Exclusive: Thom Yorke and artist Stanley Donwood reminisce on 30 years of Radiohead album art

As the pair’s back catalogue of album sleeves, paintings, musings and more goes on show at Oxford’s Ashmolean, Radiohead singer-songwriter Yorke and his longtime collaborator Donwood talk exclusively to Wallpaper’s Craig McLean

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

At Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum – amidst the sturm und drang of impending doom rendered on album sleeves, the swashing dollops of tempera and gouache paints liberally applied to Covid-era canvases, the black-spider scribbles in notebooks belonging to one of our greatest and most confounding lyricists – there’s a wonderfully deadpan piece of writing. It's part of an extended text under one of the giant, wall-hung images that characterise ‘This Is What You Get’, a capacious and colourful and brilliant new exhibition of the work of Radiohead’s Thom Yorke and his visual artist collaborator Stanley Donwood.

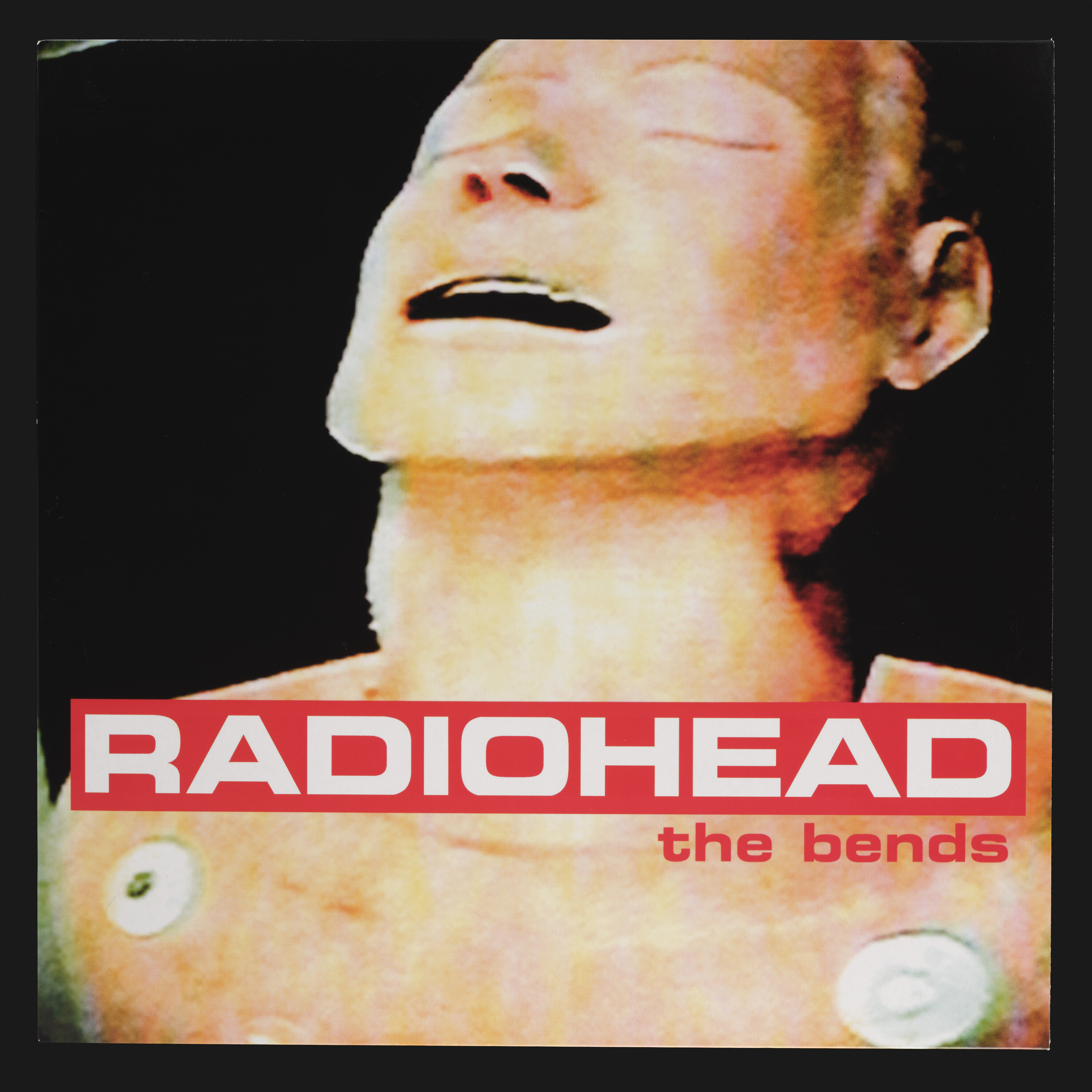

Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke, The Bends, 1995. Album cover

‘Donwood’s initial idea for the album cover,’ runs the caption beneath the pair’s sleeve artwork for Hail to the Thief (2003), ‘was to create enormous topiary phalluses, and digitally introduce them into the gardens owned by the National Trust, but Yorke was unconvinced.’

‘Hahahahah!’ says Yorke with a burst of laughter when I read that back to him. Why, one wonders, was he so unconvinced?

‘It was a brief conversation when Mr Donwood arrived in Los Angeles,’ the musician, 56, replies of the friend, real name Dan Rickwood, he met in the early 1990s during their time as art students at Exeter University, and with whom he makes all the visuals for Radiohead, for he and guitarist Jonny Greenwood’s other band The Smile, and for his solo projects. ‘He walked into the [recording] studio, sat down and started saying this. I had five minutes of panic.’

