Balkrishna Doshi exhibition opens at Vitra Design Museum

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

The first solo exhibition of architect Balkrishna Doshi’s work outside of Asia, has opened at Vitra Design Museum. Global interest in the Indian architect – who worked with Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn and brought modernism to India with his distinct philosophy – has soared since being named the 2018 Pritzker laureate. Yet, Mateo Kries, director of the museum, is keen to express that the show had been in planning since 2017 – Vitra was one step ahead.

So why in this year that also celebrates Bauhaus and Vitra Design Museum’s 30th anniversary is Doshi the architect of choice? A visit to the exhibition will make this clear – Doshi is a humanist whose philosophies on housing, education, sustainability and urbanism are still as urgent as when he started practicing architecture in the 1950s.

One of those priorities, that of the ‘home’, is close to Vitra’s heart: ‘Housing for Doshi is much more than creating walls and places for people to stay, housing for him is a philosophical place,’ says Kries. And here, at the home of Vitra – where design pieces are born with a respect for the past and a guarantee for the future and comfortable living environments are layered up at the VitraHaus – Doshi’s philosophy of ‘home’ is held up high with much esteem.

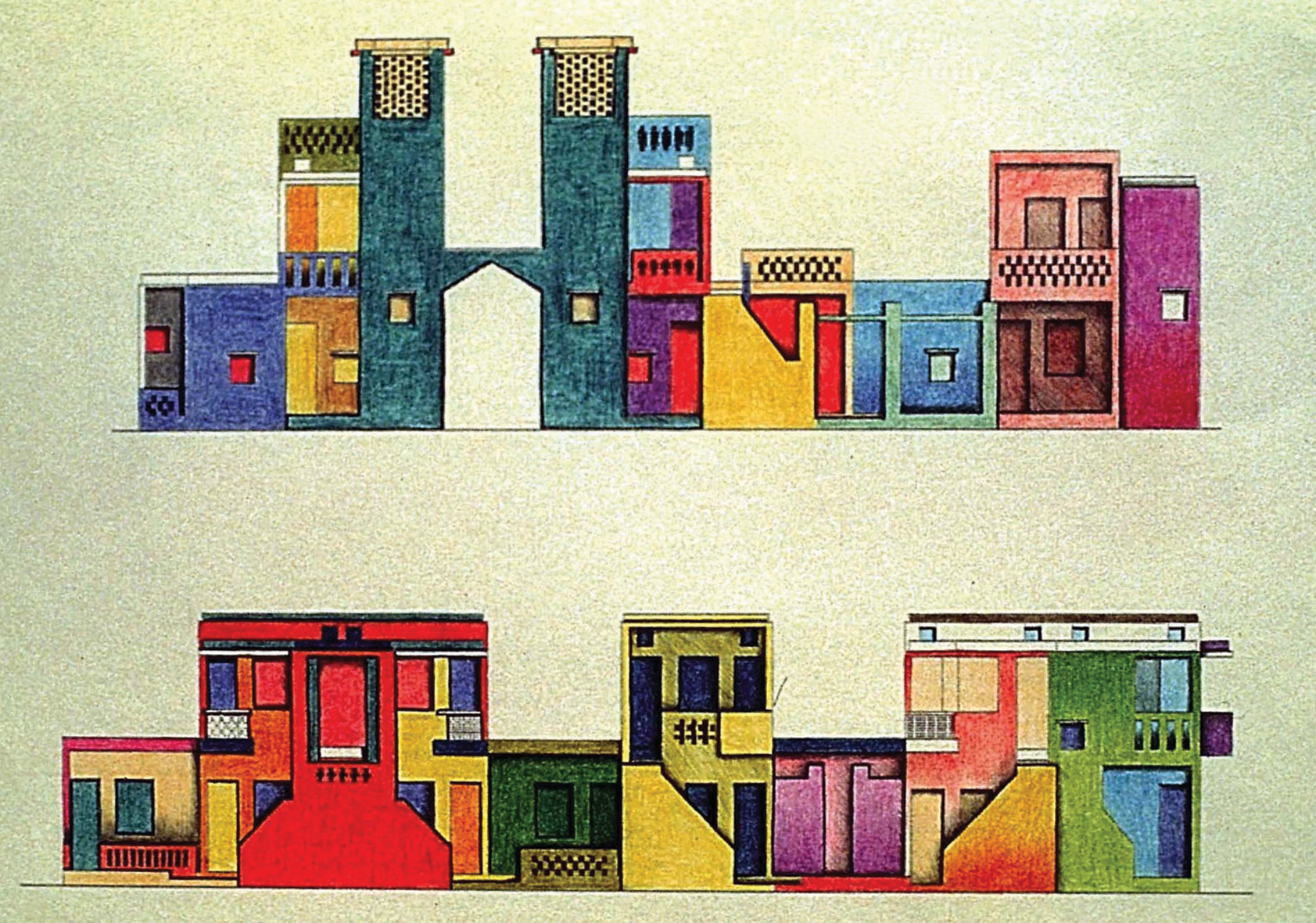

Housing for the Life Insurance Corporation of India, Ahmedabad, 1973

In his opening talk – so grossly over-subscribed that it relocates to a vast warehouse space on the Vitra campus – Doshi says: ‘Delight, joy, curiosity, that is how you create places, moulding these things in your mind. You have to think, what would I enjoy most?’ When he receives a commission from a client, he asks them about their family, their neighbours, what they do on Sunday. ‘Because everything we build, we build for human beings.’

