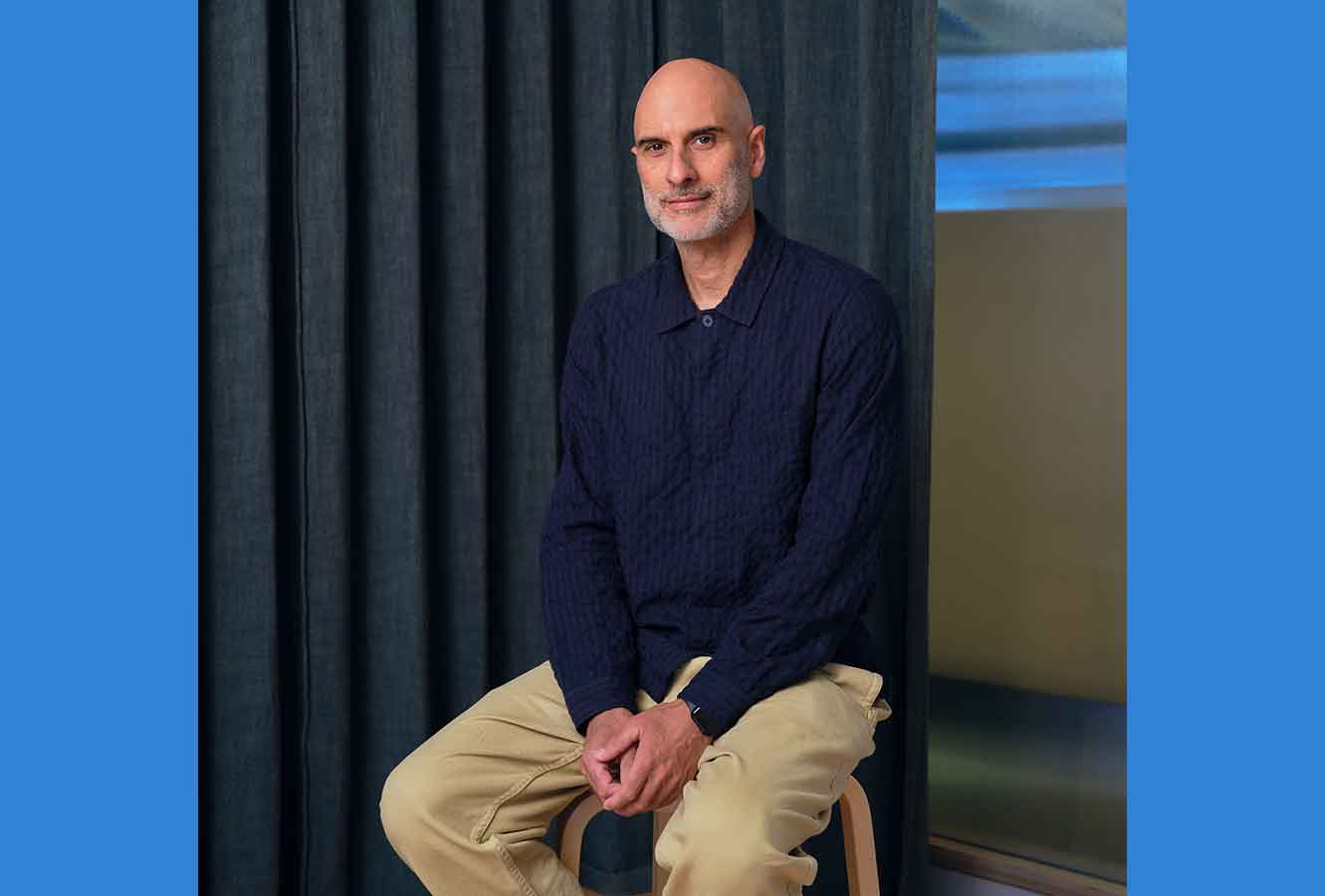

Paul Gulati on storytelling, multi-sensory design and the evolution of Universal Design Studio

'If a space works – not just as a beautiful image, but for the people using it – then we’ve done our job,' he tells us

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Founded by Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby in 2001, Universal Design Studio has long been a benchmark for thoughtful, high-quality spatial design. Over the years, its output has expanded from commercial interiors into exhibitions, cultural projects and large-scale workspaces – all underpinned by a meticulous approach to craft and storytelling.

As 'Feel the Sound', an immersive exhibition designed by the studio, comes to a close at the Barbican Centre (you can catch it until 31), we caught up with Universal Design Studio Director Paul Gulati – who has been with the practice for two decades – to reflect on the studio’s evolution, the role of sensory experience in design and what might come next.