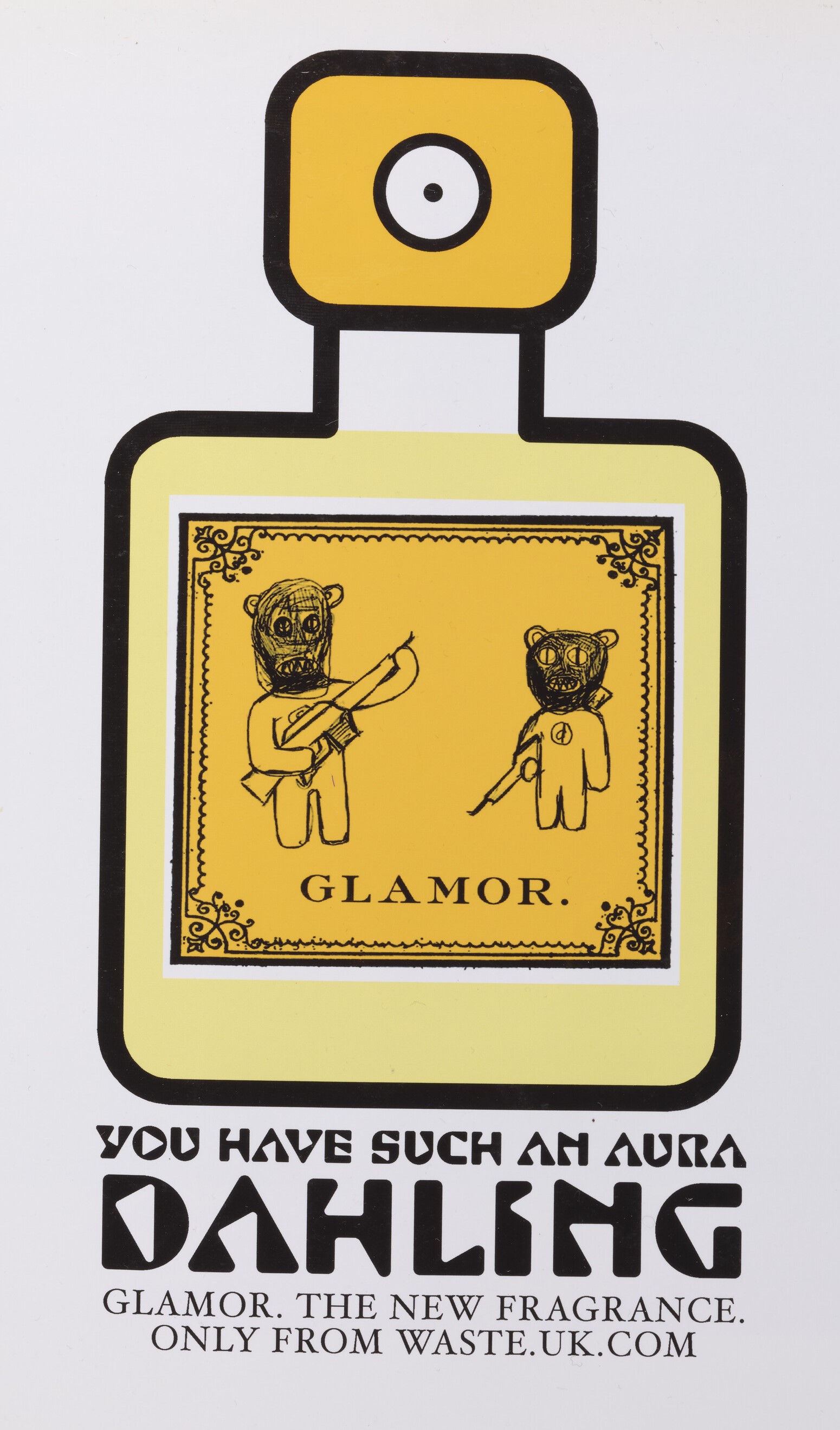

Thom Yorke and Stanley Donwood, Test Print – Glamour, 2000

‘Yeah, because we were supposed to build the artwork in two weeks,’ replies Donwood, three weeks younger than Yorke. ‘But I didn't know how to do this, how to make this happen. I had joined the National Trust, though.’

‘The first thing I said to you, even before I said, “I don't think this is going to work”, was something like: “Don't we need three or four years to grow it?”’

‘Well, it was all gonna be about chicken wire and astroturf,’ clarifies Donwood. ‘I was gonna cheat.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Yorke: ‘Oh, OK, ha ha!’

