‘Women in Revolt!’ at Tate Britain is a deliciously angry tour de force of feminist art

‘Women in Revolt!’ puts feminist art from 1970 – 1990 under the spotlight at Tate Britain

Women are angry, and they are prolific – one of the surprises upon entering ‘Women in Revolt!’, a new exhibition at Tate Britain that puts feminist art from 1970 to 1990 under the lens, is its sheer scale and comprehensive coverage.

‘I think the mainstream art world is finally waking up to the fact that it's been following a very singular, patriarchal, colonial view of art history for a long time and that our audiences demand different perspectives,’ says curator Linsey Young. ‘This is the show I've wanted to make for the whole of my career but it's only in recent years that it has been seen as a viable exhibition to make it one that people will come to see. In terms of the wider political perspectives, there are some quite extraordinary (and depressing) parallels with the 1970s and 1980s.’

‘Women in Revolt!’: a survey of feminist art

Installation view of ‘Women in Revolt!’ at Tate Britain, 2023

Confronting these parallels upon entering the exhibition is a surprise. It’s a multi-sensory mish-mash, set to a frazzling aural pitch, from Gina Birch’s 3 Minute Scream, played on an endless loop, to that distinctive plaintive screaming of a newborn, designed to send your cortisol through the roof.

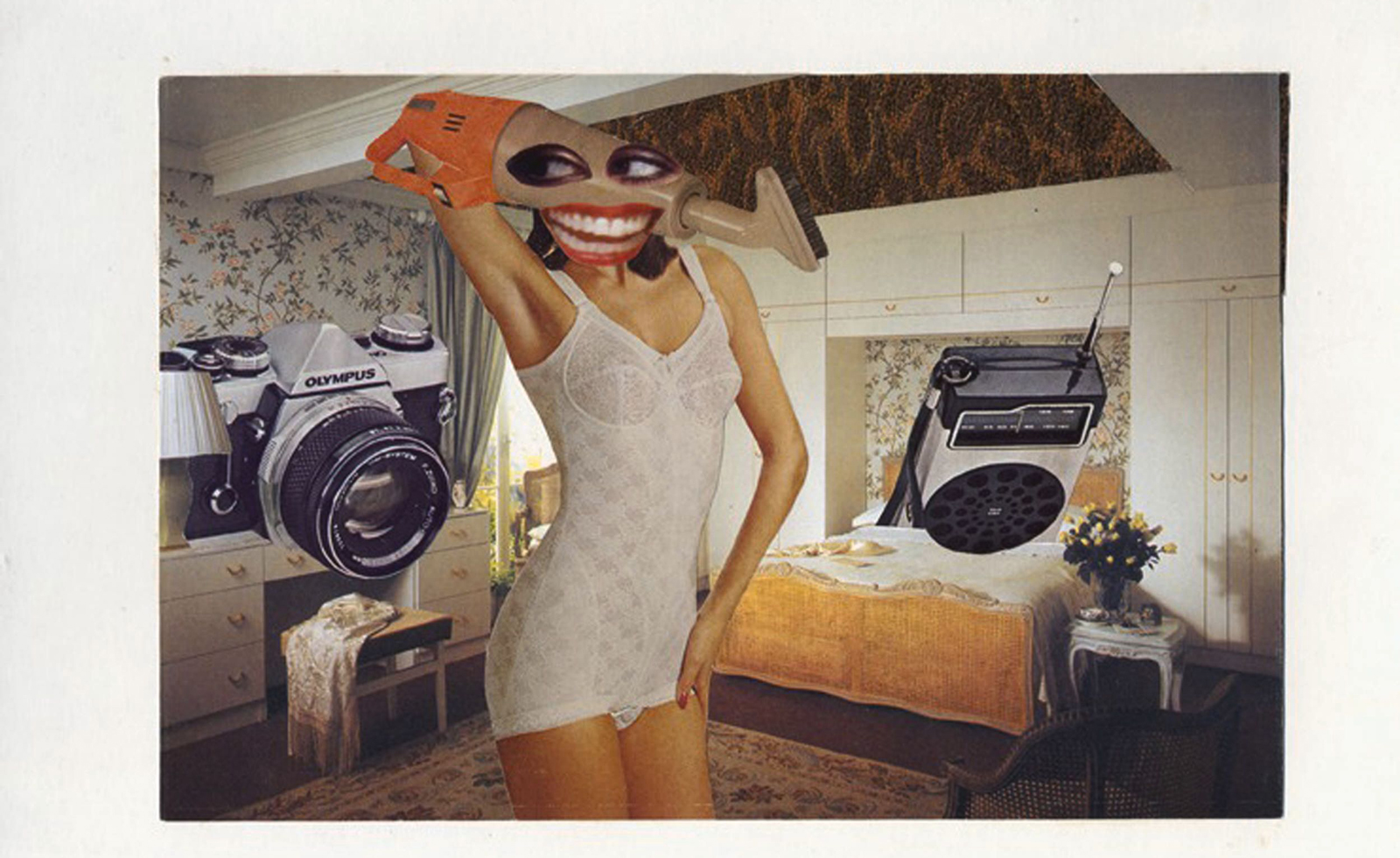

A group of over 100 women artists, living and working in the UK, are included here, from Sonia Boyce, Susan Hiller, Chila Kumari Singh Burman and Linder to Margaret Harrison, Penny Slinger and Monica Sjöö, whose paintings, drawings, textiles, sculptures, films and printmaking are placed in a social and political context.

Installation view of ‘Women in Revolt!’ at Tate Britain, 2023

‘There is an enormous swathe of British art history that really hasn't been acknowledged in mainstream galleries; artists, writers, smaller galleries and archives have championed this work for decades but it's really the first time you’ll see it in one place in a major institution,’ Young adds. ‘The other thing I really hope people respond to is that you don’t need to have had commercial success or have a massive exhibition history to be taken seriously. Women’s lives have so often been disrupted by caring responsibilities, badly paid jobs or people simply not listening to them, so they often don't have the same “profile” as male artists of the same generation. They also often weren't interested in that kind of success, so many of the women in this show are card-carrying socialists with little interest in the commercial art world.’

