Piece by piece: exploring the intricate history of chess set design

Think chess, and chances are a certain, generic set of images will come to mind: that of stout, rounded-headed little pawns; crenelated towers for the rooks; the split mitre of the bishop; horses' heads; the shallow crown of the powerful queen; and the globus cruciger of the most important – but weakest – piece, the king.

That common iteration is collectively known as the Staunton pattern, or the 'Jacques Staunton Set' (below). Designed in 1849 by one Nathaniel Cooke and manufactured by the London game-maker John Jaques, it has long since become the industry standard, codified by the World Chess Federation and ubiquitous around the globe.

The ubiquitous 'Jacques Staunton Set', designed in 1849

A new book uses the Jacques Staunton Set as a jumping off point, delving into the wider, richer world of chess set design – one informed by politics, social upheaval, folklore, contemporary movements in art and design and more. Edited by former New York Times chess columnist Dylan McClain and designed and published by Fuel, Master Works: Rare and Beautiful Chess Sets of the World runs a startlingly broad gamut, kicking of with the intricate, high quality 19th century Indian sets produced by craftsmen from the East India and working its way through abstract, florid, minimalist and macabre fields that are functional at worst and intricately beguiling at best.

Picking highlights is a genuinely arduous task, though some are more immediately appealing than others. Take the 18th century Chinese rat set – an extremely rare design with each piece reconstituted as a robed rodent, fashioned from Indian ivory. 'It is certainly one of the most unorthodox of all antique Chinese chess sets,' writes Jon Crumiller, 'though the subject matter is perhaps not surprising as the rat is the first of the 12 animals in the Chinese zodiac.'

Pieces from the Reynard the Fox set

Fancier still is a later European set depicting the fable of Reynard the Fox (above) – a story dug deep into European folk song and literature. The pieces are vivid, almost cartoonish, in their realisation featuring anthropomorphised bears, monkeys, cats, storks, hares and lions (with Reynard usually cast as the bishop).

Elsewhere, filigree-like intricacy abounds, not least in an early 19th century Kashmir bell set, lathe made and finely carved with draping bells and delicate flower motifs, and in the more figurative Asian examples from the 18th century (an 'Incomparable carved set', each piece depicting a military garden scene typical of Manchurian China, more than lives up to its name).

The full range of pieces from the 'Incomparable carved set'

Most appropriate to Wallpaper* is a slimmer selection of 20th century sets, beginning with Man Ray's heavyweight bronze-gilt and patinated pieces – broadly recognisable as the traditional tokens – and heading quickly down an abstract rabbit hole. Take Takaka Saito's featured works: the first, dubbed 'See-Saw Chess Set' (1988) refigures the board as a mass of moving planks on a central axis, shifting with each move and transforming, says Larry List, 'the traditional battlefield plain into a precipitous shifting 3D terrain'; the second, 'Linear Chess Set (Stab Schachspiel)' sees standard pieces laid out on a single row board with 64 squares in a line – still, the book insists, totally playable, though god knows how.

A wire chess set created in a Russian Gulag work camp

More interesting still are the Russian sets: from bent wire examples constructed in the Gulag work camps to a travel set created for space-bound cosmonauts – perfectly salient examples of chess' pervading cultural significance overcoming such adversities as zero-gravity and forced labour. Who ever said it was just a game?

Wallpaper* spoke to Fuel’s Stephen Sorrell to gain a little insight into the book’s conception, remit and just how they managed to whittle down a millennia’s worth of cultural history to one slim tome...

W*: Did anything in particular prompt the making of the book? What was it that drew Fuel to compile a publication on the topic? And where does it fit into the studio's remit?

Stephen Sorrell: The book was made in collaboration with Agon, owners of the rights to the World Chess Championship. We met Ilya Merenzon, the CEO of the company, a couple of years ago. He has a good knowledge of publishing and was a big fan of our books on Russian culture. We always thought it would be good to collaborate on a book together, and he suggested the idea of publishing a book on chess sets. Ilya was interested to see how we would approach the subject from an art and design perspective. We decided to systemise the photography using black and white backgrounds so that each set could be documented consistently creating a standardised repertoire of shots. This accentuated the differences between each of these remarkable sets, while allowing them to sit together within the book itself. To achieve this we constructed a portable photographic ’studio’ that we transported around the world.

Many of our books are about discovering collections and showing them in a way that appeals to a new audience. Our books are visually led with a focus on design. The chess sets pictured in this book are incredible pieces of art and design. You don’t need to be a chess fan to appreciate these works. The history and stories behind each set is equally important, as with all our books, the depth of the content is crucial. It’s the combination of great images and good stories that make a successful book.

