'Total work of art': Taschen's single volume Frank Lloyd Wright monograph

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

FLW used to be a mainstay of the architectural publishing industry. In the pre-digital era, before the monograph became the calling card of the emerging practice and not a studious look back at a lengthy career, the most popular architect in the ‘design’ section was the irascible, foppish, arrogant but eternally creative Frank Lloyd Wright, a man whose career spanned seven decades and over 500 buildings.

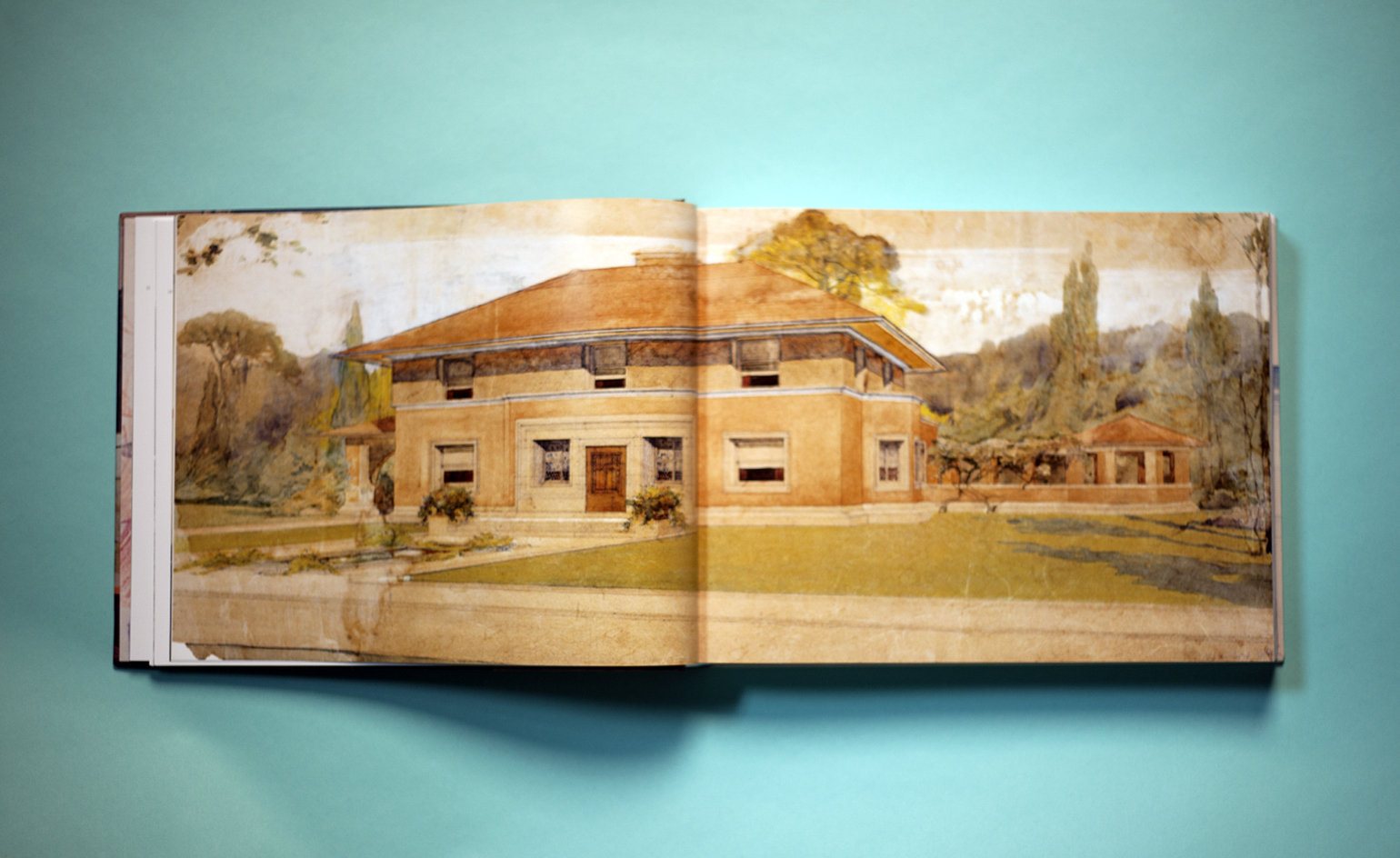

Wright’s enduring popularity is down to many factors, his quality of work notwithstanding. He was a skilled self-publicist, the author of many books. He cultured a guru-like following amongst his staff and students, especially at the Taliesin schools he established. His ‘total work of art’ approach extended down to the smallest detail, creating houses of such visual richness, craftsmanship and invention that they stand apart from the art movements that may or may not have influenced them. And his presentation was second to none. In addition to 500 completed works, there were as many unbuilt, all surviving in the characteristically beautiful drawings and watercolours that he used to seduce clients and historians alike.

