How Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners built The Macallan’s Speyside distillery

Look back at the journey behind the creation of the award-winning The Macallan Distillery in Scotland’s Speyside, by renowned architecture studio Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

Joas Souza - Photography

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Back in the summer of 2012 The Macallan – makers of luxury single malt scotch whisky since 1824 – launched an international competition for the design of a new and architecturally audacious project. Incorporating a new factory, HQ and ‘Distillery Experience' for visitors, the proposed building was to be situated on an existing field within 485 acres of The Macallan Estate and the listed Jacobean manor, Easter Elchies House, aka The Macallan’s spiritual home.

The client set architects and engineers a rigorous brief for a design-focused brand home that would project the vision and direction of the leading single malt whisky marque into the future. With the barley field site of the new building at the edge of Scottish countryside designated as an ‘Area of Great Landscape Value’ – a land corridor following the sweep and contours of the River Spey integral to The Macallan Estate and The Macallan Fishing Beat – any competitive proposal would have to be brave, bold and audacious while remaining sensitive to the surrounding environment of ancient Scottish earthworks, long cairns, brochs and wells. The importance of the neighbouring ancestral house had to be respectfully acknowledged but the new distillery would also be required to increase The Macallan’s production of whisky by up to a third. Quite a challenge.

Enter Graham Stirk of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, the London-based practice whose impressive portfolio includes One Hyde Park, the Leadenhall Building, NEO Bankside London and the Millennium Dome. Stirk provided a plan that mitigated the impact of the building; a response to the landscape as the primary context rather than the disparate nature of the existing built facilities and storage units.

