The building that put Arthur Mamou-Mani on the map lasted just more than a week, before going up in flames. This would have been the kiss of death for any other architect. But for Mamou-Mani, it was a career-making moment: the building in question, called Galaxia, was the temple for the 2018 Burning Man festival in the Black Rock Desert in Nevada; and its fiery demise was not only intentional, but part of a long-held tradition. Despite its brief lifespan, Galaxia left a deep impression in the hearts of many, and propelled its creator to the forefront of digitally designed and fabricated architecture.

It was late 2017 when the London-based French architect was announced as the winner of the competition to create the following year’s Burning Man Temple – a non-denominational space at the heart of the annual countercultural arts event, destined to be burned at its close. He envisioned a spiralling tower evoking ‘stars, planets, black holes, the movement uniting us in the swirling galaxies of dreams’. It was formed of pre-cut timber, assembled on-site as triangles, and folded into 20 modules like a giant piece of origami. At its periphery, small alcoves allowed moments of quiet reflection. Its central space held a chandelier of 3D-printed giant teardrops, a reflection of the technologies on which Mamou-Mani established his practice.

Arthur Mamou-Mani and the Burning Man Temple

The plans were agreed and anticipation was rife. Then came the challenge of fundraising. Burning Man is based on ten principles set out by its co-founder Larry Harvey, one of which being radical self-reliance: encouraging participants to ‘discover, exercise and rely on their inner resources’. This meant figuring out how to survive and build a community in the desert, but also, in Mamou-Mani’s case, finding the construction budget to top up the modest $100k offered by the Burning Man organisation.

Mamou-Mani and his collaborators took to the crowdfunding platform Hatchfund, selling T-shirts, jewellery, and 3D-printed models of the temple design. They also threw a fundraising party. But by early May 2018, with less than four months to go before Galaxia was due to be unveiled, the architect calculated that he was $168k short.

Knowing that the Silicon Valley elite had a fondness for Burning Man, Mamou-Mani cold-emailed a number of tech titans – Zuckerberg and Musk among them – to see if they could help. He remembers trying different permutations of their email addresses in the hope that one of them would come through.

The wave-shaped wooden boardroom ceiling of Orange HQ in Paris

Fortunately, Google co-founder Sergy Brin replied just an hour later, agreeing to put up the necessary funds as an homage to the recently deceased Harvey. Not only that, Brin would later offer another donation when the project went slightly over budget, as well as visit the construction site to lend a hand with the building. A separate conversation ensued when Brin emailed the architect with a Pinterest board and asked for advice on building a playground for his children.

This was one of many pivotal connections enkindled by Galaxia. Another admirer of the temple was Mikolaj Sekutowicz, a partner at Therme Group, an Austria-based company that designs, builds and operates the world’s largest wellbeing resorts – offering thermal bathing, therapies and health and fitness activities, often in an architectural setting. Mamou-Mani soon came on board as one of Therme Group’s collaborators, and in summer 2021, the group formed a joint venture with the architect to run Fab.Pub, a provider of additive construction and fabrication technology that is currently housed in the back of his London studio.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Galaxia further caught the attention of Karin Gustafsson, design director of fashion label COS, who commissioned Mamou-Mani to build a pavilion from 3D-printed geometric modules for Milan Design Week 2019, called Conifera; as well as Ismail Tazi, co-founder of homeware brand Trame Paris, who recently worked with the architect on a ceramics collection (more on that later). And the chandelier in the oculus would come to inform Mellifera, an installation that graced the atrium of London luxury grocer Fortnum & Mason in 2021.

While business has clearly flourished, Mamou-Mani’s studio retains the dynamism of a start-up. Set in a cluster of containers in the neighbourhood of Cambridge Heath, it has desks and 3D-printers of varying sizes side by side to allow rapid prototyping, and a young team is hard at work, finessing parametrically designed forms and using Silkworm (an open-source plugin that Mamou-Mani co-wrote, which converts CAD forms into printing directions) to turn them into reality. Naturally, there are 3D-printed models on every surface, experiments in form and material composition for both commissions and self-initiated projects. The meeting area table in front is a piece of glass supported on four Conifera modules, and when on my visit in June 2022, it is surrounded by prototypes for the 3D-printed stools soon to be launched by Fab.Pub. They are sturdier than appearances might suggest.