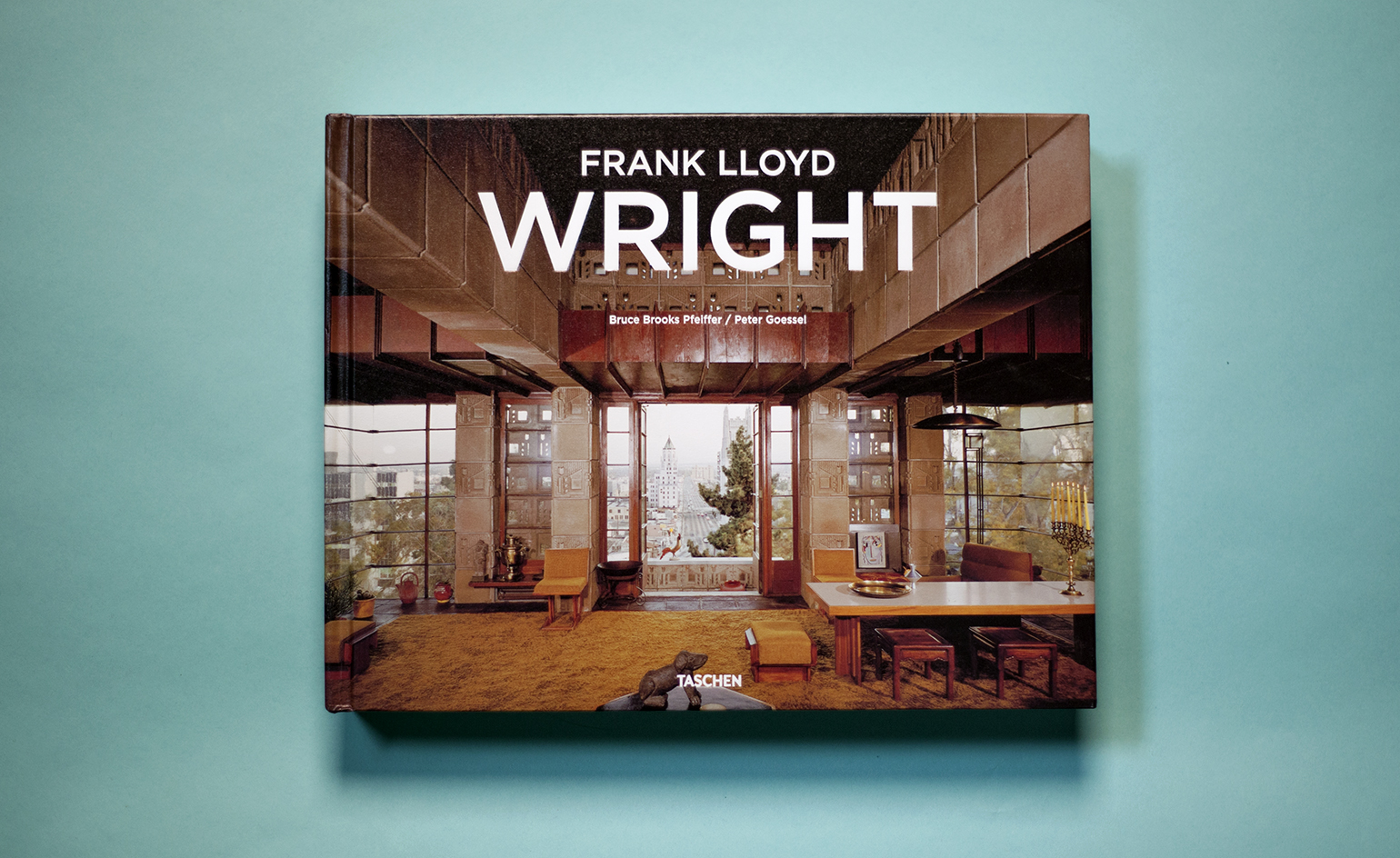

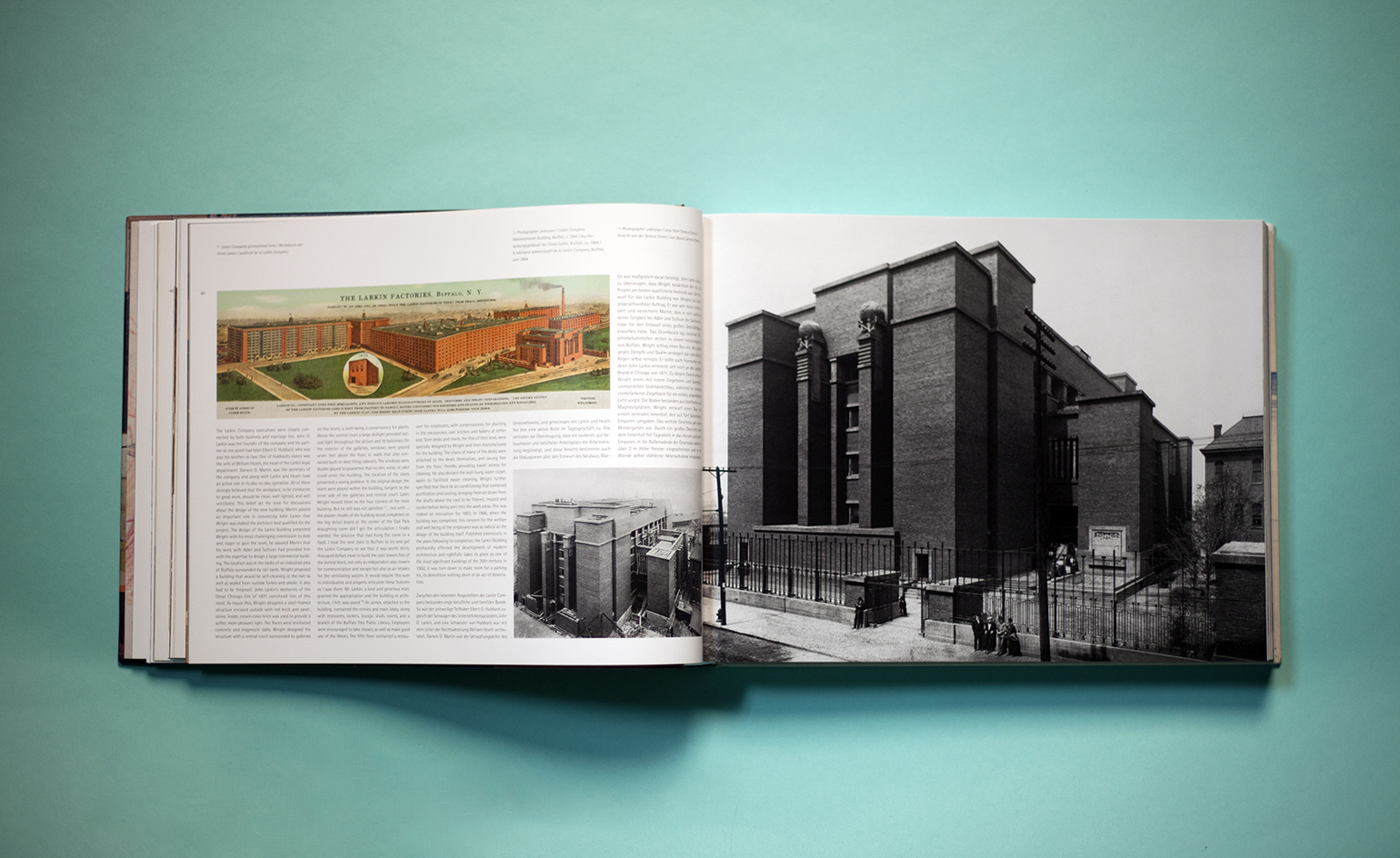

Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer is our era’s pre-eminent Wright specialist, having begun his career as Wright’s apprentice. Now archives director at Taliesin West, he has access to hundreds of thousands of documents, allowing this monograph to be a masterful summation of FLW’s long career. Compiled from Taschen’s vast three-volume oeuvre complète, this single volume is a greatest hits and more, covering everything from the elegant houses built around Chicago’s Oak Park, with their long, low ‘Prairie Style’ proportions and elaborate detailing, through to the pioneering Larkin Administration Building – oft cited as the world’s first modern office block – and the more expressive, space age futurism of his later work. There is more than enough here to make this the ultimate compact work on a definitive character in architectural history.

From the book: William Winslow House, River Forest, Illinois, 1893. This was Wright's first realised commission as a recognised independent architect and anticipates his later homes for the Midwest American prairie. Pictured here is the perspective drawing

Susan Lawrence Dana House, Springfield, Illinois, 1902. From left: Susan Lawrence in front of her house; glass and bronze table lamp, 2002. Right: street view of the house, 1997

Larkin Company Administration Building, Buffalo, New York, 1903 – Wright's most challenging commission to date. Left: a promotional item for the building. Right: a view from Seneca Street

