Anupama Kundoo and the architecture of happiness

From craft-inspired baked kiln homes to comforting jali-walled classrooms, architect Anupama Kundoo explores groundbreaking techniques to design happiness-inducing buildings for every context. She talks with writer and trained architect Shumi Bose about design for contented living

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Ten years ago, Anupama Kundoo and I discussed the labels and descriptors that had thrown us together: female architect, Indian architect, architect of the Global South, architect working with traditional-slash-vernacular-slashregional-slash-‘indigenous’ techniques.

Each of these labels elicits a special appreciation of Kundoo’s work, while at the same time producing a particular kind of frustration – they constrain and diminish. At the time, she conceded to the description of lyrical modernist – for here is a practitioner driven to understand materiality, technology and capital utility, in the manner of the early modernists; how to maximise the efficiency of resource and labour, while at the same time providing a sense of joy, beauty and identity. For Kundoo, though, none of this would qualify her work as regional or vernacular. Rather, it is born of a wilfully objective assessment of resource and circumstance. ‘I don’t see happiness as something frivolous. There is no other aim: to be alive is to be happy. When we are not happy, it indicates that something in us is not alive.'

Anupama Kundoo, shot in February 2021 in Berlin.

From a broad portfolio of built works, two are particularly emblematic of Kundoo’s approach. An orphanage, or home for homeless children, built for the charity Volontariat in 2008, is one of her most photogenic projects, and is beloved by students as an example of unique but wholesome architecture. Developed with pioneering ceramicist Ray Meeker, individual building units were effectively designed as large-capacity kilns, which were themselves fired in situ to produce a sort of home-baked house. Modelled after catenary structures to provide maximum stability, the finished homes resemble mosaic molehills. Local artisans stuffed a great many ceramic objects – from building elements to handcrafts for sale – into the kiln houses, to be fired during the ‘baking’ process. As such, the project allowed the use of local materials while supporting artisanal production. The result is the emergence of a new building technology, which ennobles knowledge latent in the community.

While recalling its technical challenges with love and seriousness, Kundoo is a little tired of the attention garnered by the project’s appearance. But its visual appeal is instant and powerful; its unusual form and texture draw us in, while the production narrative explains the ethos of the project. Not only does the aesthetic of this building signify a different way of doing things, its construction and operation align graciously too, along with the decisive utility of both contemporary and traditional technologies. This quality is evident in much of Kundoo’s work – at once sublime and pragmatic.

Each of the Volontariat Home domes was fired while stuffed with raw ceramics, so the making of the home produced other goods simultaneously.

Kundoo’s own residence, Wall House (2000), also illustrates her experimentation with innovative techniques – such as the repurposing of artisan-made terracotta bowls, embedded in the ceiling to cut mass, regulate humidity, and enhance comfort, or the use of perforated ferrocement louvres. With typical intimacy, Kundoo exhibited fragments of Wall House as her debut at the Venice Architecture Biennale, in 2012, underlining that for her at least, real life and architectural inquiry are very much intertwined. Spectacular without being ostentatious, the collaboratively built installation recreated 1:1 fragments – memorably, a vaulted terracotta ceiling – from Wall House, inviting the visitor into lived space.

Her next offering at the Biennale, in 2016, was less poetic: a ferrocement house, buildable in less than a week. Rectilinear and visibly contemporary, the Full Fill Home doubled down on refined building technologies, and the promise of both utility and satisfaction. Kundoo denies any posturing loyalty to low-tech or ‘traditional’ methods, adhering to a holistic but essentially modern approach.

Bicycle wheels provided the formwork for windows at the Volontariat Home.

Kundoo’s philosophy has broadened and grown branches over a career spanning three decades. And she has had ample time to review that growth while preparing for a current exhibition at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark (until 16 May), a generous and tactile survey of her work so far. ‘Time’ recurs as a motif throughout, notably in ‘Taking Time’, Kundoo’s own short but inspiring essay written for the occasion. As Kundoo writes, the work of [an architect’s] lifetime is part of a large collective action in time and space. As such, it is essential to claim not only space but time too – puritanical ethics be damned. After all, ‘who are we to manage time?’ she says, laughingly. ‘Time is managed by the sun.’

Graduating from architecture school in 1989, Kundoo eschewed the frenetic pace of Bombay (as it was then) and gravitated towards rural South India. Based near the former French-Indian territory of Pondicherry (now Puducherry), she gave herself the permission to take time – a decade, no less – to develop her own agenda, away from the competitive commercial jobs sought by her peers.

