Bjarke Ingels gives shape to the Virgin Hyperloop

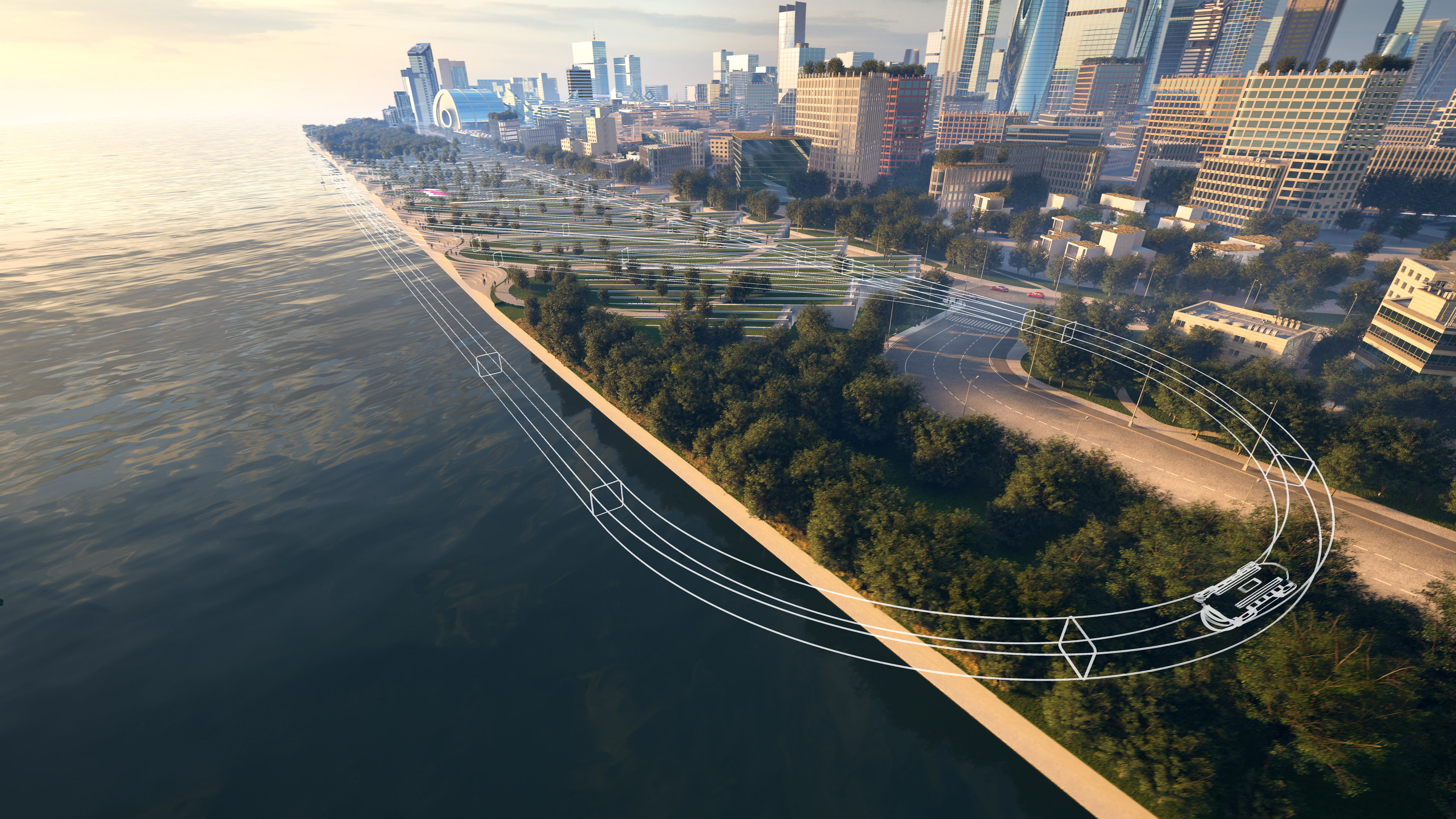

The Virgin Hyperloop – a proposed mode of passenger and freight transportation – is gaining currency, aided by design ideas from BIG. ‘It’s about the destination,' says Bjarke Ingels

The future is all about tubes. At least, that’s what Virgin Hyperloop would have you believe. The company recently released a series of images and a short film to give a flavour of how its far-future transport network will actually function from a passenger’s point of view. Hyperloops, which use frictionless vacuum tubes to enable passenger pods to reach vast speeds, are gaining currency and credibility around the world. The basic concept has been around for centuries, but its modern iteration was popularised by Elon Musk at the turn of the last decade.

