V&A East Storehouse is a new London museum, but not as you know it

Designed by DS+R, the V&A East Storehouse immerses visitors in history as objects of all scales mesmerise, seemingly ‘floating’ in all directions

Museum displays are typically the tip of a collection’s iceberg, but this is neatly turned on its head at the new V&A East Storehouse in London. The Victoria and Albert Museum family’s newest outpost opens at Here East in May, as part of East Bank on Stratford’s Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park – neighbouring institutions include Sadler’s Wells East and the upcoming V&A East Museum (set to open in Spring 2026). Part of a growing cultural hub, the Storehouse, designed by New York-based architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R) with support from UK-based architects Austin-Smith:Lord, is also a pioneering statement in museum storage; as crossing its threshold is not only a deep dive into the celebrated institution’s vast and incredibly varied holdings but also offers unprecedented public access to all its treasures. In short, this is a museum, but not as you know it.

The new V&A East Storehouse in London

Formerly the broadcasting centre for the 2012 Olympic Games, the building that contains the Storehouse is, from the outside, a relatively opaque, minimalist shell. The V&A occupies part of it – sharing it with Studio Wayne McGregor, UCL among others. It is embedded discreetly within the Here East volume, with no external exposure except for an area on the ground floor containing four creative workshops, a café and a flexible, informal entrance lobby. DS+R principal David Allin explains the studio’s strategy for this fairly inward-looking commission: ‘Rather than the conventional layering of public and private spaces, where the most public programmes line the perimeter and the most private areas sit in the centre, we flipped that diagram. We imagined filling the entire internal volume with storage, optimised for efficiency and density. Then we carved out a central space, with a route connecting to it from the outside. This inner sanctum would be the most public part of the building. Around it, concentric rings would get progressively more private as you reached deeper and deeper into the storage.’

This hidden treasure of a space aptly echoes its content – the V&A’s rich collection, which spans from glassware and ceramics to furniture and entire building elements or rooms. The new, purpose-built interior is home to some 250,000 objects, 350,000 books and 1,000 archives. This includes spectacular architectural moments such as a section of Robin Hood Gardens, the now demolished, important 1960s brutalist architecture example by architects Alison and Peter Smithson; a Frankfurt Kitchen, the 1926 design by Austrian architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, a forerunner of today’s fitted kitchen and an important point in domestic design; and the medieval Torrijos ceiling from a now-demolished Spanish palace, reconstructed in situ and unfolded in full glory.

The piece’s move here from their past storage at Blythe House was important in terms of their preservation and storage conditions but also made keeping them in London possible, explains Tim Reeve, deputy director and COO at V&A. A critical aspect – built in from the project’s inception – was the vision of a strengthened relationship between the museum’s holdings and the public, he says: ‘V&A East Storehouse is designed as a free, self-guided cultural experience – opening up the full magic and majesty of museum life – even as it is where we store and care for our collections and archives. To the extent that objects are displayed, they are displayed as stored, lightly curated, with visitors and objects sharing the same oxygen, the same physical space. It's about browsing, looking hard at objects and making connections between them that resonate and inspire our audiences.’

