Anupama Kundoo on Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi’s legacy

Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi's recent passing shook the global architecture community; here, leading Indian architect Anupama Kundoo looks back at his legacy

Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi, a prolific architect and educator, has left behind a huge legacy for generations to come. He studied in Mumbai, and famously worked with modernist architecture masters Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn, before founding his own practice Vastu-Shilpa from his studio Sangath in Ahmedabad. He continued his work there for over six and a half decades, until he passed away on 24 January 2023, having designed numerous realised and unrealised projects.

Balkrishna Doshi's even greater contribution to architecture was his deep and consistent personal engagement with the architectural community at large and the profession as a whole. In 1962, he founded the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (CEPT), School of Architecture in Ahmedabad as a one-of-a-kind educational facility, enabling an unprecedented meeting place for direct encounters between young learners and accomplished professionals from across the globe. He remained personally approachable to one and all, and continued to directly engage with students and colleagues in the field throughout. He was also the architect of this school’s building (without doubt one of his best works), a perfect balance between the inside and the outside, contemplative and social, formal and informal spaces ‘celebrating life’ in all its complex aspects, and in sync with his description of good architecture. His lectures, research and writing facilitated dialogue in much the same way.

Remembering Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi (1927 – 2023)

My own interactions with Doshi steadily increased since 1998, in connection with my growing engagement in the planning work for the international city of Auroville in South India, in collaboration with its chief architect Roger Anger. I had started my architectural practice in Auroville in 1990, and in 1996 I was a recipient of the Vastu Shilpa Foundation research fellowship for my research titled ‘Urban Eco-Community: Design and Analysis for Sustainability’. Thereafter, during my involvement in producing Auroville’s masterplan in 1999 for approval by the Ministries of Urban Development and Human Resource Development (under which Auroville Foundation is positioned), I had approached Doshi for guidance. He would receive me warmly at his studio and home, and I had the good fortune of staying over in both those places. He too visited us in Auroville on several occasions and I facilitated meetings between him and Anger, and others involved in Auroville’s planning. He would always bring snacks and goodies from Ahmedabad when he visited or give me something to take back from Ahmedabad when I visited, leaving a lasting impression of his porous boundaries as a warm and social human being with whom it was easy to connect on a human level, as when collaborating on a professional one.

Conversations with him and his wife Kamala over meals made us feel at home, like there was no distance necessary between people. When he came to Auroville, he too visited me at my residence Wall House, and made it a point to meet my father and my bedridden ailing mother who lived with me in Auroville during their last years. We kept in touch even after Anger passed away in 2008, and soon after Doshi was appointed as a member of Auroville’s governing board for two cycles of four years each. Doshi deeply admired and appreciated Anger and saw a great promise in his visionary ideas and unique city plan. As chairman of the Auroville Town Development Council (ATDC), he eagerly supported the same line of development as envisaged by Anger. As current head of Urban Design at ATDC, I was looking forward to our ongoing interaction along with the Board of Experts that is now in the process of being set up. He had accepted to be part of this board. Thanks to post-Covid digital platforms on which we met, the recorded interactions with him will inspire further work and decisions being taken in realising Auroville.

