How did the Shakers influence modern design? A new exhibition considers the progressive philosophy of the free church

‘The Shakers: A World in the Making’ positions the 18th-century sect as a pioneer of simple, functional and democratic design – principles that still guide aesthetics today

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

The Shakers: A World in the Making

On 7 June 2025, the Vitra Design Museum in Germany will launch ‘The Shakers: A World in the Making’, which will run until 28 September. The exhibition will explore the enduring influence of the Shakers, a Protestant sect that originated in England in the mid-1700s, its members emigrating to the American colonies in 1774.

‘The Shakers: A World in the Making’, with an exhibition design by Milan-based studio Formafantasma (a winner at Wallpaper's 2025 Design Awards), will bring together over 150 original Shaker artefacts, as well as newly commissioned works by contemporary artists and designers, creating a dialogue between history and modern creativity.

Dwellinghouse (1830), Hancock Shaker Village, Hancock, MA, 2024

One of the exhibition’s four sections, titled ‘I Don’t Want to be Remembered as a Chair’, argues that Shaker design should not be appreciated purely for its aesthetics but through the lens of the group’s religious and communal philosophy. Thus, ‘The Shakers: A World in the Making’ will examine how these values became a wellspring of inspiration for modern designers, and how the Shakers’ legacy continues to resonate in art and design today.

Today, ‘Shaker style’ has come to mean a number of things: design that is simple, minimalist and democratic; functional, practical and optimised; and that prioritises craftsmanship and, later, technology. Below, we explore how these principles are manifested in key 20th-century movements such as modernism and Bauhaus, which find their roots in the Shakers’ way of life.

How Shaker principles have informed modern design

Simplicity, minimalism and democratic design

The Shakers were, in many ways, ahead of their time, espousing egalitarian ideals and even institutionalising gender equality in the 1780s. These values extended to those with physical disabilities. The Shakers’ inclusive philosophy, explored in the exhibition through the work of artist Finnegan Shannon, was reflected in their architecture and design, which prioritised accessibility and simplicity – design for all, not just the elite.

This laid the groundwork for modernism, which emerged in the early 20th century as a reaction against the ornate styles of Victorian and art nouveau. Modernist designers preferred clean lines and rejected unnecessary decoration, intending for their work to be applicable across cultures and contexts. The likes of Le Corbusier, Alvar Aalto and Charles and Ray Eames admired Shaker principles.

Polishing broom, New Lebanon, NY, 2024

Oval box on a workbench, New Lebanon, NY, 2024

Bauhaus, which emerged in 1919, adopted similar ideals, with its clean lines and geometric shapes, avoiding ornamentation. Scandinavian design, too, bears the hallmarks of Shaker design, with its uncluttered, streamlined look (think Danish designer Hans Wegner’s iconic ‘Wishbone’ chair, as seen in this Swiss chalet, which has distinct echoes of Shaker seating). It also follows democratic ideals, aiming to create high-quality design for the many, distilled in the business model of Swedish stalwart Ikea.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Functionality, practicality and spatial optimisation

The importance that the Shakers placed on labour translated into designs that were functional: think ladder-back chairs, straight-legged tables, built-in cupboards, and efficient storage solutions such as wall-mounted rails, boxes and baskets. The Shakers were early adopters of serial furniture production; in the exhibition, in the section titled ‘When We Find a Good Thing, We Stick To It’, audiences can see examples of standardised and customisable Shaker chairs.

This element of Shaker design can be felt in Bauhaus, where decorative elements were minimised unless they served a function, and Scandinavian design, which seeks to create beauty from utility. Modernism sought to create efficient spaces and objects for modern life; the idea underpinning the ‘Eames Molded Plywood Chair’, for example, was that every element served a purpose. Modernism’s layouts, meanwhile, often used an optimised grid system.

‘The Shakers: A World in the Making’ uses furniture such as cabinets, chests of drawers and sewing desks to illustrate the community’s instinct towards orderliness, as codified in their 1821 and 1845 Millennial Laws, a body of teachings covering a wide range of aspects of Shaker life, including behaviour, dress and even how to climb stairs.

Interior of the Brick Dwelling House, Hancock Shaker Village, Hancock, MA, 2024

Craftsmanship, natural materials and openness to technology

The Shakers had a strong work ethic, which also translated into a focus on craftsmanship. In ‘I Don’t Want to be Remembered as a Chair’, the Shaker belief in labour as a form of worship is reinterpreted by artist and designer Chris Halstrøm through a large-scale embroidered artwork where each stitch is represented as a prayer.

The group’s emphasis on handmade quality resonated with the Arts and Crafts movements which took off in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and valued natural materials, simple joinery and built-to-last construction. The idea is also felt in Scandinavian design, where quality is paramount; this movement also, like the Shakers, favours organic materials such as wood, leather, linen, and stone.

