Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the church

The American artist considers depression and the suppressed queerness of his childhood in a series of intensely personal paintings, on show at Half Gallery, New York

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Leonard Baby grew up in a fundamentalist mega-church in Colorado Springs. Largely removed from outside communities, congregations spoke in tongues and leaders preached extreme conservative values that, among other things, stated that being gay was a sin. Growing up with four sisters whom he describes as ‘angels’ who helped him survive the traumas of their family home, Baby was deterred from playing with girly toys as a child and was later subjected to conversion therapy in middle school. He escaped to New York when he was 17. ‘It felt like I could finally breathe,’ says the artist, who nowadays lives and works in Bushwick, Brooklyn. ‘Here, if you wanted to, you could walk onto the subway fully nude and no one would bat an eyelid. It was just immediate freedom.’

Leonard Baby, Far From the Twisted Reach of Crazy Sorrow, 2024 - 25

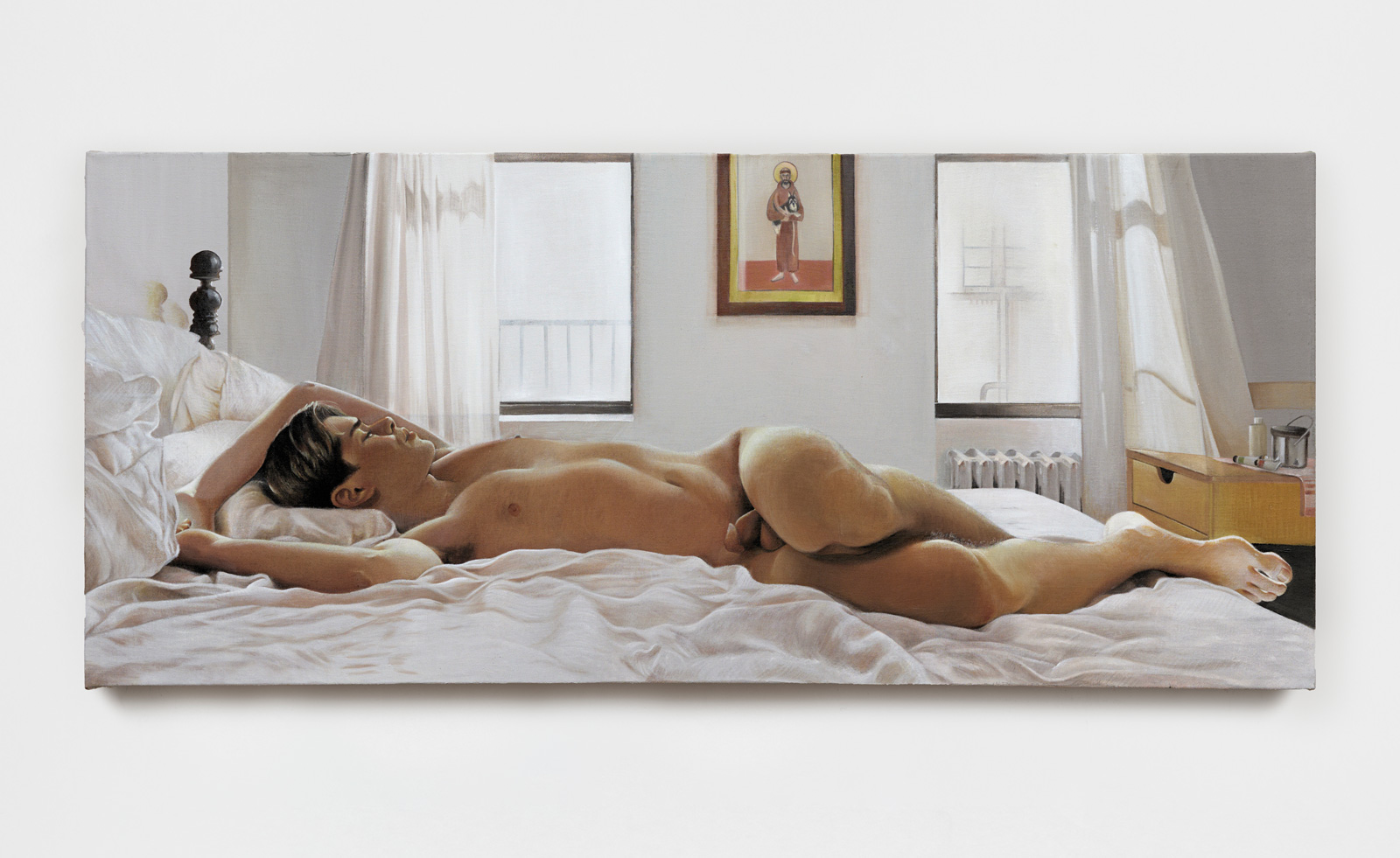

Over a decade on from leaving the church, Baby is delving into his upbringing for the first time in a new exhibition at Half Gallery in Manhattan. Navigating the suppression of queerness and femininity in evangelical households, ‘The Babys’ features domestic portraits of his sisters, a sun-dappled nude study of his boyfriend, and his very first self-portrait. Touching upon the difficult subject of suicide, the classically inflected painting takes after the story of Lucretia – a noblewoman in ancient Rome who committed suicide after being raped by the king’s son – while an Edgar Degas-inspired sculpture work sees a 1930 ballet costume suspended from the ceiling by a rope.

The show is both a meditation on what it feels like to live in a space where you can’t be yourself, and a tender celebration of the bonds shared between siblings. ‘My sisters are my best friends,’ he says. ‘More than dwelling on the tougher emotions, I do hope the mood is celebratory. I feel so lucky to have them in my life.’

