The pared-back designs of Mario Tsai

Mario Tsai – named by Nendo’s Oki Sato as a creative leader of the future for Wallpaper’s 25th Anniversary Issue ‘5x5’ project – talks about his experience working as a designer and entrepreneur in China, at the cusp of innovation and tradition

Xiaopeng Yuan - Photography

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

When Mario Tsai is not on the road for fairs or factory visits, he spends most of his time in his studio in a suburb of Hangzhou, just a two-hour drive south-west of Shanghai. ‘I found space and serenity here to do my work, while maintaining reasonable proximity to the city,’ he says. Tsai was born in Hubei, central China, and there was not much in his early years to suggest that he might become one of the country’s most promising designers. ‘I had a very simple countryside childhood,’ he recalls, ‘but I remember a scene on television of an architect walking down the road holding rolled blueprints; I was mesmerised.’

Mario Tsai on setting up a design practice in China

The ‘Grid’ bench, with Tsai’s dog BoJack in the background. Made using strips of 5mm-thick plywood, the bench was inspired by the processing of pixels in the formation of digital images

In the early 2010s, he says, the concept of ‘independent designers’ was virtually unknown in China, yet ‘there were a lot of furniture companies in Shenzhen and Dongguan serving the overheated real-estate market, and there was a great demand for novelty.’ His first job, after graduating from Beijing Forestry University’s College of Materials Science and Technology, was at one of those enormous enterprises churning out furniture for the mass property market; but instead of designing, he was tasked with engineering the products and their corresponding manufacturing processes, and with producing technical drawings so detailed and lucid that all factory workers, trained or not, could make sense of them. He did not appreciate quite how formative this experience would be to his future career until he set up his own studio in 2014.

It didn’t take Tsai long to carve out his niche. In 2015, he brought the studio’s first collection (including a prototype ‘Flying’ shelf, a metal shelf that played with basic shapes and the idea of balance) to Ambiente in Frankfurt, and the following year to Greenhouse, the emerging talents section at Stockholm Furniture & Light Fair, where he landed his first European clients. He has since worked with the likes of Shang Xia, Northern, Woud and Cedit. His best-known work, the 2018 ‘Insert’ table for Ferm Living, comprises a slender oval top supported by intersecting geometric forms (a coffee table option launched last autumn). To date, Tsai is still one of a select few Chinese designers who receive commissions from global furniture brands.

