The dynamic young gallerists reinvigorating America's art scene

'Hugging has replaced air kissing' in this new wave of galleries with craft and community at their core

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

If the idea of a design gallery conjures up images of a whispery white cube filled with plinths and prim collectors clutching their pearls, then it’s time you visited Tiwa Gallery on the fifth floor of a lofty Tribeca building, preferably for one of founder Alex Tieghi-Walker’s opening night dinners.

You’ll find a similar energy of ‘hugging, gossiping, kids and dogs’ at a Marta opening in Los Feliz, Los Angeles. Further up the Californian coast at Blunk Space in Point Reyes Station, JB Blunk’s daughter Mariah Nielson is keeping her father’s democratic spirit of make, do and blend, alive and thriving. And further north still, at Landdd in Portland, you can consider your collectible investments while participating in a sound bath or some flower arranging.

There’s a fascinating shift underway in America’s design gallery sector, proactively driven by a group of socially minded, enterprising young curators who value craft and community engagement as much as commerce. They are inspiring possible routes to market for an emerging generation of designers, and attracting new collecting audiences in their wake. It is, quite possibly, the most interesting development in America’s current design landscape, and there’s much that the rest of the world might learn from their attitudes towards connection.

‘Historically, in the design community, because of the necessary overheads required in owning and operating a gallery space, curators tended to show the work of established names with a guaranteed market to ensure they could pay rent and bills,’ explains design curator and consultant Sonya Tamaddon.

Sonya Tamaddon

Tamaddon is an alumna of LACMA, Timothy Taylor and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, and subsequently consulted with Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery and Tiwa Gallery, as well as the Mexico City- based gallery Masa. She was enlisted by Collectible, the dynamic young Belgian fair for contemporary collectible design, to helm the Curated section of emerging designers at its first New York outing last autumn to rapturous reviews. As a result, she is in hot demand as a gallery whisperer within design.

‘There’s been a shift away from white cube spaces, and a general desire for intimacy in design curation,’ says Tamaddon. ‘Spaces that look and feel like homes help people to engage with design, rather than seeing it as something inaccessible or remote.’ The idea of the gallery as a layered environment, more like a home than a museum, encourages a richer possibility for storytelling through programming, too. Liberated from the gallery catalogue and interpretation panel, young galleries can – and do – host workshops, panel discussions, readings and recitals, which all help to contextualise and enliven the work on show.

This leads to community building. The feeling is akin to hospitality more than the traditional transactional relationship between client and gallerist; the former, more formal hierarchy is melted into something far richer and more democratic between designer, curator and audience. As David Michon describes in his profile of Marta, below, hugging has replaced air kissing.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘When I began working with designers, many of the projects were juxtaposing art alongside design,’ Tamaddon says. ‘And there was a real discomfort in placing them together. What’s interesting to me is that now that the barriers between different disciplines have eroded, there is far greater dialogue and connection.’ Tamaddon describes the manifold ways in which such dialogue manifests, not just between designers and artists, but across generations and into native and ancestral roots; between designers and different cultural contexts and spatial environments; and between designers, gallerists and collectors, too.

‘There are a lot of collectors here with a great deal of imagination when it comes to contemporary design,’ notes Tamaddon. ‘In Europe, the depth of history means that people inherit furniture, and antiques carry a certain weight. I am a first-generation Persian-American citizen – I have nothing from Iran, and I’m not going to design my home with anything inherited. In the US, the legacy of heirlooms is not part of our consciousness to anything like the same extent as it is in other cultures.’

Liberated from the trappings of the art market and unencumbered by the dusty reverence towards antiques, the US collectible design market is blossoming, thanks to a vanguard of young curators that are driven by a passion for design and a belief in its narrative value, not just its commercial worth or investment potential. On the following pages, we introduce six galleries that we find compelling; each has a mission and a values-based agenda. Each has found a loyal and captive audience in a few short years since the pandemic receded. As Tamaddon concludes, ‘There’s a genuine excitement and a hunger for diversity within collectible design here in the US, connected by a generous, community spirit.’ Group shows and group hugs are the way forward.

