Explore the work of Jean Prouvé, a rebel advocating architecture for the people

French architect Jean Prouvé was an important modernist proponent for prefabrication; we deep dive into his remarkable, innovative designs through our ultimate guide to his work

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Jean Prouvé (1901–1984) occupies a singular position in 20th-century architecture and design. Neither architect in the orthodox sense nor industrial designer by training, he described himself instead as a constructeur, a 'builder' for whom the act of making, assembling and improving was inseparable from ethics. Best known today for his metal furniture and pioneering prefabricated buildings, Prouvé’s importance lies less in a recognisable style than in a conviction that design should respond directly to social need. Few modernist architecture masters managed to fuse politics, craftsmanship and construction with such clarity. Fewer still did so while remaining rooted in one city: Nancy, where this creative's ideas were formed, tested, and, in many ways, lived out.

Jean Prouvé in 1981

Who was Jean Prouvé?

Born in Nancy in 1901, Prouvé grew up in a household shaped by progressive artistic ideals. His father, Victor Prouvé, was a leading figure of the École de Nancy, one of the epicentres of France’s Art Nouveau movement that linked beauty to social reform and craft to industry. This environment instilled in Jean a respect for labour and material intelligence rather than academic theory. Rejecting formal architectural education, he trained as a metalworker, learning through fabrication, failure and iteration.

Jean Prouvé: origins

That practical grounding shaped both Prouvé's personality and his politics. He was outspoken, stubborn and deeply principled, resistant to authority when it conflicted with his moral compass. During the Second World War, these qualities found concrete expression: he joined the French Resistance, placing his technical skills at the service of a broader struggle against occupation. Shortly after liberation, he briefly became mayor of Nancy, a symbolic civic role that reflected both his wartime commitment and the trust he commanded locally. It was a fleeting political chapter, but one that reinforced his belief that building, governance and social responsibility were inseparable.

The Metropole house was designed as a mass-producible rural school with classroom and teacher accommodation

Nancy: workshop, city and testing ground

Nancy was not merely Prouvé’s birthplace but the engine of his thinking. Set in the eastern heartlands of French heavy industry, Nancy had long forged itself as a place where manufacturing (particularly metalwork) fused with beauty, the École de Nancy being a product of this. It was also a city with strong traditions of social reform and offered fertile ground for his ambitions. In the 1930s, he established his own workshops there, producing everything from furniture and façade panels to structural components and experimental housing. Unlike many modernists, Prouvé did not separate architecture from production; design happened on the workshop floor as much as on the drawing board.

The city also shaped his understanding of scale and responsibility. Prouvé was less interested in monumental gestures than in repeatable solutions: doors, joints, roofs, frames — the elements that could be standardised, improved and deployed widely. Nancy allowed him to test ideas at a civic scale, responding to schools, housing shortages and post-war reconstruction with pragmatism rather than ideology.

The Jean Prouve/Richard Rogers suite’s midcentury furniture at Chateau La Coste includes 'Square Table' (1952-56) and 'Easy Armchairs' by Pierre Jeanneret (ca. 1955-56), cabinet 'Bahut BA 12' by Jean Prouvé, and a lamp by Serge Mouille (1953).

Historical context

Prouvé’s career unfolded in parallel with some of the century’s most urgent crises. Before the war, he gained recognition for metal furniture that translated structural logic into domestic form: chairs and tables where strength, economy and comfort were all too visible. After 1945, his focus intensified around housing, driven by the acute shortages facing France. He developed lightweight, prefabricated systems intended to be transported, assembled and disassembled with ease, emphasising speed, dignity and efficiency.

It was in this context that his collaboration with Abbé Pierre emerged, culminating in the Maison des Jours Meilleurs (House of Better Days) in 1956 — a project that distilled Prouvé’s humanitarian ideals without spectacle. While bureaucratic resistance ultimately limited its dissemination, the project stands as a powerful expression of architecture conceived as an emergency response rather than an aesthetic exercise. That said, to contemporary eyes and taste, Prouvé’s designs are more than a little aesthetically pleasing and desirable.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Gallerist and Jean Prouvé authority Patrick Seguin went into an unassuming sex club in Nancy and found Prouvé's long-lost Maxéville Design Office. Courtesy Galerie Patrick Seguin (as originally featured in the July 2016 issue of Wallpaper*, W*208)

Throughout these years, Prouvé’s relationship with industry was complex. He believed in mass production but resisted its tendency to dilute authorship and ethics. Being forced out of his own company in the early 1950s was a personal blow, yet it did not weaken his influence. Later roles within large industrial groups allowed him to continue refining systems and advising on construction at scale, even as his most radical ideas often outpaced institutional comfort.

