Meet Carmen Portinho, the pioneering engineer who shaped Brazilian architecture

Carmen Portinho’s pioneering vision shaped Brazil’s social housing, museums and modernist identity. A new exhibition in Rio finally gives her work the recognition it deserves

You may not be instantly familiar with the name Carmen Portinho, yet her work stands out. Perched imperiously on the hill that gives it its name, the Pedregulho housing complex rises like a modernist temple. Its sumptuous, sinuous form cuts a dynamic figure against the otherwise endless urban sprawl of Rio de Janeiro's São Cristóvão neighbourhood.

Pedregulho’s undulating 260-meter-long main block curves elegantly along the contours of the landscape, creating a highlight of socially conscious architecture in Brazil, or the tropical modernist architecture equivalent of the Acropolis. Unprecedented for a social housing block, architect Affonso Reidy’s ambitious masterpiece is unlikely to be repeated.

Yet beyond the innovative design that is characteristic of Reidy’s work, it embodies something else: the revolutionary vision of engineer and urban planner Portinho, his partner until he passed in 1964. While Reidy received the plaudits for Pedregulho, it was his formidable partner who transformed Brazilian modernism from behind the scenes, challenging every assumption about how society could be shaped through its architecture.

Carmen Portinho at MAM Rio

Carmen Portinho and Affonso Reidy: a partnership that shaped Brazilian modernism

Portinho’s relationship with Reidy, from the 1940s to his passing in 1964, proved transformative for Brazilian architecture. While he provided visionary designs from his time studying in France, she was inspired in her role as the head of Rio’s Department for Popular Housing by the dramatic changes to social housing she witnessed being implemented in post-war England.

'What an amazing couple. They were talking about urbanism, architecture, engineering, and art in the living room. Dreaming of the changes they could bring about to Brazil,' says Jose Dos Guimaraens, assistant curator and researcher for an exhibition that seeks to shine the spotlight on Portinho’s remarkable career, currently on display at another of their marvellous achievements, the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro.

Their collaboration at Rio’s Department for Popular Housing challenged traditional notions of what was possible in the built environment, paving the way for Brazilian modernism and its remarkable synthesis of international principles with local conditions. Portinho’s technical expertise, managerial skill, political savvy and personal charisma were essential to transforming Reidy’s visionary designs into reality for thousands of working-class Brazilians.

Pedregulho: a masterpiece that redefined social housing

'Pedregulho was the masterpiece,' says Dos Guimaraens. '[With it] they are showing the poorest people in society that the government could give you the same house as a rich person.'

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Built between 1948 and 1960, Pedregulho represented a radical departure from conventional social housing. While most projects focused on maximising units at minimal cost, Portinho dared to imagine that Brazil's working-class deserved beauty, art, and community facilities typically reserved for the elite. The complex featured stunning azulejo tile murals by celebrated artist Candido Portinari and another mural for the school by Roberto Burle Marx.

Built for local government employees to put them within 30 minutes of their place of work, the complex was shaped with high-quality materials and came with comprehensive community facilities, including a school, health centre, swimming pool, and communal laundry designed to liberate women from household drudgery.

'If you compare Pedregulho with Parque Guinle by Lúcio Costa, Parque Guinle was built for the upper class in Rio. Even Parque Guinle doesn't have Portinari panels,' notes Dos Guimaraens, highlighting the social project's unprecedented quality.

Architecture as social transformation

This wasn't just architecture—it was social transformation and, importantly for the fiercely feminist Portinho, empowering women through design. In her time at the head of Rio's Department of Popular Housing, Portinho refused to compromise on quality, fighting for what she called 'living spaces, not just apartments.'

'The projects of the Department of Popular Housing were housing with various uses, not only the residence, but also schools, leisure, art,' explains Aline Siqueira, curator of the exhibition. 'A project like Pedregulho brought with it the idea that everything you need to live in this space, you can have moments of pleasure and leisure, and that is part of your home, it belongs to you, and society.'