Tiwa Gallery – New York

There’s always a project underway at Tiwa Gallery, the live-in exhibition space that Alex Tieghi-Walker runs on the fifth floor of a former factory building in Manhattan’s Tribeca. Like the artists he exhibits, who are usually self-taught and conceive of and fabricate their objects, Tieghi-Walker is hands-on and is learning as he goes. Recently, he installed a clawfoot bathtub, built a wall and spent a few weeks stripping paint from the window frames.

‘I’m a triple Sag,’ says Tieghi-Walker. ‘I get really restless, and I think I get very visually restless as well.’ The lived-in, ever-evolving nature of the gallery helps it feel human, which, in turn, makes it feel more approachable.

Along with his personal collection of antique furniture, quilts and ceramics, the space is filled with artefacts from previous exhibitions: Murano glass vases by Dana Arbib, a hand-carved chair by Minjae Kim, a silk and copper lamp by Cadis. A drop-in is more like paying a house call than visiting a gallery. ‘I like that it’s personal and intimate,’ Tieghi-Walker says. ‘The gallery is a real display of things in the world that interest me, and the values that are important to me.’ Those values include a respect for history, the natural world, and material exploration. But overall, a belief that craft is on par with the highest forms of art, as well as being an indispensable part of daily life for everyone. ‘This world is easier to access than you may think,’ reflects Tieghi-Walker.

Since its launch in 2021, Tieghi-Walker’s curatorial project Tiwa Select has continued to expand. It began as an online shop with Supreme-like drops of objects for sale, before morphing into a pop-up gallery in Tieghi- Walker’s former LA home, and then became a series of installations before its current incarnation. Over time, the sphere of Tieghi- Walker’s influence has grown, too. In 2023, he participated in a satellite exhibition of young galleries held during Frieze London, and next year, he’ll exhibit alongside more established design galleries, such as Friedman Benda. ‘I’m constantly learning about the design world, the art world, and seeing those patterns of how something goes from being a crafted object to a design object to an art piece. When does something stop being a crafted object and become a design piece?’ For example, the self-taught sculptor Vince Skelly was a musician and skater before he began making stools from salvaged wood; he now creates monolithic furniture pieces that are exhibited in galleries like Tiwa.

Right now, Tieghi-Walker is figuring out the right balance between staying hands on with artists, collectors and customers, and what comes next. ‘What I do is through instinct rather than thinking strategically – which might be my downfall at times – but I like the pace that I do things.’ He’s planned out exhibitions until the end of the year, including a solo show of Rich Aybar’s rubber and resin objects, but looking into the future, he’s more interested in group shows and a looser way of working. ‘I don’t have a big team to coordinate things,’ he says. ‘It’s very much me.’ Diana Budds

Landdd – Portland

Part gallery, part studio, part community space – Portland-based Landdd resists simple definition. Rooted in Latin American craft traditions and shaped by contemporary design sensibilities, it was founded in the embers of the pandemic by Lillian Hardy and Javier Reyes, at a time when people were craving community and connection.

Originally from rural Alabama, Hardy brings a background in art direction. Reyes, born in the Dominican Republic, runs the acclaimed Oaxaca-based design studio Rrres and works closely with artisans across Mexico. Together, the pair envisioned a space for shared creativity – a platform for artists and makers from the global south, as well as a setting for workshops and events focused on creative learning. At the time, in early 2022, commercial space was easy to come by, and the duo took on a disused ambulance repository in the city’s old town, which they then renovated themselves.

Today, the sunlit showroom hosts a rotating display of handwoven rugs, clay lamps and palm sculptures, all made using natural materials and traditional techniques with artisans from Oaxaca. But it’s the events calendar that has transformed Landdd from gallery to gathering place. From flower arranging and incense making to sound baths and live performances, these happenings have created a steady rhythm of community engagement and creative experimentation.

