Odile Mir: exploring the creative life of a self-taught polymath

Nonagenarian French artist Odile Mir is back for an encore, thanks to her granddaughter’s role in reissuing her modernist designs

Sophie Tajan - Photography

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Tucked into a courtyard behind an apartment building in Toulouse, a small house with a yellow floor overflows with photos, religious icons, art books, drawings and sculptures. The last include a larger-than-life statue of a slim nude woman with an exaggerated vulva, her head replaced by a visibly male flying dog. On a recent autumn day, the house’s 96-year-old owner, Odile Mir, greeted visitors wearing a loose shirt over jeans and dangly silver earrings. A cane was the only concession she gave to her age.

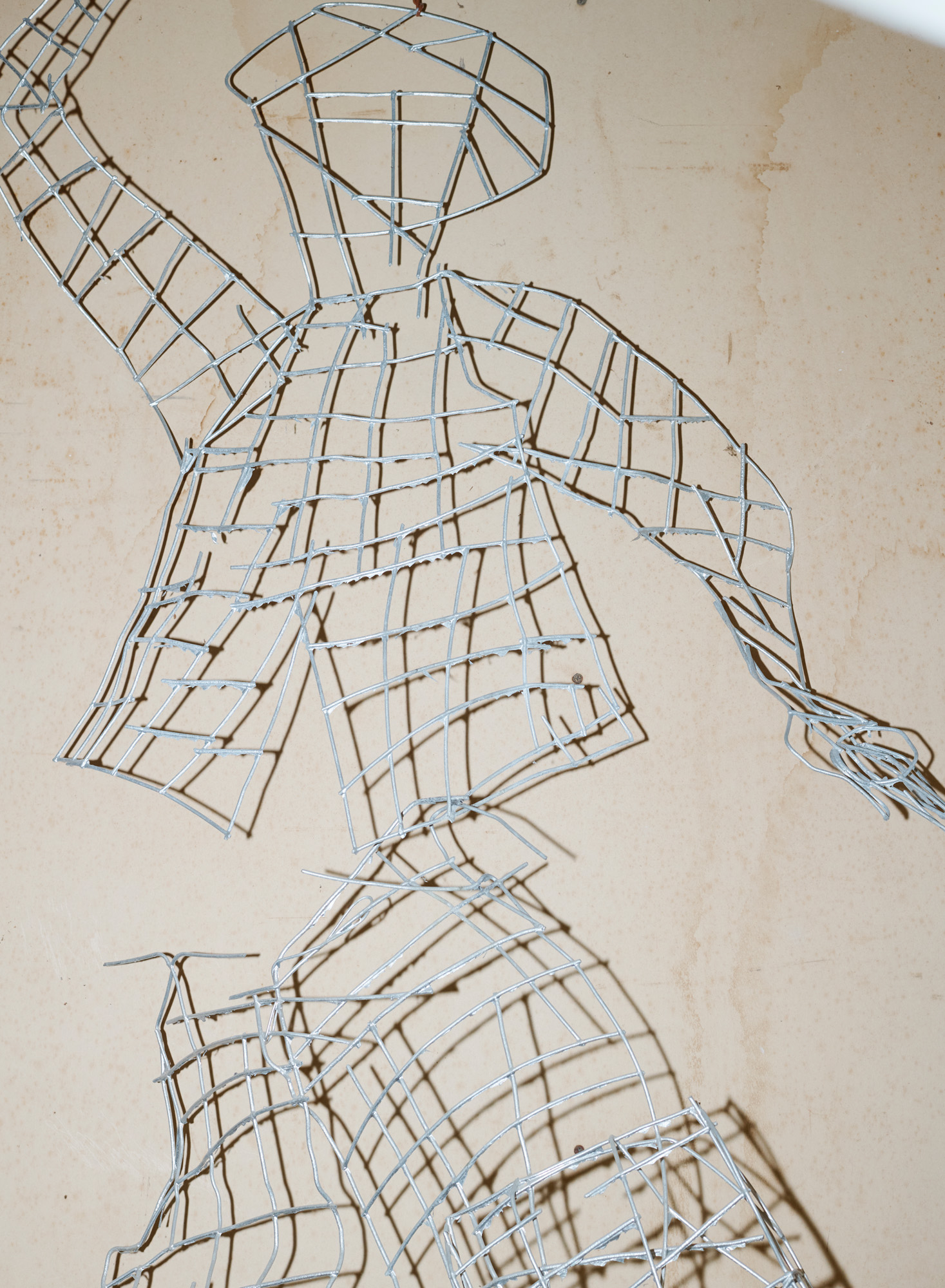

Mir is a self-taught artist who had a seven-year parenthesis as a self-taught furniture designer. She is best known for her sculptures, which she makes using wire grids covered with plaster, then painted leather or paper. Inspired by mythology, her artwork is both alluring and disturbing – headless women, disfigured animals, bodies wrapped like mummies. She says she doesn’t consciously choose her themes: ‘At night, when I’m lying half asleep, I feel shapes enter my body. They tell me what to do the next day.’