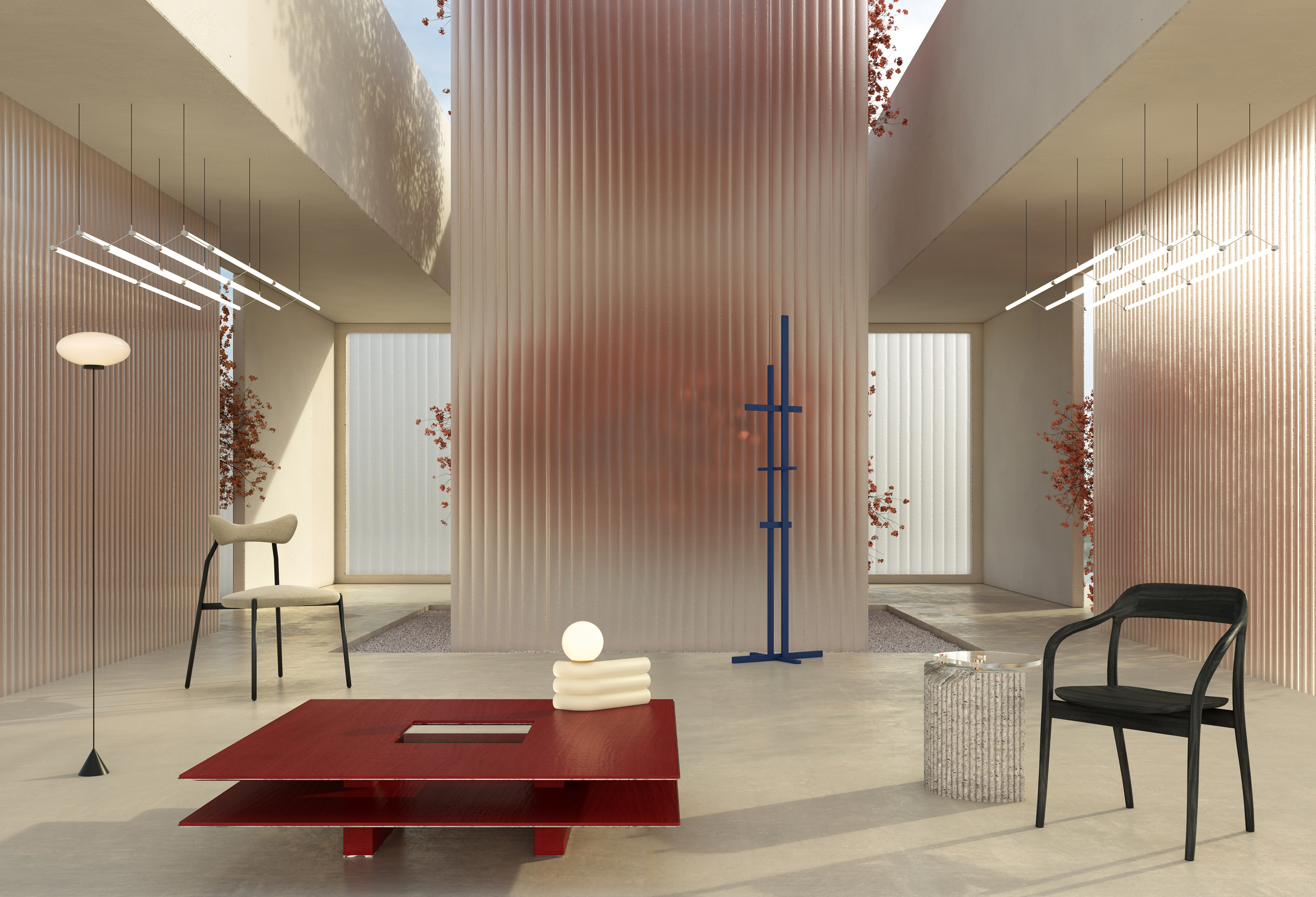

Various components for the ‘Mazha 3.0’ lighting system

Like most Chinese design studios in China, Tsai manages his own label and runs a direct-to-consumer business in the country’s burgeoning home decoration and furniture market (worth $740bn according to a 2018 study by Chinese financial news service Yicai).

Last year, he joined forces with Shenzhen Furniture Association, the organiser of Shenzhen Creative Week, to launch Designew, an initiative established to help build a more collaborative environment and amplify the value of design within the industry. Local designers from different professional backgrounds were paired with key manufacturers to trial creative partnerships.

An aluminium desk tray/paperweight from Tsai’s 2017 ‘Components’ series sits atop the ‘Rong’ shelf, also for Designew

Tsai himself teamed up with a producer of wooden furniture and created the ‘Rong’ collection. ‘This sector is highly industrialised, and its rigidity restrains innovation and quality,’ he says. The collection aims to break free from convention by creating structural parts that could be used across its pieces (for instance, table legs that could also be used for the shelf and bench) and by combining functions (a chair that doubles as a side table). Designew’s second edition, launched in March this year, drew eight manufacturers and 15 designers to further its goal of ‘identifying talents, nurturing skills and building brands’.

