Chanel launches Métiers d’art Prize in Hyères

Chanel has been a major partner of the International Festival of Fashion, Photography and Fashion Accessories in Hyères since 2014. This year, it has announced a new and exciting level of support for the cutting-edge festival, by introducing the Prix des Métiers d’art, an award given to one of ten competing fashion designers for their collaboration with the ten houses belonging to Chanel’s Métiers d’art: Desrues, Ateliers de Verneuil-en- Halatte, Lemarié, Maison Michel, Massaro, Lesage, Goossens, Atelier Montex, Causse and Lognon. In celebration of the launch of the prize, here we revisit our exploration of Chanel’s renowned artisan workshops, first featured in the March 2019 issue of Wallpaper* (W*240)...

Chirs Brooks - Photography

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

It was mid-December, a week after Chanel’s Egyptian-themed Métiers d’Art show in New York, and the artisan workshops were already back at full speed, preparing for the couture shows in January. In ateliers around Paris and beyond, people toiled in silent concentration, repeating the same gestures on feathers or buttons or fabrics or beads that their predecessors practised for generations, striving to create objects of wonder and surprise.

Paris once counted thousands of these workshops, crafting embroidery, hats, gloves, shoes, jewels and more by hand. Only a few have stood the test of time. Coco Chanel collaborated regularly with several of them, and when Karl Lagerfeld arrived at Chanel in 1983, he strengthened the connection.

Since then, the house has acquired 26 métiers d’art workshops, run by a subsidiary called Paraffection. Most are French, though they include a cashmere specialist in Scotland and a leather tannery in Spain. ‘Chanel would never have been what it is without them,’ says the house’s fashion president, Bruno Pavlovsky. ‘They are part of the DNA of the brand and one of our strongest assets.’ He explains that many of their acquisitions were financially sound, yet unsure about the future, especially those that lacked a succession plan. By picking up the workshops it considers indispensable, Chanel ensures their future and its own. Together, Pavlovsky says, they are building a ‘strong, supportive creative process’. So while other houses invest in crocodile farms, Chanel turns to Atelier Montex to create ‘python’ from embroidered paillettes that’s even more precious than the real thing.

Maison Massaro: shoemaker, Aubervilliers – established 1894

Left, the maison’s archives are filled with its clients’ bespoke wooden lasts. Right, two recent iterations of the classic two-tone sandal. Right, two recent iterations of the classic two-tone sandal developed by Maison Massaro for its first collaboration with Chanel in 1957.

To highlight the skills of these various artisans – or petites mains – Chanel presented its first Métiers d’Art collection in 2002. It is considered ready-to-wear, though many looks approach couture. Now one of the house’s fastest-growing collections, the Métiers d’Art show walks the runway in a different city every year.

The workshops are also growing, and actively hiring. And many of the artisans are under the age of 30. In order to keep up, Chanel is erecting a 26,000 sq m Métiers d’Art flagship on the periphery of Paris. Designed by architect Rudy Ricciotti with a delicate curtain of concrete threads, it is due to open in 2020.

To continue coming up with astonishing creations, the workshops are embracing new technologies and combining them with time- honoured tools and methods – laser cutters alongside Lunéville hooks. Given the means to experiment, they are taking tweed to the next level with technical threads, and using lasers to modify the surface of silk.

‘New technologies help us to make materials we never could before,’ says Hubert Barrère, artistic director of the venerable embroiderer Maison Lesage, which has also branched out into sophisticated tweeds. ‘What’s interesting is creating a new aesthetic by mixing things that don’t normally go together.’ He gives the example of a piece of embroidery from a 2015 collection, tiny 3D- printed plastic squares covered with lace. It is one of many treasures in Lesage’s archives, the world’s largest collection of couture embroidery, with 75,000 samples dating back to the company’s beginnings in 1858.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘Our biggest challenge is to stay relevant,’ says Aska Yamashita, artistic director of embroiderer Atelier Montex, who created the spectacular beaded collar that Pharrell Williams wore in the latest Métiers d’Art show in New York. In 2014, Lagerfeld tested Atelier Montex’s ability to work with atypical materials by requesting concrete for a couture collection. Rising to the occasion, the Parisian workshop combined small concrete cubes with glittery bits of leather and embroidered concrete-and-crystal flowers.

