A tribute to William Klein (1928-2022), legendary photographer of urban life

William Klein, the American-French artist responsible for transforming the worlds of fashion photography, street photography and cinema verité, has died in Paris aged 96

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

William Klein, one of the pioneering fathers of street photography, once an unhappy child of 1950s Manhattan who became a much-loved artist, has died at the age of 96 in Paris. ‘I came from the outside,’ Klein once said.

He was born in 1928 in a small apartment on Broadway, near 110th Street, in Manhattan, New York. He was the grandson of Jewish-Hungarian immigrants and grew up in a working-class Jewish family in an area where anti-Semitism was common. He credited, as a boy, spending time alone creating art as a way to escape the bullies on the street or his distant parents at home. He would frequently take solo trips to New York’s Museum of Modern Art, before studying, as a quiet but precocious teenager, at the City College of New York.

Throughout his life, Klein gained more recognition in France and Europe than in the country of his birth. He left America at the age of 18 to join the American military in its effort to stabilise Europe in the immediate aftermath of World War Two, and was initially stationed in numerous destinations across Germany before, at 20, being posted to Paris, France.

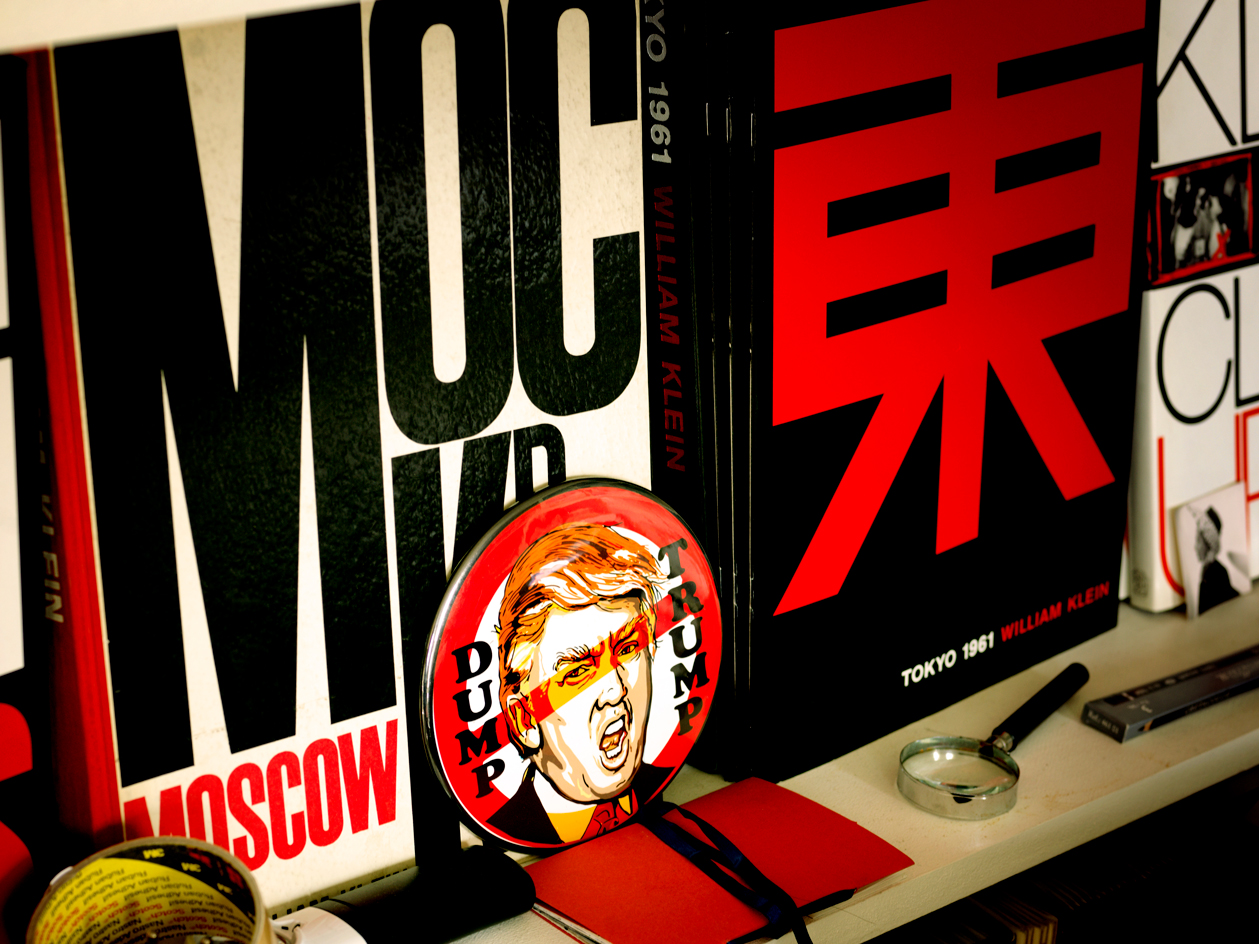

Objects lining the shelves of William Klein's Paris studio.

Growing up, Klein had rarely left the confines of New York – even Brooklyn or the Bronx were like a ‘foreign country,’ he said. He quickly fell in love Paris. ‘I realised there are other ways of making a city,’ he said in an interview. After he was discharged, Klein decided to remain in Paris, and using his military status to subsidise the fees, he enrolled at Paris’ famous Sorbonne, where he pursued abstract painting in the style of Piet Mondrian and the Bauhaus movement.

