Anicka Yi fills Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall with science, scent and intrigue

Anicka Yi has let loose a family of floating AI jellyfish in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. We spoke to the artist as she prepared for her scent and science-infused Hyundai Commission

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The work of the Korean-American artist Anicka Yi takes in science, microbial activity and air-carried markers of identity, amongst other things. The perfect pick, then, for Tate Modern’s first Turbine Hall commission (officially the ‘Hyundai Commission’) since Covid closed operations.

The commission is Yi’s largest and highest profile to date – and art commissions don’t come much larger and higher profile – but Tate Modern’s enforced closure at least gave her a good run at it. She’s been working on the installation for the last two years, a process she calls a ‘radical voyage with no roadmap’ and a journey she admits was as personal as creative. ‘There was so much transformation of every facet of the project, internally, externally. And it's a radically different project than the one we would have produced had we opened last January, or last October, as we were originally slated to do.’

When we talk, Yi is still at work on site. Details of the installation don’t stretch much beyond the fact that it will somehow touch on science, scent and artificial intelligence and Yi can’t get into specifics yet (since the interview was conducted, we have discovered this involves a series of levitating robots powered by helium and AI). She’s clear the commission, titled In Love With the World, has been a huge challenge, on multiple fronts.

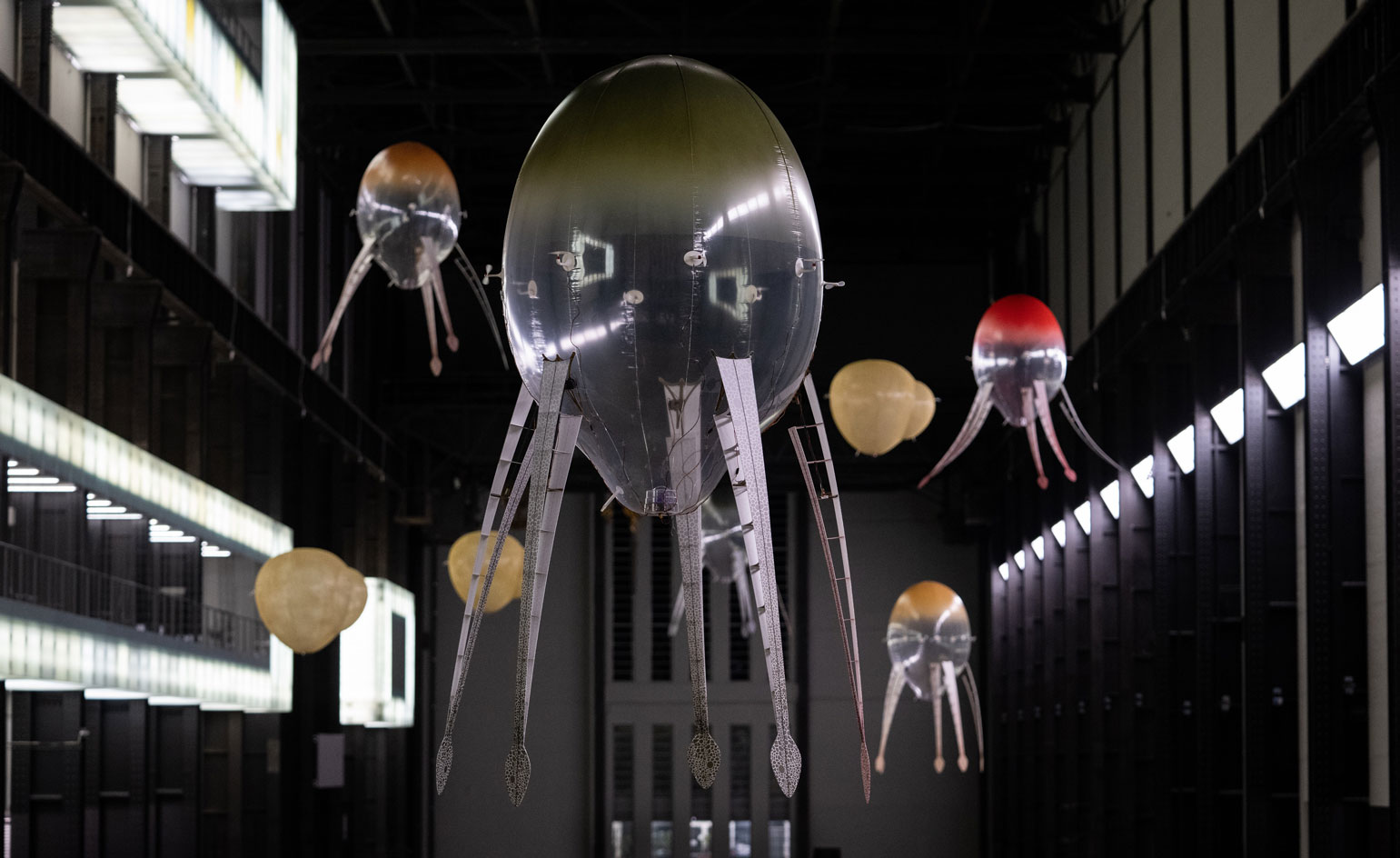

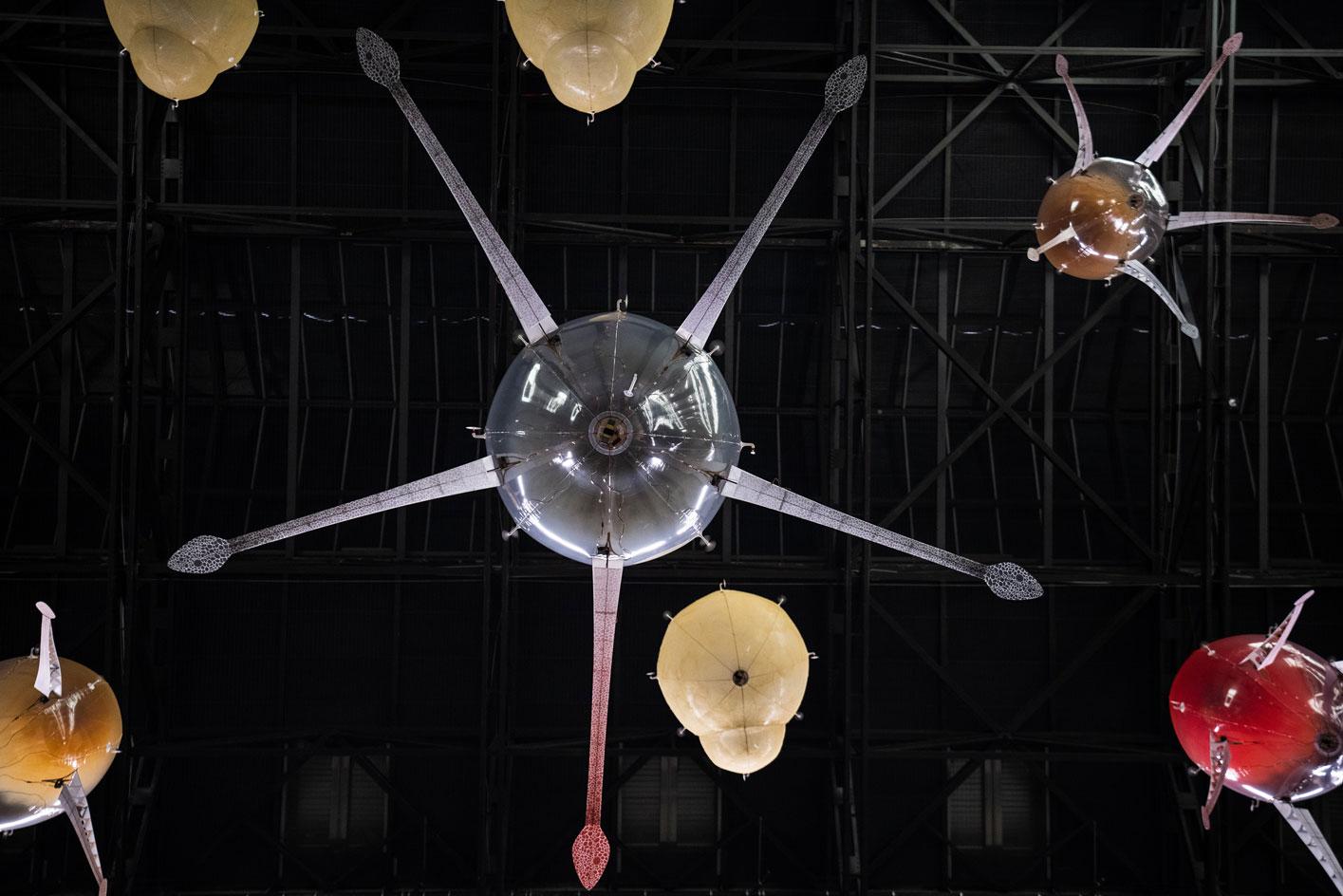

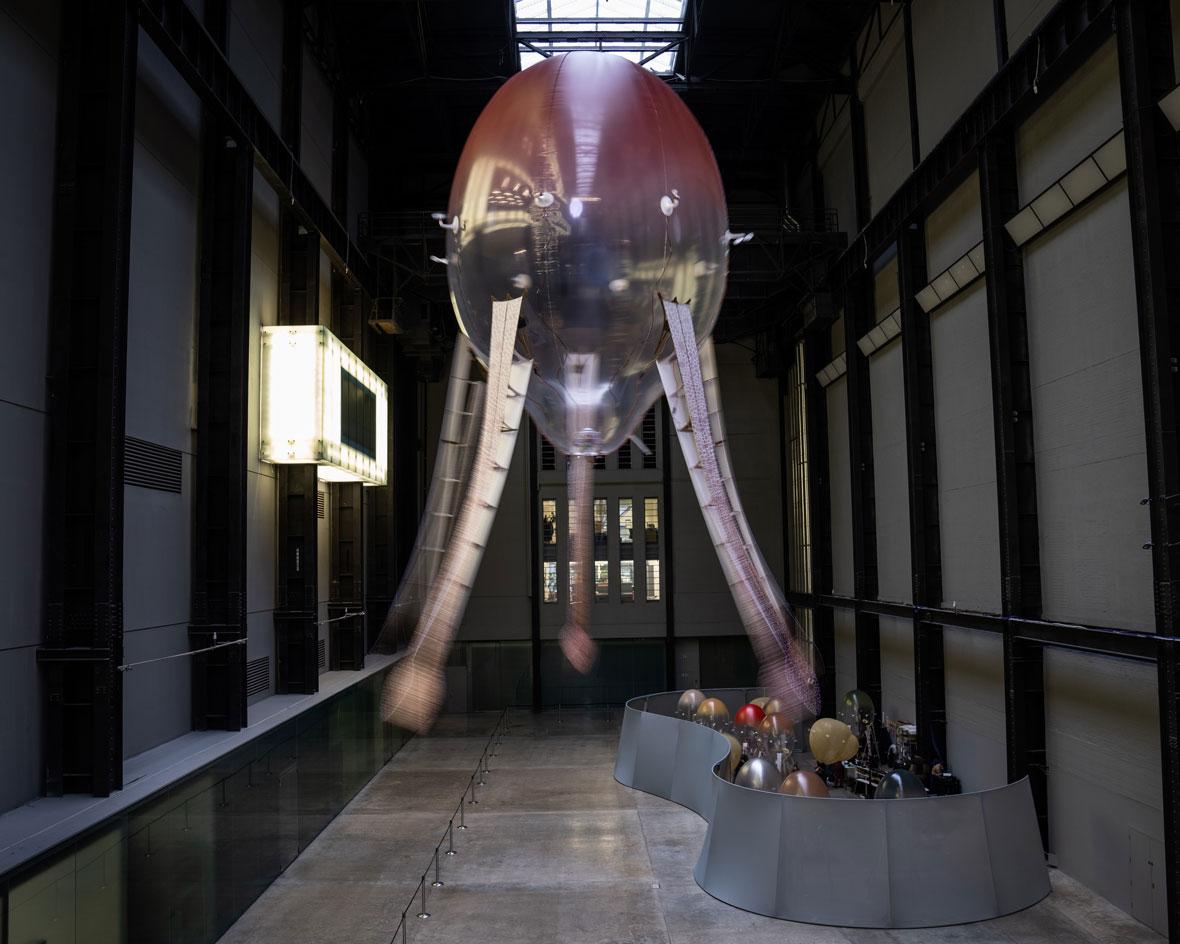

Installation view of Hyundai Commission: Anicka Yi: In Love With The World at Tate Modern, October 2021.

Tate Modern is the most visited space for contemporary art in the world and previous Turbine Hall installations, from Anish Kapoor’s ten-storey trumpet through Carsten Höller’s slides, Ai Weiwei’s seeds, Olafur Eliasson’s artificial sun and Kara Walker’s giant fountain, have redefined the possibilities of popular public art. It’s a daunting legacy to deal with. There’s an inevitable pressure to create a huge, accessible spectacle and the trick for the Turbine Hall artist is arriving at something that works for that vast, awkward and ambiguous space.

For Yi, there is an extra level of pressure. This is her first public art project of any size. ‘The hardest part is really getting over your fear and anxiety about the wild unknown of the public,’ she says, only half joking. ‘In a gallery or a small museum, it’s a very controlled environment. Here it just feels so lawless, [there’s] so much mayhem and chaos. And now I’m on site, it’s no longer abstract, or on Zoom and spreadsheets and Word documents. I’m interfacing with the public and I'm thinking, “Oh my lord, they’re a living, breathing entity.”’