The button and jewellery maker Desrues is constantly mixing contemporary techniques with traditional skills for new effects, and also continues to practise methods that have fallen out of style, such as pouring glass cabochons of the type Coco Chanel wore on her cuff bracelets, just in case [before his death in February this year] Lagerfeld decided to ask for them. A button can require up to ten different techniques, from casting metal to colouring resin, and Desrues’ atelier counts sculptors, engravers and chisellers among its staff.

Whether it is destined for the runway or the boutiques, every Chanel button and bijou at Desrues is crafted largely by hand, to the same high quality. Collections director Sylvain Peters says the workshop delivers about 10,000 to 15,000 buttons for each runway show, plus thousands more for the boutiques. Whatever Karl asked for, he notes, ‘I had no right to say “It’s not possible”.’

Desrues: costume jeweller, Plailly – established 1936

Left, a design featuring wheel-shaped medallions, made in collaboration with Luxottica, being assembled for Chanel’s 2019 Cruis collection, ’La Pausa’. Right, a silicone mould used to produce buttons and ornaments in series.

At the milliner Maison Michel, artisans steam rabbit felt and then deftly stretch it by hand over blocky wooden hat moulds in a variety of forms. Only two artisans know how to operate the rare old Weissman sewing machines, which allow them to sew straw with invisible stitches. These women use nothing but the instinct and intelligence in their hands to guide the straw and replicate the shape of each mould.

Every season, Maison Michel’s workshop comes up with new shapes; either original combinations of moulds or else brand new ones such as a beret with asymmetrical indents. Young artistic director Priscilla Royer, who has been at the hatmaker’s helm since 2015, says its vast archives – some 4,000 wooden blocks of di erent shapes and sizes – ‘give us enormous creative exibility’.

Founded as a feathermaker in 1880, Maison Lemarié is unique in that it brings together four different types of savoir-faire under one roof: feathers, flowers, couture (as in ruffles or smocking) and pleats. It often mixes them together, says general director Nadine Dufat. ‘When we present pleating in which we have inserted featherwork or flower petals, we are something other than just a pleater.’