Jean Prouvé's Maxéville Design Office in the warehouse of Galerie Patrick Seguin (from feature, as above)

Legacy and relevance

Jean Prouvé’s legacy has only sharpened with time. In an era preoccupied with climate responsibility, housing inequality and resource scarcity, his insistence on an economy of means feels strikingly current. Architects from Renzo Piano to Parisian studio Lacaton & Vassal have acknowledged his influence, particularly his belief that generosity can be structural rather than symbolic.

Yet Prouvé resists easy canonisation. His work is demanding, sometimes austere, and unapologetically utilitarian. What endures is not an image but an attitude: a refusal to separate construction from conscience. Rooted in Nancy, forged in resistance, and sustained by compassion, Prouvé’s career offers a reminder that modernism, at its best, was never only about form — but about building better days for everyone.

8 key projects

Maison des Jours Meilleurs (House of Better Days), 1956

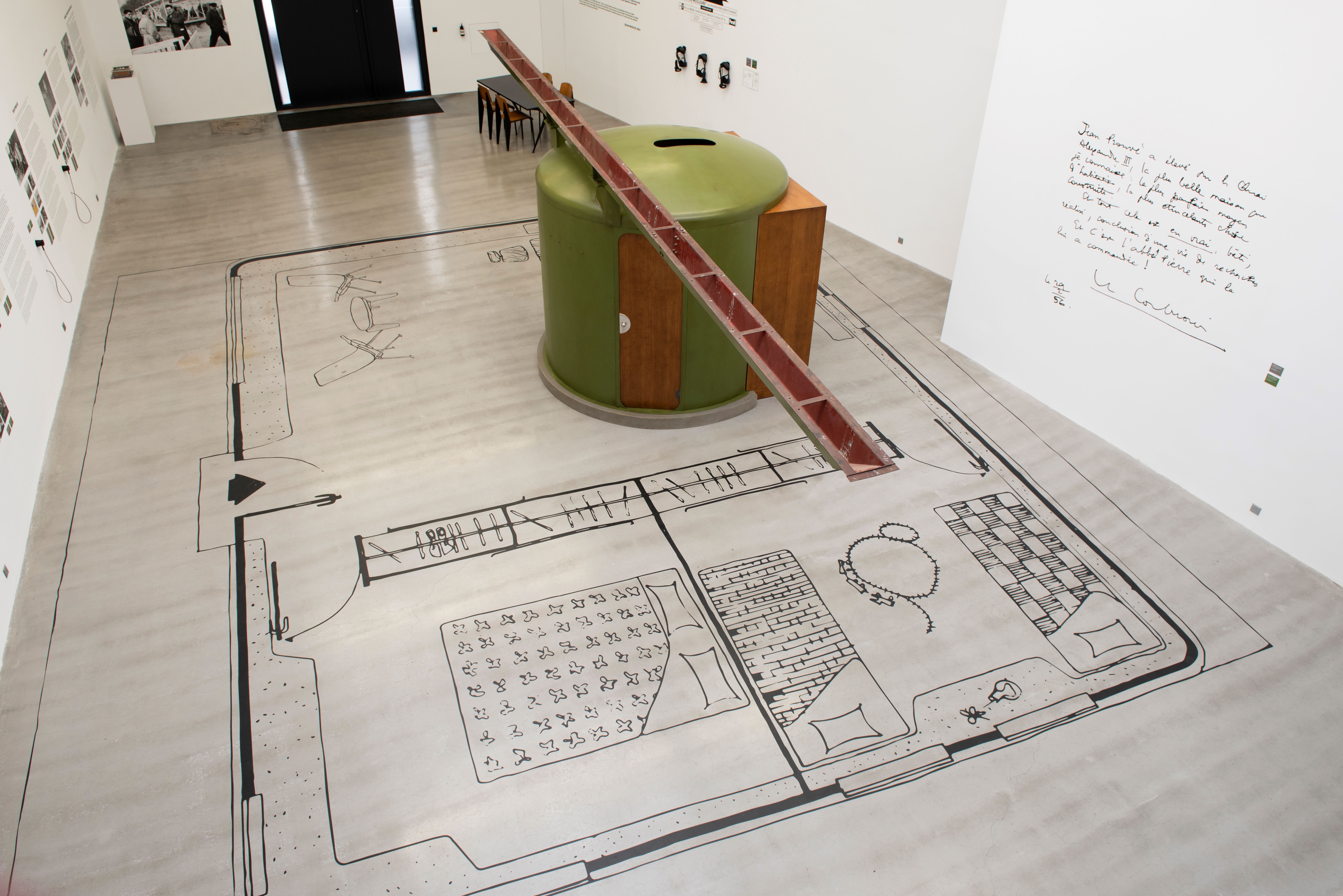

'House of Better Days' on show at Galerie Patrick Seguin in Paris in 2024

Designed for Abbé Pierre in response to France’s post-war housing emergency, this demountable dwelling distilled Jean Prouvé’s belief that architecture should act quickly and humanely. Conceived for rapid assembly, transport and affordability, it rejected symbolism in favour of dignity. Though never mass-produced at scale, it remains a powerful expression of architecture as social responsibility rather than formal display. In 2024 Paris’ Galerie Patrick Seguin held a show devoted to the Maison Les Jours Meilleurs.