Over the past year, that rhythm has expanded outdoors. ‘A lot of people come to Portland because they want to be outside,' says Hardy. 'So it made sense to meet them there.' From forest walks to alfresco workshops, the move marks a natural progression, and has prompted Hardy to begin thinking of their work in two halves: in and out. Indoors, the focus remains on interior objects, storytelling and rituals. Outdoors, the practice is looser, more ephemeral, and often shaped by the seasons.

As well as striking a chord in their local creative community, Landdd's approach has recently caught the attention of some major US outdoor adventure brands that were drawn to its grounded aesthetic and values-led ethos. Still, the project remains intentionally small, independent and deeply intuitive. 'We never started with a business plan, says Hardy. 'We just keep responding to what feels human and honest.'

Research, travel and lived experience all feed into the products they design, make and sell, with Reyes in ongoing dialogue with the Zapotec weaving communities, and Hardy bringing a sensibility shaped by storytelling and identity. 'It's fundamental to us that when people see one of our textiles, they understand where it's coming from; that there's a connection there,' explains Reyes. 'If that's not transmitted, then it's just a textile. More than half its value is knowing where it's come from and how it's made.'

As Landdd looks ahead to its fourth year, its role is ever evolving – not as a gallery in the traditional sense, but as a living, breathing world of its own. Ali Morris.

Superhouse – New York

Stephen Markos, Superhouse NYC

Exhibitions at downtown New York gallery Superhouse, which Stephen Markos opened in 2021, draw from an eclectic group of artists and designers. Recently, this has included new and historic furniture by fine woodworking legends Tom Loeser and Wendy Maruyama; a terrazzo trompe-l’oeil pool table by up-and-coming studio Ficus Interfaith; and a glossy red vanity table from the 1980s by Elizabeth Browning Jackson. While the makers of these objects hail from different movements, disciplines and time periods, and are rarely exhibited together as a result, they share conceptual rigour, meticulous attention to craft and a boundary-breaking spirit. And finally, they are in conversation with one another.

Art furniture has had a long history in the US, though it has existed somewhat in the shadows compared to European movements. With Superhouse, Markos is bringing renewed attention to key figures, many of whom exhibited with the influential and under-acknowledged gallery Art et Industrie, which ran from 1977-1999 in New York. ‘It was our radical period,’ says Markos. ‘A lot of contemporary American artists owe what they are doing now to this vanguard from 45 years ago. And not a lot of galleries and institutions in the past 20 years have done much with the material.’

Through Superhouse’s exhibitions, Markos has placed work by these artists into major museum collections. The Art Institute of Chicago recently acquired a suite of works by Browning Jackson that were languishing in her barn; the Museum of Fine Arts Boston purchased an early carved lamp by Maruyama, one of the few women in fine woodworking; and a totemic lamp and jewellery box by Alex Locadia (a Black artist from Brooklyn, who exhibited at Art et Industrie, but wasn’t embraced by his peers) went to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. And earlier this year, Markos exhibited a series of works by Dan Friedman, a graphic designer who began a furniture and sculpture practice a few years before he died due to complications from AIDS in 1995, and brought them into important private collections. ‘I don’t mean it to sound grand, but it’s righting the wrongs of the past,’ Markos says.

And he’s also making sure that thrilling contemporary artists don’t experience the same outcome. Superhouse recently helped a stool by Kim Mupangilaï, a Belgian- Congolese artist who explores her identity and lineage through furniture, to enter the Vitra Design Museum collection.

This autumn, the gallery will host a debut solo show of sculptures by Colin Knight, a Virginia-based artist who explores the intersection of historical conflict and design. ‘Having diversity of voices is really important to me,’ notes Markos. ‘Whether it’s people that are further on or younger in their careers, who come from different backgrounds, or who work in different materials – the main goal is the quality of the work and the perspective that each artist brings.’ Diana Budds.

