Patrick Caulfield exhibition at Tate Britain, London

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

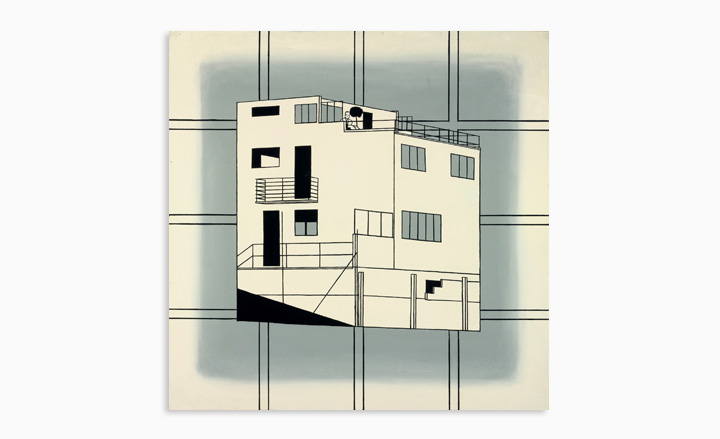

The late British artist Patrick Caulfield is, or rather was, in many ways at least, very Wallpaper*. He didn't just paint chairs, he painted chairs by Saarinen, Eames and Bertoia. Caulfield had taste. He was an architecture buff and fan of Le Corbusier and indeed the first of his works you see on entering Tate Britain's new Caulfield show features an early modernist villa in Czechoslovakia, painted in 1963.

'There's a little figure sitting in 'Concrete Villa, Brunn' which is a self-portrait,' Caulfield once said. 'That was really because I was in love with that architecture. I thought I would like to have a house just like that, with tubular steel and iron windows and concrete.' (Interestingly, the gallerist Robin Katz showed the painting at the 2011 PAD design fair in London, rather than a straight-ahead art fair, and got his asking price of £450,000.)

Caulfield studied at the RCA alongside David Hockney and was part of the New Generation exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1964, one of those rare shows that heralds not just new but lasting ideas. He was soon called a 'pop' artist - clearly, people said, covering some of the same ground as Richard Hamilton. Caulfield, though, always rejected the pop tag. He was not in love with, or even fascinated by, America, not in the way Hamilton, Blake and Hockney were. Nor by commercial imagery, certainly not in the way Lichtenstein and Warhol were.

'People were doing Pepsi Cola tins, girlie magazine images, American trucks, skyscrapers, whatever was up to date,' he said. 'I felt there was more scope in not choosing that kind of subject matter. It was coming mainly from American culture as far as I could see. I don't think that was really the sort of life one was leading. One wasn't leading the polished chrome, racy life that these images suggest.'

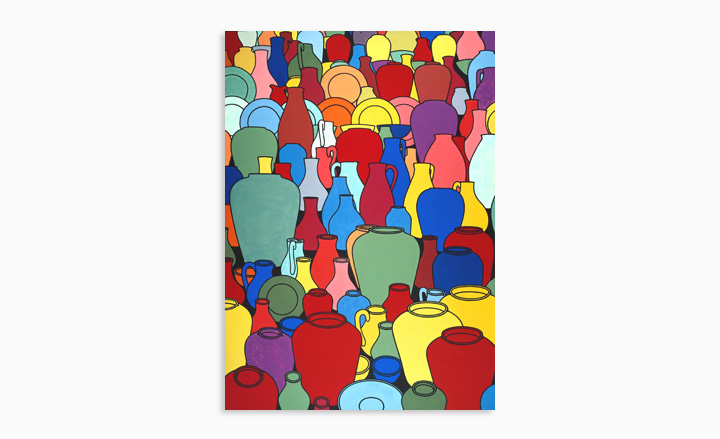

He had studied graphic design and had a clear appreciation of the sign-writer's art. He painted flat areas of colour on board using gloss paint, and used heavy black lines. But he was looking to Juan Gris and Matisse for inspiration, rather than advertising and comic books (though you do feel that, at any moment, Tin Tin and Snowy might burst through the famous massed urns of 1969's 'Pottery').