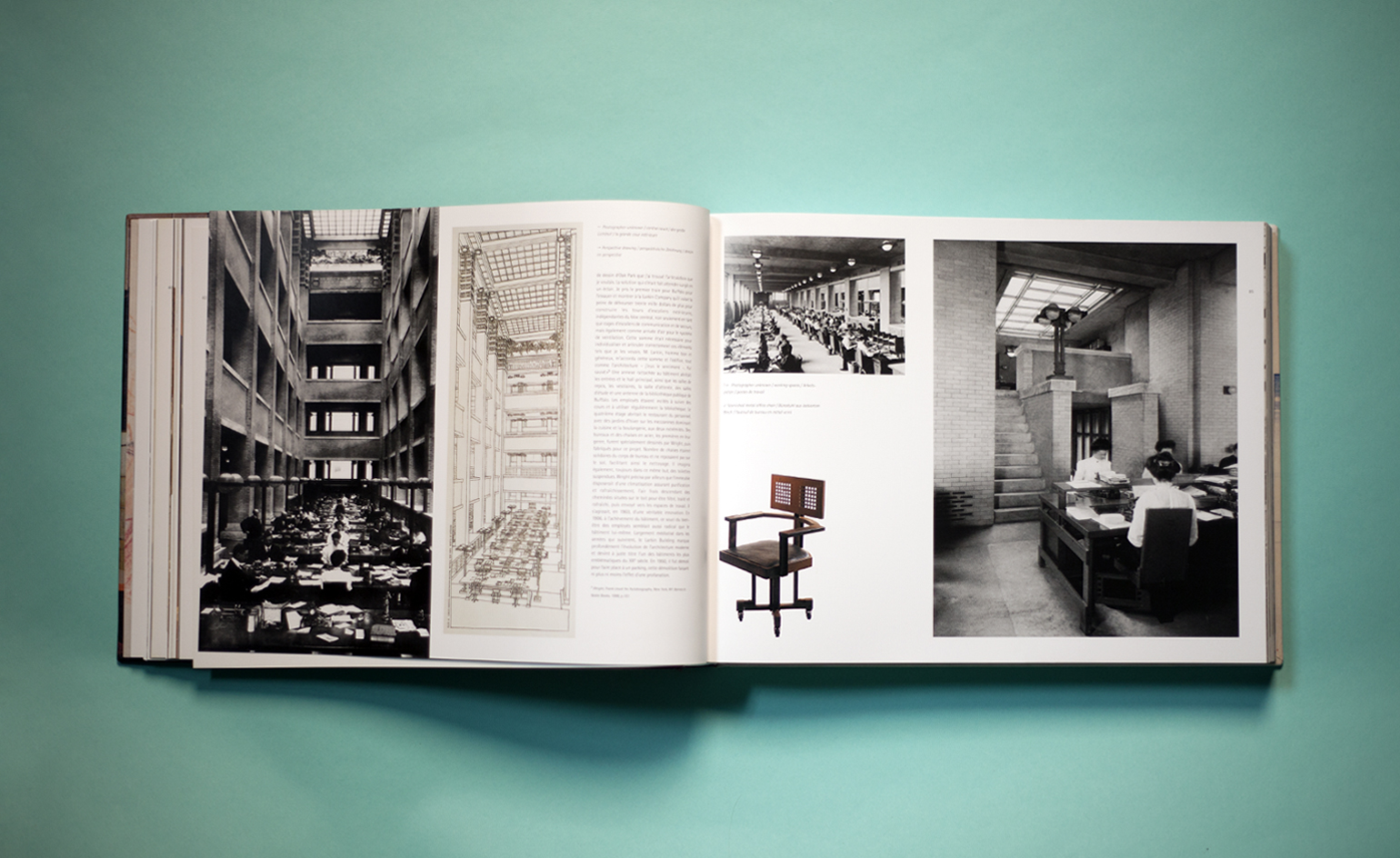

Inside of the Larkin Company Administration Building. Left: central court and the initial perspective drawing. Right: working spaces and a varnished metal office chair