These years were not spent idly; having established her own office at the age of 23, Kundoo applied herself to the collective intellectual and structural development of Auroville – a uniquely experimental town straddling Puducherry and Tamil Nadu, continuously in the making, and founded in 1968 ‘to realise human unity’. ‘I managed to find a way that I could just focus on proactivity, on positive action, rather than resisting and fighting against the grain; to manifest the opposite of some things, to actually build what I want the world to be.’

The Shah Houses in Brahmangarh, completed in 2003, combine locally available basalt with hollow terracotta tubes, made by local potters, for vaulted ceilings.

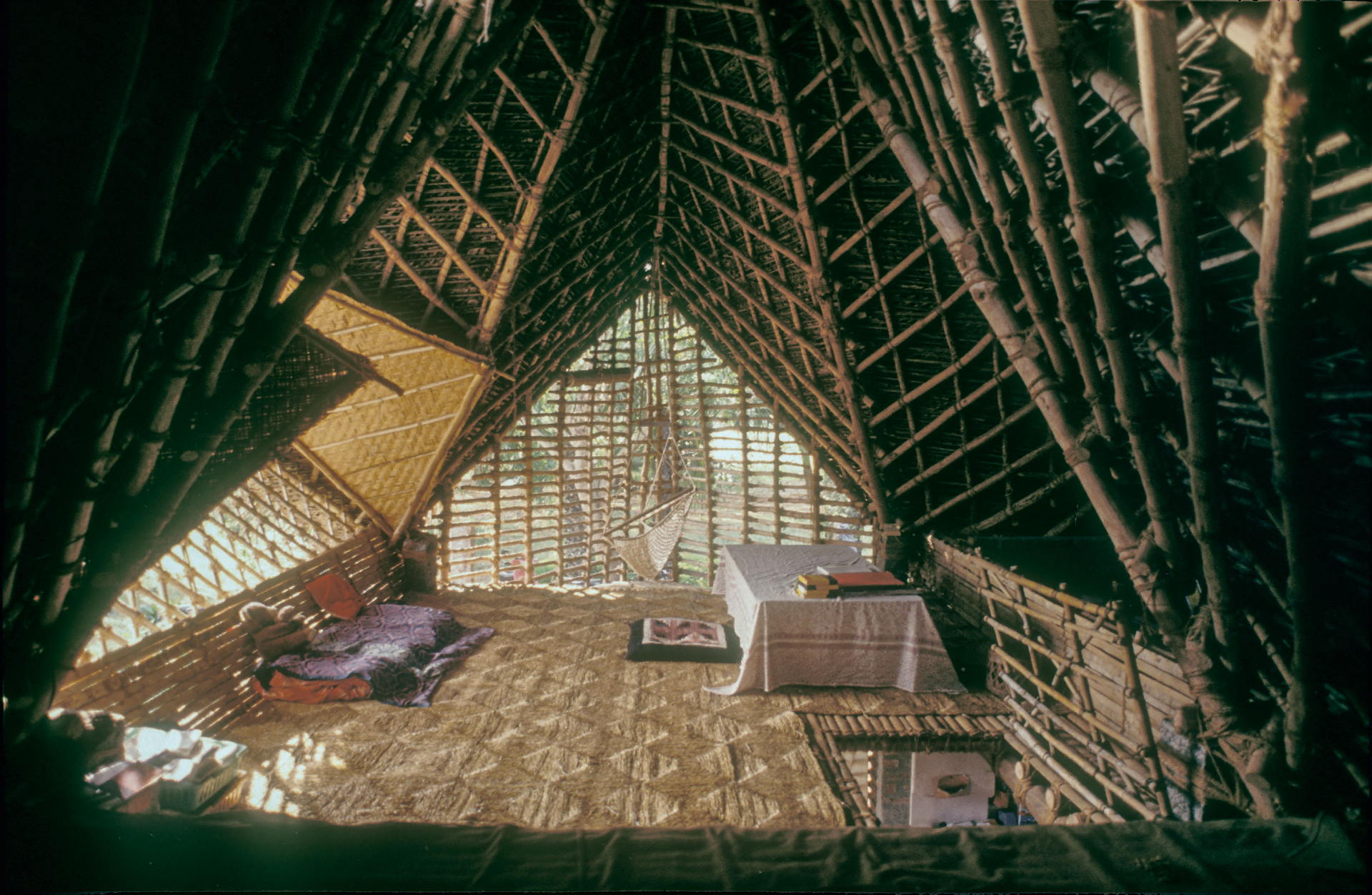

Kundoo’s experimental and resourceful approach began with the construction of her own humble residence in Auroville, the Hut in Petite Ferme (1990) – a thing of bravery and simplicity. The image is undeniably romantic: this barefoot architect goddess, riding around the lushness of Tamil Nadu on a motorbike, befriending local craftsmen and building from the heart, retiring to her hammock to dream up idealistic futures. But it happened, and the approach that it forged for Kundoo is anything but sentimental. Living in this engineered cobweb, with only slatted palm stems against the elements, Kundoo ran an office of some two dozen architects, producing ambitious experiments and radical techniques.

