The darkness of photojournalist Don McCullin explored in Tate Britain retrospective

The iconic British war photographer reveals the personal toll his photographs have taken as a major survey spanning his six decade-long career opens in London

Sir Don McCullin - Photography

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

‘I grew up angry,’ says Sir Don McCullin, as a new retrospective of his work – including some of his earliest photographs – goes on show at Tate Britain. He was born in Finsbury Park, north London, in 1935, and spent his childhood sleeping in the same room as his brothers, his mother and his chronically ill father. ‘The way I grew up shaped my life, because I can understand poverty,’ he explains.

His father died when he was 14, forcing McCullin to drop out of school and bring money in for the family. ‘I was angry about that,’ he says today. He spent his teenage life out on the streets of north London, still in partial ruin after the Second World War Blitz, and peopled by homelessness. He got his first camera – a Rolleicord – while on national service with the RAF in North Africa. ‘I was bound to be angry,’ he notes when recalling the poverty, misery and pain he saw through the viewfinder of that camera. ‘It would be wrong if I wasn’t angry.’

McCullin is now 83, and has been photographing consistently for more than 60 years. His new exhibition features over 250 of his photographs over the span of his long career, each of which has been hand-printed by the photojournalist in his darkroom at his home in Somerset. The exhibition is entirely in monochrome. McCullin actively seeks out dark images, and will process them as such. ‘I see darkness as my voice,’ he adds. ‘I sometimes almost believe myself that I am speaking for the victims and the casualties of war.’

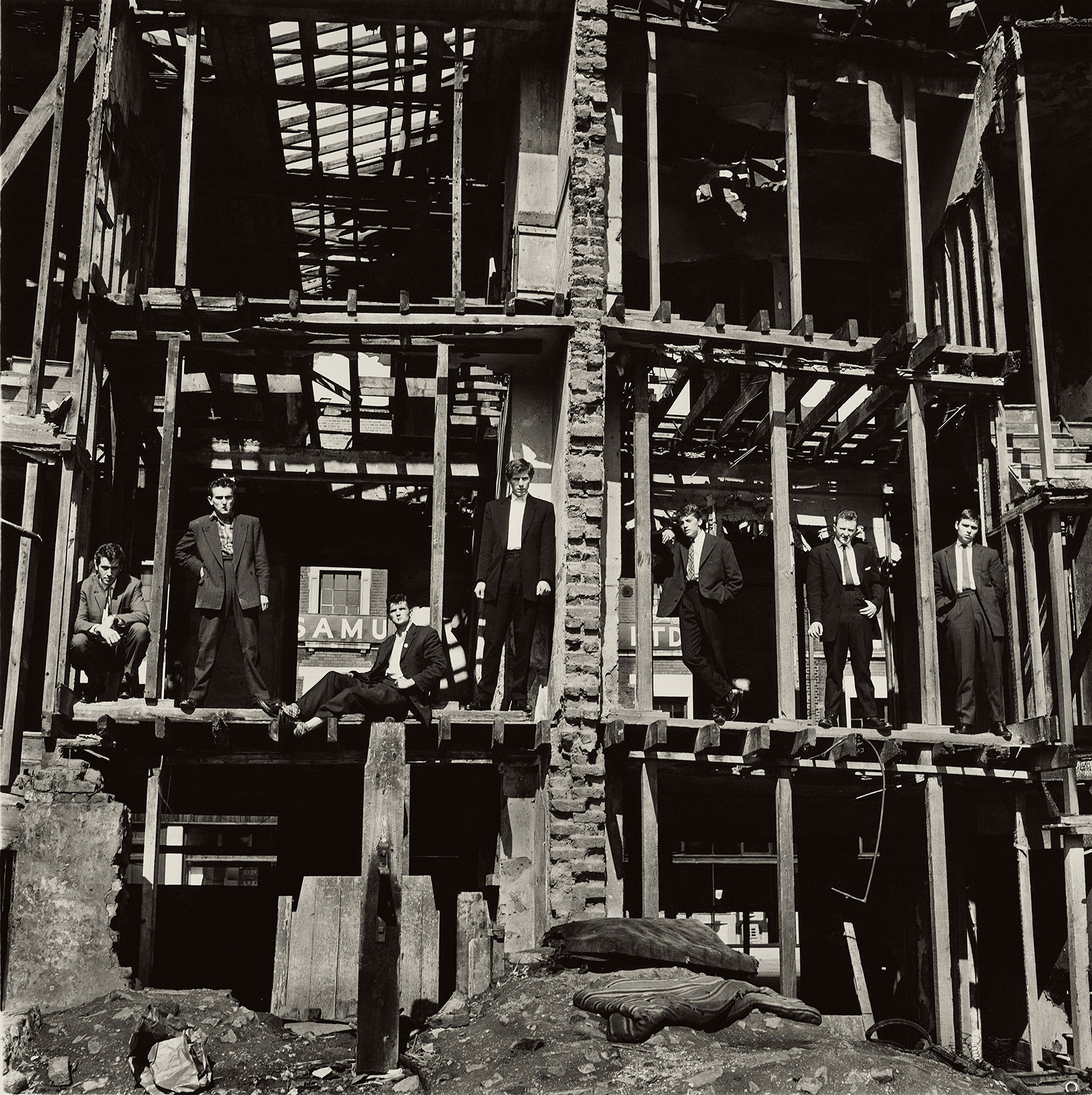

The Guvnors in their Sunday Suits, Finsbury Park, London, 1958, by Don McCullin. © The artist