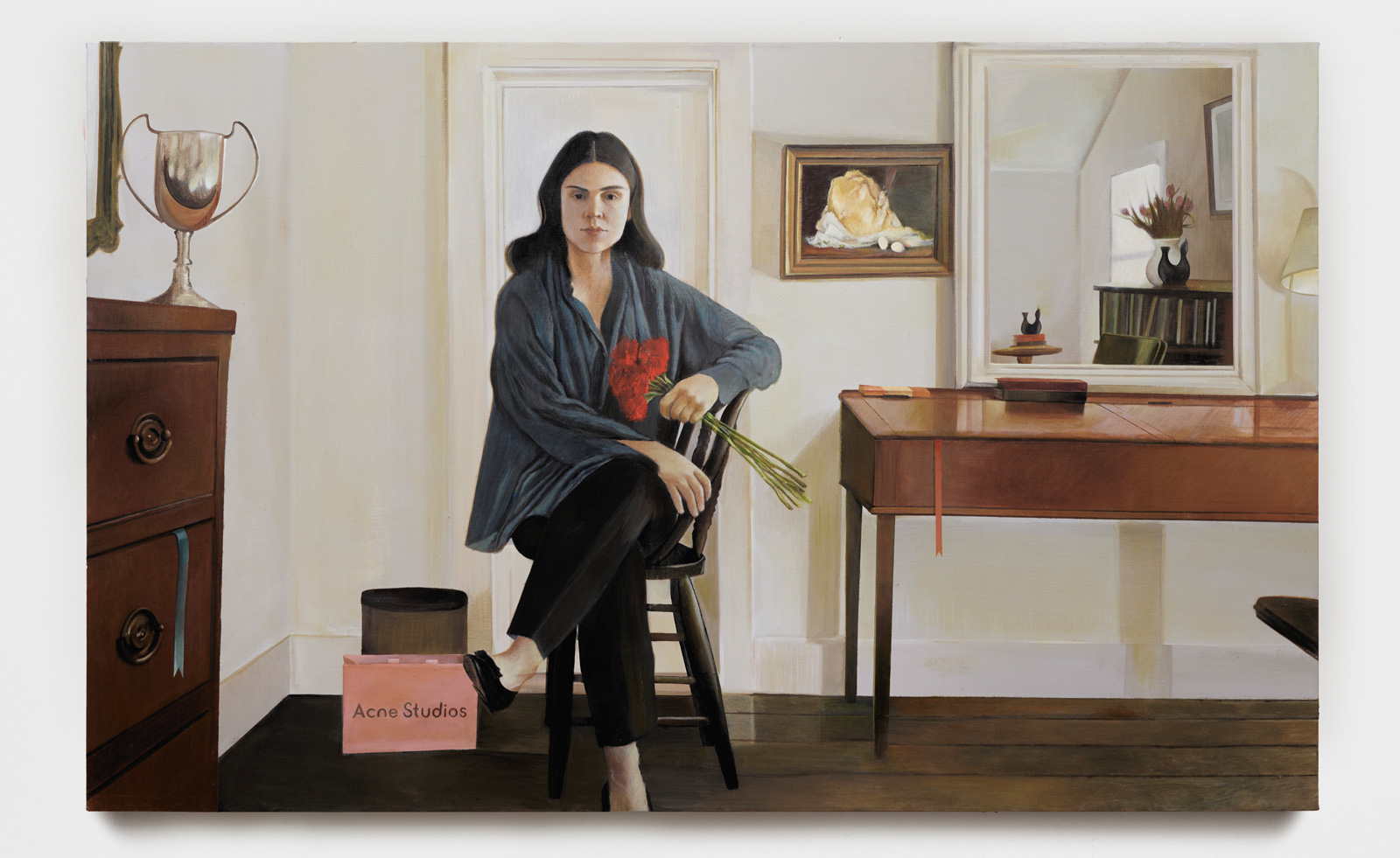

Leonard Baby, Four Sisters. 2024 - 25

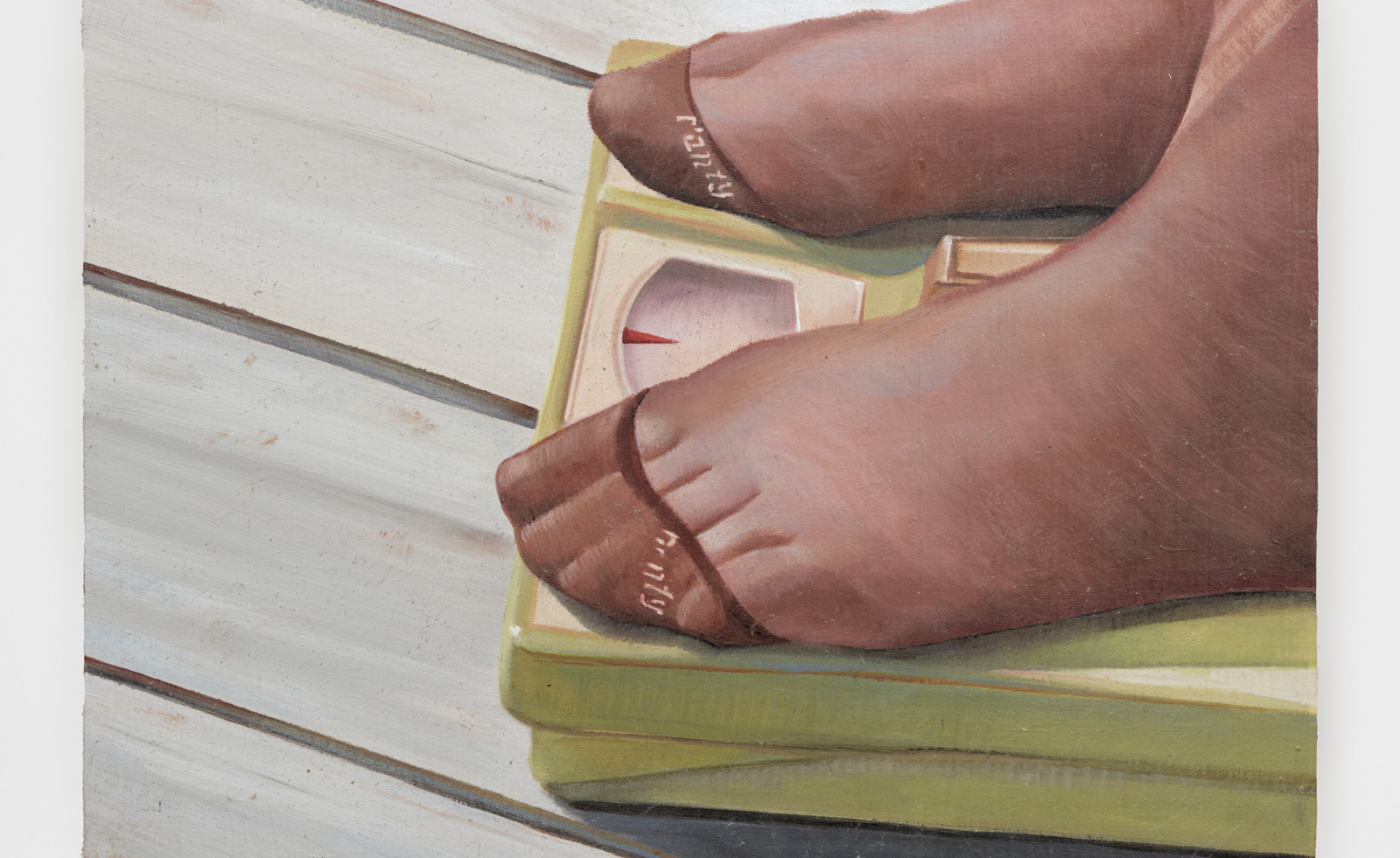

Beyond its personal subject matter, the exhibition sees Baby explore new shores in his practice. Up until now, the self-taught painter has plucked compositions from auteurs like Jean-Luc Godard and Robert Bresson, transforming black and white frames into vividly rendered acrylic scenes that simmer with the pregnant suspense of a moment. Rarely including faces, his paintings focus on familiar moments of everyday American life – breakfast in bed, the shuffling of books on desks, school kids gathered on bleachers – using them to reflect upon subjects of identity and otherness.

