Inside a creative couple's magical, circular Indian home, 'like a fruit'

We paid a visit to architect Sandeep Virmani and social activist Sushma Iyengar at their circular home in Bhuj, India; architect, writer and photographer Nipun Prabhakar tells the story

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The first time I went to Sandeep Virmani and Sushma Iyengar’s house was in 2015, as an intern at the sustainability non-profit Hunnarshala Foundation in Bhuj, still trying to work out what architecture even meant when it wasn’t wrapped in glass and clad in aluminium sheets. Bhuj itself felt like a threshold: a desert town between the Rann and the Gulf of Kutch, ringed by Bhujia hill with its fort and snake legends, stitched together by craft villages and post-earthquake reconstruction stories.

Someone at the office said, almost casually: 'Come in the evening, we’ll go to Sandeep bhai’s place.' I didn’t know then that this was going to be the house I would keep returning to for the next decade – to share good news, to ask for difficult advice, to sit quietly when I didn’t know what to do with my life.

Explore the house of Sandeep Virmani and Sushma Iyengar in Bhuj

Sushma and Sandeep's house (Sushma ben and Sandeep bhai, as everyone calls them) does not announce itself. In a society rapidly filling up with glossy, compound-walled homes and sliding gates, it sits low and almost shy. There is no big gate, no grand driveway. You arrive in a small mud court, slightly uneven with Kolams and rangoli on the floor. From here, the first thing you see is the kitchen window.

That window became my weather report for the evening. If the oven was on and Sushma or Sandeep were moving around inside, it usually meant a nice hot cake would be served. She insists both of them are against too much machinery – no microwave, no washing machine, minimal appliances – but the oven is fully accepted as a co-conspirator in feeding people. More than once, I arrived to find a cake cooling on the counter, vegetables chopped for dinner, and the house already smelling like it was expecting guests. It always has guests.

On the other side of the house, a very different domestic drama plays out. There’s a small A-frame shelter on a sand patch: Assistant’s house. Assistant is a street dog Sandeep looks after, named as the sidekick to a bigger dog called Fuddu. This is a home that quietly extends itself to others – dogs, cats, birds, whoever passes through.

A circle in a cow’s mouth

Sushma and Sandeep told me, laughing, that they bought the plot no one wanted. It is what in local parlance is called a Gaumukh plot - wide at the front, narrow at the back, like a cow’s face. The frontage stretches generously along the street, then tapers into a tight corner. Traditionally, people avoid such plots. They’re awkward to plan, perceived as inauspicious, and structurally tricky. Which is exactly why this one was slightly cheaper, and exactly why they wanted it.

Behind the site lies a common plot of the neighbouring colony, left unbuilt for years. On two sides, other plots were bought but never developed. At one point, for almost 15 years, their house had emptiness on all four sides. 'We chose it, because we knew we would have openness,' Sushma said. Even now, with one big neighbour finally built, three sides remain open enough for wind, light and gossip to move freely.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

We chose it, because we knew we would have openness

Sushma Iyengar

Faced with this odd, tapering plot, Sandeep drew a circle. 'I thought a circle would work well,' he told me. 'In this awkward shape, it allows the spaces to flow easily.' The circle pulled the structure inward, freeing the edges to negotiate the strange boundary lines. As a student, he had once designed a dancer’s circular house. 'That was the only organic design I had done,' he remembers. It never got built. Years later, after working with Pritzker award-winning modernist architecture master Balkrishna Doshi, with Laurie Baker (India's Gandhian architect), and for years with craftsmen across Kutch, this modest circle finally gave that early instinct a home.

The plan starts with a courtyard. 'First we made the courtyard,' Sandeep says, 'and then we made rooms around it.' Two main bedrooms and a guest room are strung along the arc, with the kitchen facing the street. That last bit is non-negotiable: 'We spend most of our time in the kitchen,' he says. 'You should be able to see who is coming and going.'

Air, fruit and small mistakes

When Sandeep talks about the house, he keeps circling back to the climate. 'I wanted to design a house where there is no need for an air conditioner,' he says simply. The idea was straightforward: use orientation, materials, trees and openings in such a way that the house cools and heats itself as far as possible.

