Design & Interiors

Travel with us to design weeks and experience refined interior design from across the globe. Get the first look at all-new modern furniture, and contemporary craft every day

Explore Design & Interiors

-

Puiforcat brings something new to the table with a wooden cutlery set

Jasper Morrison's collection for Puiforcat features cherry wood cutlery finished with fuki-urushi lacquering, a first foray into wood for the silverware company

By Hugo Macdonald Published

-

In Copenhagen, Charlotte Taylor gave us a glimpse into the mess of real life

At 3 Days of Design, Charlotte Taylor staged ‘Home from Home’, a group exhibition in collaboration with Noura Residency, showcasing the chaos of the everyday, from unmade beds to breakfast leftovers

By Laura May Todd Published

-

Stephen Burks and Malika Leiper transform everyday mats into sculptural seating in Senegal

Using woven plastic mats and zip ties, the New York designers explore local vernacular and creative adaptation at the Albers Foundation’s Thread residency

By Ali Morris Published

-

This designer is revitalising the lost folk tradition of Ukraine’s painted cottages

Through gleaming hammered-steel panels, Victoria Yakusha is opening a dialogue about ancestral memory, craft and womanhood

By Anna Fixsen Published

-

Dine within a rationalist design gem at the newly opened Cucina Triennale

Cucina Triennale is the latest space to open at Triennale Milano, a restaurant and a café by Luca Cipelletti and Unifor, inspired by the building's 1930s design

By Anne Soward Published

-

‘100 Years, 60 Designers, 1 Future’: 1882 Ltd plate auction supports ceramic craft

The ceramics brand’s founder Emily Johnson asked 60 artists, designers, musicians and architects – from John Pawson to Robbie Williams – to design plates, which will be auctioned to fund the next generation of craftspeople

By Malaika Byng Published

-

Studiomama’s cast faces capture a sense of childlike joy

Made in collaboration with one of London’s last traditional foundries, the studio’s ‘Face Castings’ series explores play, perception and the enduring influence of Bruno Munari

By Ali Morris Published

-

Lois Samuels’ ceramics invite us to find beauty in imperfection

On view at Twentieth in Los Angeles, the artist’s unglazed ceramics explore ‘life’s intricacies and magic’, she says

By Mazzi Odu Published

-

Five of our favourite furniture reissues from 3 Days of Design 2025

At the Copenhagen event, several brands brought masterpieces from the past back to life – here’s our pick of the furniture revivals, from sofas to lighting

By Hugo Macdonald Published

-

Lulu Harrison is the Ralph Saltzman Prize winner 2025

The Design Museum, London, announces Lulu Harrison as winner of The Ralph Saltzman Prize for emerging designers, and will showcase her work from 24 June to 25 August 2025

By Tianna Williams Published

-

Reimagining roots: highlights from Design Shanghai 2025

The 12th edition of Design Shanghai reflected the evolution of Chinese creativity despite challenges to the sector, with participants exploring the intersection of tradition and innovation

By Yoko Choy Published

-

3 Days of Design 2025: live updates from the Wallpaper* team

From 18-20 June, design is taking over Copenhagen. Follow along with the latest news, launches and other goings-on from 3 Days of Design, as seen by Wallpaper* editors.

By Hugo Macdonald Last updated

-

Inside MAZE Design Basel the city's new design fair

With only 11 exhibitors and the backdrop of a Swiss Gothic Revival church, MAZE Design Basel is a new intimate art fair for those in the know

By Brian Ng Published

-

Designer Alex Proba teams up with Hoka for a delightfully colourful shoe collab

This maximalist footwear capsule is designed to get dirty

By Anna Fixsen Published

-

The owner of this restored Spanish Colonial home turned it into a gallery – with no social media allowed

Casa Francis in LA is a private residence, but recently opened its doors to one member of the public at a time for an exhibition centred around domesticity

By Anna Solomon Published

-

Studio Frith and Perfumer H celebrate a decade of collaboration

Studio Frith’s ten-year partnership with Perfumer H has shaped a brand world defined by care, craft and quiet poetry. Wallpaper* meets studio founder Frith Kerr and design director Claire Koster to find out how

By Ali Morris Published

-

Kris Van Assche after fashion: discover the designer’s new homeware collection for Serax

The ‘Josephine’ collection for Serax features vases and other glass vessels inspired by Van Assche’s grandmother’s home

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

Jessica Anne Woodley’s ‘joyfully imperfect’ furniture seeks your inner child

The designer is launching GliFfY, a furniture studio offering playful forms that reflect on her personal growth

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

20 emerging designers shine in our ‘Material Alchemists’ film

Wallpaper’s ‘Material Alchemists’ exhibition during Milan Design Week 2025 spotlighted 20 emerging designers with a passion for transforming matter – see it now in our short film

By Hugo Macdonald Published

-

Meet the Palestinian artist putting a candy-coloured twist on traditional glassmaking

Designer Lameice Abu Aker is bringing joy and optimism to a time-honoured craft

By Ifeoluwa Adedeji Published

-

Casa Sanlorenzo debuts in Venice as a new hub for contemporary art

The luxury yachting leader unveils a stunning new space in a palazzo restored by Piero Lissoni – where art, innovation, and sustainability come together