A wire sculpture by Mir

Her work is powerful and original, though she never gained public renown. ‘I worked a lot, but nobody knew who I was,’ she says. ‘No gallery was interested, and I didn’t have the right contacts. Plus, my work was too big – no madame wanted that [she indicates the headless sculpture] in her salon.’ It probably didn’t help that Mir is a woman and has spent most of her life in the countryside.

Nonetheless, her sculptures have been acquired by a number of French museums, including the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris. Last summer, Mir’s artwork was the subject of a three-month retrospective at the Musée du Vieux Toulouse. Pierre Nouilhan, who organised the exhibition, notes, ‘She is exceptionally creative. Her work is strong, violent, sexual. Some visitors found it too violent. But those who are interested in art were surprised by its force and coherence.’

Odile Mir: a self-taught polymath

Odile Mir sitting in a vintage ‘Filo’ chair

Mir was born in 1926 in Toulouse, to a family of bourgeois landowners whose fortunes declined in the 20th century. Her paternal grandfather was killed in battle on 22 August 1914, the bloodiest day in French military history, and her father, who also fought in the First World War, suffered afterwards from depression. Her maternal grandmother lived with the family, knitting and embroidering, and the first thing Mir did with her hands was darn socks. ‘I loved it,’ she recalls. ‘I did it for fun.’

After the Second World War, Mir moved with her family to Casablanca, where she briefly attended the Beaux-Arts academy and worked with a live model for the first time. The result, a small plaster sculpture of a woman’s torso, sits on a windowsill. 'I can’t say anyone taught me,’ she says. ‘They gave me the means to work, and I haven’t stopped working since.’

She met her husband, a member of the Resistance, while working at the French consulate. In 1955, after the birth of their daughter, they moved back to a farm in rural France. Mir continued to sculpt and draw, showing her work in small exhibitions. A blacksmith in the village taught her to weld.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Design beginnings

A vintage ‘Filo’ chair in chrome and cowhide

In 1966, she made herself a couple of lamps with a welded spine and a spherical head, dubbed ‘Le Phare’ (The Lighthouse). ‘I must have needed lamps because we had no money,’ she says. Mir is not sure how one ended up in a gallery exhibition on Place Vendôme in Paris, alongside work by sculptors César and Philolaos. A couple of well-known agents specialising in product promotion saw it and put Mir in touch with the Delmas lighting factory in Montauban, north of Toulouse.

Delmas was well-respected, but its style was traditional – Mir notes that the factory ‘made nothing beautiful’. The company gave her a workspace, a technician, and a few days to come up with something. ‘I made several lamps, left after 15 days, and had no news. Then someone called me: “The lighting trade fair is in two months, come back”.’

Working as a freelancer, Mir was able to do what she wanted, and she happily stayed late into the night, pursuing her personal projects after everyone else had gone home. Because the factory was far from home, she rented a nearby studio. She created about 40 design pieces, mostly lamps, chairs and tables. Her approach to creating furniture was similar to her art – a tubular chrome frame, draped or upholstered with leather or fabric – and minimalist, in the tradition of Pierre Paulin or Charlotte Perriand.

A photograph of Odile Mir’s ‘David’ armchair, and ‘Filo’ chairs and footstool, from the Delmas factory archives

One day, she noticed the factory had placed some of her prototypes in the reception area. A visiting buyer from Printemps department store asked about them, and Mir has always remembered her boss’s disparaging response: ‘It’s the patternmaker just fooling around.’ Knowing better, Printemps took a few of Mir’s pieces for the display windows of its Parisian flagship, including the ‘David’ chair, which features a crisscrossing chrome frame and a leather seat suspended like a hammock from one high point.