‘The love affair of the century’

A few months after arriving in the city, Klein was cycling to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts when he saw a girl walking along the pavement. ‘I’d never seen anyone so beautiful,’ he said. He stopped to ask her directions (despite not needing any) and then asked what she was doing that evening. Soon after, Klein married Jeanne Florin. The pair remained together until her death in 2005, living in a book-filled apartment overlooking the Jardin du Luxembourg. He called their relationship ‘the love affair of the century’.

At the Sorbonne, Klein came under the influence of Fernand Léger, the unconventional son of a cattle farmer, and a multimedia artist comfortable with paint, sculpture, film and photography. Léger, who is now considered an early forerunner of Pop Art, pushed Klein to push beyond an easel. Klein started to experiment with a saturated form of monochrome photography and processing techniques in a dark room.

Spanish Steps, Simone d'Aillencourt, Nina Devos, Capuci, 1958 © William Klein (Courtesy HackelBury Fine Art, London)

‘I was a primitive, and the photographs I was taking for myself were at the level of zero in terms of the evolution of photography’, Klein said of these early experiments. ‘But once I had the opportunity to take the negatives and print them my way, I realised that I could use what I had learned – about graphic art, painting, and charcoal drawings, and so on – in my printing.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Soon after, Klein got his big break; some of his early photographs, of a building he had shot geometrically whilst on a trip to Italy, made their way into the hands of Alexander Liberman, American Vogue’s legendary art director. Liberman was intrigued and invited Klein to work for the magazine.

In 1954, Klein started to split his time between Paris and New York, and throughout the late 1950s and 1960s, became a renowned fashion photographer for Vogue, one happy to experiment with new exposure and processing techniques, grain, contrast, blur, unusual shading, odd angles.

‘The rules of photography didn't interest me,’ he said. ‘There were things you could do with a camera that you couldn't do with any other medium. I thought it would be good to show what's possible, to say: “This is as valid of a way of using the camera as conventional approaches.”’

RELATED STORY

Hat and Five Roses, Barbara Mullen, Paris, 1956 © William Klein (Courtesy HackelBury Fine Art, London)

Finding freedom in street life: ‘I just photographed the shit out of New York’

After spending the day shooting for Vogue, Klein would walk the streets of New York, photographing the people of the streets at the same time as fellow luminaries like Diane Arbus, Saul Leiter and Bruce Davidson.

‘I thought photography was way behind the other arts, and I thought I could take what I’d learned from painting and could use that in photography. So I went out on the street and I just photographed the shit out of New York,’ he said. ‘I was free to do what I wanted. I didn’t know I was doing anything revolutionary. I was fascinated with faces, and I would go into crowds and really take photographs at point blank. No one would look at me.’

He decided to work on a book of street portraits, and subsequently turned the bathroom of the low-grade hotel in which he was living into a darkroom. ‘I washed the prints in the bathtub, and now these prints are considered “vintage prints”.’

Klein won the Prix Nadar, one of France’s top photography prizes, in 1957 for the resulting monograph, which Klein titled Life is Good & Good for You in New York. But the experience also helped to turn Klein further away from the city of his birth. Klein had initially offered the work, which had a distinct fashion ethos, to his employers at Vogue, but the magazine deemed the images too vulgar, dark and ambivalent. Klein returned to Paris, and the work was soon published by a Parisian imprint. The work remained untouched by any American publisher until 1995.

On William Klein’s shelves, Moscow and Tokyo, from his series of city books

But, by the time he had published his first monograph, he had started to harbour further creative ambitions. He made a series of other books: Trance Witness Revels (1956), Rome (1958–59), Tokyo (1964), and Moscow (1964). He became friends with the Parisian filmmakers Chris Marker and Alain Resnais, and, in 1958, released Broadway by Light, a moody and dark evocation of the streets near his family home. The film was admired by Orson Welles, and Klein gained a spot as an assistant director for Louis Malle’s Zazie dans le Métro. Not a man to feel comfortable ceding creative control, Klein walked out on the project when shooting began.

Klein would continue to work for Vogue until 1966, but his distaste for the fashion editors started to grate. The year he left, he released Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?, a razor-sharp, biting satire of the fashion industry, with model Dorothy McGowan in the lead role. Then, in 1974, he released cinema verité documentary Muhammad Ali: The Greatest, perhaps the greatest ever film about the sport of boxing.

The film is split into separate fights. The first chapter, shot in black and white, follows the then Cassius Clay in his first match against Sonny Liston in 1964. Klein then captures Klein’s switch to Muhammad Ali after joining the Nation of Islam, before beating Liston again in 1965. The second half of the movie, shot in colour, takes place ten years later in Kinshasa – the so-called ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ against George Foreman that took place after Ali had been stripped of his title for refusing to serve in the Vietnam War.

Klein will be remembered as one of the greatest filmic artists of his age, a man who progressed, single-handedly, the sub-genres of fashion photography, street photography and cinema verité. ‘Half of everything I’ve done is chance,’ he once said. Maybe so. But Klein’s life is a testament to how one grabs the opportunities that come your way, without ever losing sight of who you are.

Dorothy + white light stripes, Paris, 1962 © William Klein (Courtesy HackelBury Fine Art, London)

INFORMATION

Tom Seymour is Museums and Heritage Editor of The Art Newspaper

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.