Yet McCullin hates being categorised as just a war photographer – ‘a reductive term’ he says, when we speak on the phone. The exhibition reflects the many hours McCullin spent as a young man photographing the streets of London. Indeed, his first break with Fleet Street came when a newspaper published a photo of a local gang of street urchins known as the Guvnors, ordered together in a bombed-out house. They had grown boys notorious after the murder of a policeman, but McCullin would routinely knock about with them, and easily got insider access.

‘I started out in photography accidentally,’ he notes in the exhibition. ‘A policeman came to a stop at the end of my street and a guy knifed him. That’s how I became a photographer. I photographed the gangs I went to school with. I didn’t choose photography, it seemed to choose me, but I’ve been loyal by risking my life for 50 years.’

The exhibition is notable for the number of photographs taken in parts of London that now teem with restaurants and cafés and shops and new-build complexes: Shoreditch’s Old Spitalfields Market, Liverpool Street and Commercial Road, for example. When framing the many destitute people he captured in those early years, he remembers: ‘I would make myself unimportant in the presence of such people, to let my eyes meet their eyes, so I could become drawn into their vision.’

Near Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin, 1961, by Don McCullin. © The artist

The exhibition includes a series of photos McCullin took of the Berlin Wall as it was first being built in 1961. McCullin was 26, and, in his own words, ‘a rank amateur’. The American and Soviet militaries were eyeball to eyeball in the centre of Berlin. ‘I was sat on the hottest story in the world.’

McCullin was straight off the flight from London with roughly £20 in his pocket. He had no knowledge of international affairs, nor had he experience of the aesthetic rigour needed to shoot a story of such calibre and significance. He simply persevered, shooting again and again from as many angles as he could find. The tension and division of the scene (and the Berliners attempts to carry on with their lives as usual) is still bitingly evident in his photographs, even in the serene calm of the Tate Britain.