A unique insight into the world of Doshi has been brought to the Vitra Design Museum by curator Kushnu Hoof, director of the Vastushipla Foundation – who is also Doshi’s grand-daughter. Alongside Jolanthe Kugler, Vitra Design Musem curator, Hoof adapted the exhibition from an exhibition of Doshi’s work at the Power Station of Art in Shanghai, and adding large-scale installations that offer visitors a spatial understanding of his work.

One of the installations represents the proportions of Doshi’s own home in Ahmedabad, Kamala House built in 1963. Here space is used modestly and democratically, something that his own house has in common with the housing projects he has designed for others.

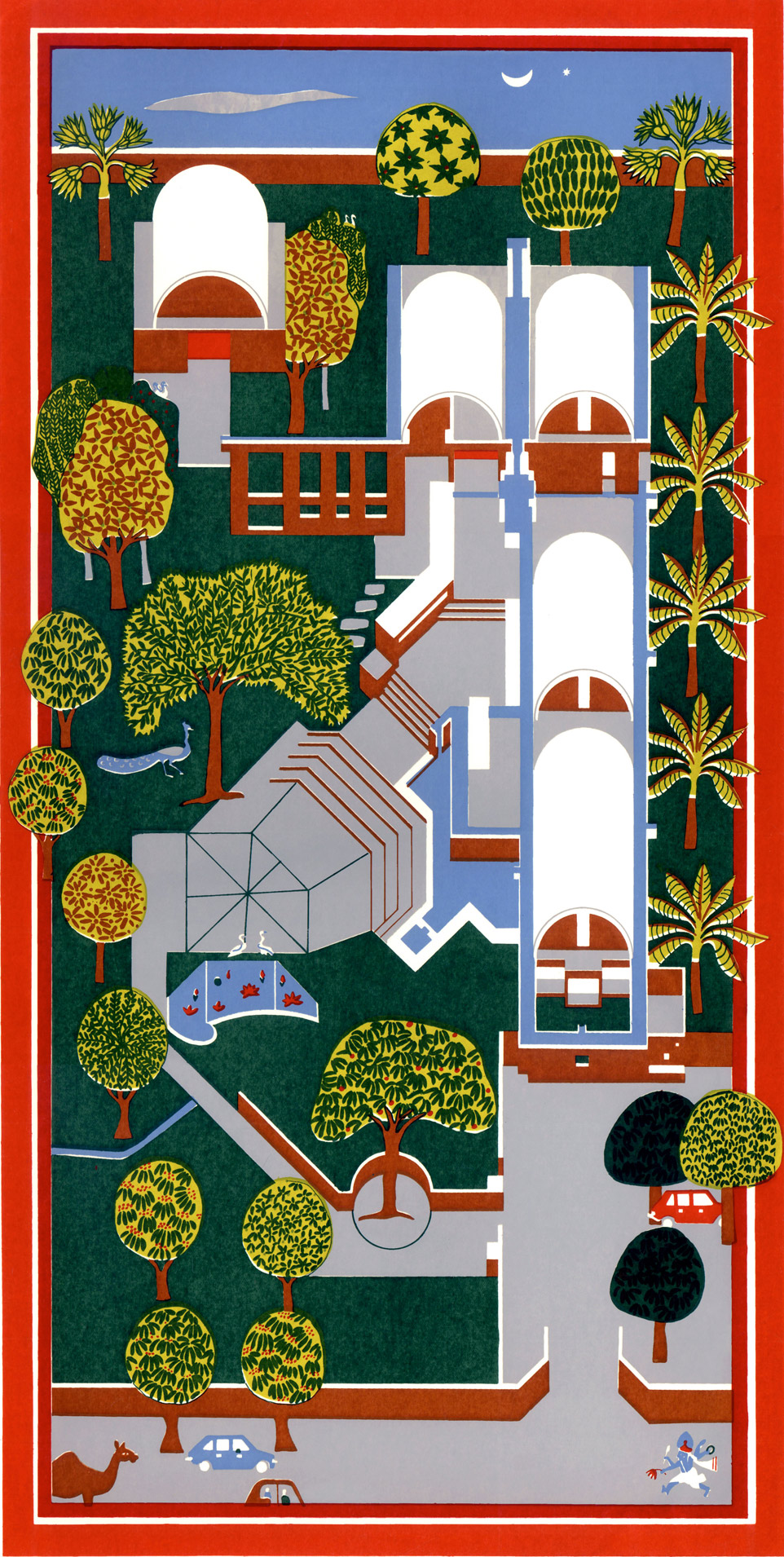

Sketch of the Aranya Low Cost Housing in Indore, 1989.