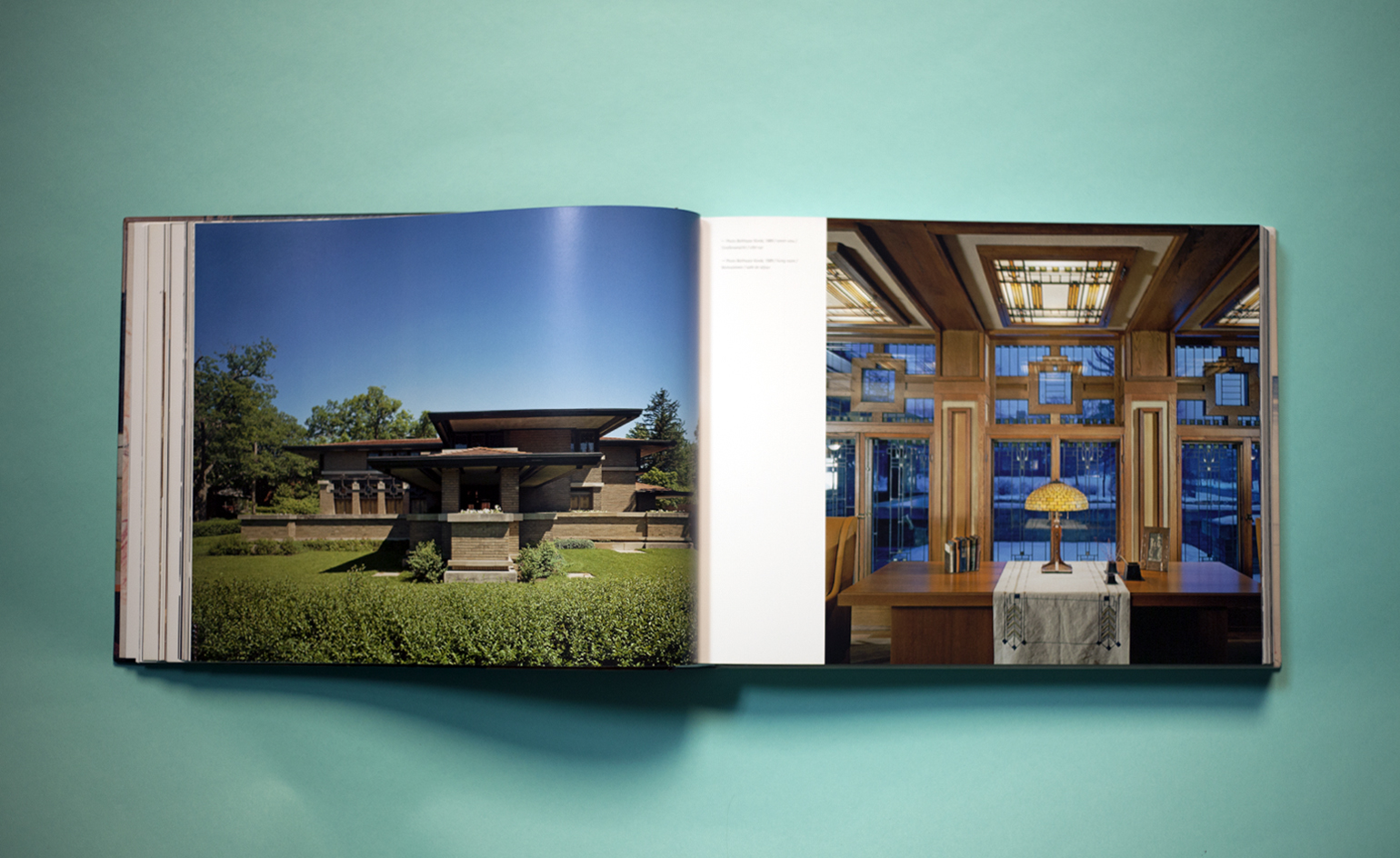

Meyer May House, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1908. The architect has made the movement within the building circuitous. Left: the street view of the house in 1989. Right: the elegant living room.