The complex even came with a regulatory guide teaching residents how to live in modern spaces, reflecting the era's belief that architecture could educate, empowering women in their daily lives by reducing time lost to daily chores. Yet Pedregulho's revolutionary approach was both its triumph and limitation. The project's ambitious scope made it expensive and difficult to replicate at scale.

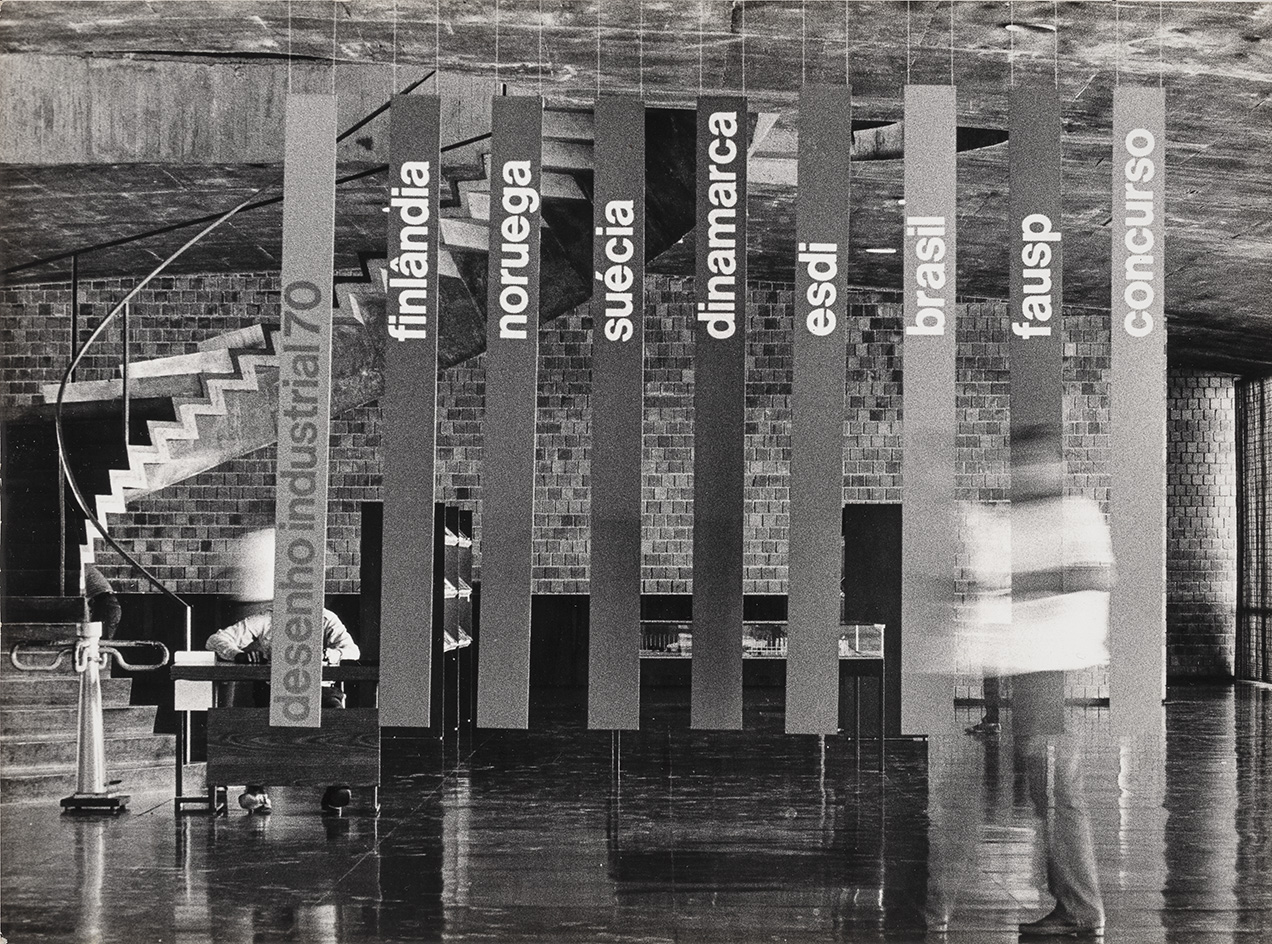

View of the exhibition Desenho industrial 70 at the Bienal Internacional do Rio de Janeiro, as part of Portinho's work, seen at the MAM Rio show

Only one other project similar in scope — the Minhocao of Gavea — was completed during Portinho’s time at the Department of Popular Housing. Two other projects, Vila Isabel and Paquetá, with similar lofty ambitions, were only partially completed. Even the weekend residence she shared with Reidy from 1952 was designed as a model home to be replicated by anyone who wished to build their own place into the steep terrain of Rio de Janeiro. Unfortunately, even though the designs were made available for anyone to use, nobody did.