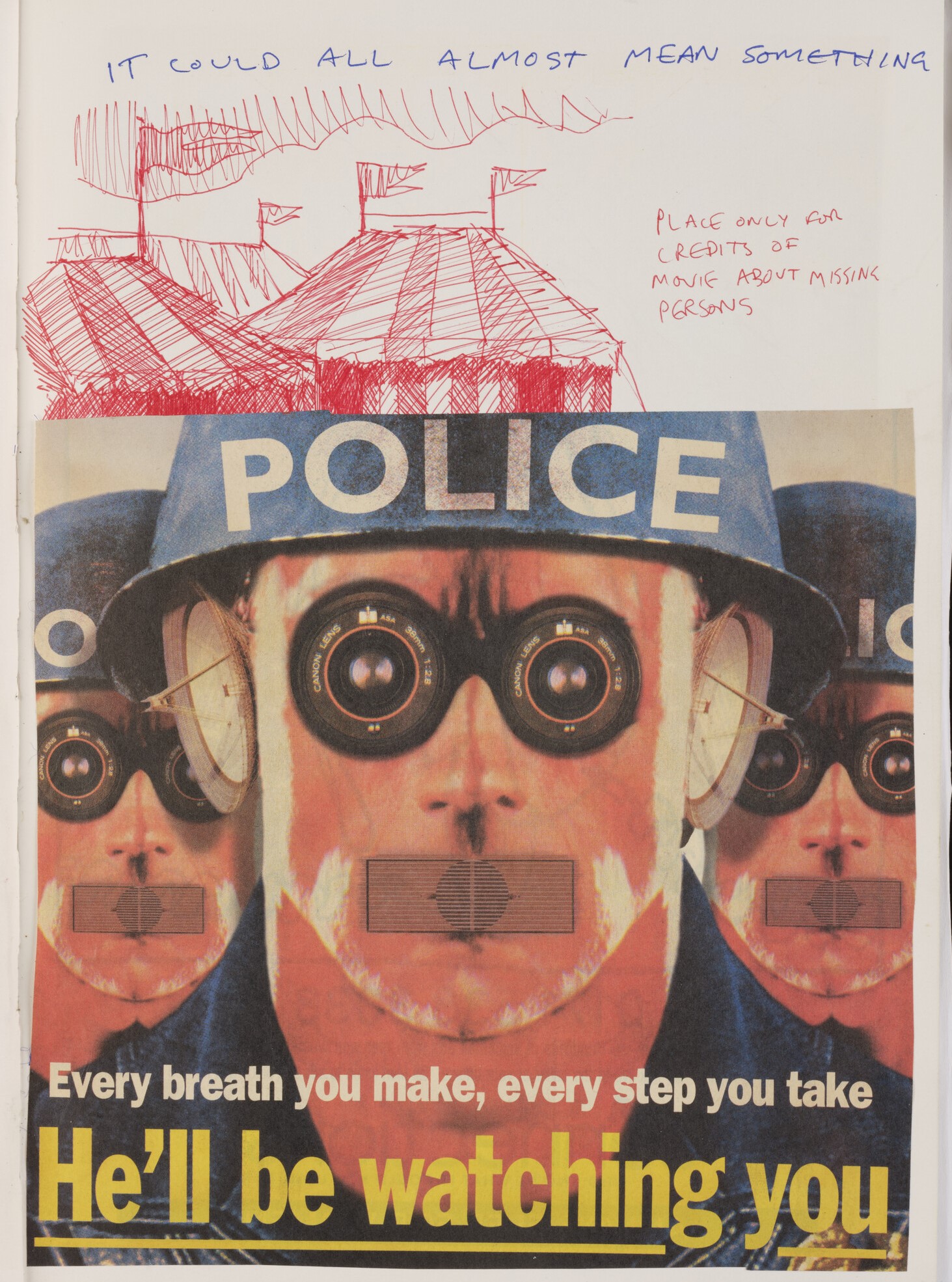

Thom Yorke and Stanley Donwood, page from a notebook, 1996-98

Thirty years into a creative partnership that began when they co-created the cover art for Radiohead’s 1995 album The Bends (they snuck into Oxford’s John Radcliffe hospital to photograph an iron lung but ended up snapping a resuscitation dummy), Yorke and Donwood are still making each other laugh. Still making each other think. Still making each other step out of their comfort zone. And that includes today, with the pair yielding to something on which they’re hardly super-keen: an interview. Separately? Not likely, mate. Together, exclusively for Wallpaper*? Oh, go on then…