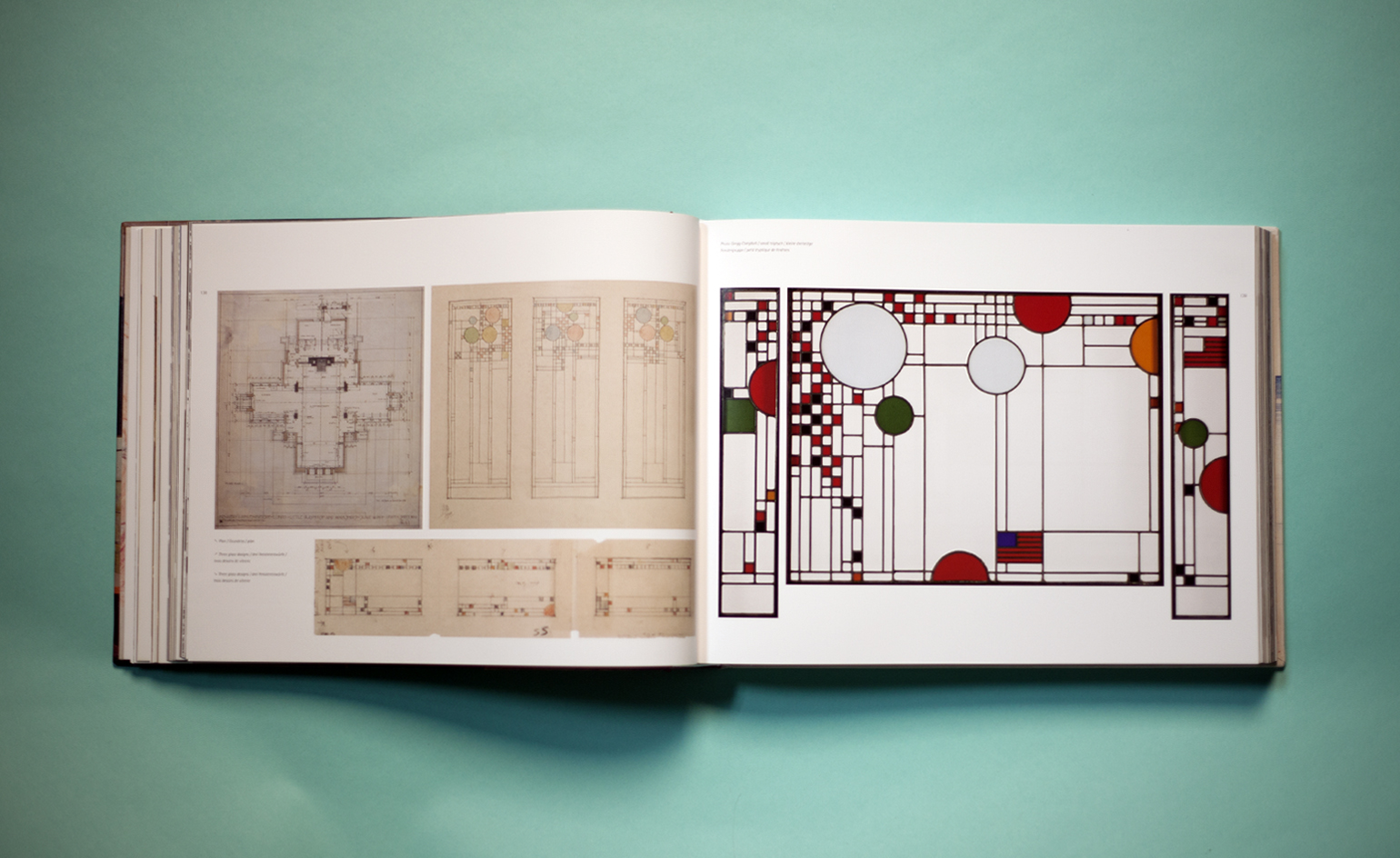

Avery Coonley Playhouse, Riverside, Illinois, 1912. Left: glass designs for the windows. Right: the small triptych colour design.