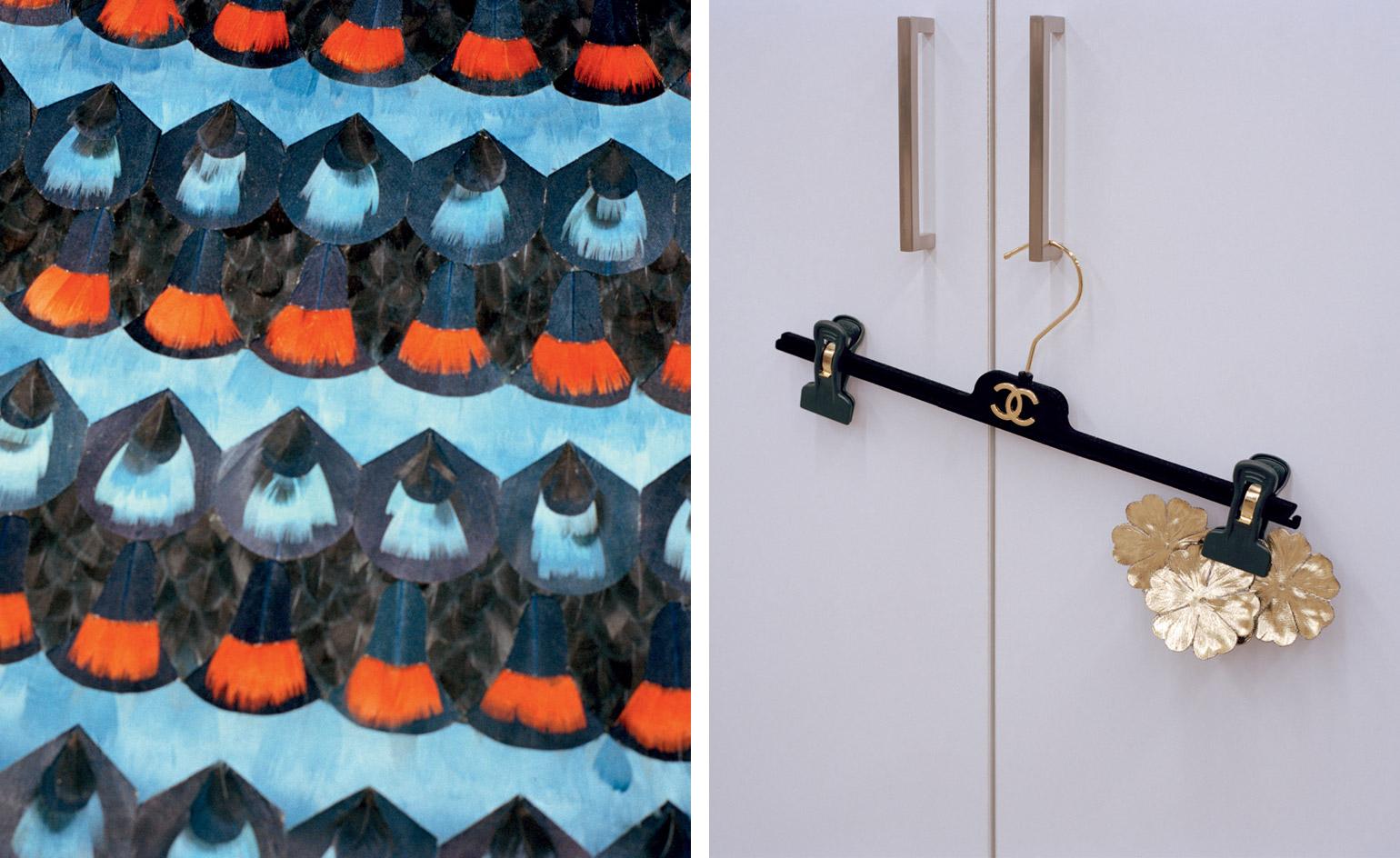

The Lemarié workshop produces around 60,000 of Chanel’s iconic camellias each year, using heated metal balls to shape petals from various materials. In another room, artisans hand-paint feathers and meticulously glue them into stunning patterns, such as the Ancient Egypt-inspired feather marquetry for a Métiers d’Art dress that required more than 1,000 hours of handiwork.

‘When you buy a luxury brand you’re buying a dream, but also a savoir-faire. Without the people behind that savoir-faire, there’s nothing.’ – Hubert Barrère

Maison Massaro, founded in 1894, was the bespoke bootmaker for Coco Chanel, inventing the slingback shoe whose elastic band allowed it to be discreetly slipped off underneath the dinner table. Today the Aubervilliers atelier owes its survival to Chanel, existing solely to create shoes for the collections. It also serves the house’s best customers, whose wooden shoe lasts hang in rows, inscribed with their names.

The reason for the workshop’s fragility, says artistic director Jean-Étienne Prach, is that it takes four people with different skills to properly make a bespoke pair of women’s shoes. (Men’s shoes are no walk in the park, either – the atelier can spend 20 hours stitching a single pair.) Simply put, the undertaking is not a cost-effective business, which is why Massaro is the last bootmaker of its kind in the world today. Nonetheless, the workshop is very much in demand and has a five-month wait for a fitting.

Pavlovsky emphasises that acquiring these ateliers was not a play to monopolise their skills. Though they maintain a privileged relationship with Chanel, they are encouraged to continue working for other designers – and most of them do. This ‘pushes them to be more agile,’ he says. ‘The more you work with different perspectives, the better you are.’ There was a time when couture houses forbade these ateliers to talk about their collaboration. Maison Lesage’s Barrère tells the story of how one day, atelier founder François Lesage entered Yves Saint Laurent’s couture house by the front door. Saint Laurent’s partner, Pierre Bergé, was standing at the top of the stairs and instructed Lesage to use the tradesmen’s entrance – l’entrée des fournisseurs.

Soon afterwards, Lesage had the idea for a book about the artisan workshops, titled Entrée des Fournisseurs. ‘The book got a lot of attention because it gave the métiers d’art their due,’ Barrère says. ‘When you buy a luxury brand you’re buying a dream, but also a savoir-faire. Without the people behind that savoir-faire, there’s nothing.’

As originally featured in the March 2019 issue of Wallpaper* (W*240)

Maison Lesage’s archives contain 75,000 samples, including this embroidery created for the 2017 Homo Faber exhibition in Venice, on which visitors could practice.

Maison Michel: hatmaker and milliner, Aubervilliers – established 1936. Left, one of the 4,000 wooden moulds in the maison’s archives. Right, rabbit felt is placed into a steaming cloche so it can then be stretched over a mould.