Mamou-Mani in his London studio

Outside are more Conifera modules, deliberately exposed to wind and rain to prove the longevity of PLA, the renewable polymer (made from fermented plant starch) which Mamou-Mani favours for his 3D printing projects. An advocate for sustainable architecture, he mentions that for a 2021 project at London’s Design Museum, he had partnered with French software maker Dassault Systèmes on a life cycle assessment. It showed PLA to have a significantly smaller environmental footprint than ABS, the petroleum-derived plastic widely used for 3D printing; for one, the production of PLA creates 80 per cent less carbon. But the architecture and design industries have been slow to embrace PLA because of doubts over its durability.

‘To recycle PLA, you have to crush it into small pieces and then put it into an industrial composter, which is 60 degrees Celsius with 100 per cent humidity, so enzymes can break down the material. Until you do that, PLA is not going to biodegrade.

‘Separately, there are people who buy PLA objects thinking they’re biodegradable, so when they’re done with it, they just bury it in the garden, or throw it in the waste thinking that it will decompose. That’s also inaccurate. And it’s a shame that such a revolutionary material is so misunderstood.’

Printing in PLA is just one way in which Mamou-Mani is setting the record straight on the material, and stretching its potential. At the moment, the studio uses sugarcane-derived PLA, which he considers suboptimal as the manufacturer grows the plant in Thailand. To eliminate the need for cross-continental shipping, he’s looking into creating PLA from local potatoes and beetroot. He’s also working on educating the end-user: buyers of his 3D-printed stools will be asked to return them to Fab.Pub when they’re no longer needed, so they can be put into the studio’s crusher, industrially composted, and their constituent PLA reused in a new product.

‘Muqar’ vase, by Mamou-Mani for Trame, on view at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris in February 2022

This promise of truly local, waste-free production is what initially drew Therme Group to form its joint venture with Mamou-Mani: it wanted furniture and façades for its wellbeing resorts. Mamou-Mani would send them as pieces of code, which could be received and 3D-printed on-site. This way of working lends itself to endless experimentation: if any element doesn’t work, the architect can tweak the code, resend, and right away an improved version can be printed locally and put in place.

The joint venture will also allow Mamou-Mani to create Fab.Pub locations all over the world, where its 3D printers and recycling facilities can be accessed by the general public. It will ‘enable communities to 3D print their own projects locally, democratising the possibilities of the production process,’ explains Stelian Iacob, senior vice president and COO of Therme Group.