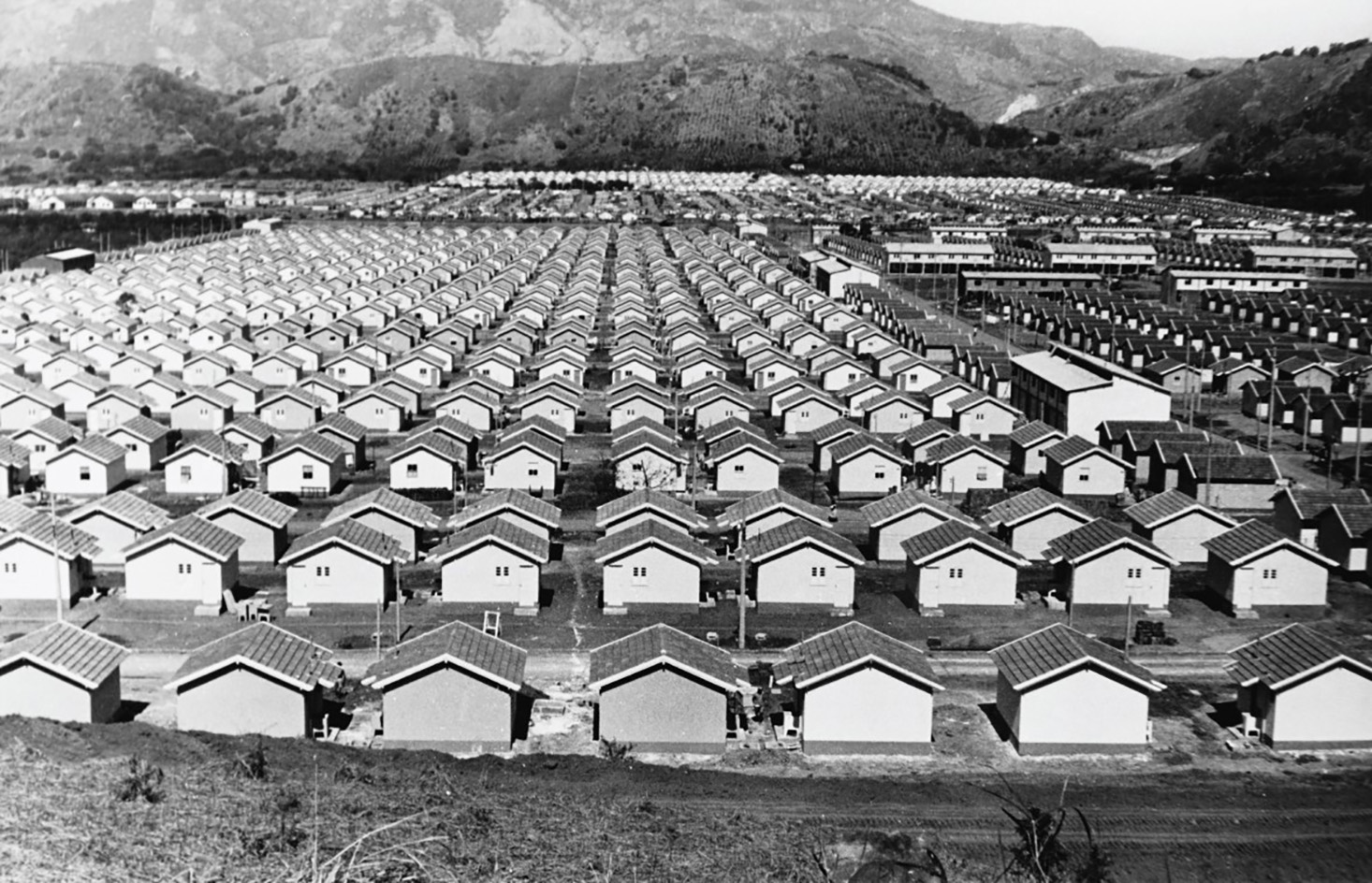

Portinho's optimistic vision for Brazilian social housing faded when faced with a political shift that meant Rio de Janeiro’s favelas we relocated to places like the Cidade da Deus suburb at around the same time as Pedregulho was being completed.

Participants at the Congresso Internacional Feminista on a trip at Recreio dos Bandeirantes - as seen in the MAM Rio exhibition

Building Brazil's cultural identity at MAM Rio

Dejected but unfaltering, Portinho went on to channel her energy to transform the fortunes of the Museum of Modern Art (MAM) in Rio de Janeiro. Joining as executive director in 1951, she worked alongside socialite Niomar Muniz Sodré. While her counterpart handled fundraising and cultivated social cachet with an international jet-set, Portinho managed daily operations and oversaw construction of the museum on reclaimed land adjacent to the Santos Dumont airport - fighting once again for the project to be designed by Reidy.

The revolutionary structure, Brazil’s first brutalist monument, was shaped entirely from concrete, paving the way for other familiar landmarks in other Brazilian cities, such as the Museu de Arte de Sao Paulo (MASP), designed by another cultured power couple, Lina Bo Bardi and Pietro Maria Bardi. Completed a decade before MASP, Reidy’s creation of democratic public space at MAM Rio unquestionably influenced Bo Bardi and many others.

Under Portinho’s leadership, MAM Rio became Brazil's most important art space in the 1950s and 1960s, and she helped organise exhibitions that brought Brazilian art to global attention, essentially curating the country's cultural identity on the world stage.