‘In a gallery or a small museum, it’s a very controlled environment. Here it just feels so lawless, there’s so much mayhem and chaos’

The timing and place of the commission have encouraged a new kind of generosity and legibility. ‘I think it's almost impossible to enter into the project without thinking about the loaded vastness of the space and what all of that entails. But luckily you have time to figure out your relationship to that. For me, it meant that I wanted to be exceedingly generous to the public in a way that I never have. I’ve had a very trepidatious, anxious relationship with the audience, but this project was almost like a gift to them. I reserve very little for myself. In past projects, it’s been more hermetic, codified but this is an unvarnished, unfettered sort of coming out.’

Now 50, Yi was born in Seoul but her family moved to Alabama when she was two. Her mother worked in biomedicine and had a passion for fragrance. Yi moved to London in the early 1990s, working as a fashion stylist and copywriter before moving to New York later in the decade and becoming friends with the fashion and art collective, the Bernadette Corporation.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Unsure of her calling, Yi tentatively committed herself to art, working with unusual materials and, picking up on her mother’s passion, set on sculpting with scent. Yi was determined on reversing the marginalisation of the olfactory senses in art and unpacking the cultural baggage of scent and the tight bundling of smell, misogyny and racism, what she calls the ‘bio-politics of the senses’.

She didn’t have her first solo show until 2011 but that year’s Convox Dialer Double Distance of a Shining Path, a pungent soup of powdered milk, antidepressants, palm tree essence, shaved sea lice, and ground Teva sandal dust, was a signal of intent. She also began collaborating with scientists and technologists (she describes her art as a kind of techno sensualism) and in 2014 – 15 was a visiting artist at the MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology.

Installation view of Hyundai Commission: Anicka Yi: In Love With The World at Tate Modern, October 2021.

Her creative adventures in material science have seen her work fermented kombucha into leather, create tempura flowers, and inject live snails with oxytocin. In 2015 she asked 100 female friends and colleagues for swab samples from orifices of their choice, used the samples to grow bacteria in petri dishes, and analysed the results to create a chemical fragrance, released at an exhibition called ‘You Can Call Me F’.

She developed the idea a year later with ‘Life is Cheap’, collecting swabs exclusively from Asian-American women to grow bacteria on Plexiglas tiles, showing them alongside thousands of carpenter ants, a complex commentary on female labour and networks again set within a scent-scape of her own creation.

In 2019 she created two pieces for the Venice Biennale. Biologizing the Machine (tentacular trouble) featured animatronic moths flying inside giant lanterns made from kelp. For Biologizing the Machine (terra incognita), meanwhile, she developed a light-based language from bacteria.

Yi’s art, then, is smart, complex and heavy on the concept. Yi says there will be smell and there will be ‘entities’ at the Turbine Hall and all the conceptual density you would expect of her work. ‘It's been driven by the philosophical and theoretical, objectives, questions and interrogations.’ But she insists the installation will also provide an instant experiential hit. ‘This is so experientially driven, you don't need all of this sort of backstory.’

The show includes ‘advanced algorithmic machines’, she promises, technology far more ambitious than the animatronic moths that fluttered to life in Venice. And there is nothing fictive or sleight of hand about it. ‘There’s no screen door that you can use to pretend you did this while you were actually doing something else. It’s actually doing what we say it is doing and I’m really proud about that.’

Installation view of Hyundai Commission: Anicka Yi: In Love With The World at Tate Modern, October 2021.

Yi and the Tate team have been testing out elements of the work with the public and Yi has been surprised and somewhat de-centred by the strength of reaction. ‘There is a tremendous amount of feeling and it's very destabilising for me. I thought, “Oh my god, how do rock stars absorb all of that energy and emotion?” I'm by no means up there, but I've never experienced anything like this before and I don't know how you prepare for it.’

Ultimately, she hopes she has created a new kind of public experience. ‘I really hope it foregrounds how porous we all are and that what you experience is not as a monolithic public but a microcosmic, granular experience that is very overpowering.’

Yi’s larger goal has always been to unroot and relocate us within nature, to sensitise us to different kinds of connections. ‘We think that we have vanquished nature, that we are separate from it and let all other lowly beings, animals, plants and microbes, deal with scent. That’s why scent really, really bothers human beings, because it ties us to the natural world.’

Fittingly, for a high-concept, big-impact post-Covid exhibition, Yi’s key material in the Turbine Hall is the air we breathe. ‘We're all immersed in it, we have to share it. It reminds us that we're all genetically linked, that we are all interdependent and that there is no real beginning, middle, or end. The air we are breathing now still contains atomic nuclei from the fires that burned Joan of Arc.’

Ultimately, she is asking us to breathe in and think again. Think hard. ‘All of these scientific and philosophical certainties are starting to crumble. We need to actually come up with new ideas and update every facet of human engagement, culture, philosophy, technology, all of it.

INFORMATION

’Hyundai Commission: Anicka Yi’, 12 October 2021 – 16 January 2022, Tate Modern, tate.org.uk