Wallpaper* guest editor Tomás Saraceno talks science, spiders, and bouncing sounds off the moon

Science, technology, architecture and philosophy all find their way into the art of Tomás Saraceno. Whether in arachnid experiments or aerial cities, he has called for a radical transformation of our relationship with each other and the planet. Ahead of his largest exhibition to date, we visited Saraceno in Berlin to get entangled in his spider lab, dance in his theatre of shadows, and discover his plans to bounce sounds off the moon.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Sitting patiently on its massive web, a golden spider about the size of a man’s hand holds court in Tomás Saraceno’s studio. The web is attached to a frame, but – arachnophobes be warned – there is no glass case. A microphone amplifies vibrations travelling through the web (generated by the spider, its prey, or ecological interference), while a camera films particles of dust as they dance along to the vibrations, visitors’ breath or air currents.

From cosmic dust to sound waves, Saraceno is fascinated by what is in the air around us. Then again, there is little that doesn’t stir his curiosity: bubbles, the moon, dolphins – it all finds its way into his art. In his office, the book How the Hippies Saved Physics lies on a table near Naomi Klein’s book on climate change. Walking around his sprawling Berlin studio, Saraceno expresses his thoughts with infectious enthusiasm, veering from one barely finished sentence to another in an attempt to keep up with the activity of his brain.

As disparate as the elements of his work may appear, there is an underlying theme: to ‘learn how to see reality otherwise’, as the philosopher Michael Marder writes. Saraceno encourages us to take a fresh look at our presence in the world. How do we relate to our surroundings, how do we behave, how do we engage with one another and with other species?