After leaving MAM Rio in 1966, Portinho continued with her passion for bringing art to everyone by introducing Brazilian contemporary art to the curriculum as director of the Superior School of Industrial Design. Throughout her career, she maintained that architecture and design could be vehicles for social change, democratizing access to beauty and quality.

Diplomatic genius in a male-dominated world

Portinho's unquestionable success is all the more remarkable given the male-dominated setting in which she operated. Born in 1903 and raised in a politically progressive household, she was just the third woman in Brazil to graduate as an engineer in 1925. In a workplace rife with machismo, her male colleagues challenged her to inspect a lightning rod atop city hall - expecting her to fail. Unknown to them, Portinho was an accomplished mountaineer who completed the task effortlessly, establishing a pattern of exceeding expectations that would be repeated in a lifetime spent breaking through glass ceilings.

'Carmen was very diplomatic,' observes Dos Guimaraens. 'And to be diplomatic, not confrontational, was a strategy.' This wasn't passive accommodation but calculated institutional change.

While male contemporaries often confronted systems head-on, Portinho understood that transformation required nuanced navigation of male-dominated spaces from within, argues Dos Guimaraens. She famously worked side-by-side with Bertha Lutz, the sister of her first husband and the founder of the Brazilian suffragette movement, to persuade President Getulio Vargas to give women the vote in 1932.

