Edgar Martins’ photobook shows prisoners fear of being forgotten – by not showing them

The twin-publication What Photography & Incarceration have in Common with an Empty Vase reveals a new dimension to British prison HM Birmingham, its inmates and their families

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

In the midst of Edgar Martins new photobook lies a photograph of a note, written in pencil. It reads: ‘Adrian & Carmen, husband & wife, need help. Adrian can do massage, gardening, reflexology, any kind of chores. Carmen can take care of children, old people, pets. She can sweep, brush, water the plants, teach English. We are ex-offenders but reliable, hardworking, punctual serious, friendly and good. We live close, at a friend. Please call: 07728 610 415. Thank you.’

Martins’ monograph, titled What Photography & Incarceration have in Common with an Empty Vase, and currently exhibited at Lisbon’s Galeria Filomena Soares, explores what prison does to a prisoner. But Martins has not photographed inside the prison walls. Instead, he has create a series of photographs that mediates on the impact and consequences of incarceration on the inmate – without ever showing us the person behind bars.

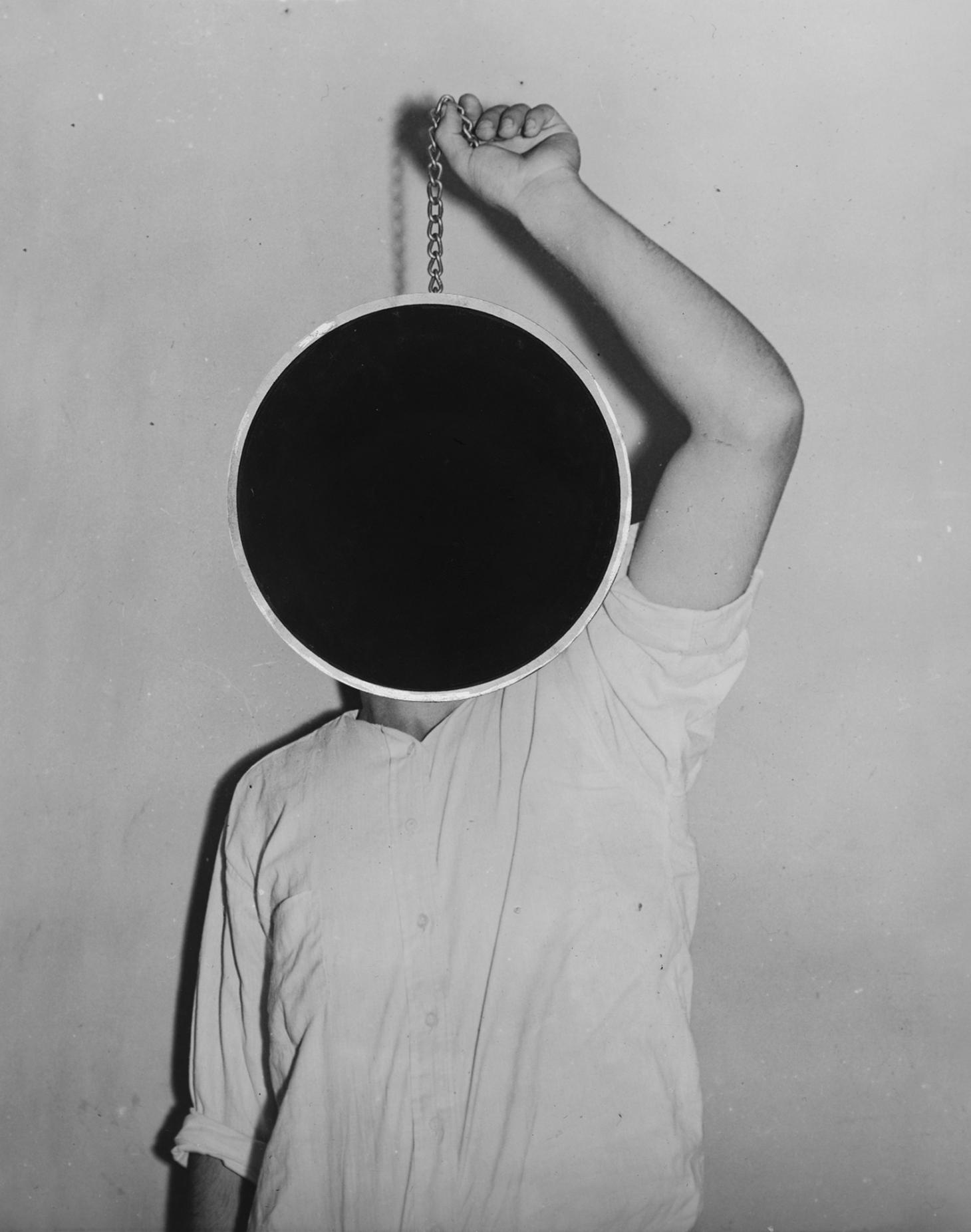

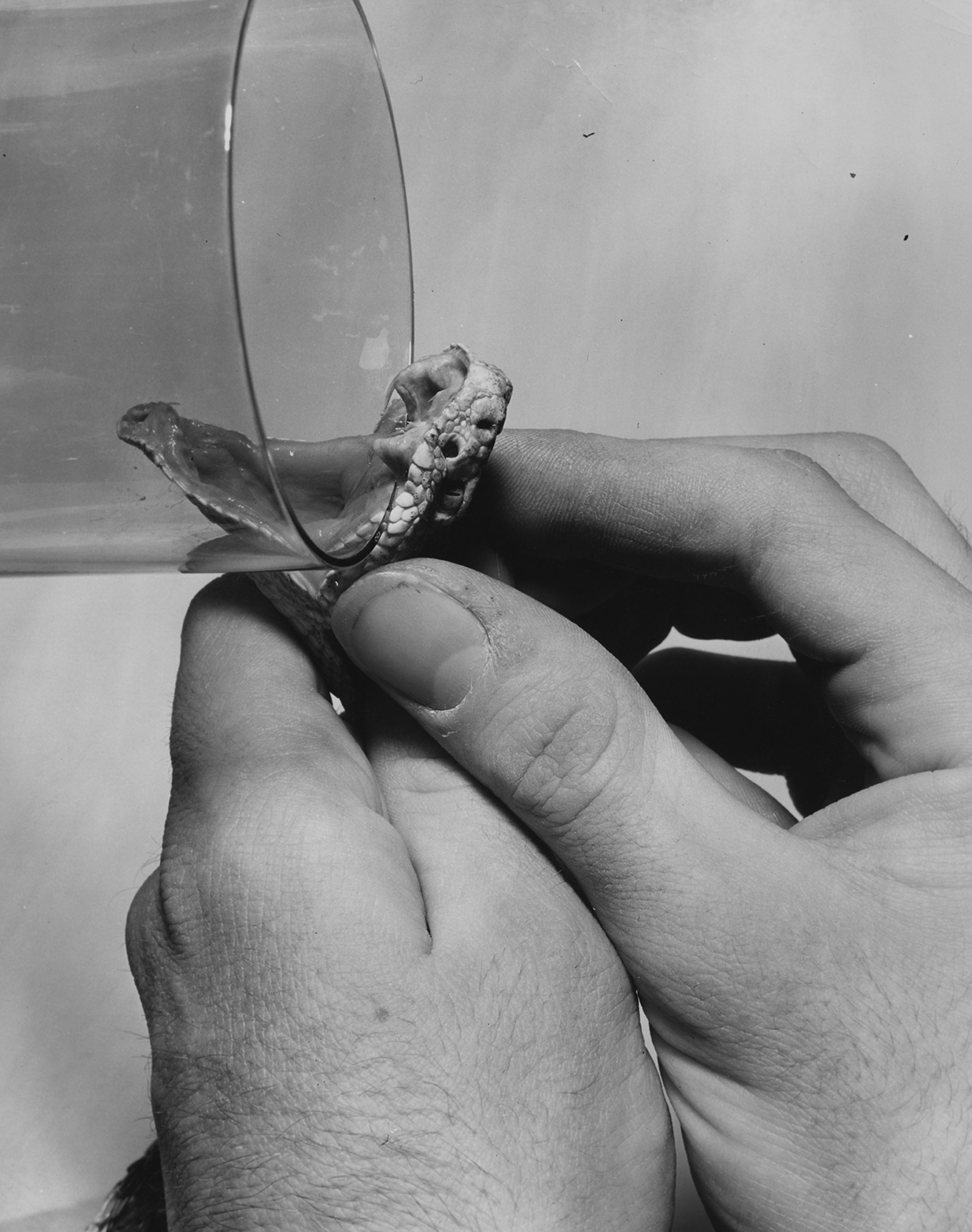

In doing so, Martins has assembled a series of pictures pictures that, at first glance, avoid easy understanding. The pictures appear to be ephemera; deserted monochrome streets, still lifes, photographs of postcards showing faraway scenes, an archival tableaux that could be the fragment of a bad dream. The Portugal-born artist ensures we know little about these pictures. We are not told where and when they were taken, or what or who is being pictured, or what relevance they have to the prisoners he worked with.