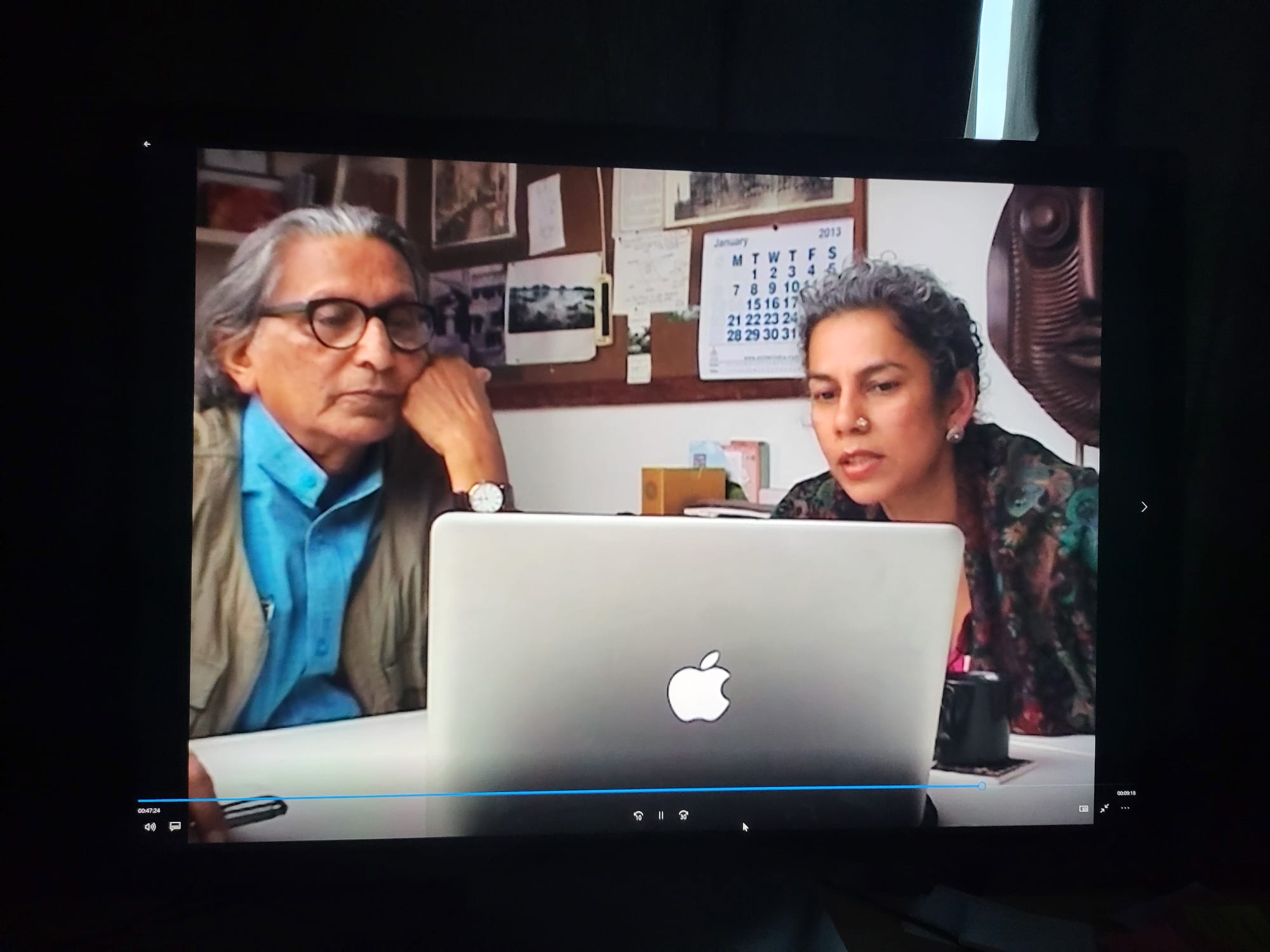

Anupama Kundoo and Balkrishna Doshi

His expansive contribution was recognised through India’s highest honours, Padma Shri and Padma Bhushan. He was also a recipient of the Aga Khan Award. Much more recently, in his nineties, Doshi received the Pritzker Architecture Prize 2018 for his substantial contribution to the field of architecture, and the RIBA Gold Medal 2022. While many felt that these international awards came in too late, they were nonetheless timely, as what Doshi stood for is important the world over now more than ever. The timeless values and holistic approaches that he represents personally and professionally are exactly what needs to be globally acknowledged as architectural best practice. Everywhere. At a time when architecture is being reduced to seductive building forms and photogenic façades that are air-dropped into diverse contexts, regardless of their complex local cultural or climatic context, where over-simplified computer-generated renderings and often frivolous play of forms are becoming the norm, I was personally overjoyed that the Pritzker committee’s decision brought the attention back to architecture’s real capacity to facilitate and create environments that are human society-centric.

Doshi’s body of works shows that outstanding contemporary buildings can be expressions of deeper cultural values of a collective, that architecture is the synthesis of many complex concerns, and above all a backdrop for life to take place, where the architect is at the service of human society.

Still from film by Marta San Vicente

As an educator, and an engaged member in society, Doshi has inspired generations of students and architects from the world over to share experiences freely, just as on a personal level his home has been equally open to all. Despite his success and fame, he has always been accessible and inclusive, and treated people regardless of age and experience at par. He may be one of the eldest architects to have been honoured with prizes like the Pritzker, but his spirit is probably the youngest. Those who have interacted with him will agree that his youth, curiosity and openness were inspirational.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

While architects the world over are celebrating him and the universal values they see in him, I am glad that the global community will equally take the time to discover more about his work and legacy, and perhaps rethink where contemporary architecture is headed.