Kutch is a place of extremes: blazing days, cooler nights, strong winds. The veranda, where most of life in this house happens, is oriented roughly south–west, aligned with the prevailing winds. Sandeep planted trees in front of it so that their shade falls on the walls and roof while still allowing wind to slip underneath. The two main rooms face east and west, reducing direct solar exposure on their longer faces. Small windows on the south, big windows on the north.

Social activist Sushma Iyengar, conducting a guided tour of the exhibition 'Living Lightly' at the Mill Owners Association building in Ahmedabad

Between the veranda and the inner courtyard, the house forms what Sandeep describes as a Venturi [the Venturi effect presents when air or fluid speeds up through a narrow, constricted vessel section]. Because the two-bedroom walls are wider outside and slightly pinched where they meet the veranda, air speeds up as it passes through. On hot evenings, when everyone gathers there, you can feel the wind accelerate, wrap itself around people, cats, conversations, and plates of food.

Has it all worked perfectly? No, and they are the first to point this out. 'In our room, it stays nice,' Sandeep admits. 'In the other room, not so much.' In that second bedroom, he placed the bathroom on the windward side. The breeze that should have cooled the room now mostly cools the bathroom. 'The bathroom should have been on the other side,' he shrugs.

He is more satisfied with the overall metaphor. 'The idea was also that it’s like a fruit,' he told me. 'From the outside, it is hard, black. From the inside, it is soft and red.' The outside walls are dark, built in rough stone and plaster, the roofline low. Inside, the floors are white terrazzo, the walls lime-washed, the courtyard glowing.