Domestic themes – lost in motherhood, the housework, the drudgery – join political stances, with photography and films from Marianne Elliott-Said (aka Poly Styrene) and The Neo Naturists taking a post-punk jab at the patriarchy. Movements, including the BLK Art Group and advocacy group and archive Panchayat, look at women’s role in British Black and South Asian artistic narratives. Artists’ response to Margaret Thatcher’s Section 28 – prohibiting the promotion of homosexuality – strikes an angry, emotional note, on which the exhibition closes.

Houria Niati, No to Torture (After Delacroix 'Women of Algiers') 1982-83

The role that print and graphic imagery play is celebrated here, in a boldly drawn subversion of traditional propaganda connotations. Feminist print-making collective See Red Women’s Workshop is featured heavily throughout, the graphic imagery it created between 1974 and 1990 neatly linking art and activism. Say the group’s members: ‘We understood that graphic imagery could subvert sexist stereotypes with immediacy and humour, and grab attention. Humour was always an important part of our work: we used the See Red Quizzical Eyebrow from the early years to reflect how we felt about the topic and to also to encourage women to question/challenge/get angry about what was happening. Bite the hand, YBA Wife and Right on, Jane were visually more direct and employ humour as consciousness-raising; all challenged the received ideas about political posters being aggressively functional and too serious, as well as challenging accusations that feminists are humourless.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘Women in Revolt!’, 8 November 2023 – 7 April 2024 at Tate Britain, London

tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/women-in-revolt

Gina Birch, still from Three Minute Scream, 1977. Courtesy the artist

Lubaina Himid, The Carrot Piece, 1985

Hannah Silver is a writer and editor with over 20 years of experience in journalism, spanning national newspapers and independent magazines. Currently Art, Culture, Watches & Jewellery Editor of Wallpaper*, she has overseen offbeat art trends and conducted in-depth profiles for print and digital, as well as writing and commissioning extensively across the worlds of culture and luxury since joining in 2019.