Stella McCartney’s retail spaces were the first significant projects undertaken by Universal Design Studio following its launch in 2001

Wallpaper*: Can you tell us a bit about your background and how you came to join Universal Design Studio?

Paul Gulati: I studied architecture because I wanted to do something creative – I was always obsessed with drawing and mark-making. At the same time, I was releasing music on Aphex Twin’s label, Rephlex, in the 1990s, and I still have a sound studio. That exploration of sound has come full circle with our 'Feel the Sound' exhibition.

I initially set up my own studio, but began freelancing with Universal in the early 2000s – around 2004 or 2005. I was really drawn to the culture and craft of the studio. I’d seen the Stella McCartney project and was so impressed by the level of detail. I just wanted to be part of that. The passion for doing work to the highest standard was really addictive – and that’s why I’m still here.

Universal Design Studio's first foray into exhibition design was with 'Cold War Modern' at the V&A, marking the start of the studio's expansion from retail to cultural projects

W*: How has the studio changed in the two decades you’ve been there?

PG: It’s evolved a lot. Back when I joined, we were all based in one building in Shoreditch – Universal, Map, and Barber Osgerby. It felt like a design campus. Now we’re more spread out, and that reflects how the practice has grown. Edward and Jay always intended to build something that could evolve without being completely reliant on them, and that spirit is still here.

We started with small retail projects – some luxury, some department stores – and then opportunities opened up in cultural work and hospitality. 'Cold War Modern' at the V&A was a key moment, and winning the Science Museum’s 'Information Age' pitch came from people being intrigued by how we told stories through retail design. That idea of bringing narrative and materiality together has led us into all sorts of sectors – often in ways that were partly deliberate, partly happy accidents.

Gulati comments that winning the pitch for the Science Museum’s 'Information Age' exhibition 'came out of people being intrigued by how we told stories through retail design'

W*: What’s your role now, and how does the studio’s collaborative model shape the way you work?

PG: I’m one of three directors on the Universal side, alongside Carly Sweeney and Jason Holley. Others have played big roles over the years too. The name 'Universal' really reflects how we work – it’s not about a single authored voice.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Aesthetics matter, of course – they need to resonate culturally and emotionally – but for us, they’re the result of deeper decisions about function, atmosphere and intent.

Paul Gulati

We try to leave ego at the door. For me, it’s about staying creatively involved, nurturing client relationships and helping develop the business. But none of us want to be detached from the design process. If a space works – not just as a beautiful image, but for the people using it – then we’ve done our job. That means being hands-on and giving the team agency. It’s a talented and diverse group, and quite a few came through academia – some were even students of ours.

There’s a kind of cohort mentality: a wide range of work, but a shared philosophy and commitment to quality that keeps it feeling cohesive.

Experimental exhibition and cultural projects often feed back into the studio's commercial work, such as the Jellicoe, a destination workspace in King’s Cross, London

W*: Is there a red thread that runs through Universal’s projects?

PG: Storytelling is key. Whether it’s a retail space, a workplace, or an exhibition you’re only in for an hour, we’re always thinking about how to elevate the experience through materials, detailing and the senses.

We design from the inside out – we don’t have separate architecture and interiors departments. It’s one team, with different backgrounds and perspectives, coming together to create something holistic.

Sound is often a secondary concern – or seen as a problem to solve. But we wanted to use it creatively.

Paul Gulati

Aesthetics matter, of course – they need to resonate culturally and emotionally – but for us, they’re the result of deeper decisions about function, atmosphere and intent. We’re not chasing a signature style. It’s about crafting something meaningful for the people using it.

