Oscar Niemeyer: a guide to the Brazilian modernist, from big hits to lesser-known gems

Architecture master Oscar Niemeyer defined 20th-century architecture and is synonymous with Brazilian modernism; our ultimate guide explores his work, from lesser-known schemes to his big hits; and we revisit a check-in with the man himself

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012), who died just a few days before his 105th birthday, had been one of the last living links to the first years of modernist architecture, a social idealist and unabashed aesthete whose career spanned seven decades. Since his first works in the late 1930s, Niemeyer had gone from being Brazil’s most exalted architect to voluntary exile and then back again. He is undoubtedly the world's most influential Brazilian designer, an architect who has never shied away from modernism's political roots, imbuing his sculpturally dramatic schemes with both symbolism and social purpose.

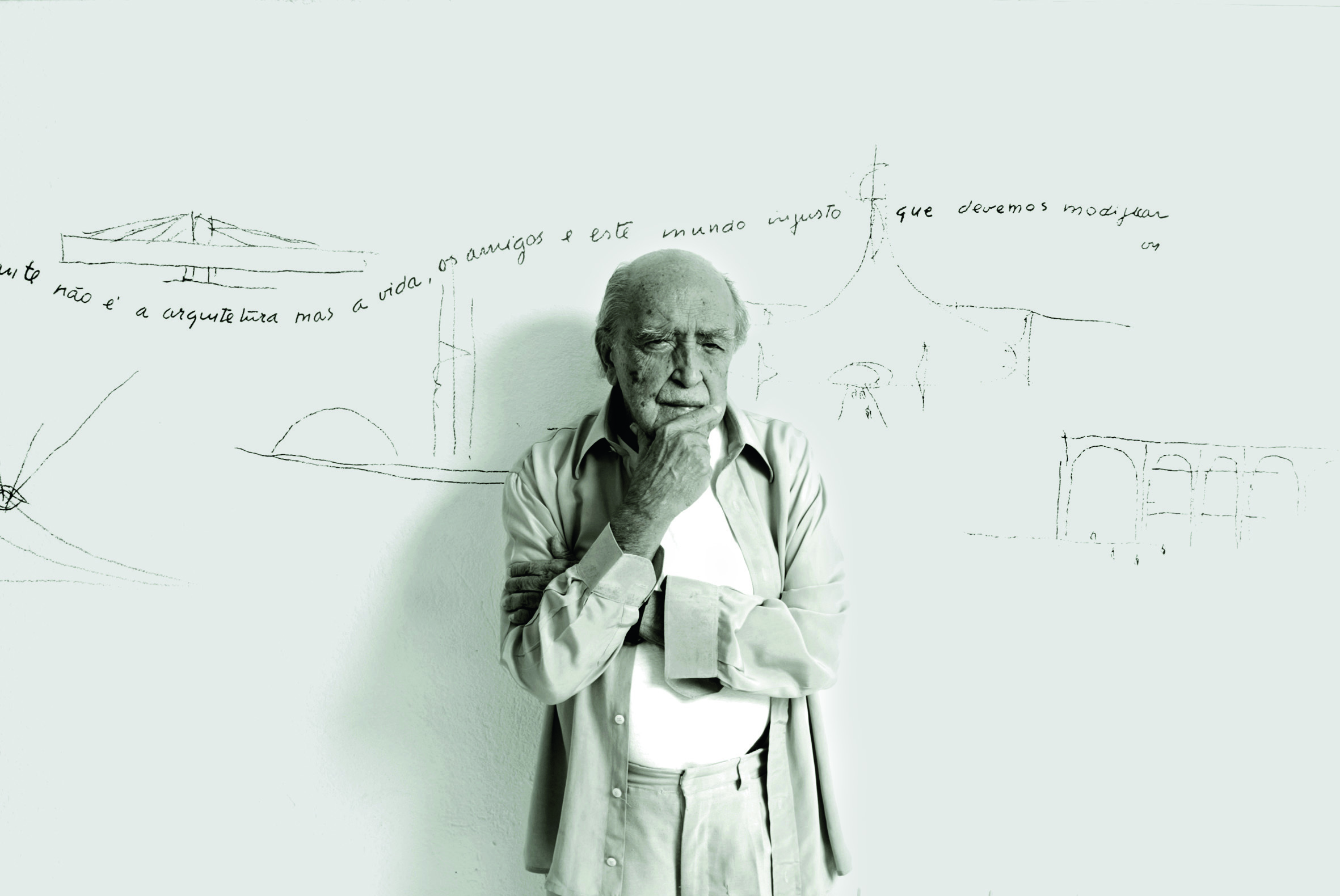

Oscar Niemeyer, photographed in his Copacabana studio in 2010 by Camilia Maia, and featured in our Born in Brazil issue (June 2010), where the Wallpaper* team dedicated the entire issue to reporting from the South American country

