Buckhorn Sculpture Park: inside the art paradise dreamt up by collectors Sherry and Joel Mallin

As legendary art collectors Sherry and Joel Mallin prepare to sell their upstate New York home – and the star-studded collection occupying Buckhorn, its onsite sculpture park – we go behind the scenes of this art treasure trove, and the extraordinary life, work and spirit of the Mallins

Photography: Hugo Yu

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

On a wooden gate leading into Buckhorn, the upstate New York property of collectors Sherry and Joel Mallin, a sign cautions trespassers that there is art ahead. Before the Mallins consigned the home and their collection of over a thousand pieces of contemporary art for auction, peppered throughout the 15-acre landscape – anointed Buckhorn Sculpture Park after they began inviting members of the public to tour the grounds – was a series of outdoor works by Louise Bourgeois, Anish Kapoor, Sol Lewitt, among others, amassed over four decades. They were arranged in a scattered fashion so as to encourage a journey of discovery. (Viewers, Sherry recalls, came dressed in sneakers rather than high heels.)

In one area was a site-specific installation by Richard Serra; elsewhere, a purpose-built art barn completed in 2000 to rival the best contemporary art museums, housing works that could not be displayed on the limited wall space of the main house. At its fullest, the outdoor collection encompassed 70 sculptures, 31 of which will go to auction at Sotheby’s this month, following a landmark sale in London and New York of works by Robert Gober, François-Xavier Lalanne, and Yayoi Kusama.

Robert Perless, Mobius, 1992, mirror polished stainless steel and polymer prisms

Francis Outred, an independent art advisor who previously headed up contemporary art at Sotheby’s, first visited Buckhorn in 2007, when the Mallins were selling a Damien Hirst pill cabinet, titled Lullaby Spring. Made of stainless steel with thousands of handmade pills attached to it, the piece sold for the record price of $19.2 million.‘They really looked after everything as if it was their own,’ he recalls.‘They have six children between them, but they also had a huge amount of other babies here.’

The Mallins have known each other since they were 14-year-old students at the Bronx High School of Science, and subsequently became classmates at Cornell University. They rekindled their friendship in the early 1980s, when both were recently separated from their spouses, and eventually married. Joel, a lawyer who at one time represented Lou Reed, was already a prolific collector of surrealist art, accumulating a litany of works that Sherry, an options trader then uninitiated into the world of collecting, found unpleasant at the beginning of their relationship.

Jeppe Hein, Mirror Angle 30/60/120, 2009, Aluminum, high polished steel

‘The house was filled with surrealist art of the highest order and I thought it was all awful,’ she remembers. ‘It’s terribly grotesque and I hate all of it. And he said, “Well, you’re only saying that because you know nothing about art, but if you hang out with me, you’ll eventually get to understand it and you won’t feel that way.”’ The two joined a contemporary art class at New York University, and spent their first few years together collecting only Picasso prints. Sherry, who had once studied dance with Martha Graham, found herself drawn to a Cy Twombly painting from the Roman Notes series, its brushstrokes bringing to mind pirouetting dancers.

Thus began a passion for work to which the Mallins felt an inexplicable personal connection. They believe their collection is a mirror of who they are as people. They have never relied on the advice of critics or specialists, operating instead on the undefinable feelings that a piece of art evokes.