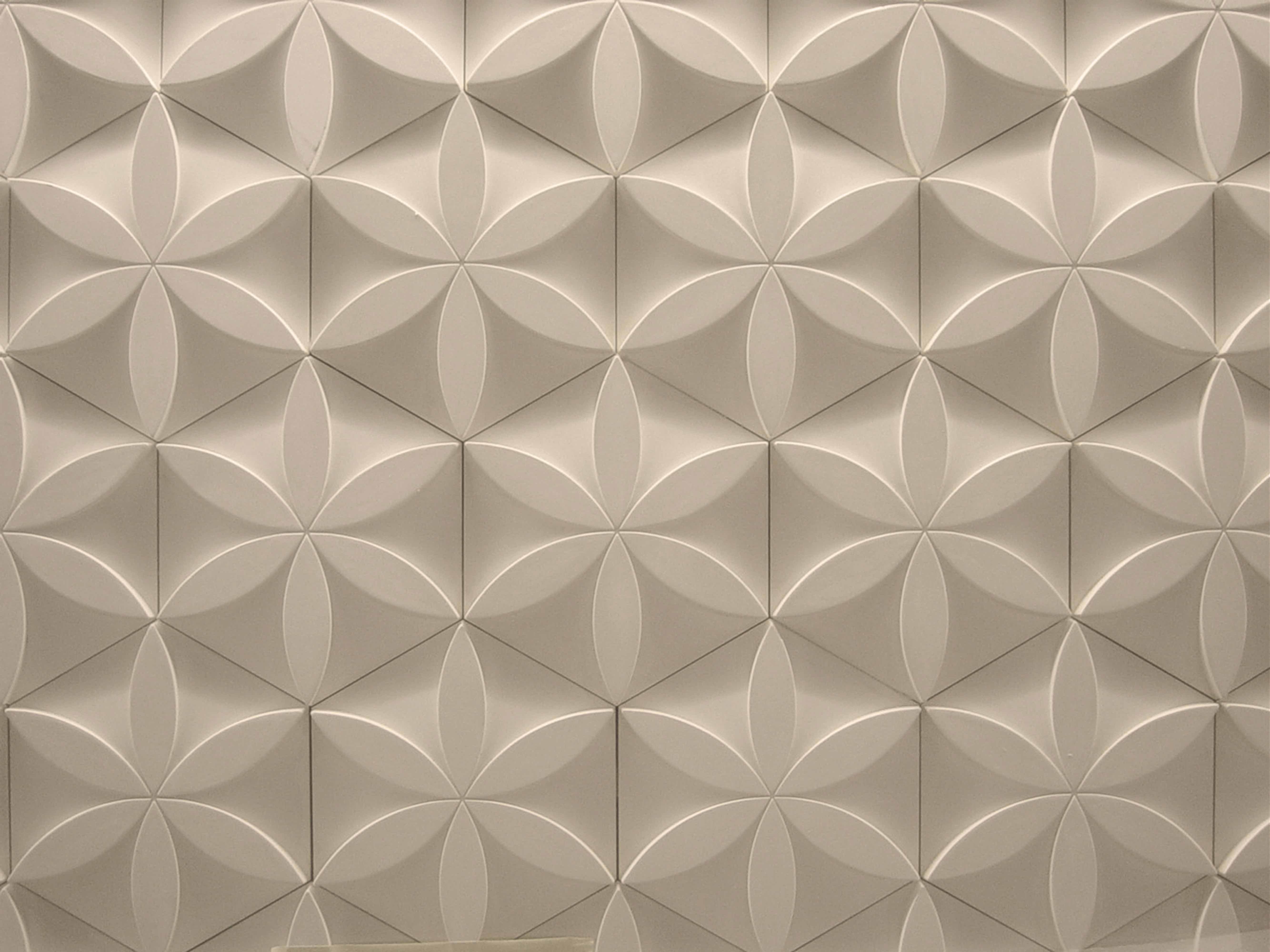

'Feel the Sound' is an immersive exhibition at the Barbican Centre, designed by Universal Design Studio, which explores how sound shapes our emotions, memories, and sense of self

W*: Tell us more about 'Feel the Sound' at the Barbican. How did that project come about?

PG: We’d worked with the Barbican Immersive team before on 'Our Time on Earth', which explored material stewardship and led us to research natural and overlooked materials – some of which we ended up using in commercial projects like The Jellicoe.

'Feel the Sound' was originally pitched as a music show for 2025 and has been produced by Barbican Immersive, co-produced by MoN Takanawa: The Museum of Narratives, Tokyo, Japan. We wanted to challenge the idea that spatial design is primarily visual. Sound is often a secondary concern – or seen as a problem to solve. But we wanted to use it creatively.

'Feel the Sound' challenges the idea that spatial design is primarily visual

Instead of isolating installations in separate rooms, we designed an open route with sound-insulated transitions that use white noise to create a kind of auditory palette cleanse. It’s a spatial tactic that relies on sound, not just sight. If you don’t notice it – if the sound doesn’t clash – it’s working.

These kinds of projects are a chance to be more experimental. We invest the time to research and test new approaches and materials. The goal is to feed those learnings back into our commercial work. That circular relationship is really important to us.

Ali Morris is a UK-based editor, writer and creative consultant specialising in design, interiors and architecture. In her 16 years as a design writer, Ali has travelled the world, crafting articles about creative projects, products, places and people for titles such as Dezeen, Wallpaper* and Kinfolk.