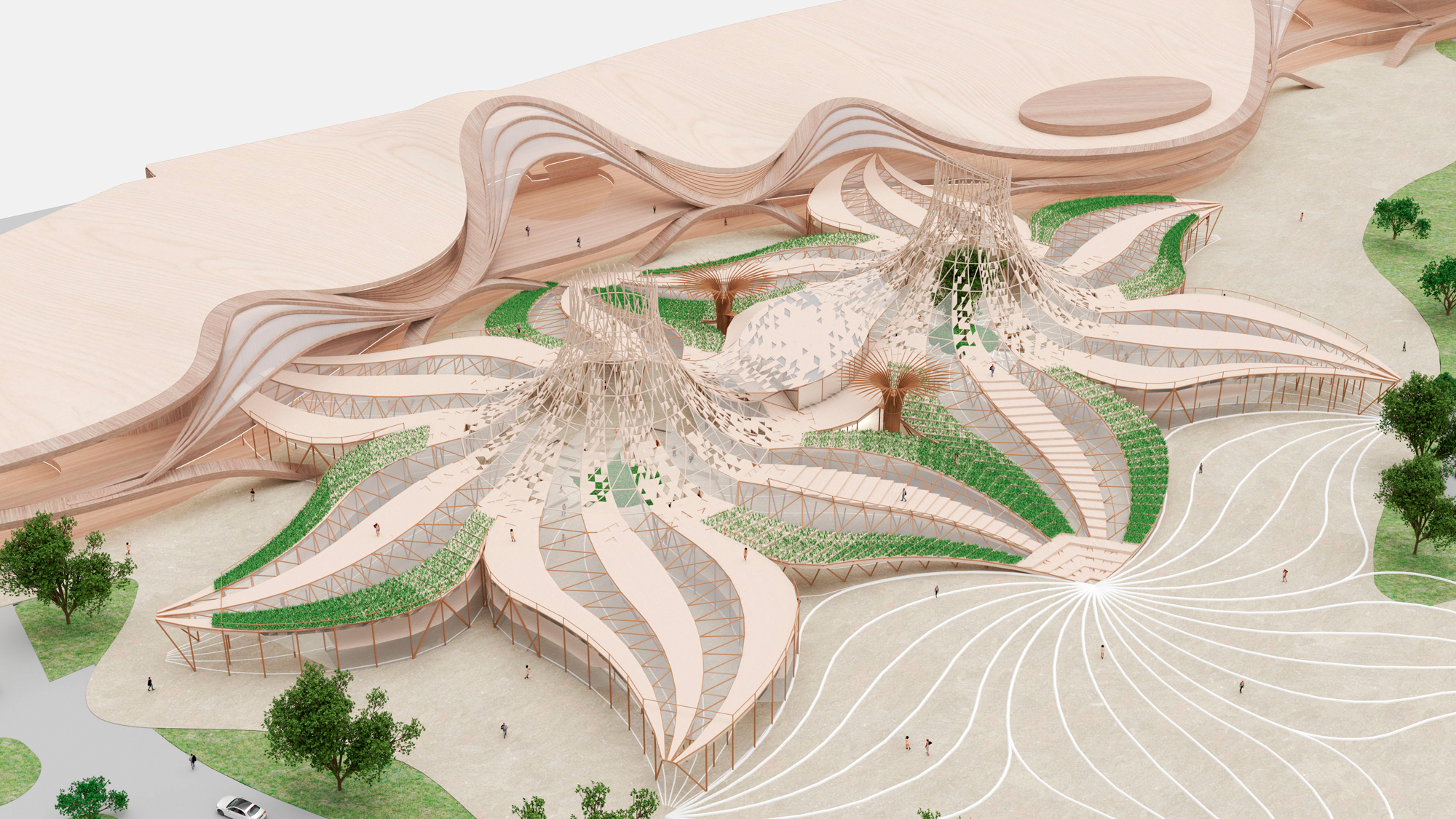

The first of these international Fab.Pubs will be hosted in Speranƫă, a new building in Bucharest that Mamou-Mani has designed for Therme Group, located close to its existing wellbeing resort. The building will comprise two swirling parametric timber structures, called Hope and Time – bearing a resemblance to Galaxia, and accommodating the Fab.Pub as well as spaces for reflection, independent shops, and a restaurant. They stretch out to encompass an open-air amphitheatre, as well as planting to provide natural shade and a biophilic environment for visitors. Over time, the plants will grow to become part of the building itself.

‘Therme wanted two structures that would complement each other, and we came up with two interconnected hexagons that twist. They’re tileable, so we can continue to add structures and different shapes and sizes to create a whole galaxy,’ says the architect, who revealed renderings of Speranƫă for the first time in the August 2022 issue of Wallpaper*. He speaks highly of Therme’s approach to wellness and likens their facilities to Roman thermal baths: ‘they’re almost like temples – there’s a purifying, cathartic element.’

Galaxia, the temple for the 2018 Burning Man festival in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert, was formed of 20 timber trusses that converged in a central spiral and set on fire at the festival’s end

Iacob adds that the design brief for Speranƫă ‘focused on enabling a more personalised experience with the built environment, allowing people to create a relationship with the space rather than imposing it on them. The design creates opportunities for meditation and relaxation, as well as social interaction.’

There are more ambitious architectural projects in the pipeline, both for Therme and other clients. In Bali, Mamou-Mani has designed a lighthouse as part of a new eco village called The Nyanyi Project. The client called to say they had just bought an abandoned colonial bridge made out of ironwood, and wanted to reuse the material. Mamou-Mani reasoned that the material was strong enough to form the structure of a lighthouse, and decided to complement this with a twisting bamboo skin. ‘They were keen to link the structure to natural geometries, so we decided that the twist should follow the golden ratio,’ he says. The tower will be named Bhuma – ‘Earth’ in Sanskrit, and is meant to stand as a beacon of hope.