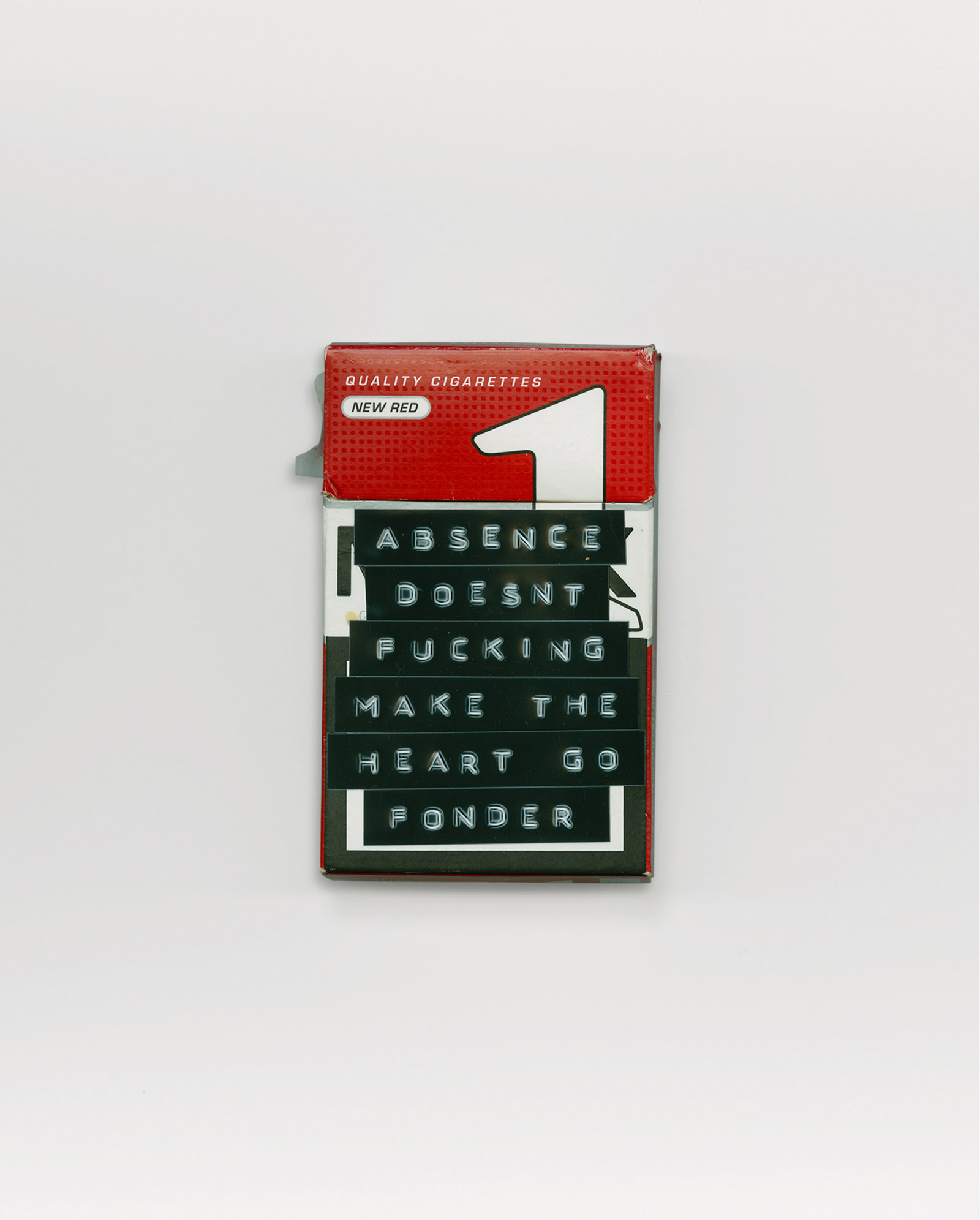

But, after time, the pieces start to fit together: a pair of tiny pink ballet shoes with ‘Daddy’s Girl’ inscribed on the toes; a pencil with ‘Let It Go’ written on its flank; an old Nokia cellphone with the screen reading ‘4give me ma’ in text. There is prison bureaucracy – a letter telling of drug seizures, and a letter sent home entirely redacted in black. There’s a pack of cigarettes adorned with ‘Absence Doesn’t Make the Heart Go Fonder’ in typed font. Some photographs show what we assume are the tall prison walls, taken from the outside.