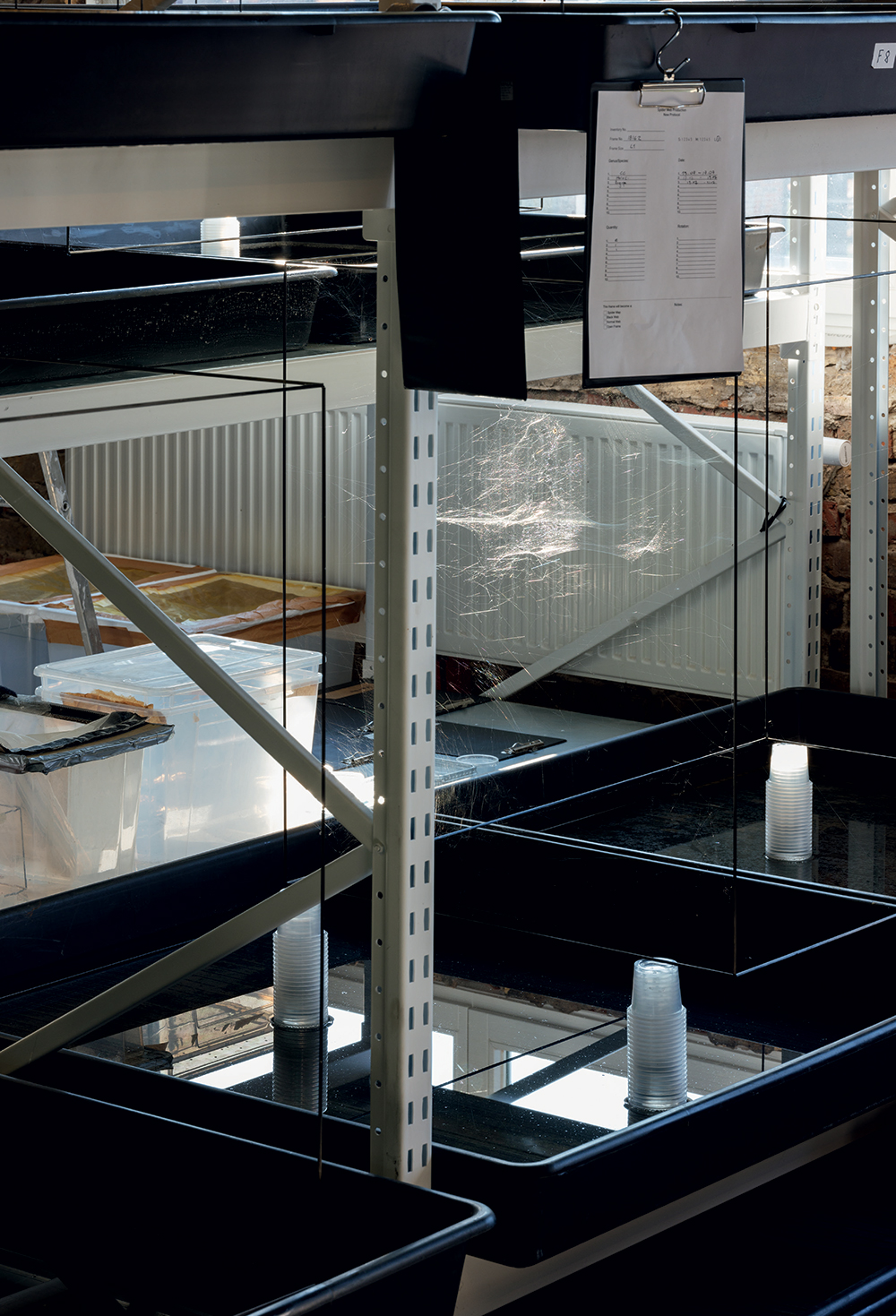

Inside the spider lab at Saraceno’s studio, the spider Nephila inaurata prepares to build an orb web.

His approach calls upon science, technology, architecture and philosophy to develop his art. Partners in his ongoing research have included the Max Planck Institute, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the Natural History Museum in London. In 2009 he was the sole artist among 120 engineers at Nasa’s International Space Studies Program. He explains that in urgent times ‘we have to lose the comfort zones of our silos and rethink the world together’.

Every artist is singular, but Saraceno might be particularly so. His CV reads that he ‘lives and works in and beyond the planet Earth’, He imagines living in floating cells, jamming with spiders, and nothing short of creating the next geological era. Marder puts him into the category of ‘thinker-artist’. Jean de Loisy, president of the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, says there are about ten artists in the world who push the boundaries of their field to such an extent: ‘What makes him an artist is that his belief system ends up as actual things.’

This autumn, Saraceno has taken over the entire Palais de Tokyo with a solo show titled ‘On Air’, his largest project to date. ‘I have rarely seen an audience for his work that was not stupefied by the poetry,’ says de Loisy. ‘At first, simply marvelling before the beauty of nature, then understanding the meaning. What he proposes is not just poetic and moving; it is necessary.’ Born in 1973 in Argentina, Saraceno is from a family of scientists. When he was a baby, the family escaped the military dictatorship by moving to Italy, returning when he was 12. ‘I struggled as a kid to belong to a place, moving from one country to another,’ he says. ‘I thought that maybe we could belong, everybody, to something called Planet Earth.’

The spider lab is home to around 130 species, which take turns spinning webs within black carbon frames to create sculptures.

Saraceno obtained his master’s in architecture in Buenos Aires, but never intended to be a conventional architect. Encouraged by his teachers, he found his way to art, studying at the Städelschule in Frankfurt, then earning a master’s in art and architecture in Venice.

Tanya Bonakdar became his New York gallerist more than a decade ago. ‘He had a special energy and creativity that was instantly attractive and had the potential to develop in a number of different directions,’ she recalls. ‘His mind could not be confined by a white cube space.’ Saraceno’s first exhibition with her, in 2006, explored airborne habitats as a solution to overcrowding on Earth. He has further developed the concept with his Cloud Cities, floating architectural modules that join together in different configurations, which challenge our notions about freedom of movement and borders. In 2012, one of these aerial cities sprang up on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, inviting visitors to climb inside its mirrored steel and Plexiglas polyhedrons.

‘Over the years, collaborations with museums around the world have given him the platform to execute larger projects and to further the concepts that have been there since day one,’ says Bonakdar. ‘Each installation continues to be a step towards realising his ultimate vision of creating sustainable ways in which humans can inhabit and sense the environment.’