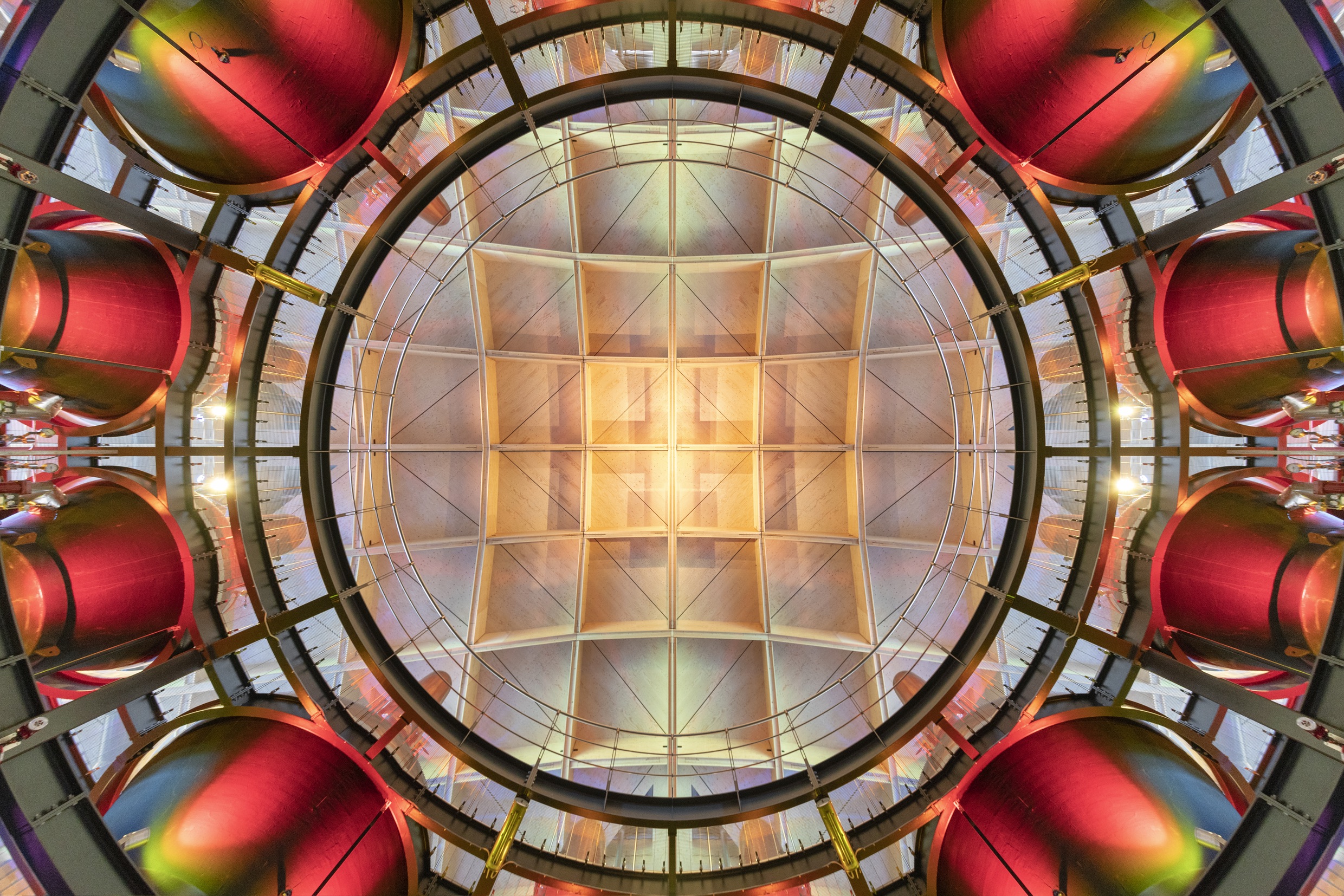

But it was Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners’ projected roof design that offered the most compelling prospect. Said to be one of the most complicated timber structures in the world – 1,800 single beams, 2,500 different roof elements, and 380,000 individual components, almost none of them the same – the undulating canopy would be a beautiful, meticulously engineered, wood and steel wonder.

‘Whilst the roof design is described as a landscape response, the roof was never intended to disappear or be lost within the hillside,' explains Toby Jeavons, Associate Partner and Project Architect at Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners. ‘As such, the roof is positioned on top of the retaining structure and not bound by it. This allows the upstanding depth of the roof structure to act as a balustrade to the grid line and to the Northern edge of the roof as it appears to meet the ground. As the roof "sails" above the retaining structures, it is freed from restraining ground pressures and loads.'

Eventually completed back in 2018, the roof structure consists of two principal parts, the primary tubular steel support frame and the rolling domes and valleys of the timber grid shell. The primary steel frame is laced through the centre of the timber beam structure and helps to resist the torsional forces. The timber domes act in compression and the interconnecting valleys are hung between the domes. All the roof beams are straight and all the cassettes are flat, double-skinned panels.

‘This provides the facetted appearance so important for the "engineered landscape",' says Jeavons. ‘Despite the highly repetitive and rotational roof geometry, the finished structure is constructed from over 380,000 components. All of the timber beams are vertical and a constant expressed depth of 750mm which allows for considered and neat interfaces with internal partitions as well as the solid and glazed facades.'

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The changeable highland weather and uncompromising Scottish elements also proved a significant factor in the building’s material construction and profile. ‘The architectural concept of the distillery allows it to thrive in the Scottish elements by reflecting the very nature that surrounds it. The profile is low and hugs the ground. The roof structure anticipates severe snow loading, and the natural green roof coverings utilise a specific, low maintenance mix of Scottish wildflowers and meadow grasses suited to the location.'

To satisfy the proprietor’s desire for increased yield, practicality and an efficiently attractive, visitor-friendly space, the architects envisaged a facility that contained a rhythm of production ‘cells' which could be conceptually added or taken away to provide the required capacity.

‘A production cell is a combination of the required fermentation and distillation vessels which we have positioned in a circular arrangement. This is to increase the visibility of the beautiful production equipment. By situating the hand-made copper pot stills in an elevated central position the building celebrates the entire production sequence.'

‘The distinctive roof configuration is a reflection of the circular production cells beneath it and takes the form of a laminated veneered lumbar (LVL) orthogonal grid shell. The use of timber is in part a reflection of the particular importance that The Macallan place on wood during its whisky’s maturation process – a crucial factor which accounts for up to 80 per cent of the character of the single malt whisky. The roof undulates with equal rhythm over four process cells below and is then pulled higher to the South where the roof accentuates and highlights the Visitor Experience’s point of entry.'

For inspiration, Graham Stirk and his team examined historic plans for the original estate dating back to the early 18th century, notably a Thomas Whyte plan, which hangs in The Oak Hall in Easter Elchies House. This helped inform the setting of the building, in particular, the serpentine approach to the Visitor Experience entrance at the southern end of the facility.

‘It was always important to us that the two buildings were physically joined,' says Toby Jeavons. ‘The Experience is the reception – and not a separate area where one learns about the distilling process abstractly. It was important to deliver a clear view into beautifully co-ordinated production area. In this building, nothing is to be hidden away.'

INFORMATION

Simon Mills is a journalist, writer, editor, author and brand consultant who has worked with magazines, newspapers and contract publishing for more than 25 years. He is the Bespoke editor at Wallpaper* magazine.