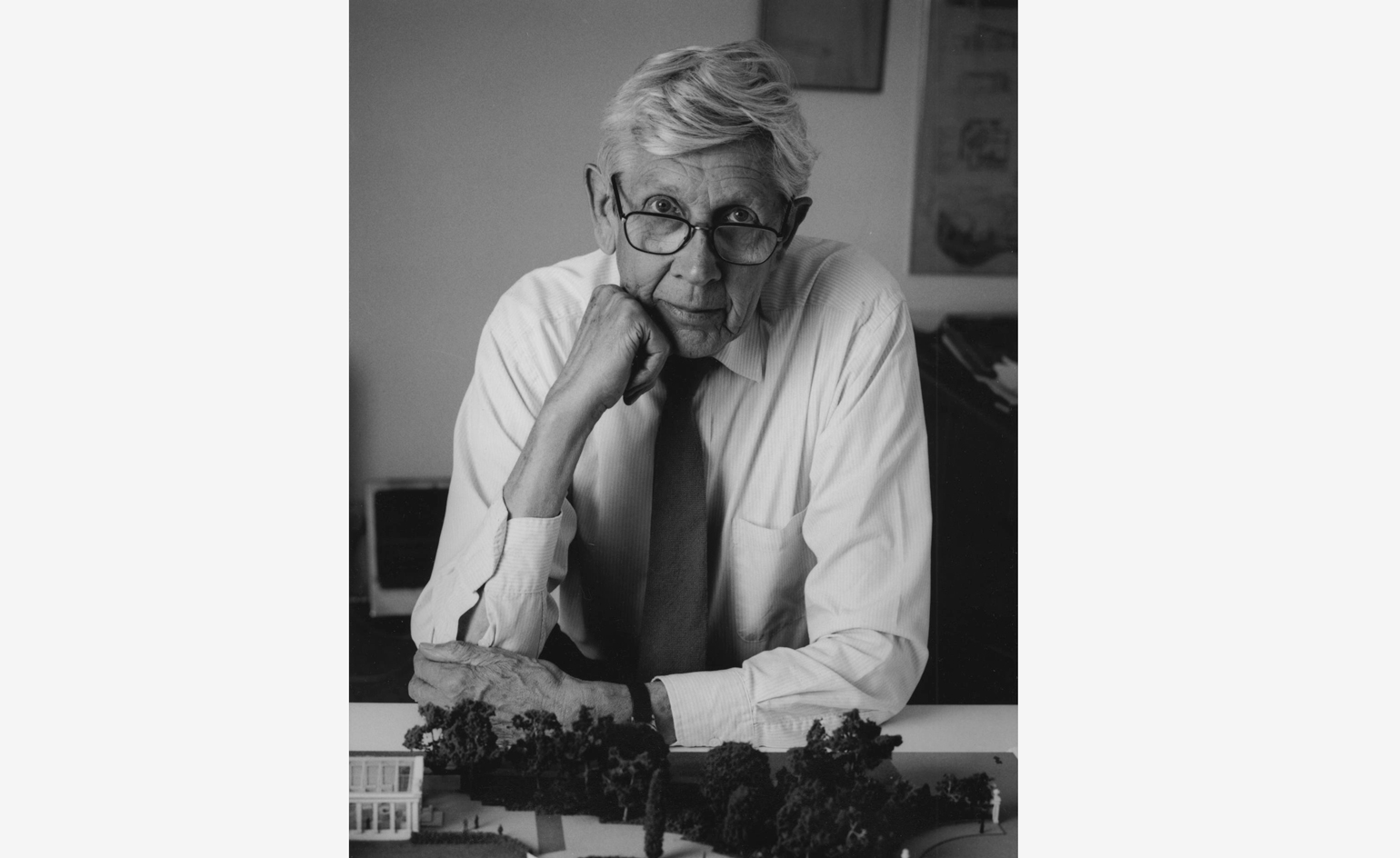

A tribute to architect Trevor Dannatt (1920-2021)

