Artist Emily Hass confronts displacement through the poetry of architecture

Through the language of architecture, New York-based artist Emily Hass examines cross-generational forced migration and the psychological power of home

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

What does it mean to feel at home? What does it mean to lose it? Such questions about displacement and exile inform the practice of New York-based artist Emily Hass, and are also woven into the fabric of her family history.

While global in scope, Hass’ work is grounded in New York, where she works from her studio on Avenue A, near Tompkins Square. ‘There's something about the energy of Manhattan that is a part of my work’, she says via Zoom with infectious enthusiasm. ‘I want my inspiration with me in the [studio] space. I do warm-ups with building blocks and just play for a while.’

Hass, who has graduate degrees in psychology and design from Harvard University, uses architectural codes to explore humanity’s sense of place. ‘To me, [psychology and design] are inextricable. We are influenced by our environment, and we express ourselves in our spaces.’ Her long list of artist influences includes Gordon Matta-Clark, Mike Nelson, Lygia Clark (notably her architectural ‘critters’), Lygia Pape, Fred Sandback, Eva Hesse (her fearlessness, and shared history with Hass’ father, who also escaped Nazi Germany), Doris Salcedo and Zarina Hashmi.

Portrait of Emily Hass in her Avenue A studio featuring Water Shape Canvas, 2021 (left) and String-Nail composition, 2021 (behind)

Hass’ material palette is diverse and symbolic. Her works on paper – often using ink, gouache, nails and string – are intricate, spectral depictions of fragmented building blueprints, like pieces of a puzzle. Other projects have involved construction materials: burlap and house paint to represent homes left behind by refugees coming to Berlin from Syria; and cement casts which echo the cinderblock often exposed after buildings are bombed.

‘Architecture is a way into someone’s personal story and also the story of a community or a society, Hass explains. In 2000, she began observing the results of New York’s construction boom. When structures were demolished, the outlines of their floors and walls remain on the adjoining buildings. Through photography, collage and stitching, she documented these architectural ‘ghosts’ in a series called Sides in which abstracted vestigial shapes told the stories of structures that once were, a two-dimensional echo of a three-dimensional history.

Emily Hass' Altonaer Strasse, 2 Sewn 4, 2008 canvas strands and paper, made using the archival architectural records of the former residence of Anne (née Berger) and Bernhard Hass

In 2006, Hass turned her focus to her own family history: her Jewish father, Gerald Hass had fled Berlin in 1938, under the threat of Nazi persecution. The artist travelled to Berlin to conduct research in the city’s Landesarchiv (architectural archive). She located the original plans of the demolished building on Altonaer Strasse where her father once lived, and used these as a basis for her artwork. These pieces, mostly gouache on old, found, and sometimes damaged paper, sought to ‘recognise the loss of this property both as a historical fact and a trauma of displacement’.

What began as a deeply personal project would soon grow in breadth and depth, and form the building blocks of an ongoing series. Hass continued to research the Landesarchiv records from the 1930s, uncovering the homes and workplaces of persecuted artists and intellectuals including Josef and Anni Albers, Marta Löffler and Lion Feuchtwanger, Else Ury, Walter Benjamin, Lyonel Feininger, and Charlotte Salomon. As Hass explains in her new monograph Exiles: ‘I used the archival architectural records to make visible the lives that were abandoned under duress. Home by home, I documented the profound cultural loss Berlin experienced as a result of the purges orchestrated by the Third Reich, a loss of both individual citizens and of a creative tradition.’

Works inside Hass' studio, including Kites, 2021 (pictured on black wall, upper), maple dowels, nails. Kites is part of the new work Hass is developing that addresses forced migration and displacement, and is a collaboration with Jim Vercruysse, a cabinetmaker on Martha’s Vineyard

In 2016, after ten years of exploring the lives of those exiled during the Second World War, Hass’ focus shifted. She began drawing links between the persecution of Jews and a more contemporary crisis. Berlin had once been a place to flee from. It is now a destination for migrants – particularly those from Syria – to flee to, or through. In 80 years, the city had transformed from a place of peril, trauma and exodus, to a haven of safety, yet still central to the plights of those seeking refuge.