Entering the world of Oscar Niemeyer

Born and raised in Rio de Janeiro, where his practice continues to operate to this day, Niemeyer was prolific. His work, such as the Ravello auditorium in Italy, the Cathedral of Brasilia, the country's National Congress and the National Theatre, his prefabricated schools across Brazil, his complex at Ibirapuera Park in São Paulo and his Cultural Centre at Goiania – awarded Best Public Building in the Wallpaper* Design Awards 2007 – was immensely influential globally, defined 20th century Brazilian architecture, and frequently graced the pages of Wallpaper*.

Although initially he was strongly wedded to the formal simplicity of early modernism, it didn't take long for Niemeyer to find his own path, taking inspiration from the winding coastline, bold colours and sensual delights of his home town of Rio.

The history of an icon

Modern architecture's arrival in Brazil is usually carbon-dated to the Casa Modernista of 1928, built in São Paulo by Russian architect Gregori Warchavchik, who had moved to the country in 1923. In 1929, Le Corbusier undertook a South American lecture tour, returning to Brazil in 1936 to work on the Ministry of Education and Health Building in Rio, in collaboration with Lucio Costa and a team of young architects, including Niemeyer, Carlos Leao, Affonso Reidy, Jorge Moreira and Ernani Vasconcelos.

Widely acclaimed as the fount of the new Brazilian architecture, the building took European modernism as a starting point and presaged the Brazilian genre's move into free-form, concrete-fuelled exoticism. It wasn't to everyone's taste, not least the diehard modernists. The Bauhaus-trained Swiss functionalist Max Bill described Brazil's architecture as having 'thick pilotis, thin pilotis, pilotis of whimsical shapes lacking any structural rhyme or reason, disposed all over the place... works born of a spirit devoid of decency'.

Niemeyer's Tancredo Neves CIEP school in Rio, with its original distinctive oval windows, painted the colours of the Brazilian flag

Brazil embraced the new without reservation, remodelling its cities at the expense of many colonial-era structures. Niemeyer's own practice started small. His very first building was completed in 1937, while he was still working in Costa's studio and drawing inspiration from Le Corbusier. Modest in scale, traditionally modern in form, the Obra do Berço nursery is located in Rio's Lagoa, a prime neighbourhood beside the Rodrigo de Freitas lagoon. Le Corbusian in outlook, the nursery building conformed to the Swiss architect's famous five points: elevated up on pilotis, with a free plan, free façade, long runs of windows and a roof terrace.

Initially designed as a medical centre for expectant mothers, it now functions as both residential and day care for young children. The three-storey block is arranged around a north-facing courtyard with a generous roof garden and a large top-floor lounge above consultation rooms, clinics and wards. The west façade is shielded by a system of adjustable brise-soleils, allegedly reinstalled at the young architect's own cost after the initial fixed sun screens were built incorrectly.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Located on Rua Cicero G6is Monteiro in the Lagoa neighbourhood of Rio, Niemeyer's Obra do Berço nursery features vertical brise-soleils inspired by Le Corbusier

It was Niemeyer's turn to travel in 1939, when he and Costa set out to study and work in New York, ostensibly to design the national pavilion for the New York World's Fair of 1939-40, but also to soak up the delirious modernity of the city. While works like the Obra do Berço owed much to the boxy white purism coming out of Europe, the strictly functional approach never gelled with the Brazilian climate and culture, and a more organic, plastic modernism emerged. As the century progressed, the nexus of Brazilian modernism shifted even further from its origins. American modernism had hit the big time as a hyper-efficient tool of capitalism and mass consumption, while the Brazilian model, led by Niemeyer's poetic utopianism, was always more socially considered and less afraid of expression for expression's sake.