British architect Trevor Dannatt OBE RA (1920-2021) was known for his thoughtful and sensitive designs, which wove humble, traditional materials and modernist ideas. For our May 2012 issue (W*158), his son, art critic Adrian Dannatt, gave an account of one of the architect's new projects at the time, a private house in Petersfield. Here, we republish it in tribute

David Spero

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

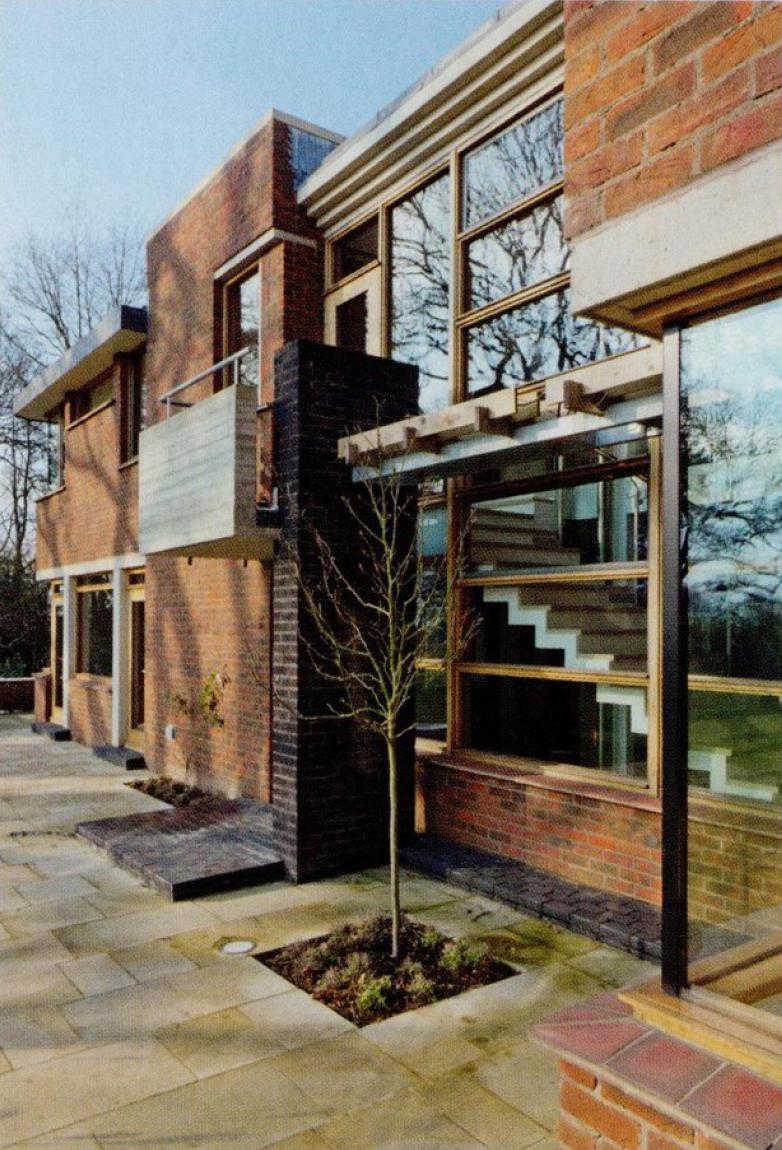

This is a house whose sole intention is to work perfectly for its owners, albeit while providing a certain satisfaction for its creator in the elegance of its solutions and innovations, a house to be lived in and to be relished by its guests, its satisfactions tactile and spatial as well as visual. This is a place designed by someone with a long working experience of such buildings. From the listed Laslett House in Cambridge, completed over 50 years ago, to the celebrated Pitcorthie House in Fife, built in 1968, Trevor Dannatt has developed a subtle, even humble, aesthetic of great sophistication, with every project recognisable as from the same hand. ‘I like a country house where you can look out of the window and see another part of the same building,' my father says, the simplest of statements yet one that acknowledges its own grandeur, its own import, and its own historical continuity, as true of Chatsworth as here.

