Design & Interiors

Travel with us to design weeks and experience refined interior design from across the globe. Get the first look at all-new modern furniture, and contemporary craft every day

Explore Design & Interiors

-

2026 horoscope: design for every star sign

For the Wallpaper* 2026 horoscope, we asked Italian astrologist Lumpa what the stars have in store for the year ahead, and what design objects each sign will need to face the new year

By Lumpa Published

-

Glass designer Silje Lindrup finds inspiration in the material's unpredictability

Wallpaper* Future Icons: Danish glassmaker Silje Lindrup lets the material be in charge, creating a body of work that exists between utility and experimentation

By Ali Morris Published

-

Zbeul Studio's 'future relics' merge traditional craft with unexpected materials

Wallpaper* Future Icons: Paris-based studio Zbeul merges archaeology, craft, and design, taking the design process to innovative places

By Shawn Adams Published

-

Design studio Palma is a tale of twos, where art and architecture meet

Wallpaper* Future Icons: in São Paulo, artist Cleo Döbberthin and architect Lorenzo Lo Schiavo blur the lines between making and meaning. Through Palma, they explore a dialogue shaped by material, memory and touch.

By Hiba Alobaydi Published

-

Grace Atkinson's Ukraine-made textiles balance material and emotion

Wallpaper* Future Icons: New Zealand-born Grace Atkinson creates sensual domestic textile objects using 14th century techniques

By Ali Morris Published

-

7 colours that will define 2026, from rich gold to glacier blue

These moody hues, versatile neutrals and vivid shades will shape the new year, according to trend forecasters

By Kelly Allen Published

-

An inox-fanatic's love letter to stainless steel

Ultimate stainless steel fan Levi Di Marco has been documenting inox designs on his social media platform @tutto_inox: we asked him to tell us about his not-so-mild obsession and share some of his favourite examples of inox design

By Levi Di Marco Published

-

The Testament of Ann Lee brings the Shaker aesthetic to the big screen

Directed by Mona Fastvold and featuring Amanda Seyfried, The Testament of Ann Lee is a visual deep dive into Shaker culture

By Emma O'Kelly Published

-

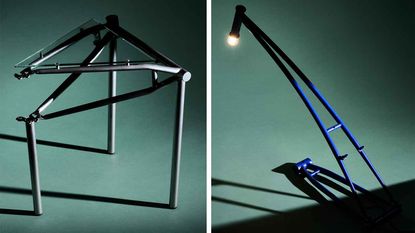

Eddie Olin's furniture that merges heavy metal with a side of playfulness

Wallpaper* Future Icons: London-based designer and fabricator Eddie Olin's work celebrates the aesthetic value of engineering processes

By Ali Morris Published

-

The work of Salù Iwadi Studio reclaims African perspectives with a global outlook

Wallpaper* Future Icons: based between Lagos and Dakar, Toluwalase Rufai and Sandia Nassila of Salù Iwadi Studio are inspired by the improvisational nature of African contemporary design

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

Korean designer Yoonjeong Lee tells ordinary stories in extraordinary ways

Wallpaper* Future Icons: Yoonjeong Lee's work is based on a fascination for utilitarian objects, from pencils to nails, recreated with innovative casting methods

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

Volvo’s quest for safety has resulted in this new, ultra-legible in-car typeface, Volvo Centum

Dalton Maag designs a new sans serif typeface for the Swedish carmaker, Volvo Centum, building on the brand’s strong safety ethos

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

We asked five creative leaders to tell us their design predictions for the year ahead

What will be the trends shaping the design world in 2026? Six creative leaders share their predictions for next year, alongside some wise advice: be present, connect, embrace AI

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

Patricia Urquiola reveals an imaginative inner world in ‘Meta-Morphosa’

From hybrid creatures and marine motifs to experimental materials and textiles, Meta-Morphosa presents a concentrated view of Patricia Urquiola’s recent work

By Ali Morris Published

-

This LA-based furniture designer finds a rhythm in music and making

Wallpaper* Future Icons: LA-based Ah Um Design Studio's expressive furniture features zig-zagging wooden frames, mohair and boucle upholstery, and a distinctive use of tiles

By Ali Morris Published

-

Pull up a bespoke pew at Milan’s new luxury perfumery Satinine, an homage to the city’s entryways

Designer Mara Bragagnolo fuses art deco details to bring storied Milanese fragrance brand Satinine into the 21st century

By Ifeoluwa Adedeji Published

-

Supersedia’s chairs combine sculptural forms with emotional expressions

Italian design studio Supersedia, founded by Markus Töll, creates furniture where ‘every detail is shaped individually'

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

How Stephen Burks Man Made is bringing the story of a centuries-old African textile to an entirely new audience

After researching the time-honoured craft of Kuba cloth, designers Stephen Burks and Malika Leiper have teamed up with Italian company Alpi on a dynamic new product

By Anna Fixsen Published

-

Togo's Palais de Lomé stages a sweeping new survey of West African design

'Design in West Africa' in Lomé, Togo (on view until 15 March 2026), brings together contemporary designers and artisans whose work bridges tradition and experimentation

By Laura May Todd Published

-

Australian studio Cordon Salon takes an anthropological approach to design

Wallpaper* Future Icons: hailing from Australia, Cordon Salon is a studio that doesn't fit in a tight definition, working across genres, techniques and materials while exploring the possible futures of craft

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

This designer’s Shoreditch apartment is ‘part grotto, part cabinet of curiosities’

The apartment serves as Hubert Zandberg’s ‘home away from home’, as well as a creative laboratory for his design practice. The result is a layered, eclectic interior infused with his personality

By Anna Solomon Published

-

How Taipei designers operate between cutting-edge technology and their country's cultural foundations

In the final instalment of our three-part Design Cities series, we explore Taipei, Taiwan, as a model of translating contemporary urban aesthetic and craft traditions into design thinking

By Laura May Todd Published

-

How Charles and Ray Eames combined problem solving with humour and playfulness to create some of the most enduring furniture designs of modern times

Everything you need to know about Charles and Ray Eames, the American design giants who revolutionised the concept of design for everyday life with humour and integrity

By Francesca Perry Published

-

Veronica Ditting’s collection of tiny tomes is a big draw at London's Tenderbooks

At London bookshop Tenderbooks, 'Small Print' is an exhibition by creative director Veronica Ditting that explores and celebrates the appeal of books that fit in the palm of your hand

By Ali Morris Published

-

How Beirut's emerging designers tell a story of resilience in creativity

The second in our Design Cities series, Beirut is a model of resourcefulness and adaptability: we look at how the layered history of the city is reflected in its designers' output

By Laura May Todd Published

-

How Abidjan's Young Designers Workshop is helping shape a new generation of Côte d'Ivoire creatives

In the first in our Design Cities series, we look at how Abidjan's next generation of creatives is being nurtured by an enlightened local designer

By Laura May Todd Published

-

Colour and texture elevate an interior designer’s London home

To beautify her home without renovations, Charu Gandhi focused on key spaces and worked with inherited details

By Anna Solomon Published