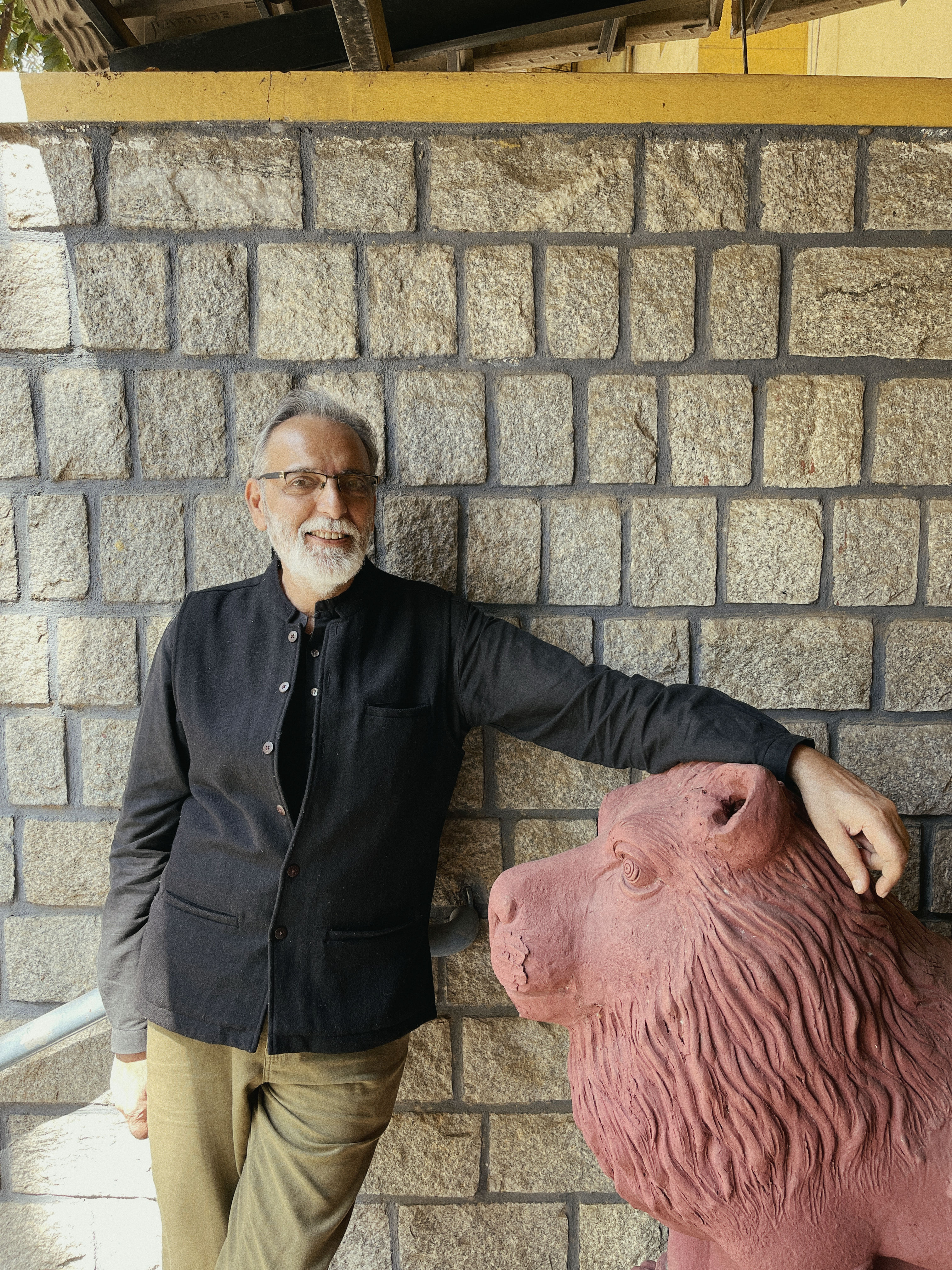

Architect Sandeer Virmani, at IGNCA in Bangalore

Materials here are less about style and more about relationships. The structure is a layering of modest experiments: an early thatch roof that had to be replaced with tiles after Diwali fireworks repeatedly threatened to set it on fire; a thin ferrocement layer on wooden ‘lost shuttering’; small steel trusses hugging the outside of the circle so they don’t visually clutter the inside. A local potter made earthen pots for filler slabs after Sandeep and Sushma brainstormed with Jinan, a potter from Kerala who briefly worked with them in Bhuj, exploring how Kutch crafts could enter architecture.

The house was under construction during the devastating 2001 earthquake in Bhuj. The front veranda, then an added-on element whose beams hadn’t yet been tied in, collapsed. Inside, the central veranda shook so violently that afterwards they decided to add slender columns, not to carry a load but to hold the roof in place in the next big tremor. The house remembers the quake in its bones, but it also remembers the slow rebuilding of Bhuj around it - its residents were at the forefront during the post-earthquake rehabilitation.

Sushma’s no-wall dream

If the circle started with Sandeep’s sketch, the openness inside belongs very much to Sushma. 'I have always liked round houses,' she told me. 'And the one thing I just don’t like is walls.' Long before she moved to Kutch and worked with women’s organisations and craft communities across the region, she dreamt of a round, wall-less home. When she and Sandeep discovered that they both secretly liked round houses, the decision took care of itself.

The resulting plan is almost radically open. Their bedroom, kitchen and the living space form a single flowing space. Only the guest room is fully enclosed, and even that opens directly onto the shared veranda, not onto some closed corridor.

'I remember we had a lot of discussions on walls,' Sushma said. Sandeep and their friend Kiran Waghela eventually convinced her to accept one partial wall, a small curved screen between their bathroom door and the rest of the room, just enough to give privacy when stepping out of the bath. 'That was the only wall,' she laughs. 'And even that we made only half.'

For a while, when Sandeep’s mother was unwell, her full-time caregiver lived with them. They added a small room at the back for him. Then the daily navigation of privacy was real: whoever came to the kitchen inevitably crossed visual lines with the bedroom.

And yet, the same layout that complicates privacy also produces one of the most generous gestures in the house: the way the veranda sits between their bedroom and the guest room. 'This thing I would repeat anywhere,' Sushma says. 'To have the room opposite and the veranda in between.' A guest wakes up, steps straight into the veranda, and has immediate access to the sky, plants, chairs, and people. You’re not trapped in your room waiting for the household to wake up, nor are you forced into the kitchen the moment you step out. You can sit alone with a book or join whoever’s there.

'It gives a lot of freedom,' she says. 'For a guest, it’s like you are almost living in your own space. For us, it gives distance and intimacy, both.'

Gandhi Ashram chairs and circular drawers

For two people who wanted minimal furniture, their house has accumulated a surprising amount of it – almost all with stories.

'We were totally against furniture,' Sushma says. Early on, they solved seating simply by turning the architecture itself into furniture. Stone slabs run along curved walls, forming continuous seats by the bay window, in the living room, even outside. Then her mother came to stay. By then already elderly, she found the stone benches too hard, too low. 'She said, "You have turned this place into Gandhi Ashram”,' Sushma recalls her indicating the modesty of the house. 'Bring some proper chairs, then I will come back.'