RELATED STORY

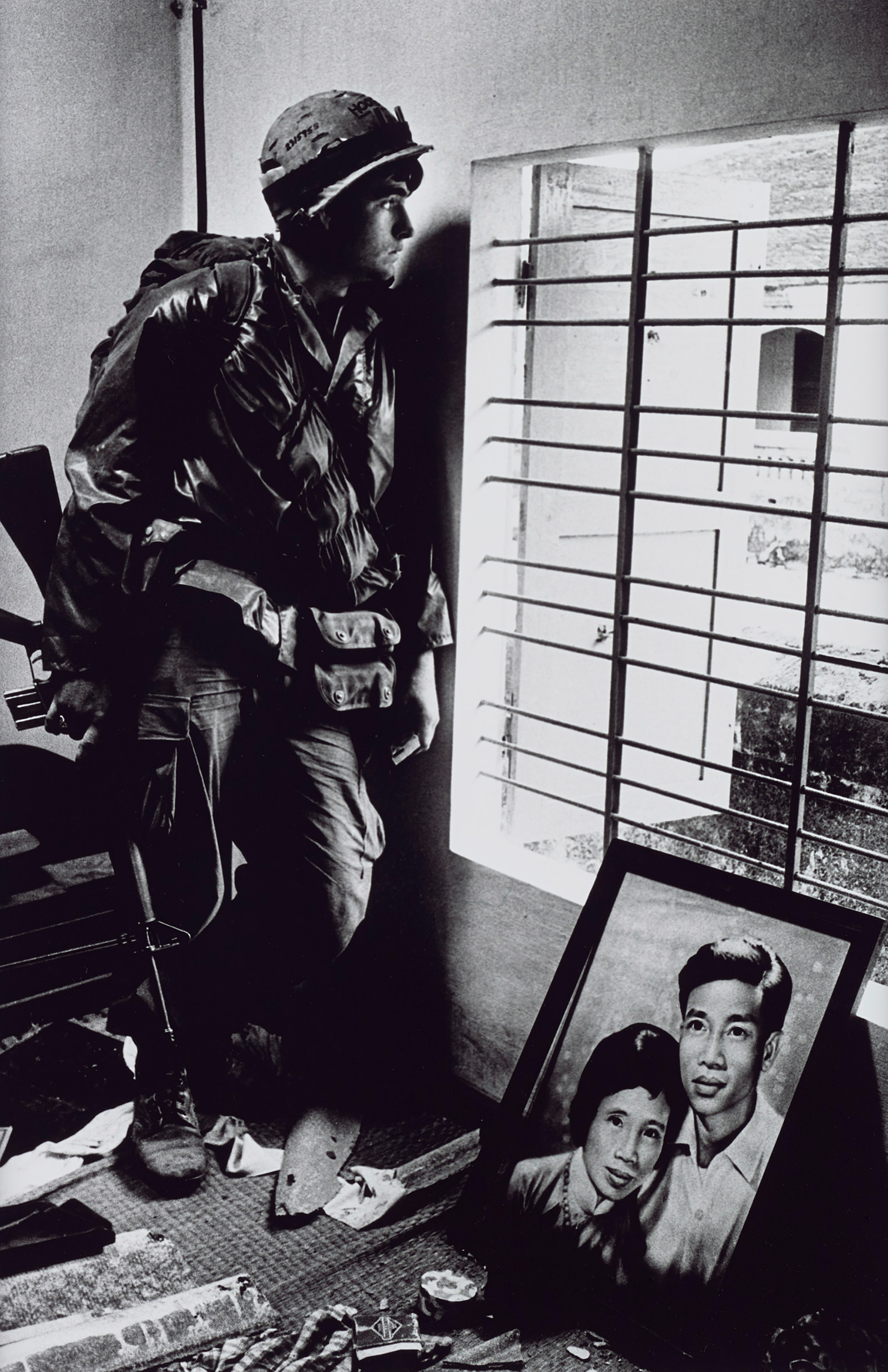

The Berlin images launched his career in the heyday of the newspaper era. For the next few decades, the photographs of McCullin (and a few of his contemporaries) were often the only thing connecting the British people to the brutal realities of war in faraway places. Some of his images have since become iconic, like the Northern Irish youth in the black suit brandishing a bit of plywood against the occupying British army. Or, of course, the shell-shocked American GI in Hue, Vietnam – ‘he didn’t blink once.’

But there are other pictures in display that have never entered the public consciousness, and, indeed, were not noticed by McCullin until he revisited his contact sheets for this exhibition. One shows a senior Biafran soldier bent over the corpse of a dead comrade. ‘I saw the commander talking to one of the dead soldiers as if he were still alive,’ McCullin says. ‘He was praising the man’s courage and thanking him on behalf of the Biafran nation. It was moving and alarming at the same time.’

Some of the adjoining images, of starving women hopelessly trying to breastfeed their babies, are almost impossible to look at without feeling a deep sense of despair. McCullin says of the Biafra civil war and famine of 1968: ‘It was beyond war, it was beyond journalism, it was beyond photography, but not beyond politicians. We cannot – must not – be allowed to forget the appalling things we are all capable of doing to our fellow human beings.’

I didn’t choose photography, it seemed to choose me, but I’ve been loyal by risking my life for 50 years

The Tate exhibition underpins what a brilliant war photographer McCullin undoubtably is. For he has an ability, amid the violence and the chaos and the endless churn of tragedy, to create imagery that seems elevated by a higher message. ‘I make it possible for you to look at them and try to come to terms with them,’ says McCullin.

Forcing himself to so consistently bear witness in such a way has wrought a great toll. ‘I wasn’t a great family man,’ he reflects. ‘My children were always waving goodbye to me. Would my children look at me and think “Is he not going to come back?” I can’t claim to have been a great father. I sacrificed their childhood for my photography.‘

McCullin has lived in Somerset with his third wife for 35 years. It’s only now, in his eighties, that he has found a degree of peace, and been able to experience his children’s lives, and married life, without the turmoil of knowing he would soon have to return to the frontline.

Woods near My House, Somerset, c1991, by Don McCullin. © The artist

The exhibition ends with the very beautiful photographs McCullin routinely takes of the bucolic landscapes around his adopted home. ‘The landscapes became a process of healing,’ he explains. ‘It was a way to forget about wars and revolutions and dying children.’

He recalls the experience of re-entering the darkroom for this exhibition, where he developed new prints from the original negatives that pile up in the spare rooms of the house. ‘They actually talk to you,’ he says. ‘They remind you. I take those memories to bed with me, have terrible dreams and wake up in a sweat. They have contaminated that house.

The Battle for the City of Hue, South Vietnam, US Marine Inside Civilian House, 1968, by Don McCullin. © The artist

Seaside pier on the south coast, Eastbourne, UK, 1970, by Don McCullin. © The artist

INFORMATION

‘Don McCullin’ is on view 5 February – 6 May. For more information, visit the Tate website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

ADDRESS

Tate Britain

Millbank

London SW1P 4RG

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.