Maison Prouvé, Nancy, 1954

Built for his own family on a hillside in Nancy, this lightweight house functioned as a personal manifesto. Prefabricated aluminium panels, a steel portal frame and dry assembly created a domestic environment defined by efficiency and adaptability. Neither experimental prototype nor showcase villa, it embodied Jean Prouvé’s conviction that innovation belonged in everyday life, not architectural spectacle.

Maison du Peuple, Clichy, 1939

Co-designed with Eugène Beaudouin and Marcel Lods, this pioneering civic building combined a market, assembly hall and offices within a flexible structural system. Retractable floors, sliding walls and exposed metalwork reflected a radical approach to public architecture. Prouvé’s contribution lay in translating social ambition into mechanical ingenuity, allowing the building to adapt to collective use.

Standard Chair, 1934

This seemingly simple wooden chair reveals Prouvé’s understanding of force and material logic. Thick rear legs bear the load, while slimmer front legs reduce unnecessary mass. The result is economical, robust and visually honest. Far from decorative furniture, the Standard Chair exemplifies Prouvé’s belief that good design begins with structure over style.

Demountable Houses (6×6 and 8×8), late 1940s

Developed to rehouse displaced populations after the war, these compact dwellings prioritised speed, clarity and reuse. Made from prefabricated elements, they could be erected with minimal labour and dismantled without waste. These projects framed housing as an urgent logistical challenge, reinforcing Prouvé’s stance that construction systems, not forms, define architectural progress. In 2018 Galerie Patrick Seguin immortalized Prouvé’s Demountable House by installing it at Château La Coste.

Aluminium Furniture for Cité Universitaire, Paris, 1952

Produced for student housing in Paris, this series explored aluminium as a lightweight, durable material suited to communal living. The pieces were stackable, resilient and easily repaired, reflecting Jean Prouvé’s attention to an object’s lifecycle rather than appearance. Furniture here functioned as infrastructure, supporting everyday use while elegantly demonstrating the possibilities of industrial production.

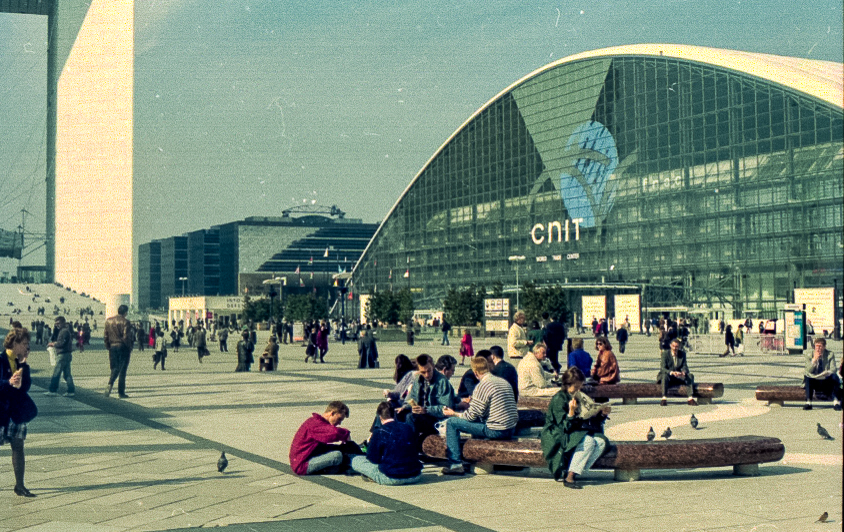

CNIT Roof Structure, La Défense, 1958

Working as an engineer and consultant, Prouvé contributed to the vast concrete shell of the CNIT exhibition hall. The project marked his engagement with large-scale construction and structural daring. Though less intimate than his housing work, it showed his capacity to apply principles of efficiency and load distribution to monumental contexts without abandoning technical rigour.

Façade Systems and Industrial Panels, 1950s–60s

A post shared by FORD (@fordstudio_)

A photo posted by on

Across multiple projects, Prouvé developed curtain walls, panels and envelope systems that prioritised assembly logic and performance. These components, often overlooked beside his buildings and furniture, encapsulate his thinking most clearly. Architecture, for Prouvé, was a sum of parts and improving those parts was a political as well as technical act.

David is a writer and podcaster working (not exclusively) in the fields of architecture and design. He has contributed to Wallpaper since 2022 when he wrote about the late, postmodernist architect and founder of the Venice Architecture Biennale - Paolo Portoghesi reporting from his home outside Rome. In 2024, David launched Arganto - Gabriele Devecchi Between Art & Design, a podcast exploring the life and legacy of this Milanese silversmith and design polymath.