need both to forge a path for much needed revolution.

Installation view of H.O.R.T.U.S. XL Astaxanthin.g, by EcoLogicStudio (Claudia Pasquero and Marco Poletto), 2019 at ‘SPACE AND EXPERIENCE: Architecture for Better Living’.

LocHal, Tilburg (NL), by Civic Architects (Gert Kwekkeboom, Ingrid van der Heijden, Jan Lebbink, Rick ten Doeschate), 2019, on show at ‘SPACE AND EXPERIENCE: Architecture for Better Living’.

INFORMATION

Vienna Biennale for Change is on view until 6 October. For more information, visit the website

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.