Brazil's official ideology was now diametrically opposed to Niemeyer's inherently leftist sympathies. By 1966, his position in Rio had become untenable, and Niemeyer decamped to Paris, setting up a studio on the Champs-Élysées, finding fresh work around Europe, Africa and the Far East, and designing architectural bentwood and leather furniture for the Japanese manufacturer Tendo and for Mobilier International. However, work in Brazil hadn't completely evaporated.

Completed in 1972, the Hotel Nacional tower is in Rio's São Conrado district. lt stood empty for many years – as seen here – after the hotel went bankrupt in 1995, but in 2017 it reopened as a luxury resort

In the late 1960s, Niemeyer undertook a commission for a new hotel in Rio's upscale district of São Conrado. Intent on preserving as much of the open space as possible, the design placed guest rooms in a 108m tall cylindrical tower set atop a concrete base and gardens landscaped by Roberto Burle Marx, an old collaborator of Niemeyer's. The Hotel Nacional opened in 1972 at the height of the military regime, its 510 rooms and convention centre surrounded by a sculptural landscape of concrete and greenery.

At the hotel's peak was an observation deck, she entered beneath a thick canopy of rain-streaked concrete and provided 360-degree views of the city, the sea and the mountains. The prominent site is now on Avenida Niemeyer, a coastal route that snakes its way south of the city past favelas, rocky coastline and the beach, the last forming the raw ingredients of Niemeyer's lifelong visual homage to the elements. The original hotel went bankrupt in 1995, and the building was abandoned, standing empty for many years – a brooding, concrete-topped, dark glass pillar, rising from the jungle at its base. It was not until 2017 that Hotel Nacional reopened, initially run by Mélia Hotels International, and now owned by private investors.

In 2022, Swiss watch brand Audemars Piguet invited a deconstructivist Athenian contemporary artist, Andreas Angelidakis, to exhibit in Paris’ communist party HQ, a building designed by Niemeyer while under protest exile in France. The HQ was inaugurated in 1971, and its dome completed in 1980

Niemeyer's political allegiances also came to the fore on his return to prominence. In the early 1980s, he was appointed by Leonel Brizola, governor of Rio de Janeiro state, to design a low-cost system for building schools. Brizola, with renowned anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro, proposed the creation of the Integrated Centres for Public Education, or CIEP, intended to bolster the number of schools in Rio's poorest regions, keeping children in education longer and providing facilities where nothing had previously existed.

Nakedly political in its aspirations, the CIEP programme used buildings made up of prefabricated concrete modules, while the teaching programme was specially developed and separate from existing public schools. There were problems; the project fell short of its initial targets, the large number of schools required ate through the budget, and teachers struggled to deal with the expansive classrooms.

Photographer Todd Eberle, left, with Niemeyer, right, for a shoot at Canoes House, near Rio de Janeiro in 2003. Then aged 96, Niemeyer travelled the almost hour-long journey from Rio to the home he'd designed for himself in the early 1950s, especially for Todd Eberle to take his portrait.

Eberle promised he'd take the shot in 'one minute'. He then quickly got a frame of himself with The Master. Considered one of the most significant and influential examples of modern architecture in Brazil, the house’s design infuses curves into concrete and glass

Nevertheless, the schools, located close to main roads and boasting distinctive concrete façades, were a statement of intent. Each school used a template of three structures: a main building housing classrooms and a cafeteria, a gymnasium that doubled up as a cultural centre, and a library with additional residential accommodation. The very first school, the CIEP Tancredo Neves in Catete, Rio de Janeiro, is still standing.

Completed in 1983, the building is robust and modest despite its scale. The massive prefabrication job was farmed out to private engineering companies, with up to 300 cubic metres of concrete a day being poured into slabs. At full tilt, a single factory could produce enough parts for one and a half schools a week. Although the CIEP school programme never garnered the global acclaim of his work in Brasilia or his cultural projects in Rio, the mix of concrete and political principles is a core component of Niemeyer's career.

Part of Todd Eberle's photographic portfolio, Itamaraty Palace, Brasilia. This gravity- and safety-defying staircase is one of the centrepieces of Brazil's Ministry of External Relations, an elegant pavilion surrounded by a pool and Roberto Burle Marx gardens

Niemeyer’s role in shaping the new Brazil is well chronicled. Together with Costa, he designed Brasilia, a project which contributed significantly to his expansive opus of over 500 buildings. The extraordinary range of Niemeyer's aesthetic is demonstrated time and time again, with his later works, in particular, showing a strongly symbolic sensibility, long before the fashion for iconic cultural statements gripped the world's cities.