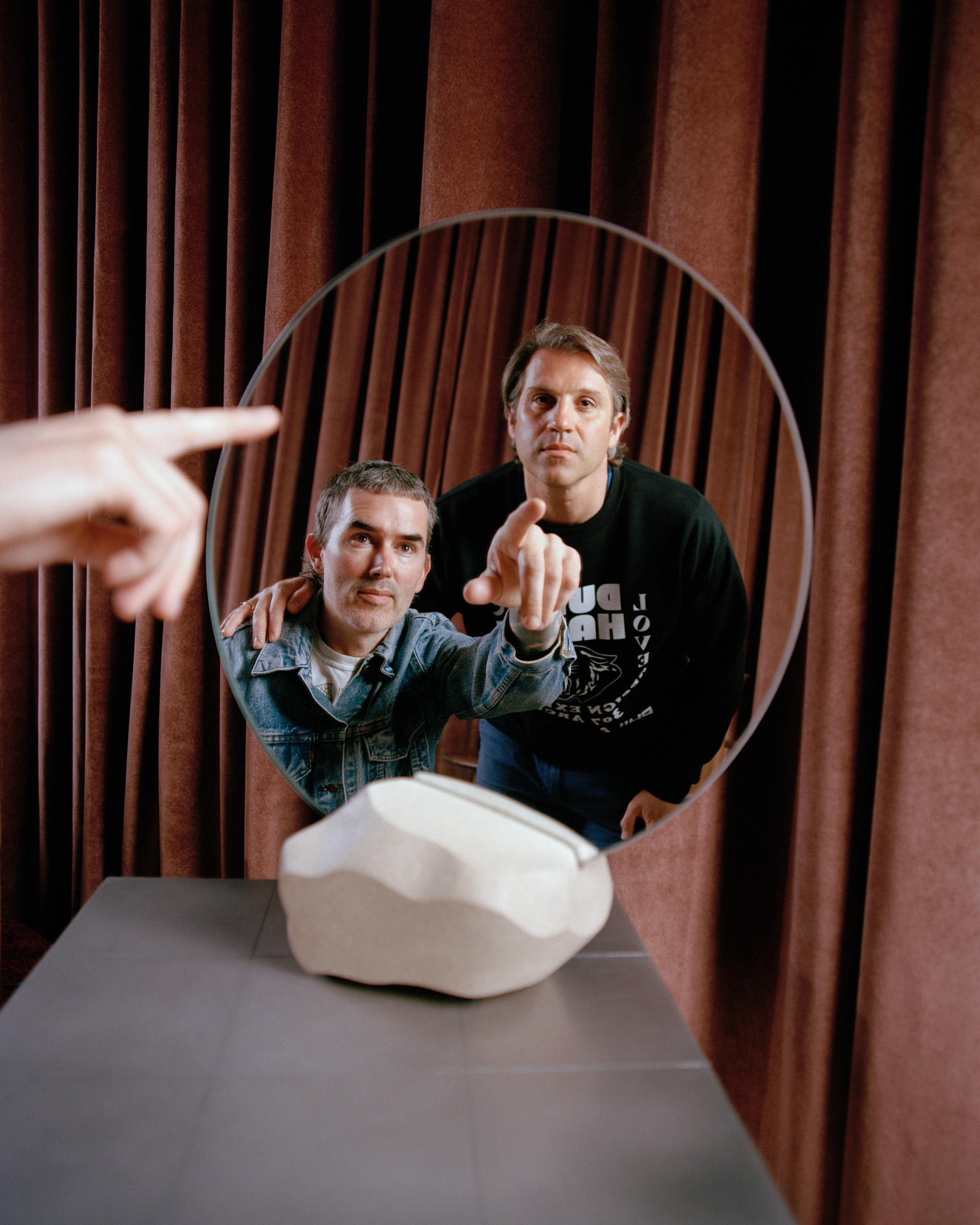

Dudd Haus – Philadelphia

Stepping into Dudd Haus, which opened in downtown Philadelphia earlier this year, is like entering a Lynchian Black Lodge for design. Heavy crimson curtains line the walls of the narrow room, which is decorated with a black-and-white chequerboard floor and a mural of snowy mountains. But the space’s inhabitants aren’t Dale Cooper and Laura Palmer; they’re a cabinet made from melted plastic bags and beer cans by Chen Chen & Kai Williams; a steel and glass table lamp with an iridescent finish loosely based on an acid trip by the Montreal-based designer Jean-Michel Gadoua, and a puzzle- like bench by the UK-based woodworker James Burial, among dozens of other fascinating objects that all sit comfortably in the blurry intersection of art and design.