Today there are a number of companies competing for funds, partners and routes around the globe. Virgin Hyperloop is perhaps furthest down the line, running human trials on its own test tracks in Nevada, and committing themselves to creating an affordable business model that compares to the cost of driving, not flying. The architect Bjarke Ingels’ firm BIG has a long-running collaboration with Virgin Hyperloop to give form to the massive infrastructure required by this multi-billion-dollar technology.

We spoke to Bjarke Ingels about how his architecture is laying the groundwork for future transportation.

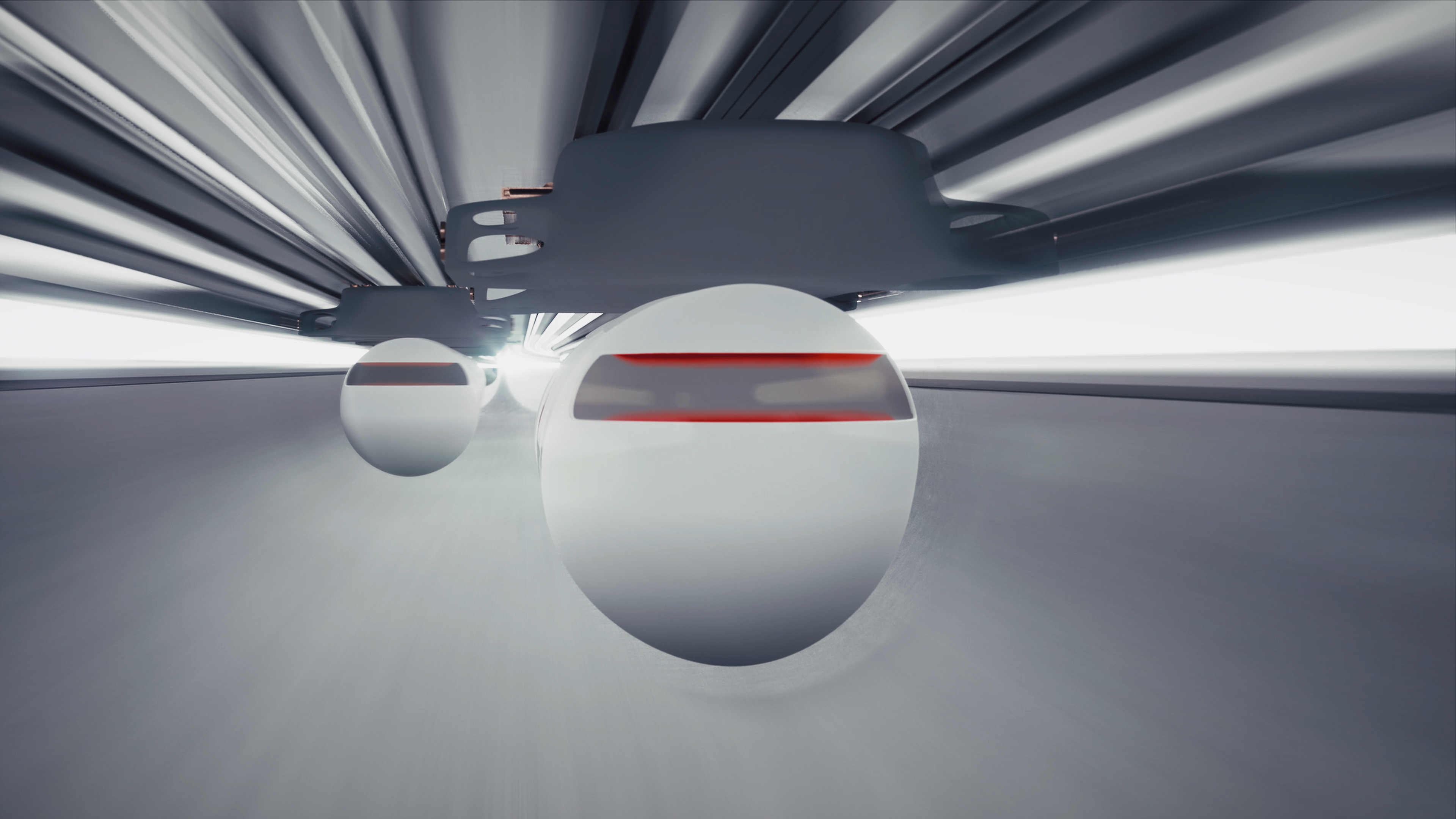

The Virgin Hyperloop will consist of a number of individual 28-seater pods, interior designed by Teague

Wallpaper*: How long have you been working on this project?

Bjarke Ingels: It’s been a long journey. I believe we started working with the Hyperloop guys five years ago. It’s very interesting to be part of a journey where the technology has kept transforming and evolving. In that sense it felt like absolute victory to be able to design the first test vessel, to have an opportunity to try to create something that evokes speed but also feels like it travels inside a void. It’s not aerodynamic in the traditional sense but it still has to be evocative of travelling at an extreme speed in great comfort. I think we've tried to bring some of that vibe to these latest designs. You could say that both airports and train stations have become shopping malls, basically commercializing the waiting time. The economic incentive has gone towards delaying departure and extending the journey rather than shortening it. What we are really trying to do with Hyperloop is to make it as blatant and as immediate as possible. It’s about the destination.

W*: It seems that the laws of physics dictate a huge amount of what you can do in terms of space. How do you accommodate these immense speeds?