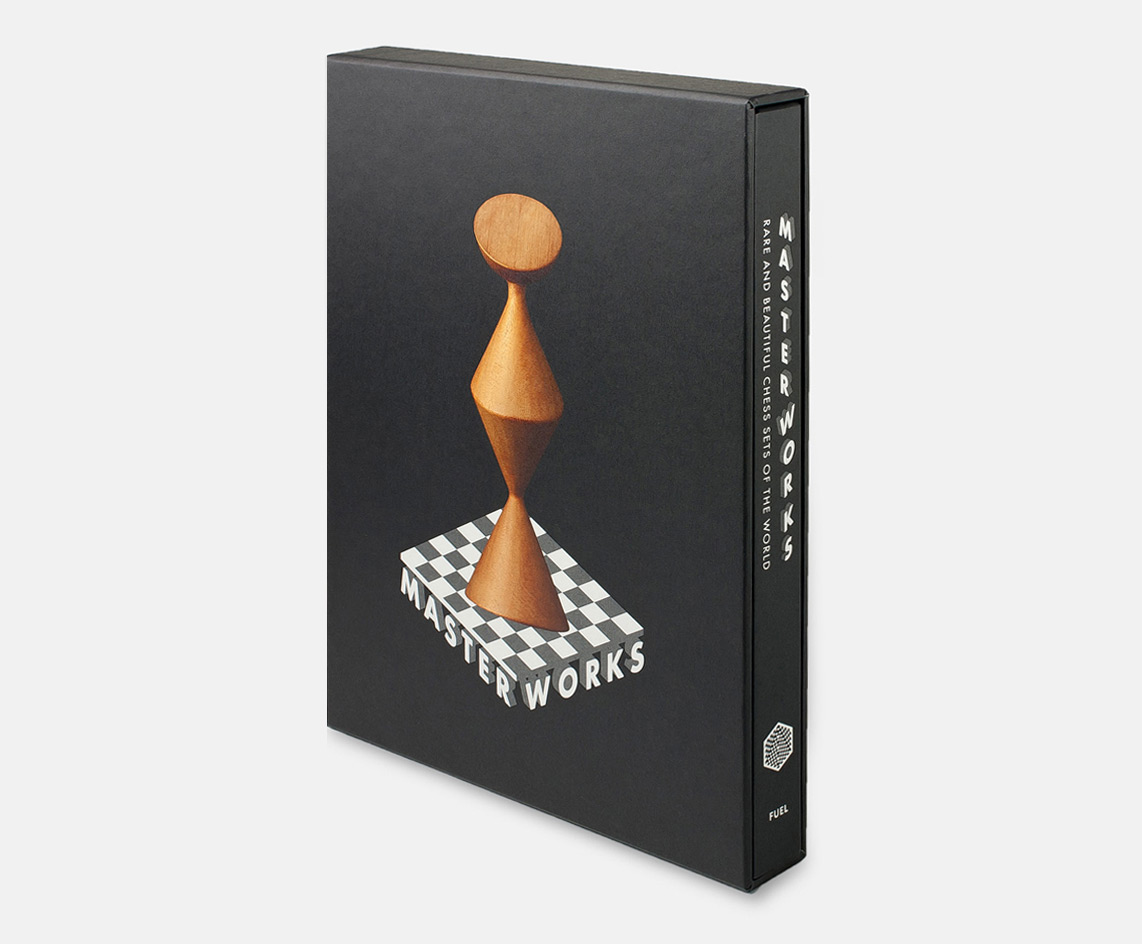

The 'Master Works' book, published by Fuel

Were there any notable sets that you ended up leaving out? Especially, given Wallpaper's remit, from the 20th century and onwards? We were bereft not to see Yayoi Kuama's pumpkin set in there.

It was important to show a range of sets through the ages - from early traditional sets, decorative sets and artistic interpretations through to sets made by Gulag prisoners. The final list was a joint decision with the editor Dylan McClean and we could only include a certain number. We were particularly keen on the Russian sets as there is some cross-over with our other books. While we wanted to make apparent the existence of artist chess sets and the continuing importance of chess for artists (hence the inclusion of Man Ray and Max Ernst), we were very aware that there was the potential for the book to be completely consumed by this motif. This could be the subject for an entire second volume…

What do you think the enduring appeal to designers (contemporary or otherwise) is in re-envisioning chess figures?

The fascination lies in the capacity they have to be modified and transformed, but still retain their essential function as chess sets. The designer has an incredible amount of freedom, while the audience is able to appreciate the creative and often abstract expression, the elementary requirements needed for a chess set to function remains.

Pieces from a Chinese rat set

Do you have any particular favourites from the book? And if so, why?

Our two favourites are both Russian. The ‘space’ set – the first to be played in orbit – is a masterpiece of design. It’s incredible that the Soviet space program thought chess was so important, so fundamental, that they assigned engineers to solve the problem of playing chess in zero gravity. Magnetic pieces could not be used as they could interfere with the systems on the spacecraft, so they came up with the ingenious solution of using ‘sprung’ pieces that work across a grid set into the board.

The Gulag set made from bent barbed wire is equally brilliant in its vernacular simplicity, displaying both an ingenuity of materials and the essential need for chess, but from a darker place in Soviet history. It is a stark contrast to the 1905 Fabergé set (also included in the book) reputed to be the most valuable in the world.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Takaka Saito's 'See-Saw Chess Set'

Takaka Saito's 'Linear Chess Set (Stab Schachspiel)'

An ingenious Russian travel chess set – to take into space

Examples of pieces from a 19th century Kashmir bell set

INFORMATION

Master Works: Rare and Beautiful Chess Sets of the World, £34.95 (limited edition £75), published by Fuel. For more information and ordering, visit the Master Works website and the Fuel website

Tom Howells is a London-based food journalist and editor. He’s written for Vogue, Waitrose Food, the Financial Times, The Fence, World of Interiors, Time Out and The Guardian, among others. His new book, An Opinionated Guide to London Wine, will be published by Hoxton Mini Press later this year.