‘I don’t discriminate. I’ve painted from The Kardashians. Some of my favourite pieces are stills from The Princess Diaries’

Leonard Baby

Baby learnt the language of cinema early on, secretly watching films at night and later working at a movie theatre upon arriving in New York. Alongside European masters and directors like Lars von Trier and Sofia Coppola, he’s also gleefully stolen snapshots of beauty from lowbrow pop culture. ‘I don’t discriminate,’ he says with a gentle laugh. ‘I’ve painted from The Kardashians. Some of my favourite pieces are stills from The Princess Diaries. It's a really beautiful movie.’

Baby’s new body of work has much of the cinematic drama of his previous paintings, but for the first time expressed in portraits of people close to him. In preparation, he gathered his sisters at their mother’s home in Tennessee (he has a good relationship with his mum but is estranged from his dad), staging compositions inspired by religious masterpieces and the controversial works of Balthus. ‘I first got the idea when I was in London,’ he says. ‘I saw Bryan Organ's acrylic portrait of Princess Diana at the National Portrait Gallery and it just blew me away. It made me want to do a show of portraits. I dressed all of my sisters, did the props, for lack of a better term, and photographed them. It was just a ton of fun to do. It feels like I directed a film for this show.’

Leonard Baby,Girlfriend, 2024

Mixing scenes of domestic suffocation with moments of personal reprieve, Baby’s paintings are scattered with referential Easter eggs specific to each of his sisters. In the portrait of his twin, Sophie, a magazine clipping of the late music producer SOPHIE sits upon the desk – ‘listening to her music reminds me of my twin’ – while an image of the Twin Towers is hidden on the wall. ‘We were just living through the aftermath of that and it was very strange,’ Baby says. ‘It also makes sense because we're twins.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Elsewhere, in his younger sister’s portrait, Lana Del Rey appears behind her shoulder like a Madonna figure, while in the especially beautiful painting of his boyfriend stretched out nude in bed, a painting of the benevolent Saint Francis hangs beside the window. ‘He grew up in a similar background to me, but Mormon in Utah,’ the artist says. ‘I found a lot of the process of making these uncomfortable; I still find them uncomfortable, but that one was the easiest to paint. It was fun and kept me entertained.’

Leonard Baby, Grey Gardens Painting, 2024

Knowing he wanted to place himself in the story somewhere, Baby’s self-portrait is perhaps the most confronting of the series. ‘I went to the ballet with my gallerist and during the intermission he leaned over to me and said, “I was just thinking, there's that song by Björk called Venus as a Boy, don’t you think a painting called Lucretia as a Boy would be interesting?” It’s been explored a lot through art history and the story really resonated with me. It's a dramatic suicidal composition and I've included a suicide note on the wall borrowed from Virginia Woolf. It was really cathartic to paint.’

‘I just wanted to potentially offer comfort to someone who feels similarly to me’

Leonard Baby

By twisting the well-told Roman story, the artist hopes to dispel shame around mental health and the emotional scars queer individuals carry from repressive upbringings. ‘It's something that I have very strong feelings about,’ he says. ‘In America, we have not created a safe environment for people to talk about suicide or access help. Depression is really prominent in my family, a few of my sisters have dealt with it and so have I. I know for some people seeing this work might be triggering, but for me, exploring these subjects is really comforting. I just wanted to potentially offer comfort to someone who feels similarly to me.’

Leonard Baby, St. Agnes and the Future, 2025

As we end our call, the artist says he’s slightly nervous about sharing a body of work that’s so intimate, but that a weight has already been lifted by putting these feelings onto canvas. ‘It wasn’t a conscious decision to do this work,’ he says. ‘It just felt like something gnawing at me that was like, “These are the paintings that you have to paint.” It is scary but I'm just thrilled to present my sisters to the world. They are my favourite people. I already feel so much lighter and it's such a relief.’

‘The Babys’ is on view at Half Gallery in New York until 24 April 2025

See our guide to more New York art exhibitions to see this month

Orla Brennan is a London-based fashion and culture writer who previously worked at AnOther, alongside contributing to titles including Dazed, i-D and more. She has interviewed numerous leading industry figures, including Guido Palau, Kiko Kostadinov, Viviane Sassen, Craig Green and more.