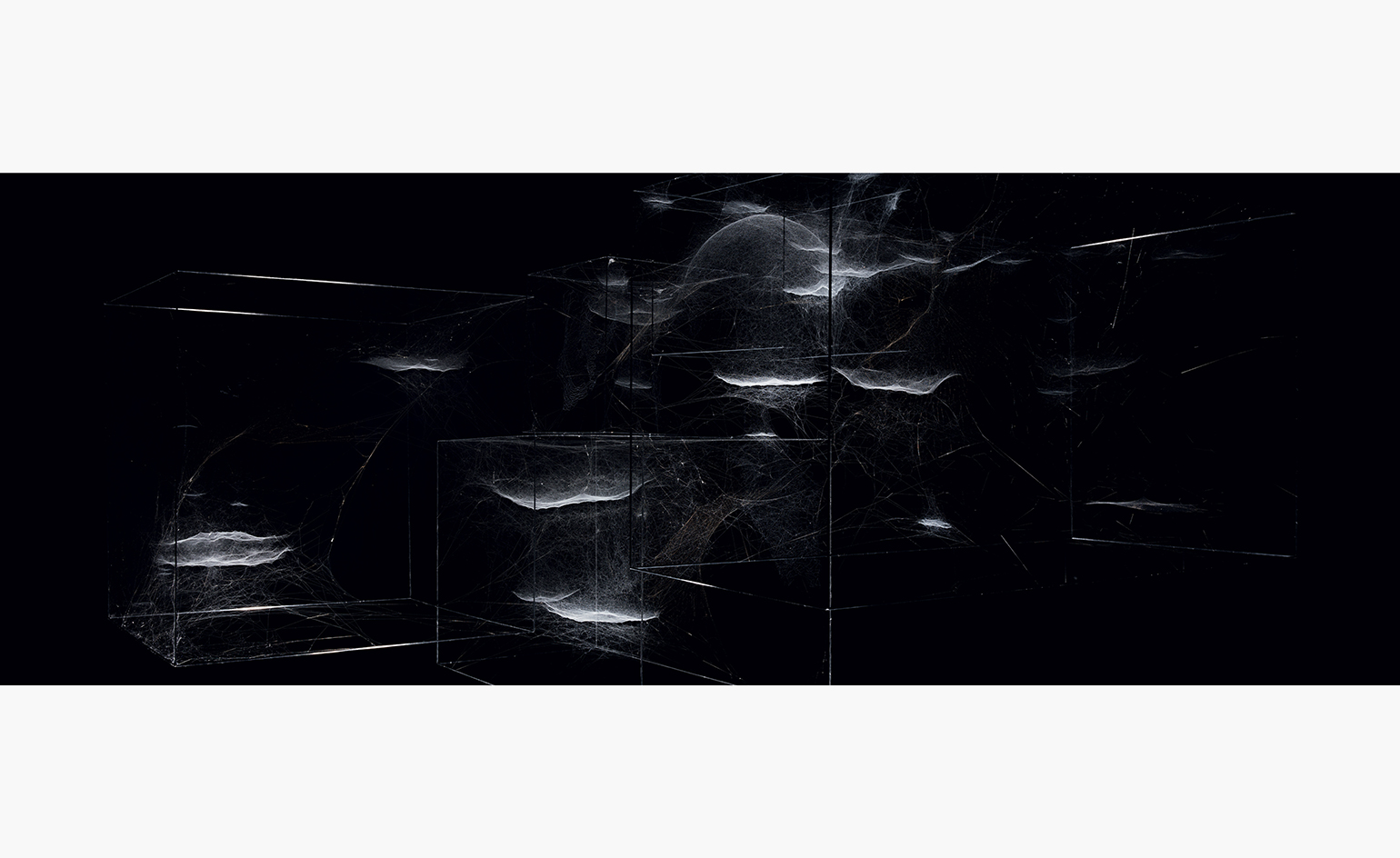

Saraceno mocked up his current Palais de Tokyo show in the storage facility next to his main studio. Seen here is one of the installations, A Thermodynamic Imaginary, seen here, a theatre of shadows that composes bodies of work throughout his career.

Spiderwebs are another of Saraceno’s fascinations. In 2009, the same year he received the Calder Prize, he presented Galaxy Forming Along Filaments, Like Droplets Along the Strands of a Spider’s Web at the Venice Biennale. An immersive installation made of elastic ropes, it examined the parallels between the structure of a web and the origins of the early universe. Working with researchers from Darmstadt’s Technical University, Saraceno developed a way to scan a spiderweb and reconstruct it in three dimensions on a human scale. He claims to own the only collection of (actual) webs in existence, some over a decade old. When people remark at how beautiful they are, he tells them they could have their own collection at home if they just stopped destroying them.