‘I love the feeling of going into an antique store where you have the opportunity to just take yourself on a journey and find things,’ says the gallery’s co-founder Chris Held, who also founded Jonalddudd, an itinerant New York Design Week curatorial project that began ten years ago to create space for designers to exhibit experimental, often irreverent, work. To wit: a wood chair coated in crushed eggshells; a floor lamp sculpted from papier-mâché embedded with flowers; and the screws and bolts that hold a table together presented like jewels in a treasure chest were part of Jonalddudd’s installations this year. It’s the type of conceptual work that makes design curators salivate.

‘We’d all love to be selling these weird things because it would make our lives easier, but the purpose of someone producing the objects we typically show at Jonalddudd is to be outside the monetary system that we’re all forced to operate under,’ Held says. ‘That to me is really punk and I love the spirit of it.’ Over time, the exhibition became larger, as did the community of people around it. There was a sense among the collaborators that it should last longer than a week, hence the opening of a permanent gallery.

Everything in Dudd Haus is for sale – designers still need to keep the lights on, after all – but there’s a sense that the gallery is more about keeping a renegade spirit alive (for the makers of the objects, as well as for the people who appreciate them) than it is about cashing a cheque. The gallery is structured like a cooperative, with different tiers of membership included on its website and/or in the gallery. Additionally, the gallery takes sales commissions at a lower rate than typical dealers. The roster includes established figures who have successful businesses but want to try something different, and emerging practices that might not have gallery or retail representation.

‘There’s a huge benefit for a new, up- and-coming designer to literally share a space with a Steven Bukowski,’ says Charles Constantine, founder of furniture company Bestcase, co-founder of Dudd Haus and an organiser of Jonalddudd. ‘And that road goes both ways. If you’ve had a practice for a while, it’s nice to be in a position where you can talk to someone who has a newer, fresher point of view.’

Blunk Space – Marin County

The chainsaw was, and really does remain, a pretty badass tool for art. It was JB Blunk’s tool of choice and, even without knowing much about him, it immediately places him ‘out in nature’, somewhere with big trees. And he was: in this case, Marin County in Northern California. Many, many sculptural works in wood later (as well as ceramics and paintings), the impetus for his first chainsaw purchase is now one of his most important legacies: his home.

It’s hard to separate the idea of Blunk the man from Blunk the place. That home, on a hillside in Inverness, wasn’t just where he lived – it was his greatest artwork. Every door handle, every stool, every post and beam bears the imprint of a mind tuned to that material. It’s still mainly as it was, but now it’s occupied again by his daughter Mariah Nielson, who spent her childhood there, sometimes loving it, sometimes hating it, and now back to loving it.

Nielson understands legacy as precious few do; it’s not about freezing something in time but keeping something alive, active. Hence Blunk Space: a gallery, studio space, and at-times residency established in 2021 in nearby Point Reyes Station.

‘Gallery’ is also a very active concept in the Blunksphere. ‘It was an exhibition,’ Nielson puts it simply, ‘that changed my father’s life.’ In fact, you can sort of plot out the life of JB Blunk through a series of key shows. The first was an exhibition of mingei (Japanese folk art) at Scripps College, in Claremont, California, visited in the mid-1940s as an university student, which convinced Blunk to become an artist. Then, there was an exhibition of his own work at Tokyo gallery Chūō Kōron in 1954 (it was organised by Isamu Noguchi after they met checking out some mingei in Tokyo in 1952, and it helped Blunk pay for a return flight home to the US after three years in Japan). And now, posthumously, it’s Blunk Space.

What Nielson does isn’t about commerce, really (almost none of the best things in this world are). Instead, it sort of mirrors her father’s experience: it’s about ‘encounter’ – both between a person and a space (because ‘a place is always a part of a story,’ says Nielson, and Inverness has its impact), and between one person and another.