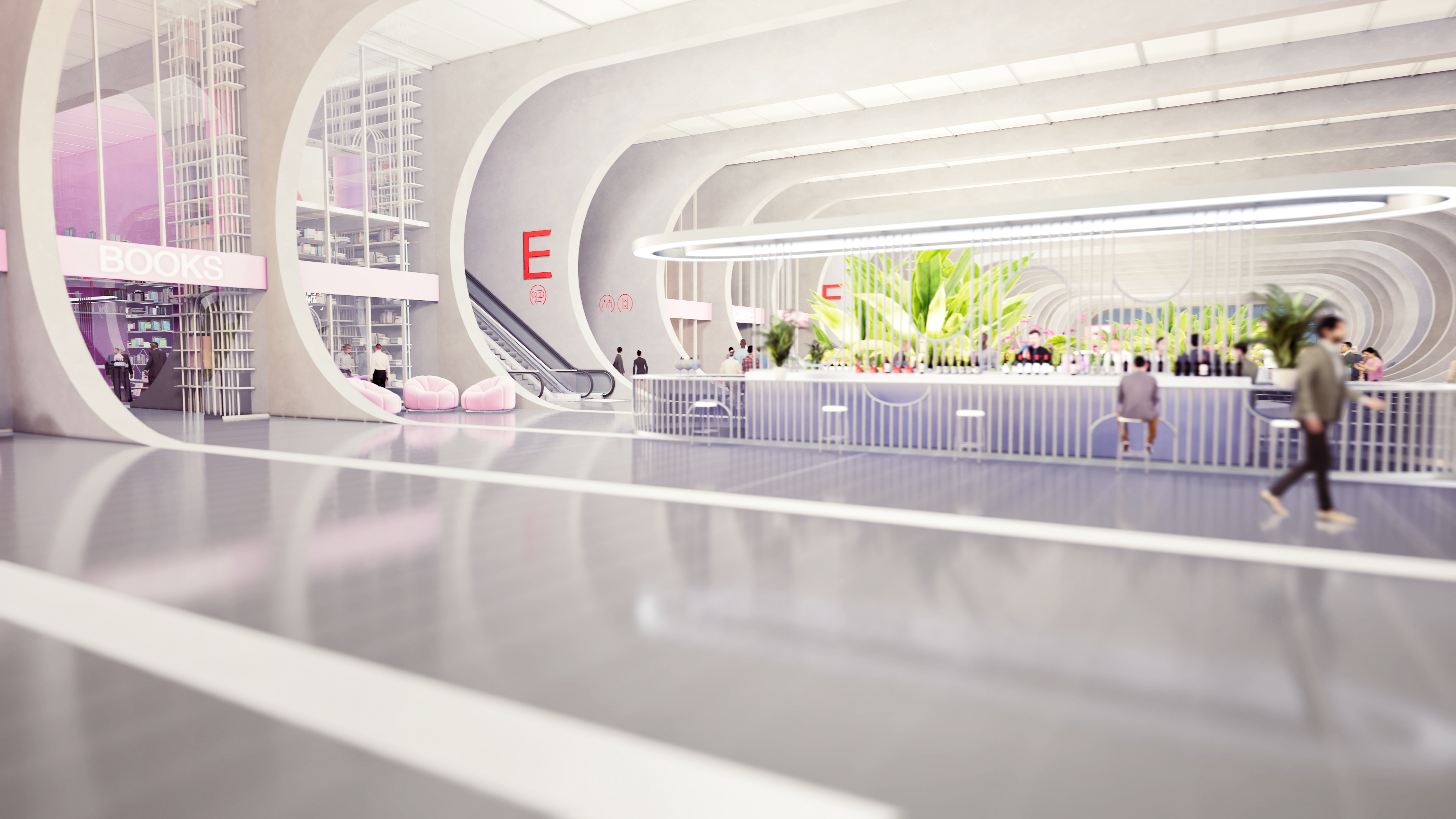

BI: The system is a vacuum tube so you have to pass through an airlock, so the design has to accommodate these elements. You’re essentially going from a normal atmosphere into somewhere that’s equivalent to outer space. The architecture is geared towards making that transition as a seamless as possible. We looked at many different forms of mobility to see if we could combine the best of all worlds. The modern ‘destination dispatch elevator’ became a bit of a reference point. If you go into a modern high-rise you tell the central nervous system of the building which floor you want. It knows where everyone wants to go and groups you with the people going the same way. It reduces travel time and demand load. In a similar way, with Hyperloop you arrive at the Portal it’ll already know where you’re going so you’ll be directed straight to the right pod [shaped by industrial designers Teague]. The building can still be a lovely and beautiful experience, with people waiting for others to arrive, but it has to offer seamless and effortless navigation.

W*: These are conceptual ideas that are designed to encourage cities and countries to make the colossal investment. Where do you personally think we will see the first Hyperloop?

BI: You should speak to the Hyperloop guys about that. I have a feeling that all the studies and conversations are heading something that’s going to be a reality.