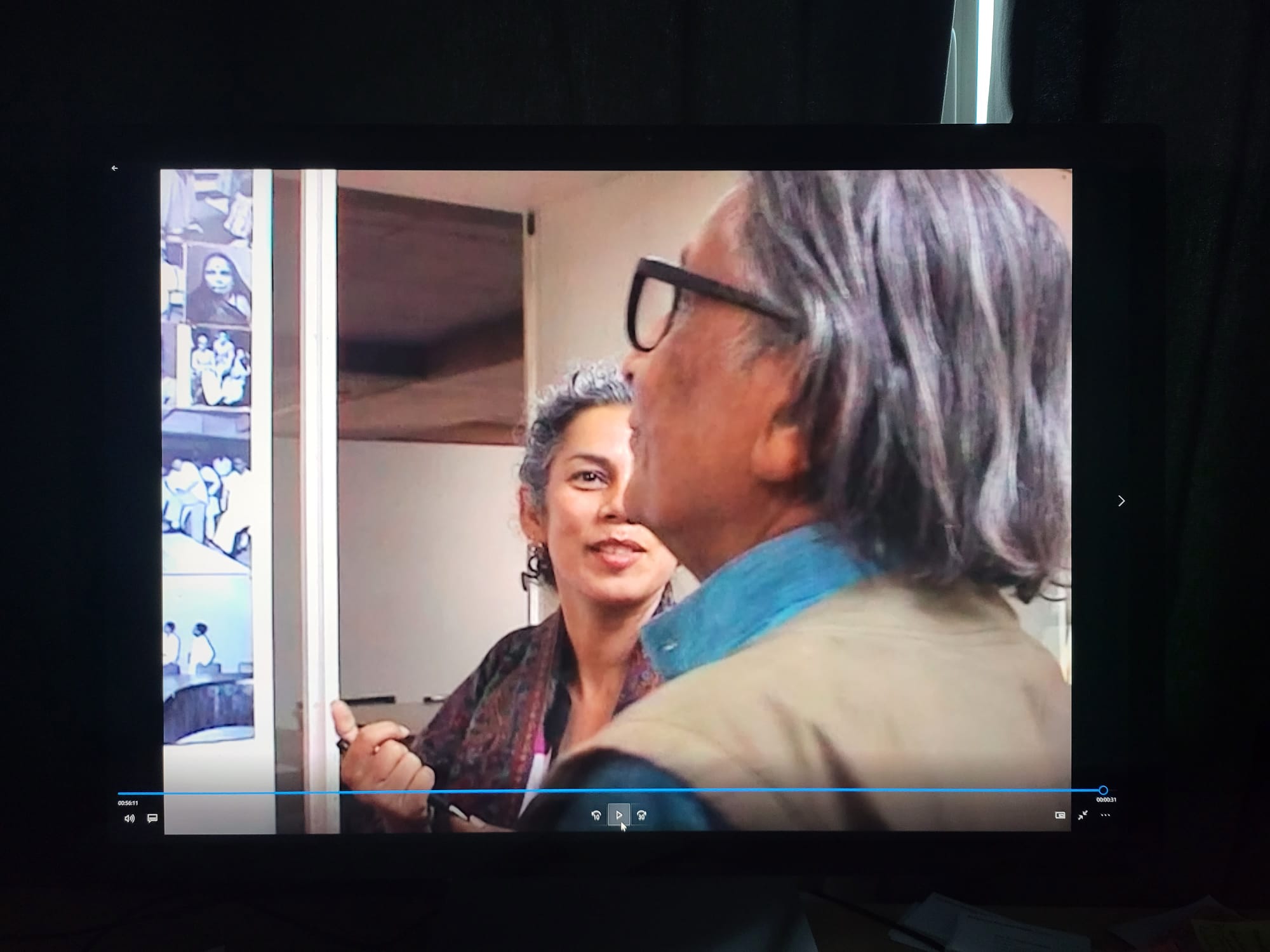

Still from film by Marta San Vicente

Conversations with him smoothly crossed over between the practical and the philosophical, the professional and the personal. I remember on one occasion, when I had been sharing some of my recent projects and research on my laptop under the title of ‘Form follows Technology’, and had mentioned the context of my ferrocement research [a profile on Anupama Kundoo published in Wallpaper's April 2021 issue, discusses her work in detail], saying that the architecture was ‘site-specific’, he responded thoughtfully: ‘…actually architecture is life-specific’. These are Doshi’s words that encompass the summary of all my discussions with him. That architecture is life-specific.