An exclusive conversation with Radiohead’s Thom Yorke and Stanley Donwood

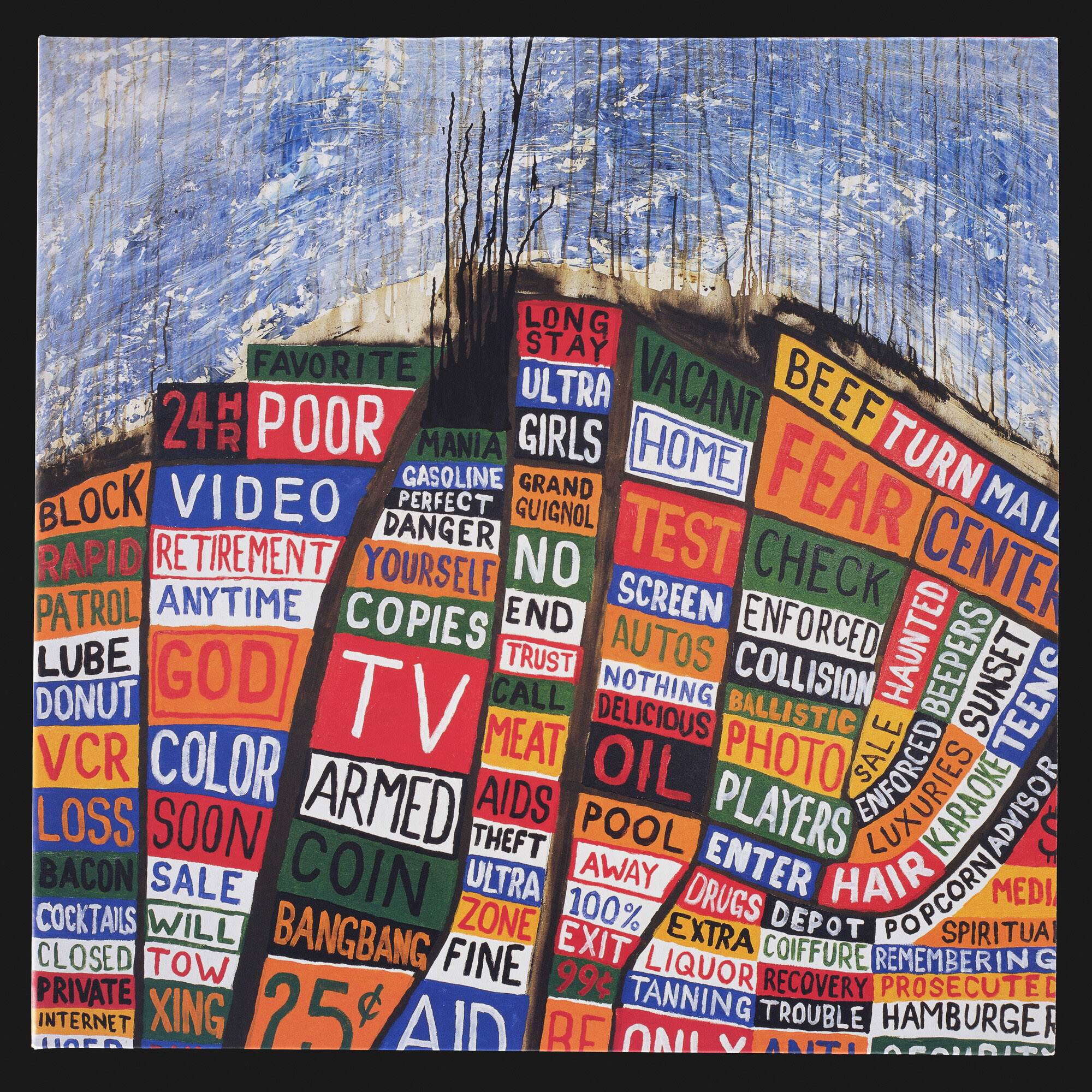

Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke, Pacific Coast, 2003

Wallpaper*: Thom, why submit to a five-month exhibition, in an august institution, that lifts the lid on one aspect of your creativity – and that has, as you've put it, ‘taken everything’ out of you?

Thom Yorke: Submit, ha ha. Submit being the word. Um... I think we were as curious as everybody else, really, about it… It was a slow-burning process from when we were going to do a Kid A installation [in 2020 for the album’s 20th anniversary]. Then that became a game…

Thom Yorke, notebook featuring lyrics for Karma Police, 1995

Stanley Donwood: …because of Coronavirus. We were talking to all these places, like the V&A and the Albert Hall. It was really interesting.

TY: It was really interesting coming up against the municipalities as well. Anyway, oomph, dodged that one. But then, as a practical idea, it was bananas anyway. But we'd done all these digital mock-ups, which we're kind of into. What that meant was we were forced to go and catalogue [that] period of our work. Go and find all the books. Go and find all the scraps of paper. Go find the files and all that sort of shit.

That very slowly morphed into kind of an exhibition... An installation became an exhibition became an archiving process. And the archiving process became kind of interesting, although I was always very worried. [I remember] PTA – [film director] Paul Thomas Anderson – saying to me: ‘Don't look backwards, it hurts.’ But at the same time, it was weirdly fascinating.

Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke, Untitled, 1997

W*: You've talked of the time around 1997’s OK Computer as ‘an odd time for me personally... of living in a bubble... touring endlessly... feeling like everything was moving too fast’. I see that reflected in the cover artwork, which is based partly around photographs you took of motorways and a highway interchange in Connecticut. In that very modern parlance, how triggering of those feelings is it to see those images now, in large scale, in the Ashmolean?

TY: I wouldn't say it's triggering, because, in fact, it was quite cathartic. When we finished [the OK Computer artwork], I felt it was a quite good full stop over that period. It's like: that's what it was like. Even though it's sort of nonsense, for some reason it said what we needed to say.

SD: There was a description of [that] artwork in a newspaper. Something like: ‘It almost looks like it means something’. Which I thought was fucking brilliant. Faint praise!

TY: Ha ha, damned with frame praise. As usual.

‘We had these huge canvases, and it was this idea of making huge, gestural marks. But I was always conscious that [the work] was going to be reproduced at 12 centimetres square on a CD cover’

Stanley Donwood

Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke, Get Out Before Saturday, 2000

W*: Dan, for Kid A, you brought in huge, six-feet-square canvases and used Artex and palette knives. In what way was that a response to – or even a pre-figuring of – the music that Thom and the band were making – with, infamously, no little difficulty – for that album?

SD: I don't know. We rented a little art studio in a freezing cold warehouse. We had these huge canvases, and it was this idea of making huge, gestural marks. But I was always conscious that [the work] was going to be reproduced at 12 centimetres square on a CD cover. So you couldn't obviously pack a lot in there. And the music was happening at the same time. Then we moved the studio to where the band were working.

TY: It was a really, really long process. And there was lots of different flailing around. Same with the recordings. And generating a lot of things that made absolutely no sense at all. Until you start looking back at it. There was this part where Dan was moving these canvases into the main studio and hanging them if they were unfinished. That was a real [lightbulb] point. That coincided with us finally getting the beginnings of certain songs and arrangements. But, you know, that was months and months and months.

Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke, The King Of Limbs, 2011

W*: In contrast, the initial impetus behind the next-but-one album, Hail to the Thief (2003), was to make it really quickly – two weeks in Los Angeles was the initial idea. You've said, Thom: ‘I was writing stuff that I wouldn't normally write lyrically because I didn't really have time to think about it.’ Once you got past Dan’s topiary knobs, were there parallels with the artwork that was eventually created?

SD: I was very unfamiliar with Los Angeles. It shouldn't really be there, because the climate and the landscape are quite difficult for humanity. And we went there, we went to this hotel – and we're in a desert, basically – and you go for a piss, and there's huge urinals filled with ice. Frozen water! In a desert! It felt like an incredibly decadent environment.

London Views (6 of 14), 2005-6

And there's a lot of plastic. A lot of products from oil everywhere. All of the colours that we used in the paints are coal tar dyes and artificial colours – chemically made colours. And everywhere there are so many words, on all of the adverts. Even little signs on lawns that say ‘armed response’. You're like, fucking hell, for what, walking on the grass? It's very heavy.

So I was writing all this stuff down, and the first couple of paintings were just completely covered in all these words, ripped down while going through the city.

Thom Yorke and Stanley Donwood, OK Computer, 1997

Stanley Donwood, Meteor Oligarchy, 2007

W*: To digress to the terrific new Hail to the Thief live album: Thom, you went back into Radiohead’s archives as you worked on the Royal Shakespeare Company’s recent Hamlet/Hail to the Thief piece. What were you looking for, and what did you find?

TY: Obviously it's a weird thing anyway, to try and find other people to play the band's songs. But there was something about listening to the live recordings that made whatever that song was a little bit more fluid. A little less fixed. A little less ‘no, it must be exactly like this’ or ‘the sound must be exactly like on the record’. All that stuff.