Whether it’s by blurring the lines of India’s caste system, driving the economy, or even just suggesting that everyone is equal, Doshi embeds democracy into his architecture. The housing for the Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC) in Ahmedabad (1973) integrates social groups together using stacked blocks, shared entrances and colour. While at the Aranya low cost housing project in Indore (1989) Doshi participated in designing a new model for economic growth by providing an infrastructure combined with ‘units’ supplied with the key elements of a plinth, electricity and toilet, to lower income families to build and adapt to their own needs.

Doshi learnt that there is no distinction between object and living from Le Corbusier, who he worked for on the Chandigarh project where ideas of life, urbanism, and modernism came together in India, where the climate and culture demanded something new from modernism. And from Louis Khan, Doshi learnt to make friends with his clients to be able to build what he wanted.

Wise advice no doubt on both accounts, yet Doshi has much to teach too. He says that the thing he taught Le Corbusier was naivety, and his own advice for designing is to be like a child, to look things in new ways and not be constricted by history and tradition.

RELATED STORY

The exhibition explores Doshi’s interest in education in depth. In 1968, he founded the School of Architecture at the Centre for Environment and Planning (CEPT) in Ahmedabad. Here he could define his own laws of architecture, and challenge students to think differently. Another large-scale installation is that of the art gallery Amdavad Ni Gufa built on the CEPT campus in 1994. Designed digitally and built by unskilled labourers, this ‘Gufa’ or cave has no foundations or walls and is covered in broken porcelain saucers salvaged from factory waste. Bubbling up from the exhibition floor, the structure asks us to re-evaluate everything we thought we knew about architecture.

Courtyard corridor at the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore, 1977, 1992.

Living organisms sprout across the walls of the exhibition too through architectural drawings, plans and photographs – from the mushrooming modules of the MPEB office campus in Japalpur (1979) to the lush plant-layered courtyards of the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore (1977), and at Sangath, his studio and oasis in Ahmedabad where his respect for nature can be seen in his mural to a mango tree that died. ‘Sangath is his own sanctuary, he’s put every experience he has ever has together into this,’ says Hoof.

Many of Doshi’s designs are modular, echoing ecological forms, yet also very practically providing the flexibility that was needed in India from the 1950s during a period of rapid post-Independence change – architecture had to be prepared for shifting contexts, it had to be self-perpetuating and ever-evolving like a city that takes into account of the chaos of change, creation and growth.

Inspired by the aesthetic and perspective of Indian miniatures where ‘space, activity and landscape are layered and you can see how the space feels through one singular image’, says Hoof, Doshi’s paintings, drawings and models are multi-dimensional, and full of life, combining architecture with a whole set of cultural philosophies.

Miniature painting of Sangath Architect’s Studio by Balkrishna Doshi, 1980.

Doshi is always thinking of the bigger picture, approaching architecture like urbanism: ‘When he made a project, he made a project for the area around it too, he was not looking at it in isolation, but of how to improve the life of the whole area,’ says Hoof.

‘I call architecture not a building, but a habitat, a living organism,’ says Doshi. And it is this approach that makes his work sustainable ‘in a wider sense, not just the narrow economical sense’ says Kries. When he designed the Premabhai Hall (1976) he later also designed an urban system for the whole Bhadra Plaza to connect all the main building podiums with pedestrian walkways; while the design for the Digambar Jain temple complex in Pune (2004, unbuilt) infilled the outer walls of the temple with apartments for employees to live.

‘Sustainability is comprehensive. When [architecture] is isolated then it is not sustainable. As an architect you have to think at macro scale. Why should we think architecture is only building? Are we building tombs that cannot grow?’ says Doshi. The exhibition carries many powerful lessons, such as this, that seem timeless – Doshi is now 92 years old and has been working over a period of 60 years – yet somehow, these lessons also seem increasingly urgent.

Kamala House, Ahmedabad, 1963, 1986. Ahmedabad

Installation view of the exhibition at the Vitra Design Museum

Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore, 1977, 1992.

Installation view of the exhibition at the Vitra Design Museum

Aranya Low Cost Housing, Indore, 1989.

Aranya Low Cost Housing, Indore, 1989

Lalbhai Dalpatbhai, Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad, 1962.

Premabhai Hall, Ahmedabad, 1976.

INFORMATION

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People’ is on view until 8 September 2019. For more information, visit the Vitra Design Museum website

ADDRESS

Vitra Design Museum

Charles-Eames-Straße 2

79576 Weil am Rhein

Germany

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.