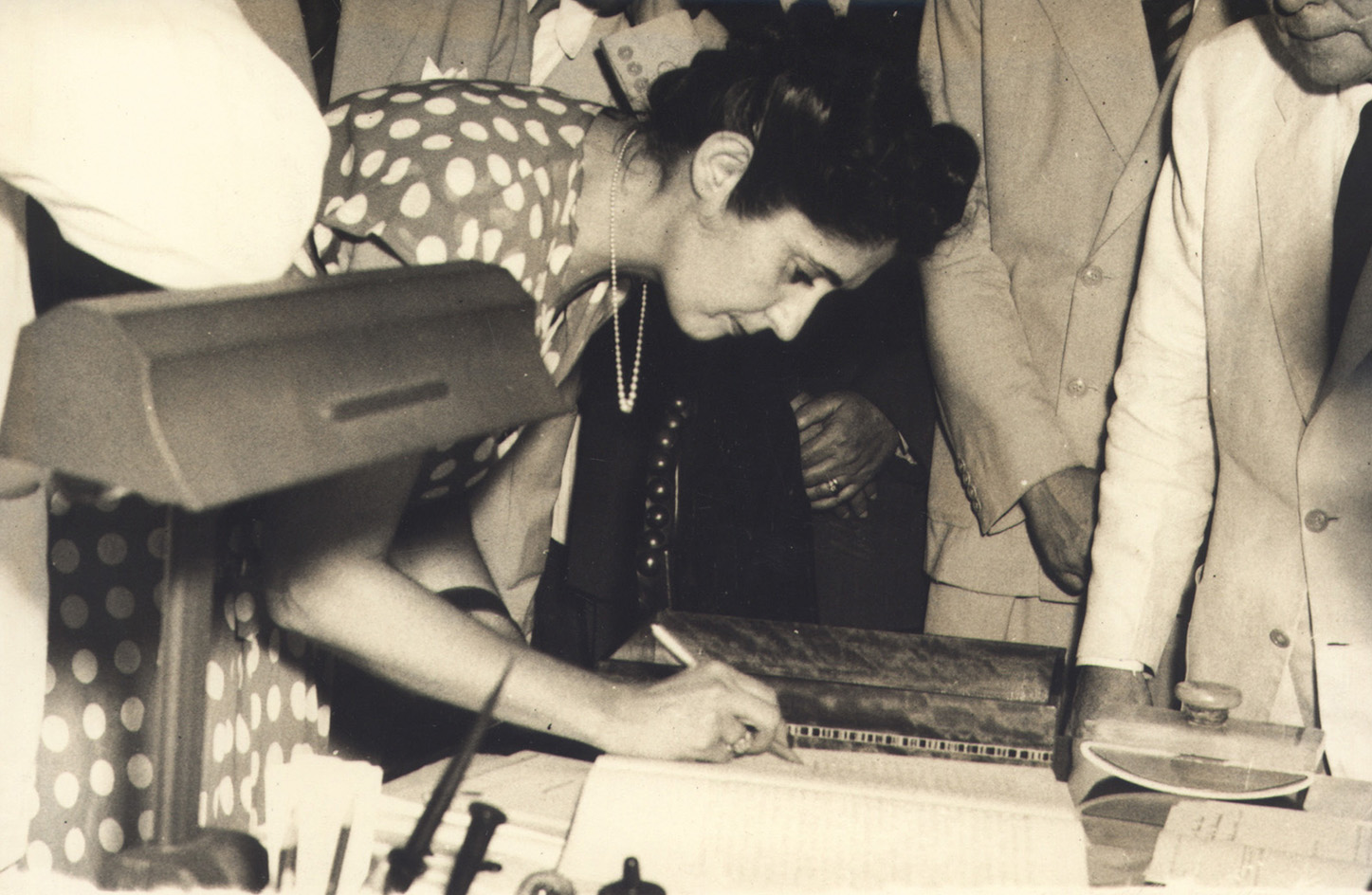

Carmen Portinho takes office as director of Departamento de Habitação Popular

A legacy that endures

Portinho's legacy continues to resonate today as cities worldwide grapple with housing crises and social inequality. Pedregulho's integration of community facilities, art, and thoughtful urban planning principles remains as relevant now as when it was conceived. Unlike many social housing projects that deteriorated into slums, the developments she championed maintained their quality and community pride over decades.

'People are really proud to live in these places because there's a lot of quality,' notes Dos Guimaraens, highlighting Portinho's enduring influence on how we think about dignified housing for all citizens.

Vila Kennedy, which received relocated residents from the favela in Praia do Pinto and other communities, one of the projects that led Carmen Portinho to resign from her position as the head of Rio's Department for Popular Housing

In an era of increasing housing precarity and social division, Carmen Portinho's vision offers a powerful counterpoint. The curved silhouettes and integrated communities in her projects remain not just architectural landmarks, but physical manifestations of the belief that the most disadvantaged citizens deserve the richest environments. Through diplomatic genius and unwavering commitment to quality, she rewrote Brazil's cultural narrative while proving that true revolution happens through persistent, strategic reimagination of what's possible.