W*: BIG usually responds to place and creates buildings that address their immediate environment and the communities that are going to use them. This concept shows how the technology works but suggests it can essentially be plugged into any culture. Is this a weird back-to-front way for an architect to work?

BI: There’s a beautiful poem by Antonio Machado, ‘Caminante no hay Camino’, which means ‘Wayfarer, there is no path’. It goes ‘Wayfarer, there is no way. Make your way by going farther.’ Increasingly, when you are involved in giving form to the future, rather than making an elegant version of something that has been done before, you are literally walking an unpaved path. When you look back, the steps you made are now the beginnings of a path. As architects, we’re not used to doing that. But it is the essence of entrepreneurship. For Hyperloop to make the journey from fantasy to reality, we have to get closer and closer to materialising it in a way that is tangible, credible and desirable. I think that the Hyperloop will be a bit like wireless and cell phones, in the sense that many regions skipped the landline and gone straight to Wi-Fi – perhaps even more will once [Space X’s] Starlink becomes ubiquitous and omnipresent. Similarly, there are places around the world that could skip the stage of installing thousands of miles of conventional tracks and jump straight to Hyperloop. The centre of the world isn’t New York or London, it’s more like Dubai or Mumbai. My bet would be that where you’re really going to see the Hyperloop make a dent in space-time is among the people in Asia and Africa.

W*: Will there be any point in continuing to build airports in the future?