A Blunk Space exhibition, as a result, is most often not a ‘solo’ experience – it’s an ‘and’: Martino Gamper and Adam Pogue; Rio Kobayashi and Fritz Rauh; Solange Roberdeau and Jochen Holz; Rick Yoshimoto and Charles de Lisle; Rachel Kaye and Jay Nelson – you get the point. Nielson is, in this sense, not at all a ‘curator’, but a convenor – and that’s better. As much as she’s an access point and guide into her father’s world, she also delights in getting out of the way. Perhaps the worst way to manage a legacy is to try too hard to control what that legacy is, and Nielson doesn’t. Instead, in true Californian spirit, she lets some forces bigger than any individual take over – just as they had done for JB Blunk: nature, coincidence and chemistry. David Michon

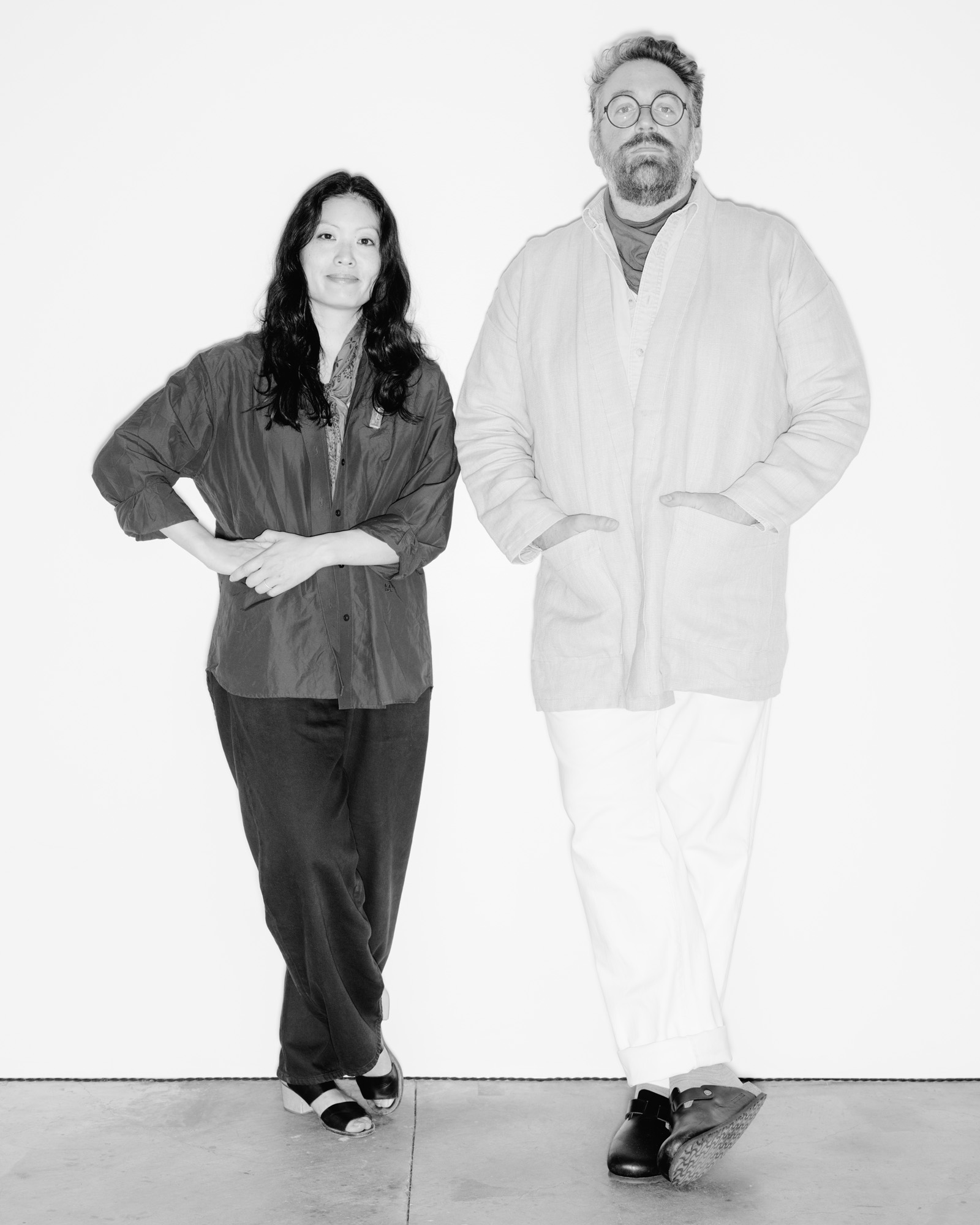

Marta – Los Angeles

It’s not always the case that, when you attend a gallery opening, the ‘regulars’ also include any number of artists from past shows. But, the set at Los Angeles gallery Marta does. Somehow, unintentionally, they’ve tapped into an ‘inevitable community’, speeding up connections in a centreless, wide, flaky LA where social circles grow at a slow pace. Their openings, as a result, feel akin to a house party – a lot of hugging, gossiping, kids, dogs and, if you’re lucky, a spontaneous dinner at Speranza nearby. Air kisses are taboo.

It’s been like this ever since they were at the now-called Little Marta, a small space on the Echo Park stretch of Sunset Boulevard at the front of co-founder Benjamin Critton’s former graphic design office, where the gallery first opened in 2019. His partner in work and life, Heidi Korsavong, comes from an art history and interior design background – she zhuzhed the space and got it ready for its ‘gallery’ life, with some gardening help from friends, local landscapers Terremoto.

Marta upgraded in 2023, and the new Los Feliz space is much bigger, double-height, and even has a small, mostly secret studio apartment for visiting artists. Nifemi Marcus-Bello just stayed, in town from Lagos for the third act in a three-part series shown by Marta (and being collected into a book to be published by Apartamento later this year). Critton and Korsavong moved from