Looking at Mamou-Mani’s buildings, we can discern a sense of spirituality, and an affinity for nature. I point out that these qualities are not often associated with digitally designed architecture. ‘I think the spirituality comes from the fact that sacred spaces often use natural geometries, and there’s a sort of universality to them,’ he replies. The son of a computer scientist and an environmentalist, Mamou-Mani also points out that computer-generated forms can often bear a closer resemblance to nature than forms drawn by an architect’s hand: ‘computers work from rules and parameters, so whatever you develop will follow a similar process to how a flower grows, following a genetic code.

‘It’s interesting to think of every form not in isolation, but as part of a system. When you start thinking this way, you’re no longer trying to dictate the overall form, but letting things emerge from the parameters you can think of: for instance the materials you use, the structural and environmental constraints. It’s a very humble way to approach architecture.’

A post shared by Camp Catharsis (@camp.catharsis)

A photo posted by on

The intention to create systems rather than isolated structures certainly explains Mamou-Mani’s eagerness to work across multiple scales, within and beyond Fab.Pub. The collaboration with Trame Paris has resulted in a collection called Muqur, previewed in February 2022 at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, and inspired by the honeycomb-like ornamental vaulting (‘muqarnas’) that lines the domes of the Alhambra fortress in Granada. The pieces are 3D-printed on-demand at Fab.Pub and then hand-glazed. Tazi, the brand’s co-founder, points out that given a sufficiently large order (say, ten or 15 pieces of the large vase), they can find a 3D printing studio in the customer’s home country and produce the pieces there. He explains, ‘It makes much more sense, especially when you consider logistical hurdles and costs of international shipping. The design industry needs to find and adapt to on-demand local models – additive manufacturing and 3D printing could be the answer.’