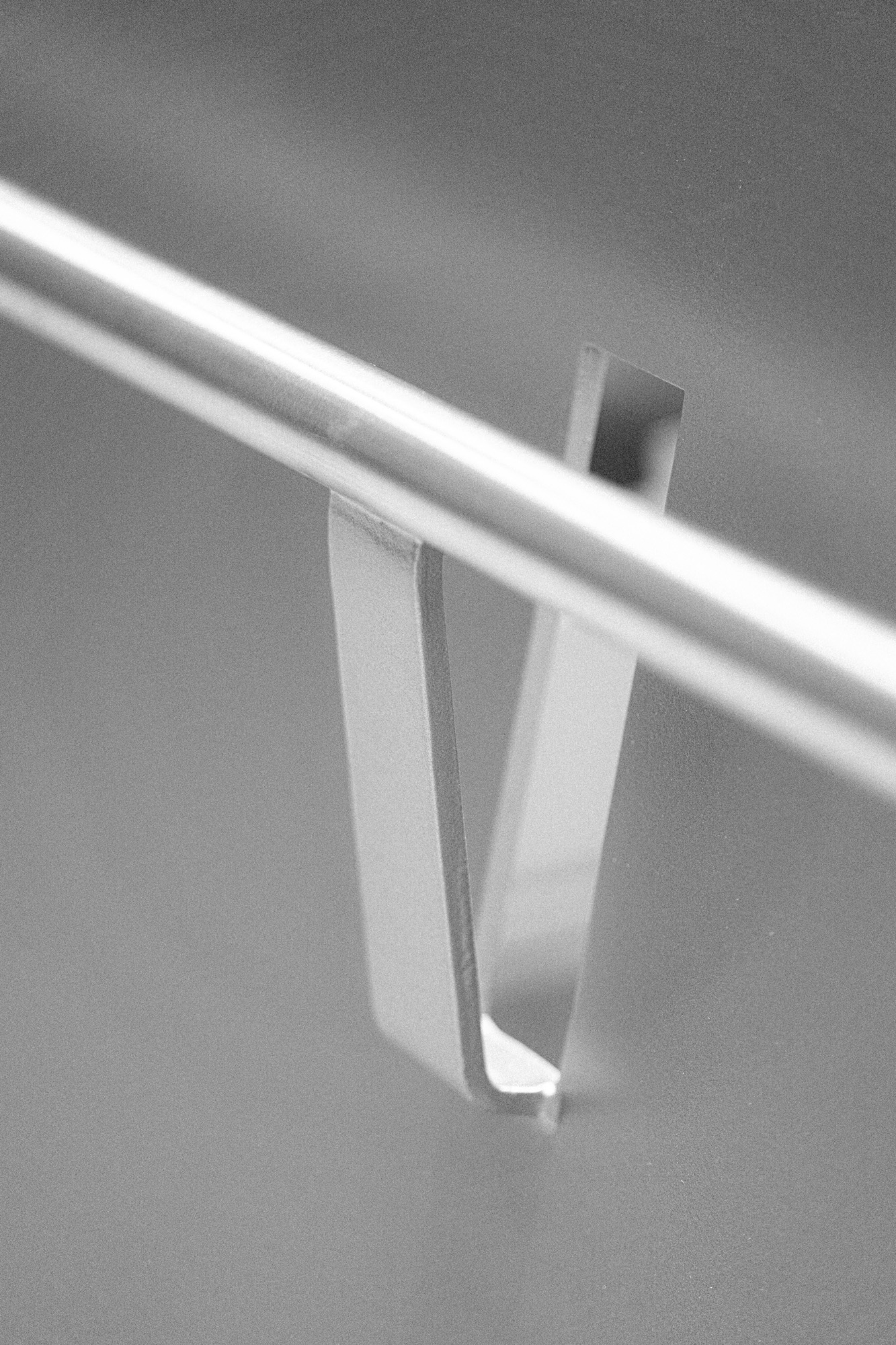

Central to this is the fact that nearly everything is placed within a continuous shelving-grid ‘cloud’, exposed and open for all to see. There are no hard barriers here, such as glass walls or display boxes, beyond a few discreet and intuitive design gestures – for instance, a ‘moat’ gently delineates areas with more delicate items and elsewhere, sensitive materials, such as textiles, are stored in dust- and light-proof sealed drawers or cabinets. Once inside, visitors are immersed in V&A history as objects of all scales, mesmerisingly and seemingly floating, appear in all directions, seen through glass flooring or peeking from behind each other. A new service, the ‘Order an Object’ experience, means anyone can book to see any object they like on-site. It is radical as it is satisfying.

‘As museums continue to collect objects faster than they can build more exhibition space, storage inevitably occupies a larger and larger percentage of a museum’s footprint. It’s therefore imperative for storage to contribute more to the public,’ Allin says. ‘In addition to preserving objects, museum storage can reveal the dynamics and complexity of museum operations. New acquisitions, conservation decisions, loans, categorisation and sorting systems, and deaccessions – these all speak to the making and remaking of culture alongside public exhibitions. By exposing these otherwise hidden objects, systems, and activities to the public, the idea of exhibition and display is significantly broadened. No longer relegated to a backstage structure that supports the exhibition spaces of the museum, the V&A Storehouse will be a new kind of museum in its own right.’

The design’s unconventional nature is not unexpected in the DS+R universe. The New York-based firm has been behind pioneering projects that have defined their respective typologies since its inception in 1981. With projects such as the High Line in New York and The Broad in Los Angeles under its belt and openings that challenge the norm, such as this V&A one, coming up, the studio is the subject of a long overdue, comprehensive monograph published by Phaidon this year and available now; Architecture, Not Architecture: Diller Scofidio + Renfro, celebrates the nearly 45 years of the studio’s existence – a moment, that made the recent loss of one of its original founders Ricardo Scofidio, life and work partner to Liz Diller, the other founder (Charles Renfro and Benjamin Gilmartin are also now partners), all the more felt in the industry.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Back in East London, as a working storage and conservation facility, the Storehouse is fully hybrid, mixing its revolutionary public access with specialist workshops, creative studios and education spaces. The main, dual-identity display and storage areas unfold through the fairly agnostic architectural vehicle of its one-size-fits-all, utilitarian and hardwearing steel shelving systeml. Shrouded objects sit next to exposed ones in a way that is neither particularly polished nor precious, placed behind glass or hidden away. There is barely any staging or theatre either. This is a pragmatic look into the daily, real life of V&A’s Wunderkammer of a collection. Off this main area, sections such as the Clothworkers Centre (where monumental tapestries, textiles and theatre stage cloths are shown in rotation) and rooms for careful upkeep are either fully accessible or visible through glass, where the public can see the conservators in action.

Ultimately, V&A Storehouse is a delicate balance between agency and protection – the desire to show off a large family of precious objects and the need to keep them safe.

Allin explains the project’s biggest challenge lay precisely in this push and pull: ‘Conservators prefer dark spaces with as few visitors as possible; curators need audiences and light to show off the objects.

‘These competing agendas led to a whole range of technical issues that had to be solved, involving air circulation, lighting, touch distance, and so on. As soon as you bring the public in, you’re compromising storage.’

And the V&A is planning for considerable footfall. Reeve hopes this newcomer will resonate with a variety of audiences – ‘No other institution is enabling access to national collections on this scale,’ he highlights – making this an exciting addition to the capital’s cultural scene and a valuable and compelling resource for East London.

This article appears in the June 2025 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print on newsstands from 8 May 2025, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).