New York in 2016 (though Korsavong is from Southern California), and they’ve shown back there a few times, including an exhibition of toilet roll holders, co-curated with Emmanuel Olunkwa. Another, with auctioneer Catalog Sale, paired archival chairs with some wacky new ones made by a series of designers in just three days.

But Marta’s character is found in its California-ness: free-spirited, label-adverse, earthy and unpretentious, even if a little brainy when you dig in. ‘Integrity’, says Korsavong, ‘rewards over time.’ Why wait though? In just six years, the Marta community is already an obvious legacy.

Everything about Marta feels as if it’s about ‘home’ – being one, and imagining art and design in it. Back at Little Marta, in 2021, there was a show of mesmerisingly simple, paint-splattered artists’ benches saved from a junk pile at the shuttered MacArthur Park campus of the Chouinard Art Institute by Corinne Hartley, an alumna, in 1972. That’s very specific! And, non-commercial. But, ‘it was an access point to LA,’ says Critton. ‘People kept saying, “You know who else went there? Mary Corse! Ed Ruscha!” You start to understand the network and how the foundation of LA as an artistic city was laid.’

Again (and again, unintentionally), Marta seems all about surfacing not just ‘an artist’, but something more social. It helps you make sense of what any of this (the works at Marta) has to do with any of that (the LA around you). Even when the artist has come over from Nigeria, somehow Marta softly makes it speak to the home that is here. And with the politics of America right now, it’s an important talent. David Michon.

Hugo is a design critic, curator and the co-founder of Bard, a gallery in Edinburgh dedicated to Scottish design and craft. A long-serving member of the Wallpaper* family, he has also been the design editor at Monocle and the brand director at Studioilse, Ilse Crawford's multi-faceted design studio. Today, Hugo wields his pen and opinions for a broad swathe of publications and panels. He has twice curated both the Object section of MIART (the Milan Contemporary Art Fair) and the Harewood House Biennial. He consults as a strategist and writer for clients ranging from Airbnb to Vitra, Ikea to Instagram, Erdem to The Goldsmith's Company. Hugo recently returned to the Wallpaper* fold to cover the parental leave of Rosa Bertoli as global design director, and is now serving as its design critic.