Printemps also owned Prisunic, a national chain of reasonably priced stores, which produced a furniture mail-order catalogue with contemporary designs by the likes of Terence Conran – its slogan was ‘beautiful for the price of ugly’. Mir’s industrial, affordable, modern designs were a perfect fit, and the cover of the autumn-winter 1974-75 catalogue featured a cat sitting on her ‘Fil’ modular armchair.

Return to art

Mir’s house is filled with prototypes of her sculptures

But by then, Mir had given up design. In 1973, fire destroyed part of the Delmas factory, putting an end to its budding furniture department. Losing access to her tools and technician, she returned to sculpture. A few years later, an acquaintance offered her a courtyard studio in Paris. It had neither water nor electricity, but she fixed it up and moved in, continuing her art while making a living doing odd jobs. At age 60, she returned to Toulouse and bought the house she lives in today. It was in rough shape, so she painted the floor, installed skylights and a mezzanine, and built a trapdoor to her basement workshop, along with pulleys to help her open the shades and trapdoor.

As time goes on, and Mir grows older, she rarely descends the steep staircase to her workshop, and the trembling of her hands makes it difficult to draw or thread a needle. But her mind and imagination are as sharp as ever, and she still has the thirst to create. She says, ‘If I can’t work with my hands, I have no life.’ Even as she talks, she reflexively picks up a paper napkin and pleats it.

Preserving her work for the future

A photograph of the artist with La Nef Solaire, her 17m-high sundial built in 1993 alongside a highway linking Orange and Nîmes in France

About eight years ago, an antiques dealer named Antoine Broccardo bought Mir’s original ‘Le Phare’ lamp from a colleague. Learning she was still alive, he went to meet her in Toulouse, where he saw a half-finished chair from 1967 in the basement, and encouraged her to complete it. She covered it in paper, gilding parts. ‘It was a magic chair, so beautiful,’ says Broccardo. Like the lamp, it obviously came from the hand of a sculptor. He showed it at the PAD design and art fair in Paris, and claims, ‘I could have sold it five times over.’

Perhaps that is why, in 2018, Mir asked her granddaughter, Léonie Alma Mason, an interior designer and the founder of LAM Studio, to help her realise a limited re-edition of the ‘David’ chair. ‘I knew about the chair, had seen photos of prototypes, but we never really talked about it,’ says Alma Mason. ‘I started to get interested in the story of her design.’ Going through her grandmother’s archives, she realised there were dozens of different models. ‘I found them incredibly contemporary, not old-fashioned at all. Some of the chairs look as though they could have been designed in the 2020s.’

Alma Mason created a company, LOMM Editions (a combination of their initials), to reissue Mir’s pieces from the 1960s and 1970s. They showed the first ones in 2021 at the Joyce Gallery in Paris, and produced a catalogue raisonné of Mir’s designs.

The collaboration did not end there. In the 1980s, Mir came up with a model for an enormous sundial with four concrete sails. A gnomonist perfected the technology and, in 1993, it was built alongside a highway linking Orange and Nîmes, becoming one of the world’s largest sundials at 17m in height.

Last autumn, Mir and her granddaughter stood at her dining table, going through abstract photos of the sundial, upon which Mir had etched a few words – a new art project for a gallery in Paris. The exhibition features the photographic work of Thomas Paquet, including his collaboration with Mir inspired by her sundial, as well as six ‘Filo’ chairs by LOMM Editions. A new take on the original models first produced by Prisunic in the 1970s, the unique chairs will have an original photo by Paquet printed on the leather.

Mir recalls the hoops she had to jump through to get the sundial built, and the many years it took. But she has never been one to give up hope, nor her sense of wonder. ‘When I was a child, I had cholera,’ she says. ‘My doctor said I must have been solid to still be here today. A woodpecker drilled holes in my bedroom shutters, where a ray of sun entered and climbed the wall. These childhood memories have carried me ever since.’

‘Rien n’échappe à la lumière’ runs until 15 April 2023

Galerie Bigaignon

18 Rue du Bourg Tibourg

Paris 4e

bigaignon.com

lommeditions.com

A version of this story appears in the April 2023 issue of Wallpaper*, available now in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Amy Serafin, Wallpaper’s Paris editor, has 20 years of experience as a journalist and editor in print, online, television, and radio. She is editor in chief of Impact Journalism Day, and Solutions & Co, and former editor in chief of Where Paris. She has covered culture and the arts for The New York Times and National Public Radio, business and technology for Fortune and SmartPlanet, art, architecture and design for Wallpaper*, food and fashion for the Associated Press, and has also written about humanitarian issues for international organisations.