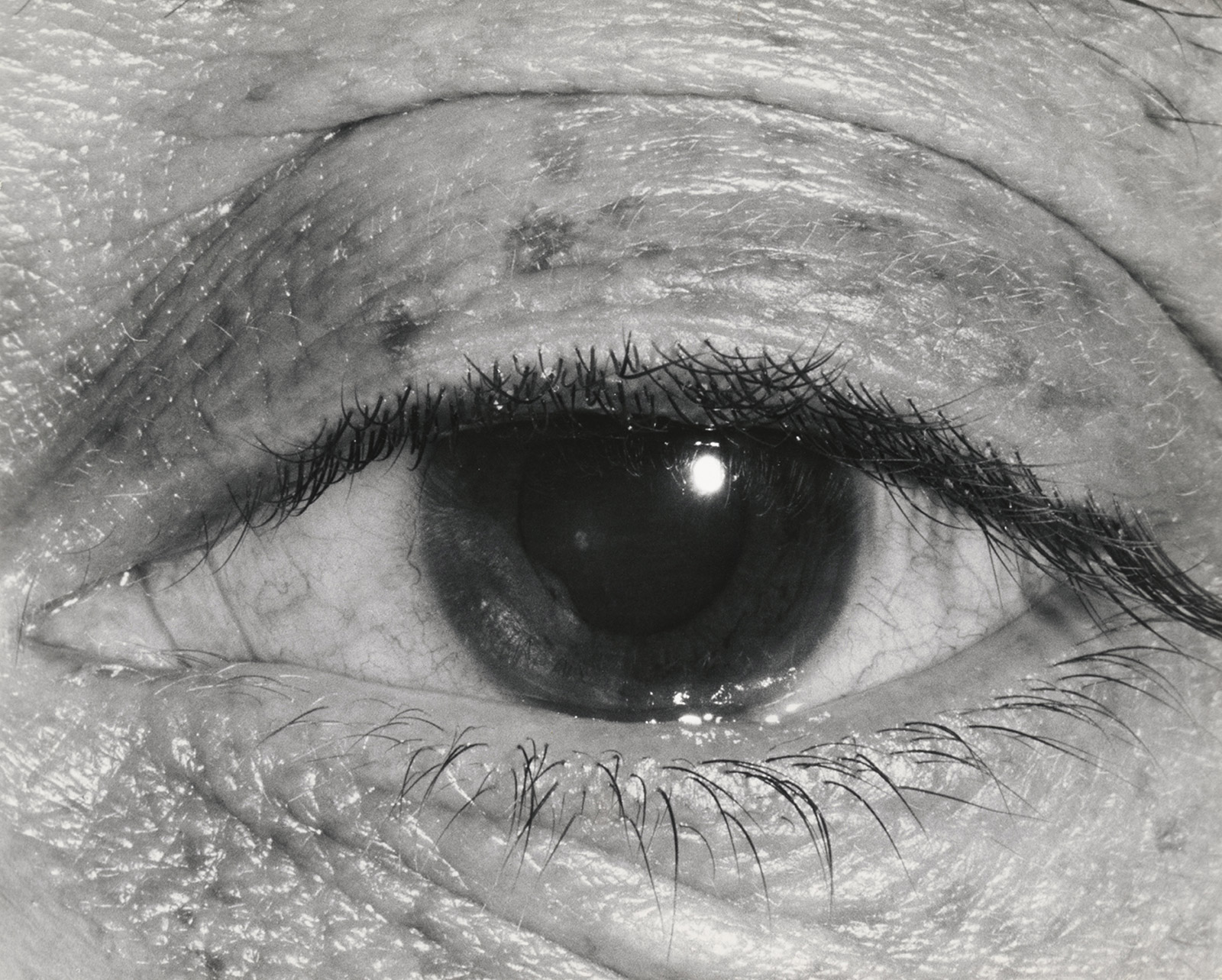

Martins also includes unflinching portraits of teenage girls and boys who, we assume, are the children of those kept inside. Some are bleeding, or have facial wounds – a visual manifestation of a lingering violence that, in many cases, has been handed down through generations. He describes the project as ‘a series about how people deal with being inside, and how people outside deal with their loved ones being inside’.

The series was commissioned by Grain Projects, an arts organisation supported by Arts Council England and Birmingham City University, and focused on HMP Birmingham, a remand prison referred to locally as Winson Green. The prison holds inmates awaiting trial and sentencing, alongside those serving sentences of up to 20 years. The prison has also caused some controversy: from 2011 to August 2018, it was managed by the security firm G4S before coming under state provision again after the private company lost its contract permanently.

The book is the result of several years of engagement with the prison, and with the slow development of relationships with prisoners serving some of Winson Green’s longest sentences, made possible by Martins’ ability to work closely with numerous family liaison officers. The artist had to work hard to gain access in what he describes as a ‘very dysfunctional’ system. Winson Green saw four different directors come and go in first three years Martins spent working on the project, which stymied his ability to work on the project.