And his subject matter was domestic. Caulfield was an acute observer of post-Festival of Britain shifts in taste and ideas of sophistication, Conran's democratisation of good (Scandinavian) design and Elizabeth David's zealous advocacy of continental cooking. Moreover he did it with wit, an elegant, economic line and an incredible control of colour. And while he has some of Lichtenstein's ironic distance, coldness even, he was more celebrant than satirist.

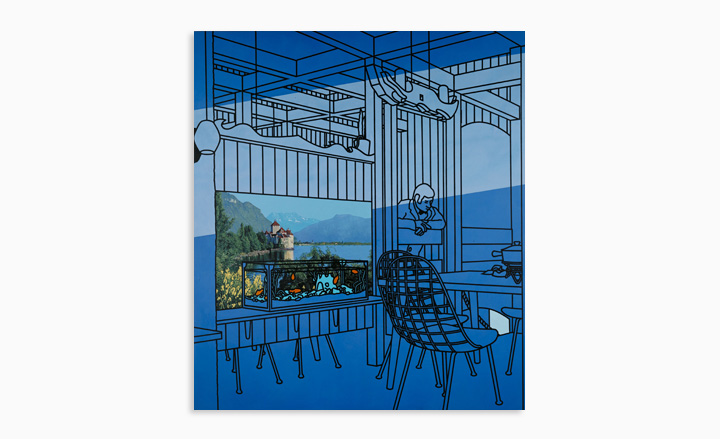

His interiors were often taken from vintage design books and magazines. And in 'Foyer', from 1973, loaned to Tate Britain by a certain David Bowie, there is a sense of wonder at the sudden cultural and culinary plenty (in certain parts) of a decade earlier and the late arrival of larger-scale modernism in Britain a decade before that. But there is also something of Edward Hopper's dreamy dislocation. These are pictures about what we might remember of a scene, what might remain vivid, what detail might be lost.

Tate Britain is selling the Caulfield show as a two-for-one deal with a complementary Gary Hume retrospective. Which makes sense. Hume is another master of colour and line (and fan of gloss paint).

'Foyer', 1973. Collection David Bowie.

'Cafe Interior: Private Afternoon', 1973. Private collection.

'Pottery', 1969. Courtesy of Tate.

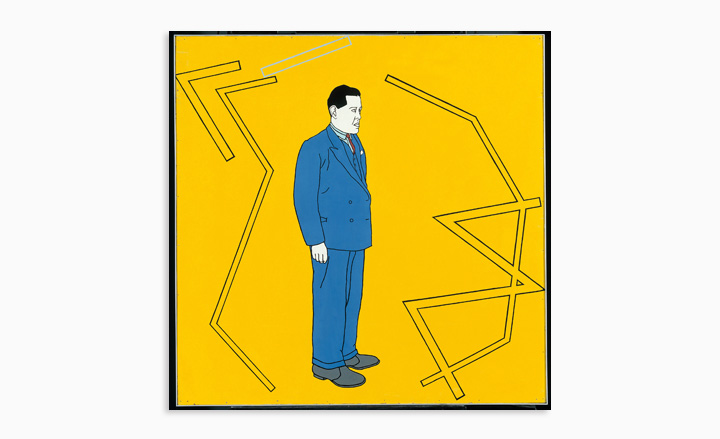

'Portrait of Juan Gris', 1963. Courtesy of the Pallant House Gallery, Chichester.

'Bishops', 2004. Private collection.

'Concrete Villa, Brunn', 1963. Private Collection.

'Hemingway Never Ate Here', 1999. Courtesy of Tate.

'After Lunch', 1975. Courtesy of Tate.

ADDRESS

Tate Britain

Millbank

London SW1P 4RG

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.