Thom Yorke and Stanley Donwood, poster

Because when we do our live shows, it's rough and ready. We don't spend – we didn't spend – a lot of time. It was just [a case of] whatever we had, we'd use. A DIY sort of mentality of playing the songs live. Which, you know, works.

So there was a certain energy that I needed to find. Because one of the things that was coming up while we were prepping the Hamlet thing was trying to find frenetic energy. Something that was vaguely troubling in the way the music would be played. And weirdly, I found that the live performances that I got sent from the archive had way more of that than the record. They seemed to suit this quite wrought state of mind, where there's a sort of simmering anger – but it's misdirected and it's confused and it's lost. It's hard to pin down, but it had more of the right sort of energy. It was then really inspiring, because I could go to this new set of musicians and say: ‘Listen, it's not about the particulars of this. It's about this.’ It was just quite eye-opening.

Thom Yorke and Stanley Donwood, OK Computer, 1997

W*: In the 30 years since you co-created the visuals for The Bends, album artwork has shrunk and shrivelled even further from the gaze. Now we don't even hold it in little plastic cases. We might see it just as a postage stamp illustration on our preferred streaming platform as we listen to this or that record. How is that diminishing impacting your views on how you make the art to accompany the music?

SD: We've always had this idea that, if you can see it across the record shop as a 12-inch-size picture, you're only seeing it as a little fingernail. And you go towards that if you're attracted by it. So we've always tried to make something that looks interesting enough to go towards – and then hopefully pick up.

‘The streaming thing… the fact that you just get a thumbnail of the image, it seems to be designed to make you not give a fuck. Which is a shame’

Thom Yorke

Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke, Wall of Eyes, 2023

TY: Also, the streaming thing in this context, it's more like the radio. The experience of using it is more like a radio in the background, rather than you really having a strong connection with what you're listening to. As you say, the fact that you just get a thumbnail of the image, it seems to be designed to make you not give a fuck.

Which is a shame. It gives you that sense of an endless stream of material which is all equitable. The same. Which is not the experience you would have got in a record shop. Or not the experience when you go around to your mate's house and they play you some obscure jazz record from the 1970s. That's not what that is. It's useful, but it's like an interim experience.

Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke, Soken Fen, 2013

‘I guess what's important is the question of whether it matters, the visual element for an artist that goes along with their music’

Thom Yorke

W*: That said, as we all know, vinyl is making a (pricey) comeback...

TY: I just constantly feel like there's another experience coming around the corner. I don't feel like this is it, you know? Obviously, yeah, the revival of vinyl sales helps a lot. But I guess what's important is the question of whether it matters, the visual element for an artist that goes along with their music. [Are we] freaks at the end of the cycle, or in the middle of another cycle that we don't understand? It's the same making videos, where you expend a lot of time and effort making one, and then they're like: ‘OK, so can we have the 15-second cut down for TikTok?’ And you're like: ‘Er...!’

It's all the same kind of things where [you think]: should I get upset about this? Or should I just carry on? I think I'll just carry on. Because, in a way, there's a compulsion to make this work. And there's a compulsion to see the two hitting, banging against each other. And it's really important to us. So that's all we know, really.

Thom Yorke and Stanley Donwood, Heavy Snowfall on House, 1995

W*: What might the art for the next Radiohead album look like?

TY: [mirthless but playful] Ha ha ha ha ha. Moving on!

W*: I know you're getting back into the painting studio this autumn. It would be remiss of me not to ask when Radiohead are getting back in the recording studio.

TY: I have no idea. Not on the cards from where I'm sitting.

SD: [In terms of the art] I've got a few ideas that actually never made it very far. Did I mention about how I joined the National Trust...? [The topiary] is still there, still got it…

TY: We've got lumps of it out back!

'This is what you get' is on display at Ashmolean until 11 January 2026, ashmolean.org

London-based Scot, the writer Craig McLean is consultant editor at The Face and contributes to The Daily Telegraph, Esquire, The Observer Magazine and the London Evening Standard, among other titles. He was ghostwriter for Phil Collins' bestselling memoir Not Dead Yet.