Drone footage of Pedregulho by Andre Scarpa, with thanks to andrescarpa.com

'Carmen Portinho: Modernity in Construction' runs until March 2026 at MAM Rio, Brazil

Originally hailing from the UK, Rainbow Blue Nelson first landed in Colombia in search of Tintinesque adventures in 1996. Subsequent forays from his Caribbean base in Cartagena have thrown up a book about Pablo Escobar, and the Wallpaper* City Guides for Santiago, Brasilia, Bogota and Miami. Currently completing a second book about Colombia whilst re-wilding 50 hectares of tropical rainforest on the country's Caribbean coast, he’s interviewed some of South America's most influential figures in art, design and architecture for Wallpaper* and other international publications.

-

Winston Branch searches for colour and light in large-scale artworks in London

Winston Branch searches for colour and light in large-scale artworks in LondonWinston Branch returns to his roots in 'Out of the Calabash' at Goodman Gallery, London ,

-

The most anticipated hotel openings of 2026

The most anticipated hotel openings of 2026From landmark restorations to remote retreats, these are the hotel debuts shaping the year ahead

-

Is the future of beauty skincare you can wear? Sylva’s Tallulah Harlech thinks so

Is the future of beauty skincare you can wear? Sylva’s Tallulah Harlech thinks soThe stylist’s label, Sylva, comprises a tightly edited collection of pieces designed to complement the skin’s microbiome, made possible by rigorous technical innovation – something she thinks will be the future of both fashion and beauty

-

A spectacular new Brazilian house in Triângulo Mineiro revels in the luxury of space

A spectacular new Brazilian house in Triângulo Mineiro revels in the luxury of spaceCasa Muxarabi takes its name from the lattice walls that create ever-changing patterns of light across its generously scaled interiors

-

An exclusive look at Francis Kéré’s new library in Rio de Janeiro, the architect’s first project in South America

An exclusive look at Francis Kéré’s new library in Rio de Janeiro, the architect’s first project in South AmericaBiblioteca dos Saberes (The House of Wisdom) by Kéré Architecture is inspired by the 'tree of knowledge', and acts as a meeting point for different communities

-

A Brasília apartment harnesses the power of optical illusion

A Brasília apartment harnesses the power of optical illusionCoDa Arquitetura’s Moiré apartment in the Brazilian capital uses smart materials to create visual contrast and an artful welcome

-

Inspired by farmhouses, a Cunha residence unites cosy charm with contemporary Brazilian living

Inspired by farmhouses, a Cunha residence unites cosy charm with contemporary Brazilian livingWhen designing this home in Cunha, upstate São Paulo, architect Roberto Brotero wanted the structure to become 'part of the mountains, without disappearing into them'

-

Arts institution Pivô breathes new life into neglected Lina Bo Bardi building in Bahia

Arts institution Pivô breathes new life into neglected Lina Bo Bardi building in BahiaNon-profit cultural institution Pivô is reactivating a Lina Bo Bardi landmark in Salvador da Bahia in a bid to foster artistic dialogue and community engagement

-

Tropical gardens envelop this contemporary Brazilian home in São Paulo state

Tropical gardens envelop this contemporary Brazilian home in São Paulo stateIn the suburbs of Itupeva, Serena House by architects Padovani acts as a countryside refuge from the rush of city living

-

Itapororoca House blends seamlessly with Brazil’s lush coastal landscape

Itapororoca House blends seamlessly with Brazil’s lush coastal landscapeDesigned by Bloco Arquitetos, Itapororoca House is a treetop residence in Bahia, Brazil, offering a large wrap-around veranda to invite nature in

-

A postmodernist home reborn: we tour the British embassy in Brazil

A postmodernist home reborn: we tour the British embassy in BrazilWe tour the British Embassy in Brazil after its thorough renovation by Hersen Mendes Arquitetura, which breathes new life into a postmodernist structure within the country's famous modernist capital