Over time, he built rapport with a convicted drug trafficker who had recently turned 50, and who kept a diary of his life behind bars, written carefully and eloquently in simple lined notebooks. Martins remembers reading the diary from front to back. It began with the inmate expressing his frustration at how his sentencing has been delayed and ends with him worrying that the people outside are forgetting about him.

The man told of his relationship with his two children, his anxiety for the future, his boredom and despondency behind bars, his training with the Samaritans to be a listener, and his thoughts on other prisoner’s willingness to self-harm. It would have been easier, maybe, to create a traditional documentary story of this man’s life. Yet Martin has used his words to create a series that works along the lines of suggestion and situation, of metaphor and allegory.

Shown together, Martins’ images grow into piercing portraits of a person made unseen by society’s judgement of the greater good. And by rejecting the most obvious human touchpoints – of not allowing us to look at prisoners’ faces, to read their expressions, to search for an understanding – Martins provides a deeply troubling portrait of absence. He is showing by not showing. And that is the point: the terrifying invisibility of confinement.

INFORMATION

What Photography & Incarceration have in Common with an Empty Vase, £60, published by The Moth House. A touring exhibition of the work is on view at Galeria Filomena Soares, Lisbon, until 4 March; the Macau Museum of Art, 31 July – 7 November; Three Shadows Photography Art Centre, Beijing, December – March 2021; Geneva Photography Centre, March 2021; Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Lisbon, July 2021; and MOCA London, October 2021. edgarmartins.com

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.