His influence on the country's architecture is still strongly felt, and his longevity means that most of Brazil's practitioners are still subconsciously playing second fiddle. His body of work stands as an enormous achievement, instilling a great sense of pride in all generations of Brazilian architects and forming the bedrock of a design scene with a modern sensibility quite unlike that of any other country.

Oscar Niemeyer's Centro Cultural Oscar Niemeyer, Golania, Brazil, which won Best Public Space in the 2007 Wallpaper* Design Awards

9 key Niemeyer buildings

Edifício Copan

Copan, photographed as part of Todd Eberle's portfolio

Where: São Paulo

When: 1966

Niemeyer is known for his sweeping curves and organic shapes, and the large-scale application of this approach on Edifício Copan, a multi-family housing scheme in São Paulo, is emblematic of his work. Impressive yet soft, spanning 32 floors and 1,160 apartments, there is nothing 'boutique' about this project – apart of course from the bespoke architecture, which has made it into history books.

Ibirapuera Auditorium

Where: São Paulo

When: 2002

Oscar Niemeyer and landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx worked together on Ibirapuera Park, one of the most famous green lungs in São Paulo. Niemeyer's contribution includes the Ibirapuera Auditorium, a striking, for its crisp minimalism, volume defined by a single sloped shape, and a vibrant red coloured entrance whose door appears peeled off and floating in the wind above it.

Niterói Contemporary Art Museum

Niteroi Contemporary Art Museum, as part of Eberle's portfolio

Where: Niterói

When: 1996

The striking Niterói Contemporary Art Museum (Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói – MAC) is one of Niemeyer's later works, completed in 1996. Created with the help of structural engineer Bruno Contarini, the building's main body looks like a flying saucer, hovering high up from the ground and overlooking its coastal site.

Palácio do Planalto

The Palace shot by Paul Clemence, and featured as part of our story on Brasilia's 60th anniversary in 2020

Where: Brasília

When: 1960

If Palácio da Alvorada is where the President of Brazil lives, Palácio do Planalto is where he works. The office building is one of Brasilia's biggest landmarks – for its function as well as its striking modernist looks. It is an official part of the Brasília World Heritage Site, as designated by Unesco in 1987.

Palácio da Alvorada

Shot by Vincent Fournier for his book, Brasília: A Time Capsule

Where: Brasília

When: 1958

Palácio da Alvorada is the official residence of the Brazilian president. Surrounded by water, it sits on a peninsula by Paranoá Lake. The structure looks low and linear but comprises three levels, and beyond the residential wing, it also includes majestic reception spaces for special events and state entertaining.

National Congress of Brazil

The National Congress building as documented through the lens of artist and photographer Vincent Fournier and his book, Brasília: A Time Capsule

Where: Brasília

When: 1960

The powerful geometries of the National Congress building include a semi-sphere on the left, hosting the seat of the Senate, and a semi-sphere on the right, where the seat of the Chamber of Deputies lies. Two vertical towers between these two elements add drama and monumentality to this modernist design.

Cathedral of Brasília

Brasilia's cathedral, part of Todd Eberle's portfolio shown in Wallpaper* in 2013

Where: Brasília

When: completed 1970

The Roman Catholic cathedral of Brazil's newly – at the time – inaugurated capital, Brasilia, features a Niemeyer design, coming to life with some powerful engineering gymnastics by Brazilian structural engineer Joaquim Cardozo. The hyperboloid lines of the structure were constructed from 16 concrete columns.

United Nations Headquarters

Where: New York

When: 1952

Another result of teamwork in Niemeyer's portfolio is the iconic United Nations headquarters in new York. Ten architects and numerous consultants are credited for its inception, which dates back to January 1947. The ten architects were ND Bassov (Soviet Union), Gaston Brunfaut (Belgium), Ernest Cormier (Canada), Charles Le Corbusier (France) Su-Ch’eng Liang (China), Sven Markelius (Sweden), Oscar Niemeyer (Brazil), Howard Robertson (United Kingdom), GA Soilleux (Australia), and Julio Vilamajo (Uruguay).