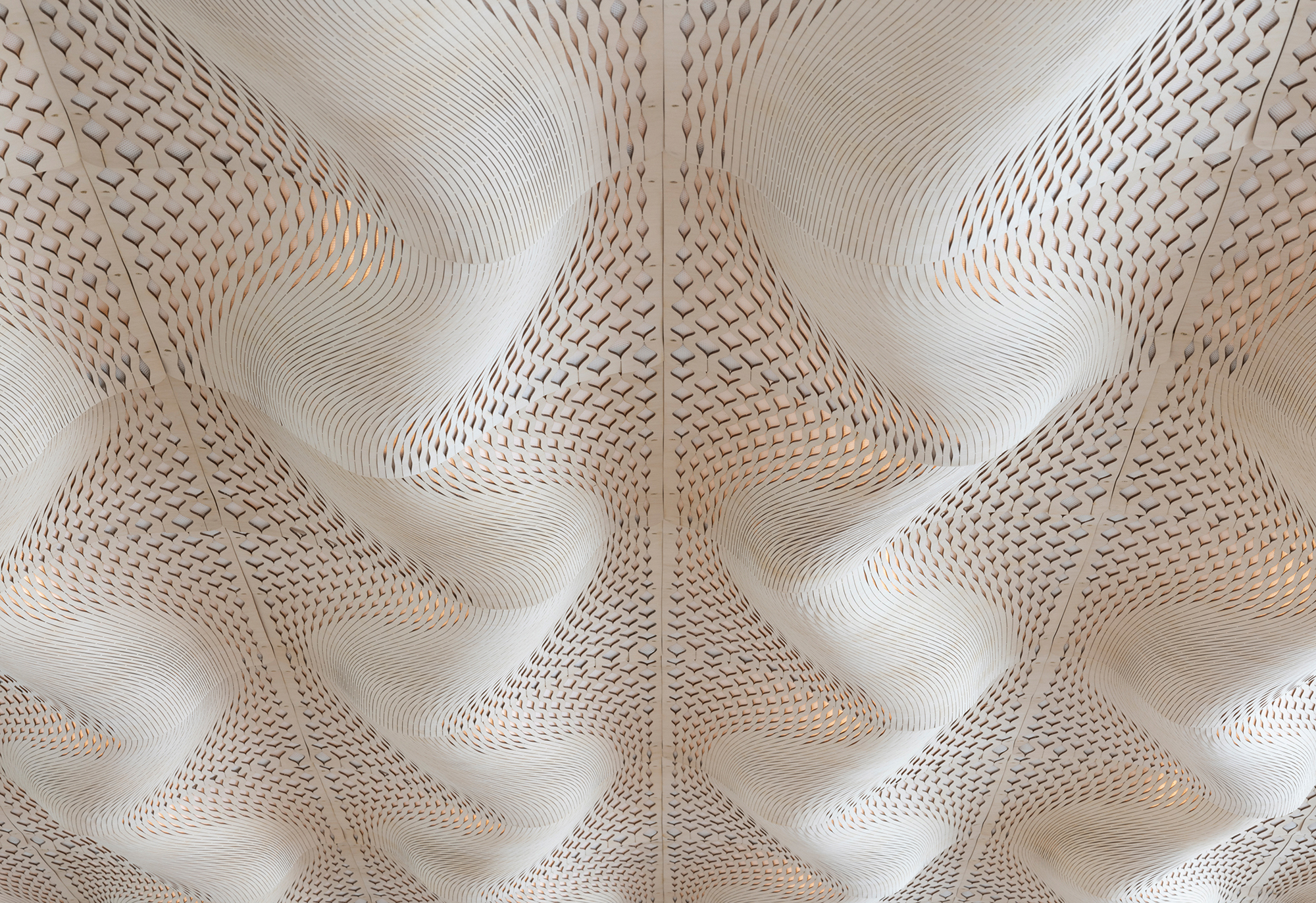

Mamou-Mani recently created three interventions for the Paris HQ of French telecoms company Orange. They include a 150m-long parametric installation emerging from the entrance walls, formed from 4,000 laser-cut zintec sheets; cocoons in steam-bent timber for its workspaces; and a wave-shaped installation for the boardroom ceiling, comprising flat-packed plywood sheets that have been cut with hundreds of lattice hinge to create parametric curves. By introducing these biophilic forms, he hopes to bring a touch of nature into an otherwise corporate space.

The architect is now working on a deeply personal project – his own home, in London’s Stoke Newington, which will consist only of environmentally friendly materials: the walls and ceilings will be made out of clay, and all the furniture will be 3D-printed from PLA at Fab.Pub (which is taking some time, considering how busy it is with commissioned work). ‘It’s been a challenge, but [my wife] Sandy and I are used to making things ourselves rather than buying them. I had 3D-printed her wedding ring after all, and we got married at Burning Man, at the temple I built.’

Speaking of Burning Man, the 2022 festival included a new Mamou-Mani structure, called Catharsis. It wasn’t the Temple, but rather an amphitheatre made from 60 timber modules that followed a fractal pattern. ‘Sometimes in mathematics, you have concepts that are just purely described as mathematical facts: a circle made up of circles, an infinite edge, curvature being smaller than straight lines, and so on. What is interesting is to see their architectural interpretation,’ explains the architect.

The structure comprised seven gateways reaching towards the sky, becoming increasingly intricate and seemingly extending into infinity, forming a set of galleries and performance spaces. Artistic interventions around Catharsis included Refik Anadol’s Machine Hallucinations, a mixed-reality installation that responded to viewers’ neurological brainwaves and invited them to contemplate the meaning of interpersonal wellbeing. Meanwhile, daily happenings included talks, musical performances, a poetry reading, a fire performance, and even a wedding ceremony.

Beyond its solid financial backing (Therme Group paid for the structure, so there was no last-minute fundraising panic), Catharsis differed from Galaxia in that it wasn’t burned down at the conclusion of the festival. It was designed to be easily dismantled and then reassembled on another site – hopefully London’s Somerset House, Mamou-Mani says – and possibly go on a world tour. ‘One of the other principles of Burning Man is radical inclusion. And what could be more inclusive than bringing your structure to people who otherwise can’t visit?’

TF Chan is a former editor of Wallpaper* (2020-23), where he was responsible for the monthly print magazine, planning, commissioning, editing and writing long-lead content across all pillars. He also played a leading role in multi-channel editorial franchises, such as Wallpaper’s annual Design Awards, Guest Editor takeovers and Next Generation series. He aims to create world-class, visually-driven content while championing diversity, international representation and social impact. TF joined Wallpaper* as an intern in January 2013, and served as its commissioning editor from 2017-20, winning a 30 under 30 New Talent Award from the Professional Publishers’ Association. Born and raised in Hong Kong, he holds an undergraduate degree in history from Princeton University.