While I am naturally proud to boast that my father is a 92-year-old practising architect, I am even prouder to reveal that this elegant brick-built house – surely among his best – is secretly thanks to myself. Or sort of, for having found the clients and persuaded them that my father would be the ideal architect for their new house, I handed them over and had nothing more to do with the project (apart from fielding the occasional, inevitable, complaint from either side). Thus the pleasing paradox of a project in which I had absolutely no involvement whatsoever, but which would not have existed without me.

Spread from the May 2012 issue of Wallpaper* (W*158), featuring the original piece by Adrian Dannatt

It didn't take much to convince the clients of the numerous advantages of my father's employ. There was only the possible disadvantage of his advanced age, but otherwise he was the obvious candidate. Indeed, there was even a sort of snob factor, dare one say novelty bonus, in employing an architect quite so venerable – for in today's culture, both the very young and very old are inherent stars.

My father knew modernist architects such as Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright and Alvar Aalto. He worked for Britain's then pre-eminent modernists Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry (turning up at their Bedford Square offices during the Blitz only to find a smoking hole), and to list all the celebrated designers and artists with whom he worked, or whose work he has collected, is a history of the 20th century in itself.

I grew up in the ultimate midcentury modern milieu – our early Victorian villa in Islington disproving the cliche that all modernist architects lived in Georgian houses – where the pots were by Lucie Rie, the fabrics designed by my mother for Heal's, the paintings by Patrick Heron, and the furniture by Finn Juhl, one of my father's closest friends and a regular visitor. Other visitors included engineer Ove Arup, who always carried chopsticks in his pinstripe suit, and Edgar Kaufmann Jr. A writer and art collector, Kaufmann was mostly celebrated for having persuaded his parents to employ Lloyd Wright as the architect for their weekend retreat, the result being America's most famous modern house, Fallingwater.

The Sussex house is an astonishing achievement, if not yet quite as iconic as Lloyd Wright's cantilevered classic. This is a building as grand, large, expensive and luxurious as any multimillionaire's new mansion, yet one which breaks all the rules as to how they are supposed to appear. In fact, one could confidently state that it is totally unique among private houses built in Britain in the last decade in its absolute refusal of any ostentation or any hint of vulgarity. It is a long academic essay, an extrapolation of the history of the country house and of modernism itself. And while the majority of new houses are also directly derived from International Modernism, they come from Le Corbusier and his Villa Savoye, or even Marcel Breuer's soi-disant Brutalism rather than the warmer Scandinavian humanism here evident, most obviously Aalto's Villa Mairea.

Most of these houses are designed for a ‘fuck you' effect, their look both defensive and aggressive, while this house merely whispers ‘come inside, walk around and see what you think'. Instead of being angled to serve as the perfect backdrop for a car commercial, this house is intended to inspire scholars to pen dissertations. From the sober brick walls and warm joinery, there is a refusal to grant the preposterous pretensions of the day; no panic room or walk-in fridge, no media lounge, gym or wine cellar. And instead of an initial elevation to deliver a first impression of high-cost drama, it has the subtlest, quietest of frontage, actually shielding, not promoting, its grandeur.

This is both a traditional country house, with its long corridor for boots and coats, and library, and a contemporary demonstration of the architect's essential art, that of circulation, the practical realities of where things need to be, and how we really want to live every day. The house is impressive in a radically different way from those whose primary intention is visual, to make a theatrical photograph. For here, instead of the reproducible image is the irreducible and irreplaceable physical sensation of living, walking and looking through these volumes, these plotted symmetries, axes and echoes.

But despite its success, and the content of my clients, I feel my work is not yet finished. Lloyd Wright was 91 when the Guggenheim Museum was completed, and Oscar Niemeyer is still designing cultural centres at 104, while my father, despite being a longtime art collector and patron (he designed the Whitechapel Gallery's exhibitions for both Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko), has yet to design any sort of museum or gallery, a lapsus that cries out for correction.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

- David SperoPhotography