Mario Tsai and contemporary Chinese design

A pen rest from the ‘Components’ series is displayed on a ‘Grid’ bench

If we struggle to find traces of typical ‘Chineseness’ in Tsai’s work, perhaps we should be asking what we expect from contemporary Chinese design. ‘Since the economic reform of 1978, China has been a strictly modern society,’ says Tsai. ‘The culture that we live in today is a synthesis of foreign influences, remnants of tradition, and local wisdom.’ The general perception of traditional Chinese culture actually borrows from different historic periods. But the new generation of designers, especially those born after the 1980s, do not necessarily carry this cultural baggage. ‘As Chinese designers, what we create reflects different aspects of modern China – be it the technological advancement or social landscape,’ says Tsai. ‘My experience defines me, and my identity comes through in my design.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

RELATED STORY

His ‘Mazha’ lighting system was derived from the eponymous cross-legged folding stool (first recorded in the 1st century) that still adorns street corners today. The stool’s simple folding mechanism became the system’s backbone. Tsai wanted precisely three components in the equation – LED lighting tubes, metal poles and wire – to constitute an infinitely modular system. ‘My time spent at factories taught me how to execute ideas with the least amount of material and energy consumption to achieve maximal results,’ he says.

As Chinese designers, what we create reflects different aspects of modern China – be it the technological advancement or social landscape

Mario Tsai

His belief in stripping off anything unnecessary in a design led to him being identified as a minimalist: ‘I would not label myself as such, but this final touch makes almost all of my work look clean and intuitive,’ he explains. Clear structure also means longevity and low maintenance – components of the intricate system can be replaced individually and reconfigured easily – which contributes to its sustainable qualities.

Cut by axe then burnt, Tsai’s ‘Origin’ bench is part of a collection for Designew, conceived as a reflection on primitive tools

The starting point for most of Tsai’s work is research into the nuances of materials and technology, and how they can be adapted to more efficient production methods. This approach is apparent in the ‘Press’ and ‘Gongzheng’ tables, respectively constructed by bending sheets of steel and interlocking aluminium panels that can be extended indefinitely. His ‘Grid’ bench mimics image pixellation with 5mm-thick plywood sheets, while ‘Electricity Light’, which was to be launched at Milan Design Week in 2020, creates an optical illusion of an electric current flowing mid-air.

My time spent working at factories taught me how to execute ideas with the least amount of material to achieve maximal results

Mario Tsai

It uses new ultra-thin COB LED strips, which Tsai believes will stimulate new thinking in lighting design. Yet for one of his latest projects, Tsai has turned away from modern technology to explore the most primitive means of production, using only fire and an axe to create the ‘Origin’ collection. Imperfect wood, reclaimed from factories, was carved into approximate shapes before being set on fire. The resulting designs are unpredictable, with any mistakes in the process eventually adding to the uniqueness of each piece.

Nendo co-founder Oki Sato recently championed Tsai as one of 25 creative leaders of the future, for Wallpaper’s 25th anniversary ‘5x5’ project. He is, says Sato, ‘a designer who seems to go back to the “roots”, such as the process of making things, the principles of nature, and the laws of physics. It is like a scrap and build process with a completely different methodology. He has already been active across various fields, but I would love to see his architecture work some day.’

We’ll watch this space. Meanwhile, with international travel still largely stalled or impractical, Tsai has been looking closer to home for opportunities to present his work. ‘I am thinking of taking the team to the Gobi Desert,’ the designer says, ‘to make a short film or even a virtual exhibition, to experience and seek inspiration from its extreme austerity and primeval simplicity.’ We look forward to the results.

INFORMATION

Yoko Choy is the China editor at Wallpaper* magazine, where she has contributed for over a decade. Her work has also been featured in numerous Chinese and international publications. As a creative and communications consultant, Yoko has worked with renowned institutions such as Art Basel and Beijing Design Week, as well as brands such as Hermès and Assouline. With dual bases in Hong Kong and Amsterdam, Yoko is an active participant in design awards judging panels and conferences, where she shares her mission of promoting cross-cultural exchange and translating insights from both the Eastern and Western worlds into a common creative language. Yoko is currently working on several exciting projects, including a sustainable lifestyle concept and a book on Chinese contemporary design.