By Cristina Kiran Piotti Published

-

This 18th-century Puglian villa has been restored with contemporary touches

The updated stonemason's workshop is a haven of centuries-old brick and sophisticated made-in-Italy design

By Anna Solomon Published

-

Eleven great things to see at 3 Days of Design 2025

The scale and scope of 3 Days of Design has expanded dramatically since its inception 12 years ago. Here, we share our pick of standout exhibitions and events from the upcoming edition (18-20 June 2025)

By Ali Morris Published

-

Technogym’s new Pilates reformer blends peak performance with sleek design

The Technogym Reform is the latest addition to the company’s design-led equipment roster, made from sustainable materials including apple-skin leather

By Tianna Williams Published

-

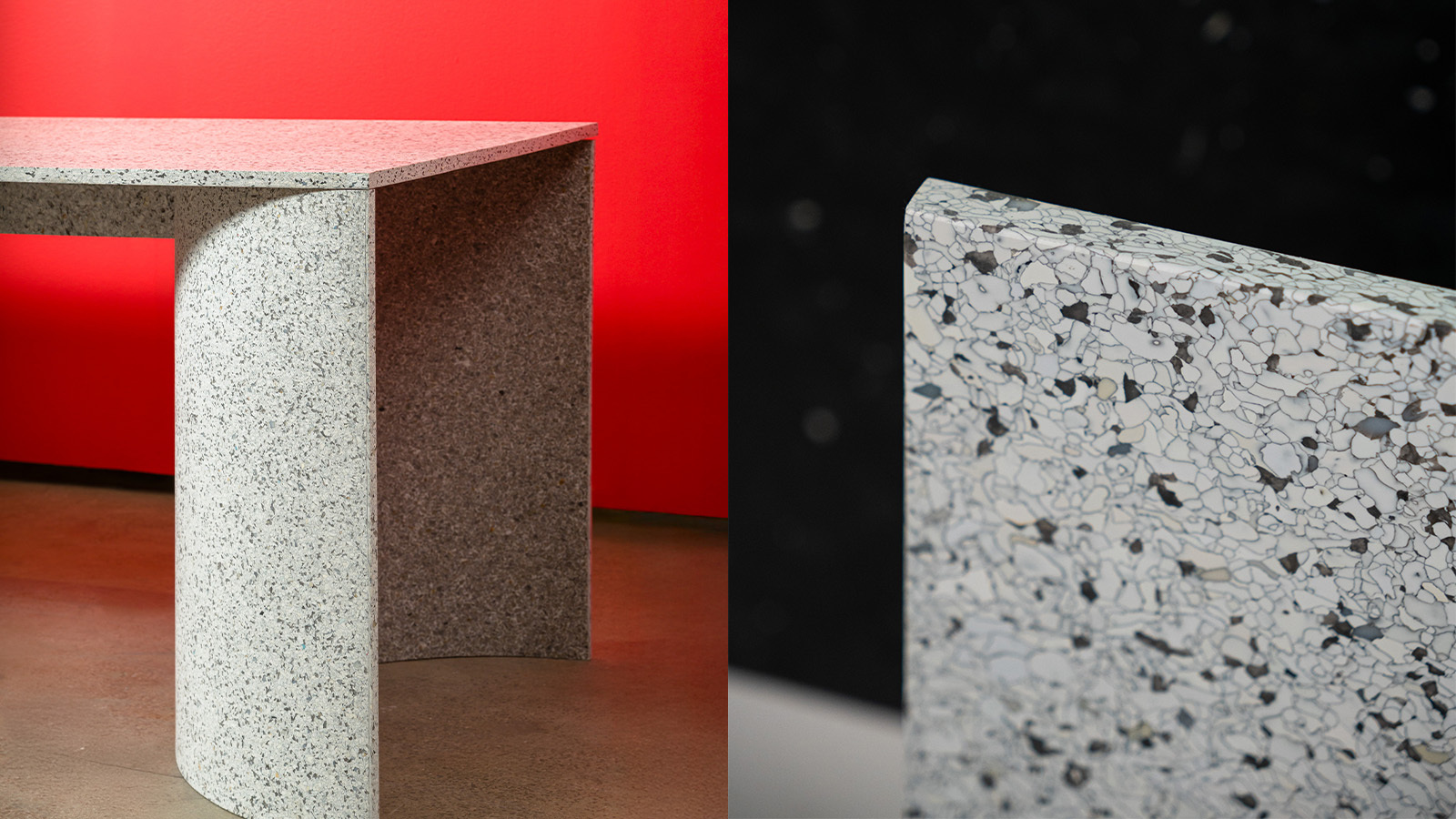

Vestre’s neo-brutalist furniture will bring ‘a little madness’ to Paris Fashion Week

Bound for Paris Men’s Fashion Week this month, Norwegian furniture brand Vestre reveals a sculptural bench and mirror created with designer Vincent Laine and fashion creative Willy Cartier – the latest outcome of its risk-taking ‘a little madness’ initiative

By Ali Morris Published

-

A love letter to the hammock

Looking to simplify the act of relaxing? Then consider a hammock

By Hugo Macdonald Published

-

Vincent Van Duysen launches ‘most modern’ Zara Home collection

The fourth instalment of architect Vincent Van Duysen’s collaboration with Zara Home introduces a modernist sensibility, with new materials and refined, architectural forms

By Ali Morris Published