Combining modern materials with the skills of artisanal communities to meet climactic, ecological and socio-economic needs, the office tested the use of round wood, thatch and rammed earth alongside concrete and ferrocement; Kundoo estimates she completed 35 buildings during this time, each innovating and paving the way for future constructions.

She speaks with glee about taking time to do nothing, to contemplate the richness of doing nothing, to reject the oppression of productivity for its own sake. It’s hard to imagine where she has found the time to do nothing, given a prolific output, a string of teaching positions and research projects between Sydney, Madrid, Berlin and New York, and a slew of studies on sustainability.

In an interview with Martha Thorne, executive director of the Pritzker Prize, Kundoo deftly reframes the trifecta of practice, research and teaching as ‘function, mind and spirit’. The conversation prompts a confounding realisation: to date, Kundoo has never been recognised with an award, for her built work or her groundbreaking research – nor any of the special recognitions reserved for the still-marginalised categories of women and minority architects. More notably, her work has enabled unprecedented collaboration between students, architects, engineers and artisans, between hemispheres and across materials.

Wall House, Kundoo’s Auroville home completed in 2000 and revisited as an installation for the Venice Biennale in 2012. Repurposed terracotta bowls embedded in the ceiling reduce mass and regulate humidity.

This is the real prize: that at almost all scales and regardless of the client, Kundoo’s approach allows for uncommon transfer of knowledge. The Nilgiri Mountains of Tamil Nadu are home to the Keystone Foundation, developed incrementally by Kundoo and her team over the last 20 years. Supporting the organisation’s mission to enhance quality of life for indigenous and tribal communities, Kundoo’s intervention is based on a model of restraint. ‘This is not about making stunning buildings,’ she says. ‘I don’t mind being invisible where necessary.’ Empowering local builders to use their knowledge of rammed earth, and encouraging skill exchanges rather than top-down design solutions, the project has grown into a bricolage of honey and coffee production facilities, a tribal development centre and guest houses, carefully imbricated in the landscape.

My most recent conversation with Kundoo was – like the first – long, frank, passionate and enlightening. The Covid lockdown has, despite its horrors, given us an abundance of time, and she is comfortable making use of it. ‘I’m getting into AI, I’m zooming out with poetry; I’m zooming in with anthropology,’ she enthuses – and she’s not talking about the video conferencing software. ‘This is what is going on in my head.’ She’s still working on futuristic visions, although she doesn’t believe in vast distances between dreams and reality.

Already with several residential schemes under her belt, Kundoo is designing ecological co-housing models on dense urban sites, ‘where the footprint is small, but you have a really good time. I want the human to feel well, individually and collectively.’

Wall House.

The challenge of urban inequality is vividly present in India’s metropolises, and so Kundoo’s attention to it comes as no surprise. A recent project, the Sharana Daycare Centre in Puducherry, negotiates not only the complexity of the city, but how to provide a humane, appealing quality of space, even to the most disadvantaged client. Kundoo is not shy of concrete and render where necessary, and her aim was to produce a building with dignity, which its low-income user group would view with pride. The result is a handsome school for young children with strained home lives, which holds its own against its urbane neighbours. Gently angled classroom walls provide enclosure without suffocation, while cost-saving terracotta ‘jali’ walls allow the building to breathe and retain a connection to context.

Reflecting on her career, Kundoo toys with the idea of writing not a memoir but a self-help book, in which the structured yet sprawling complexity of architecture might offer a way of thinking about life. ‘I do feel like I can offer some way forward. I have imagined scenarios I would like to see happen.’ This instinct reflects the generosity that drives her work: to enable others with knowledge, and to place faith in the positive act of creation. Others may struggle with labels, but for this architect, the category of ‘happy’ would seem to fit best.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

A version of this article first appeared in the April 2021 issue of Wallpaper* (W*264) – available to download here

Hut in Petite Ferme, Kundoo’s low-impact Auroville home built in 1990.

Hut in Petite Ferme features an upper floor of split palm stems.

At Sharana Daycare Centre for disadvantaged children in Puducherry, completed in 2019, terracotta lattice walls create a sense of openness and a connection with the outdoors, while providing shade and ventilation.

Mitra Youth Hostel in Auroville, completed in 2006. The design includes terraces and public space for interaction, and shared bathrooms and kitchens.

INFORMATION

anupamakundoo.com