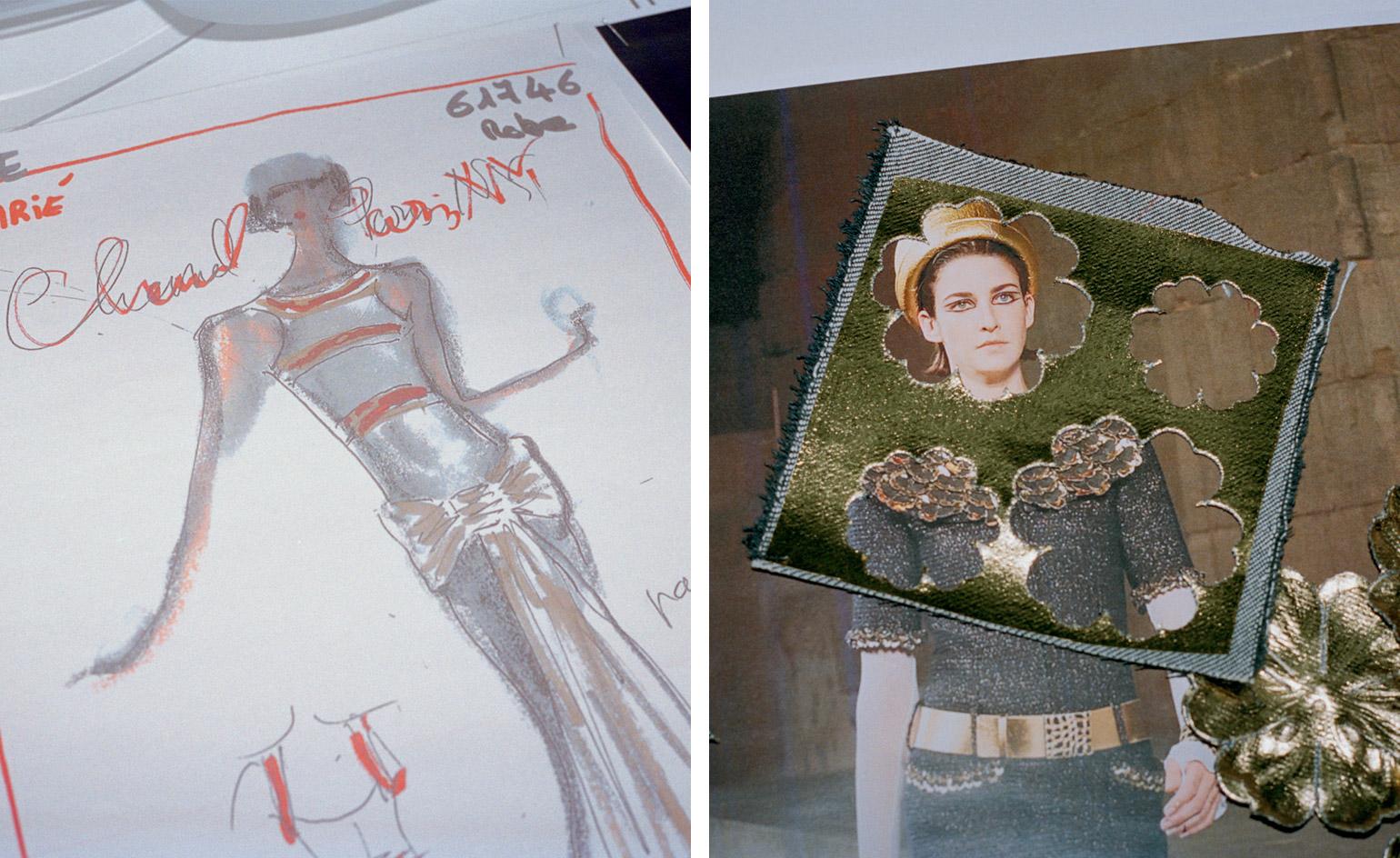

Maison Lemarié: feather and flower maker, Pantin – established 1880. Left, Lagerfeld’s sketch for a 2018/19 Métiers d’Art dress, with the embroidered area shown in red. Right, leather cut-outs waiting to be assembled into Chanel’s iconic camellias.

Left, a pattern made of hand-painted feathers for the 2018/19 Métiers d’Art collection. Right, leather cut-outs waiting to be assembled into Chanel’s iconic camellias.

INFORMATION

Amy Serafin, Wallpaper’s Paris editor, has 20 years of experience as a journalist and editor in print, online, television, and radio. She is editor in chief of Impact Journalism Day, and Solutions & Co, and former editor in chief of Where Paris. She has covered culture and the arts for The New York Times and National Public Radio, business and technology for Fortune and SmartPlanet, art, architecture and design for Wallpaper*, food and fashion for the Associated Press, and has also written about humanitarian issues for international organisations.