Hass began volunteering at Flughafen Tempelhof, a disused airport transformed into Berlin’s largest refugee camp. She struck up conversations with its inhabitants. They described their homes, sometimes drew them and shared photos. She recalls one conversation with a young Syrian architect, whose brother had been killed and whose parents remained in war-torn Syria. ‘She said, “I can’t look at pictures of home, but when I feel I’m losing that connection, I draw it. Then I throw that piece of paper away”, I thought that was incredible and poetic.’ Hass recalls. Though her familial experience has informed her approach to subjects around displacement, exile and the plight of refugees, she treads lightly. ‘I don't want to appropriate anyone else's experience,’ she says.

Top: Hass pictured with Transom, 2021 birch plywood, wall paint, a collaboration with Jim Vercruysse. Above: works inside the artist's New York studio, including Kite configuration, 2021, maple dowels, gesso, nails (facing wall)

Research then took her to Athens where she met individuals and organisations involved in refugee resettlement. Many refugees arrived in Europe through Greece via perilous water crossings, a subject Hass probes in the recent series Water Shapes (2021), a series of geometric plywood forms that Hass placed on the water's edge on Martha's Vineyard and filmed. Evocative of makeshift boats, the fragments broke apart and reunited in different compositions, all at the mercy of the sea.

When Covid-19 hit, Hass moved to be with her father – now in his late eighties – in Martha’s Vineyard. There, she set up an ad hoc studio in her late mother’s pottery workshop. ‘It was really meaningful to be with her memories and spirit, but also to have a place to work during those many months. Out of necessity, I was working outside. I wanted to work bigger, and also embrace the place, just be in nature, and think beyond the studio,’ she says.

‘While we were living together in isolation, my father began (unprompted) to reflect on the parallels between the dislocations caused by the coronavirus and his own childhood displacement’, Hass recalls in Exiles.

Flensburger Strasse, 11 Façade, 2011 gouache on vintage paper (framed work) made using the archival architectural records of the former residence of Kurt Weill

Her work distils lost moments like these, which are fractured, fragmented and reassembled into something universal and cross-generational. Though deeply personal, Hass' work is not prescriptive; it leaves space for external interpretation so that others might inhabit these voids with their own experiences.

‘A lot of the subjects I make work about are pretty devastating. There are times when I’m like “why am I taking this on?”’, says Hass, who is also exploring fears of future mass displacement due to climate change. ‘But I come away feeling more hopeful and more impressed by humanity and our ability to keep going. I learned that from my dad and his attitude to what he escaped.’

For Hass, the complex and multifaceted human need for home is not about nostalgia or comfort. It’s about how losing a sense of home leaves a gaping hole in our ability to flourish as humans. The loss of place represents a deeply personal wound, and mass displacement is a fracturing of an entire collective identity. She uses architecture and buildings as a language, as a story-telling device for the movement of people, and what they leave behind. She uncovers stories of trauma, but also stories of strength.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