Church of Saint Francis of Assisi, Pampulha

Where: Belo Horizonte

When: 1943

The mesmerising curves of the Church of Saint Francis of Assisi in Pampulha are a Niemeyer hallmark. Its completion in 1943 was accompanied by an interior mural by Candido Portinari, while the site also features landscaping by Roberto Burle Marx.

Interviewing Oscar Niemeyer at 102, in 2010

Wallpaper*: Your work is always immediately associated with Brazil. How 'Brazilian' do you consider your buildings to be?

Oscar Niemeyer: Modern architecture adopts a more international language, maybe in a more emphatic manner than it has ever occurred in any other period of architecture history. However, Brazilian culture is very powerful and is present in the imagination of the architects of this country. I believe I have not strayed too far from that: in Brasilia, Palácio da Alvorada suggests elements from our past: the horizontal direction of the façade, a large porch, a small church that, at the end of the composition, reminds us of our old farm villas.

W*: We are looking at Brazil at what seems to be a time of optimism, with the Olympics approaching in 2016; what opportunities do you see, what should the country make the most of?

Niemeyer: I believe that the whole country, particularly the civil construction and tourism industries, should make the most of the proximity of the Olympic Games.

To celebrate the life and legacy of Niemeyer, Wallpaper* produced a 28-page tribute to the architect, showcasing photographer Todd Eberle's images, to go with our February 2013 issue

W*: Which commission do you consider to be a key project in your career?

Niemeyer: The most important project for my career was the buildings I created for Pampulha, commissioned by Juscelino Kubitschek when he was mayor of Belo Horizonte. In those works, particularly in the small church and Casa do Baile restaurant, the visual vocabulary of my architecture started to define itself. Those large curved coverings started to descend in straight lines, in a surprising manner, thus conferring them with a different character that was justifiable through the issue of their structural forces. In other instances, they unfolded through repeated unpredictable curves created by my architect's imagination; it was on paper, when I sketched those works, that I made my protest against all rationalist, boring, barely inventive architecture, which had quickly spread from the United States to Japan.

W*: Some of your projects, such as the CIEP schools, are not as well-known outside Brazil as larger works like Brasilia or Pampulha. What role have slightly lower-profile projects like these played in your career?

Niemeyer: The CIEP schools in Rio de Janeiro are prefab public schools and, to me, the most important character of those schools is not their architecture; rather, it is the idea championed by my dear friend Darcy Ribeiro that children should stay in school all day long, where they should be provided with sports facilities and libraries, as well as some quiet spaces, crucial for their studies, which are often lacking in their homes. Regarding architecture itself, I sought, even with prefabs, to create structures that would be unique to them, so that they stand out among neighbouring buildings, thus ensuring they show the importance of the venture.

Latin America Memorial, São Paulo

W*: Your office is still working at full speed, and a few members of your family are also architects; how important is it for you that your work and firm are supported and continued by family?

Niemeyer: In my office, I am the only architect responsible for creating initial projects. Two great-grandsons of mine work there; I delegate some project developments to them. They are young architects just starting their careers, which I consider promising.

W*: Are there any Brazilian architects whose work you follow?

Niemeyer: I cannot fail to answer this question: a Brazilian architect I follow is my friend João Filgueiras Lima, aka Lele. His talent and his competence justify my interest. Some of his projects were presented by Nosso Caminho cultural magazine, edited by me and my wife, Vera Niemeyer.

Sambodromo, Rio de Janeiro. A piece of frivolity, its concrete columns and structure stretched taut like a strutting dancer's limbs, the 1984 Sambodromo sits at the heart of Carnival

W*: Do you have a daily routine? Do you go to the office every day? What role does architecture play in your life?

Niemeyer: I do have a kind of routine. I wake up fairly early and try to be at the office around 10am. I invariably have scheduled appointments, but I always set aside some time to dedicate to my sketches, which is the essential base to creating my projects. I have lunch at about 12.30pm. During the afternoon, I dedicate a few hours to writing articles and working on Nosso Caminho. At the end of the afternoon, friends come to visit. I go back home and eat dinner around 7pm. Architecture still occupies considerable space in my life.

W*: What would you wish for the future of Brazilian architecture?

Niemeyer: That it always responds, in a creative manner, to technical and social progress. That its professionals rely on their creative intuition without being afraid of anything. Intuition is responsible for unveiling life's secrets, for understanding how human beings, these highly unprotected beings, are able to face their drama.

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).