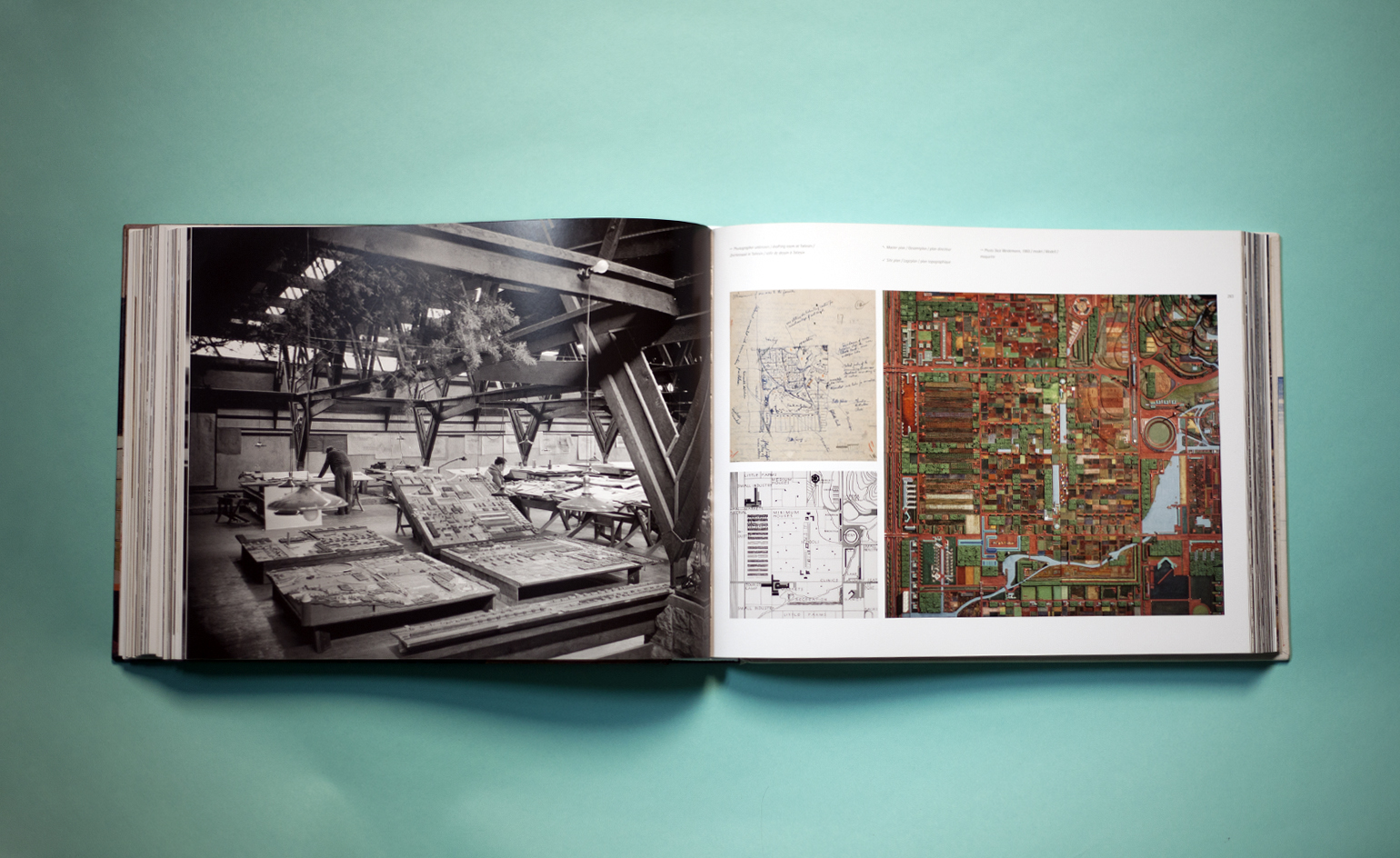

Broadacre City, the model, 1934. Left: model in the drafting room at Taliesin. Right: the master plan alongside site plan and detailed model

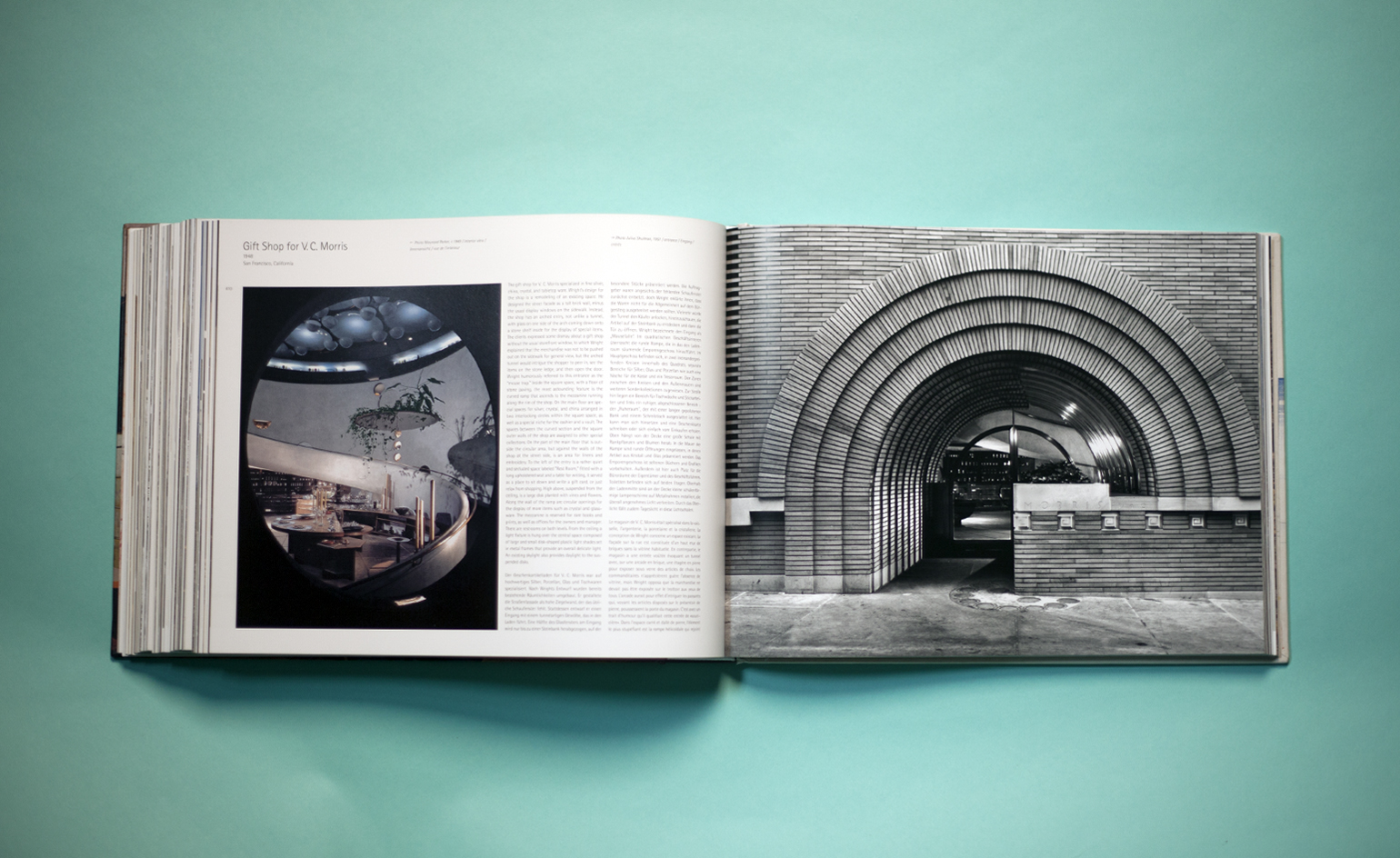

Gift shop for VC Morris, San Francisco, California, 1948. Wright's tunnel like design was a remodel of an existing space. Left: the interior view, 1949. Right: The entrance in 1951, which Wright humorously referred to as a 'mouse trap'.