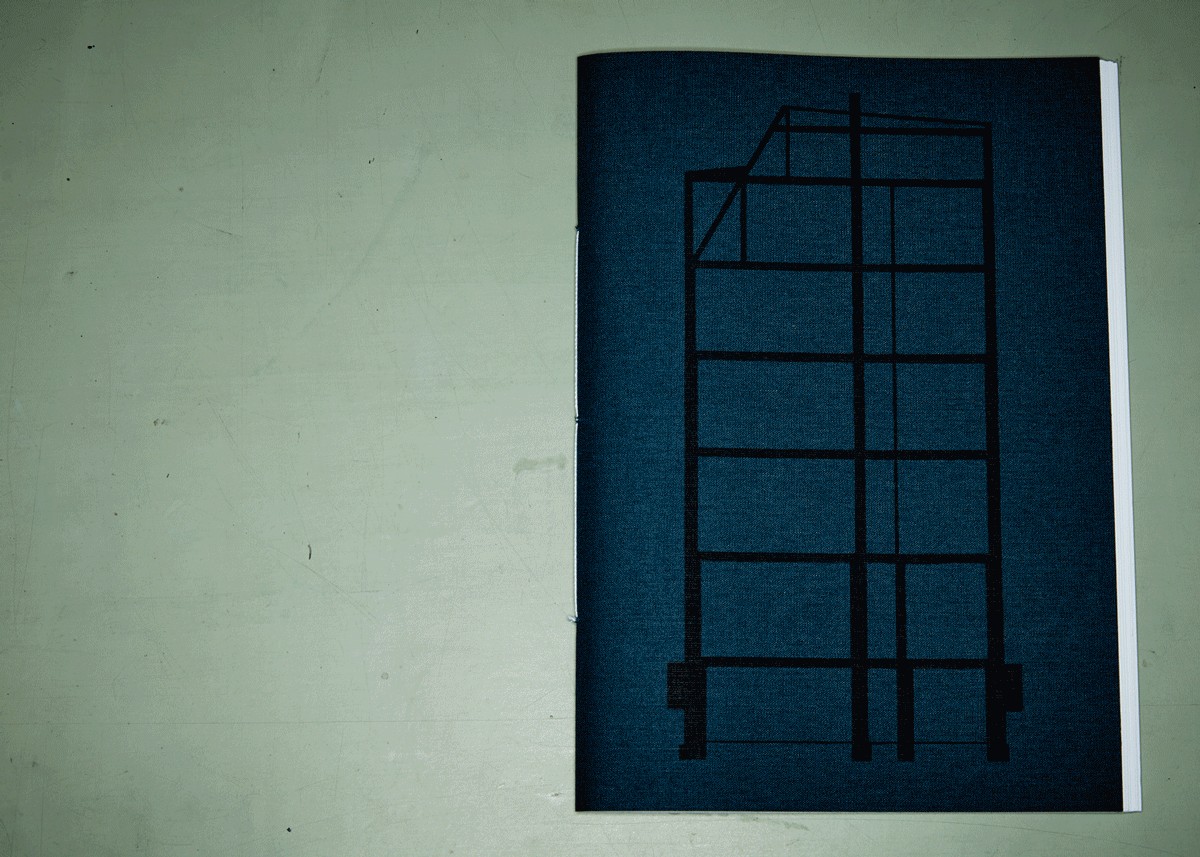

Spreads from Emily Hass' new book Exiles. It explores the parallels between forced migrations during WWII and current mass displacement in Syria and elsewhere and incorporates reflections on the themes of home, security, and identity in the context of the pandemic. Exiles is a collaboration with Mike Dyer of Remake Design, and includes contributions from artist Edmund de Waal, and curator and cultural heritage historian Kristin Parker, with the support of Frank Williams, a longtime collector of Hass' work

A table in Emily Hass' New York studio table featuring finished works and works in progress

Works in Emily Hass' studio. Left to right: Untitled, 2019, found wood, house paint; Untitled, 2021, found wood, vintage wood samples, gesso; Paper Bags, 2021, vintage paper bags, gesso; Untitled, 2019, burlap, wall paint

INFORMATION

Emily Hass’ book, Exiles is created in collaboration with designer Mike Dyer with contributions from artist Edmund de Waal and curator and cultural heritage historian Kristin Parker.

Exiles is available at 192 Books (192 Tenth Avenue New York, 192books.com); Familiar Trees (47 Railroad Street, Great Barrington, MA, familiartrees.com) and online at Katherine Small Gallery (ksmallgallery.com)

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.