In 2016, Alex Jordan, a biologist at the Max Planck Institute of Ornithology, came upon Saraceno’s work while searching for information about spiderwebs. ‘No one was really looking in detail at the 3D complexity of the web, except for this artist,’ he says. Jordan reached out to him with a certain reserve, having worked with artists before and found the art-science divide too difficult to breach. But this time was different: ‘I found Tomás and his studio interested in scientific aspects in a way that could generate an actual transdisciplinary investigation.’ The two continue to meet whenever possible, sharing their thoughts about how the world we inhabit influences the ways in which we interact.

Saraceno’s Palais de Tokyo show weaves together various areas of research underpinning his practice. It includes a new work with around 90 carbon frames, where different species of spider have spun webs next to and intersecting one another. He speculates on how spiders with different degrees of sociability will relate: what does a spider do with a web that isn’t hers? What mode of communication will she establish? His team counted about 450 spiders living in the corners and shadows of the Palais, and he hopes that at least some of them are attending the show. What’s certain is that nobody is allowed to kill a single spider during it.

As mocked up in Saraceno’s studio, A Thermodynamic Imaginary immerses the visitor in a mobile geography shaped by ever-changing light conditions. Shadows enlarge and recede, consolidate and separate as they float around the monochrome space.

While preparing for the exhibition, Saraceno also contacted the renowned arachnologist Christine Rollard at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, who turned out to be a fan of his work. She immediately accepted the chance to work with him and contribute to a deeper understanding of creatures that are often feared and despised. Spiders, she says, are ‘exquisitely sensorial’, feeling and communicating through touch, scent and more. Saraceno wants to tune into what they have to say, and orchestrates ‘cosmic jam sessions’, using ultra-low frequencies to give aural form to the webs. ‘It’s very urgent to diversify the dialogue,’ he says. ‘We have the arrogance of thinking humans are the most successful species – and we keep decoupling from the rest of the world.’

He has invited three composers to make music with the spiders on different nights. One is Alvin Lucier, the 87-year-old American experimental music composer whose landmark work, I Am Sitting in a Room, explores the playback of sound in a particular space. Reached by telephone, Lucier laughed delightedly at his memory of meeting Saraceno: ‘He’s crazy and wonderful. He wants me to bounce sounds off the moon.’

Another new work is a vast entanglement of threads that meet up at various nodes. Each one can be plucked like a guitar string to transmit a natural or manmade sound – the moon, the sea, even fracking. Some sounds are live-streamed, others pre-recorded, and they are accompanied by vibrations in the floor. ‘Sometimes you touch and you don’t know who else you are touching, metaphorically,’ says Saraceno. ‘Do I have a consequence? Do I hear my actions or not?’

Saraceno intends for A Thermodynamic Imaginary, seen here in prototype, to dissolve the boundaries of the body, as visitors’ shadows merge into umbras and projections of aerial sculptures, pendent geometries, gathering clouds and transient soap bubbles.

Saraceno is a stubborn idealist. His most ambitious initiative, Aerocene, is an open-source community project that centres upon balloon-like sculptures that can transport human passengers through the air, similar to the spider’s method of releasing a thread and hitching a ride on wind currents. His accompanying Float Predictor is a journey planner that indicates the different wind trajectories that will get you to your destination over the next 16 days. ‘Today, when you book your ticket online, it will tell you what is the cheapest day,’ he says. ‘But for carbon sustainability it is not so good.’ What he proposes is wildly different – giving up control in a symbiotic relationship with the planet and the sun.

Is he for real? He says yes – but it doesn’t matter. If art can change the world, it’s by transforming the way we perceive and live in it. Saraceno urges us to accept the rhythms of forces more powerful than we are, and see ourselves as part of one great cosmic web.

As originally featured in Tomás Saraceno’s guest editor section in the October 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*235)

Different species have taken turns to weave hybrid webs within these frames, photographed in Saraceno’s studio. Saraceno is showing around 90 open frames at the Palais de Tokyo, and hopes the native spiders will continue to build on the structures.

INFORMATION

‘On Air’ is on view until 6 January 2019. For more information, visit the Palais de Tokyo website and the Studio Tomás Saraceno website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Amy Serafin, Wallpaper’s Paris editor, has 20 years of experience as a journalist and editor in print, online, television, and radio. She is editor in chief of Impact Journalism Day, and Solutions & Co, and former editor in chief of Where Paris. She has covered culture and the arts for The New York Times and National Public Radio, business and technology for Fortune and SmartPlanet, art, architecture and design for Wallpaper*, food and fashion for the Associated Press, and has also written about humanitarian issues for international organisations.