BI: The writer and theorist Paul Virilio had this theory of ‘dromology,’ from dromus, the Greek word for ‘running’. It’s the idea that although increased speed changes things it doesn’t mean that slower speeds cease to exist, but it has less critical impact. Hyperloop is just another avenue for delivering those high speeds, but with all the advantages of connecting dense urban areas to other dense urban areas. It’s like a metro system, but a cosmopolitan one, a Cosmo, I guess, one that interconnects whole cities, not districts. This is where it will make a tremendous difference. With urban mobility, we now know that the answer is not a single silver bullet solution for everything. That’s what we thought the car was – so much so that the US ripped up all the train tracks and the tram lines and the metro systems. It’s increasingly clear that what you need today is a multimodal network. The Hyperloop is incredibly well positioned to be a part of this digitally and physically connected multi-modal transportation network. An instant jump from one city to another, without having to journey out of town to an airport. It could be the missing piece in the intercity connectivity of the future.§

The Virgin Hyperloop portal is designed by Bjarke Ingels and his team at BIG

The 'boarding gates' for the individual pods

Inside the 28-person Virgin Hyperloop pod

INFORMATION

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

Men’s Fashion Week A/W 2026 is almost here. Here’s what to expect

Men’s Fashion Week A/W 2026 is almost here. Here’s what to expectFrom this season’s roster of Pitti Uomo guest designers to Jonathan Anderson’s sophomore men’s collection at Dior – as well as Véronique Nichanian’s Hermès swansong – everything to look out for at Men’s Fashion Week A/W 2026

-

The international design fairs shaping 2026

The international design fairs shaping 2026Passports at the ready as Wallpaper* maps out the year’s best design fairs, from established fixtures to new arrivals.

-

The eight hotly awaited art-venue openings we are most looking forward to in 2026

The eight hotly awaited art-venue openings we are most looking forward to in 2026With major new institutions gearing up to open their doors, it is set to be a big year in the art world. Here is what to look out for

-

Faraday Future’s design director on the cutting-edge FF 91 EV

Faraday Future’s design director on the cutting-edge FF 91 EVFaraday Future design director Page Beermann discusses the joy of clean-sheet design for the FF 91 electric vehicle – ‘simultaneously an intelligent supercomputer and an extreme performance vehicle’

-

‘Pop! Pop! Pop!’: Jeff Koons on the drive behind his new limited-edition BMW 8 Series

‘Pop! Pop! Pop!’: Jeff Koons on the drive behind his new limited-edition BMW 8 SeriesWe speak to Jeff Koons about blending pop, performance and punch in his design for the BMW M850i xDrive Gran Coupé

-

Genesis’ Luc Donckerwolke brings new shapes to luxury mobility

Genesis’ Luc Donckerwolke brings new shapes to luxury mobilityLuc Donckerwolke, Genesis’ chief brand officer and chief creative officer, on its Europe-only G70 Shooting Brake, the new Genesis EV60 electric vehicle, and the shape of cars to come

-

Through the lens of photographer Milo Lethorn

Through the lens of photographer Milo LethornHere, Milo Lethorn discusses the eroding perceptions of photographic ‘truth’, the marketisation of higher education, and pushing the boundaries of genre

-

New era for BMW electric cars, says design chief Domagoj Dukec

New era for BMW electric cars, says design chief Domagoj Dukec‘BMW i models are becoming the most relevant part of the brand,’ says the company’s head of design Domagoj Dukec, as he talks about a trio of new BMW electric cars, the iX3, i4 and iX, and what they mean for the future of the brand

-

Citroën's Pierre Leclercq on the brand’s bold future

Citroën's Pierre Leclercq on the brand’s bold futureThe Citroën head of design discusses the architecture of automation, utility, versatility, and more

-

Explore the world of bespoke automotive design with Italian coachbuilder Ares

Explore the world of bespoke automotive design with Italian coachbuilder Ares‘Uniqueness is more and more important,’ says CEO Danny Bahar as the company unveils its new Ares Design Coupé, a limited edition of eight and a radical reimagining of a classic

-

The zero emission delivery vehicle elevating ecommerce

The zero emission delivery vehicle elevating ecommerceCanoo’s new MPDV (Multi-Purpose Delivery Vehicle) makes zero emission business transportation inexpensive and easy