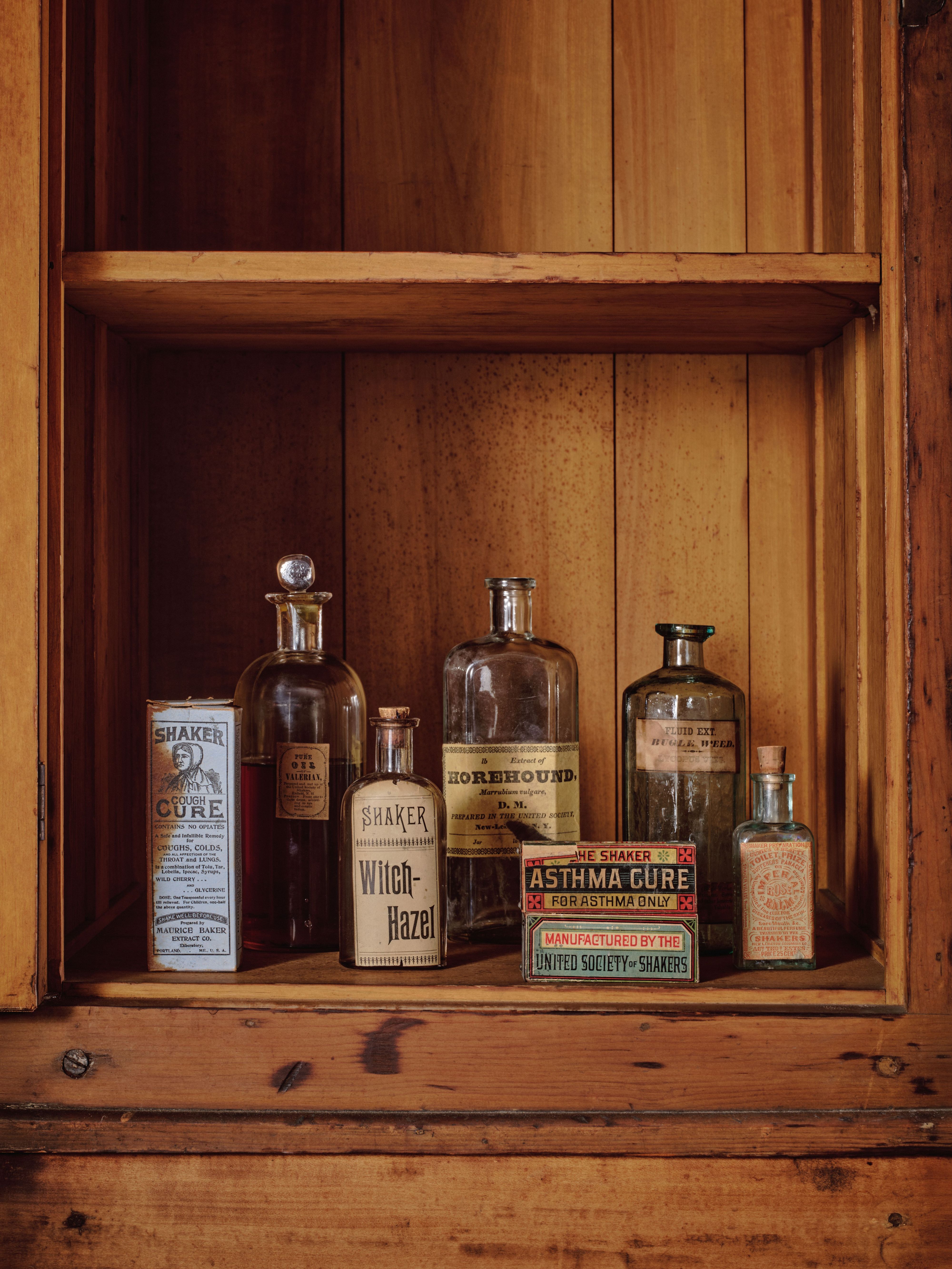

Various medicine bottles

Agricultural tools

Despite their insular communities, the Shakers were open to outside influences. The exhibition’s ‘Every Force Evolves a Form’ section traces how they interacted with the advancements of the wider world, showcasing oval boxes and rudimentary power tools. In ‘The Place Just Right’, audiences can see a radio that belonged to the Shaker community in Canterbury, Connecticut, as well as musical artefacts such as a metronome (music was a big part of Shaker life; they gained their moniker through the worshipful dance for which they were known). Shaker innovation is also explored through a commission from Christien Meindertsma, who reimagines their basketry as a biodegradable coffin.

Like the Shakers, later design movements such as modernism and Bauhaus embraced technological progress, especially industrial production, as a means of improving everyday life.

Full exhibition details at vitradesignmuseum.de

Anna Solomon is Wallpaper’s digital staff writer, working across all of Wallpaper.com’s core pillars. She has a special interest in interiors and curates the weekly spotlight series, The Inside Story. Before joining the team at the start of 2025, she was senior editor at Luxury London Magazine and Luxurylondon.co.uk, where she covered all things lifestyle.