Years later, after both her parents and Sandeep’s mother passed away, the couple inherited two armchairs from her family home – their parents’ first big purchase after marriage. Those chairs now sit in the veranda, seventy-five years old and still firm, the designated thrones for ageing knees.

Curved walls demand curved solutions. A carpenter from Ahmedabad built a semicircular dining table that tucks perfectly into the bay window niche, flat on one side and rounded on the other. In the kitchen, opposite the stove, a marble-topped platform floats on tapered wooden legs, its drawers following the arc of the wall. Even outside the bathroom, the storage unit is subtly curved, the carpenter having figured out how to bend function around geometry.

They also made an early political choice about storage: as few cupboards as possible. 'The more cupboards you keep, the more stuff will accumulate,' Sushma says. They have one cupboard in their bedroom, shared between them, and one larger cupboard in the guest room.

Books, inevitably, broke this rule. Initially stored in two Russian kitchen cabinets that Sandeep’s mother had brought back decades ago, they kept multiplying. During COVID, they finally gave in and turned an entire stretch into a work table with a book wall above. It’s one of the few places in the house where a modern, city-like density of objects appears.

In the washing area outside, instead of the typical low Indian washing platform where you squat or bend awkwardly, they built a tall, gently sloping basin inspired by Sushma’s uncle’s house in Bangalore. He had designed it for ageing bodies that could no longer sit on haunches. They copied it almost exactly. For a home without a washing machine, this one move has probably saved hundreds of aching backs over the years.

Wire mesh, and the long view

Not everything here is soft and crafted. Some details are brutally pragmatic. The window grills, for example. If you look closely, they are not delicately designed bars but simple weld mesh sheets, the kind you might use to fence a construction site. 'Really horrible,' Sushma calls them, half-joking, 'but they have lasted 25 years.'

The story behind them is less funny. When the couple finally shifted into the house, much work was still unfinished. No grills, some windows missing, the surroundings empty. Then Sushma’s father passed away, just five days after they moved in. She rushed away; Sandeep followed soon after. Before catching his flight, worried about leaving his mother alone in an exposed house in a half-built colony, he grabbed the quickest solution he could find: weld mesh on every opening. The 'temporary' fix never got replaced.

It’s easy to imagine this house in any architecture magazine as 'a circular eco-home in Kutch.' But for me, it has always been less about its photogenic moments and more about its long, patient relationships: with wind, with neighbours, with non-human visitors, with grief.

Sandeep, who has spent decades working with communities to rebuild and reimagine habitats after disasters, often talks in public lectures about 'humanising architecture,' shifting the focus from objects to processes, from monuments to everyday lives. Sushma’s life’s work with rural women’s collectives, craftspeople and pastoralists has been about similar questions of dignity, access and agency.

This house sits at the intersection of those two trajectories. It is not a showcase project; they never put it into lectures for years because it felt too private. Locals from the colony come, admire it, call it 'beautiful,' then go away and build straight-walled, boxy houses for themselves. 'They think this is a park,' Sandeep laughs.

One of the best circles I know

I have now visited many circular houses over the years, such as traditional Bhungas in Kutch, experimental eco-resorts, and dome homes. This house in Bhuj feels different. It’s gentler, more lived-in - and in its form, I still think it is one of the best examples of a circular plan I’ve experienced.

For me, it's a house I have arrived at in different moods, at different ages, carrying different questions. I’ve slept in the guest room across the veranda, woken early and crept out so as not to disturb anyone, only to find Sushma already making ginger tea and Sandeep feeding the cats in the courtyard.

If Jeanneret’s house in Chandigarh taught me about the quiet discipline of modernism, and the Kanade brothers’ house in Nagaj revealed the dignity of exposed stone and carefully honed proportion, this house in Bhuj has taught me something smaller and maybe harder: how architecture can be hospitable without being grand and experimental without being loud...

It’s easy to design a circle. It’s much harder to make one like this house. That’s the circle I keep going back to.

Nipun Prabhakar is a photographer, writer, and community architect working at the intersection of memory, migration, craft, and the built environment. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, etc, and he has collaborated with institutions such as MIT, Cornell, and IDS. In 2023, he was invited to present his work at the RIBA’s inaugural Architecture Photography Festival. He is also the founder of the Dhammada Collective.