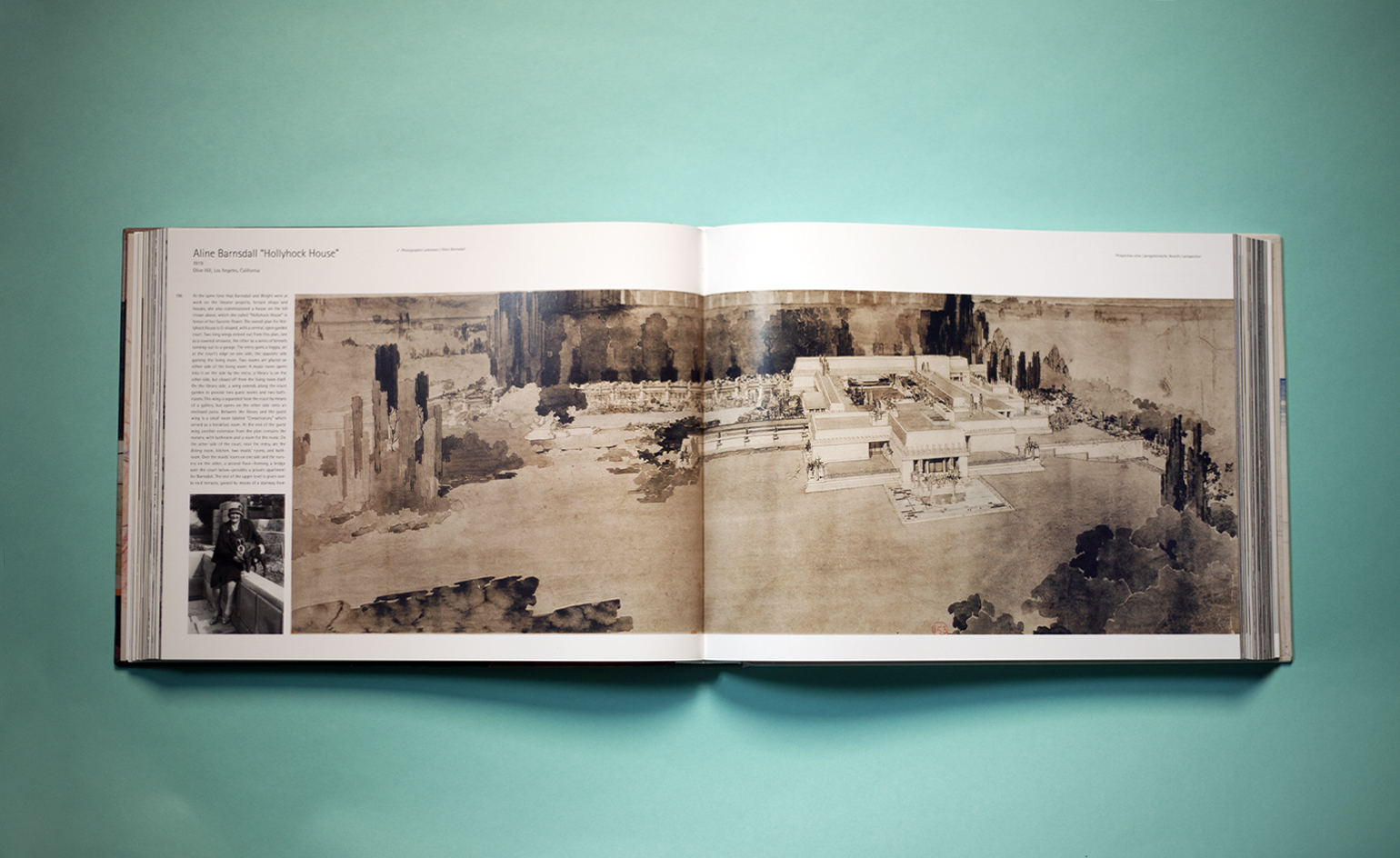

Aline Barnsdall's 'Hollyhock House', Olive Hill, Los Angeles, California, 1919. Named after Barnsdall's favourite flower, this U-shaped house was commissioned alongside theatre projects, terrace shops and houses

INFORMATION

Photography: Hanna Pasanen

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.