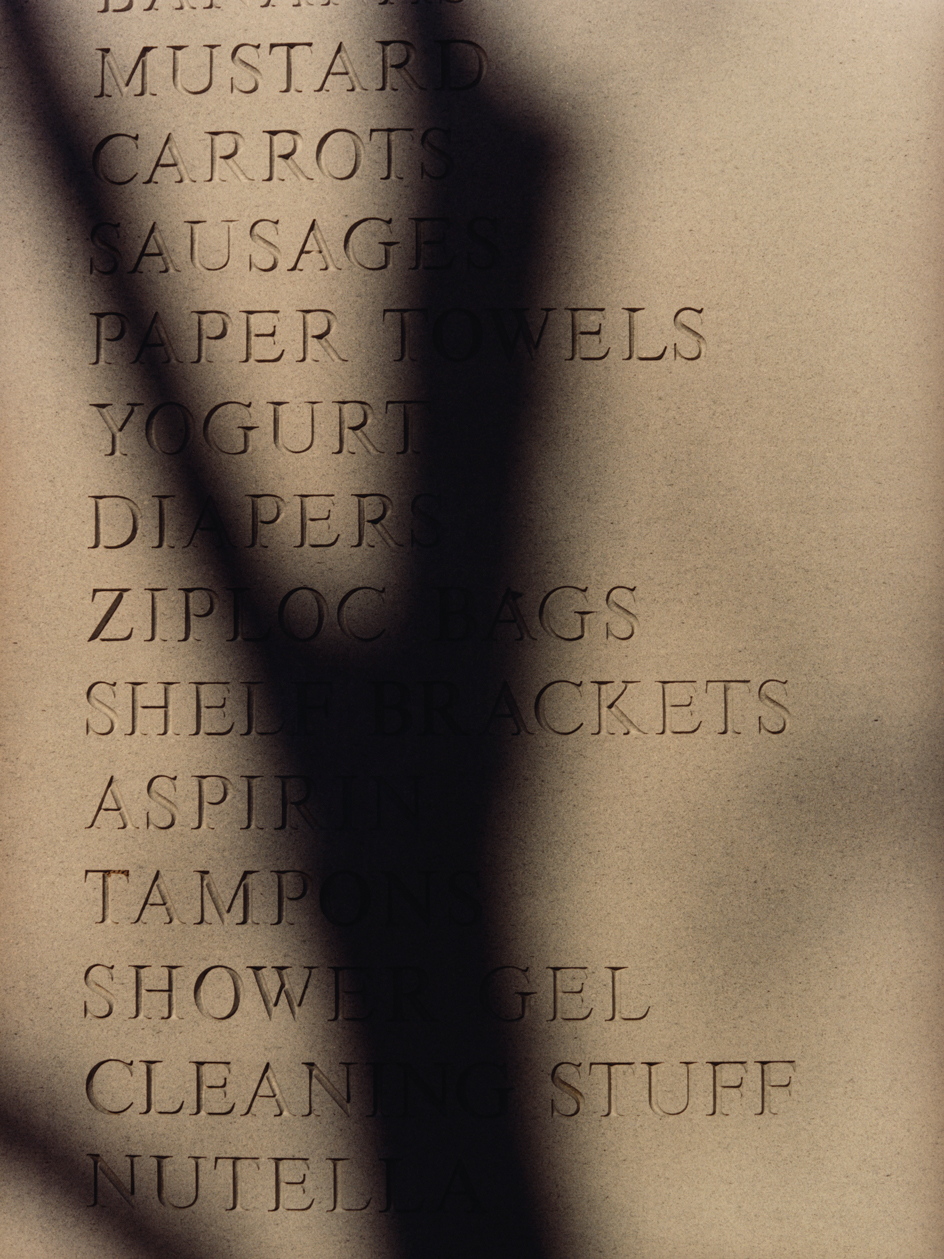

David Shrigley, MEMORIAL, 2016, granite,

The process can seem mysterious to outsiders. Once, during a private showing, a gallerist offered to leave the pair alone so they could discuss the piece. ‘And I said to him, “No, you don’t have to leave us alone to talk about it, we’ve already talked about it,”’ Sherry remembers. Not a single word had been exchanged between the two.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘But we came, we looked, we each looked separately, closely, we stepped back, and we looked at each other and we told each other immediately yes. And if you ask me why, I can’t tell you why. I don’t know,’ she says. Outred calls it their gut instinct.

The unspoken alchemy that informs the Mallins’ collecting strategy has nevertheless allowed various threads to organically emerge across the works: memory, the body, life and death, the passage of time. Outred believes the collection is difficult to qualify in terms of universal themes, but that the Mallins have often been attracted to art that you can touch and feel, that engages with the nature of human existence, and what it means to be alive. The outdoor artworks (among them pieces by Berlinde de Bruyckere, Jeppe Hein, and Dan Graham) range from the whimsical and joyous to the morbidly humorous: a neon, Perspex ‘Hell, Yes!’ by Ugo Rondinone; César’s Le Pouce; David Shrigley’s Memorial headstone in granite, inscribed with a list of grocery items: diapers, cheese, Ziploc bags, Nutella, tampons.

Berlinde de Bruyckere, Lost In Lead II, 2012-2013, 2013, lead, bronze, Belgian granite, epoxy, inox

Many of the artists whose works the Mallins collected became personal friends, and what they call their ‘art children’, among them the sculptor Liza Lou, whose Trailer and Closet they donated to the Brooklyn Museum and the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, and Mike and Doug Starn, who recently made portraits of the couple, and often joined holiday dinners at Buckhorn.

‘There was always room at the table for another person, and we almost always had an extra bed somewhere,’ Sherry recalls. The pair acted as both patrons and parents, collecting works while also forging profound relationships with their creators.

As they part with the collection, there is sadness, and a sense of inevitability. They never believed that they truly owned the works, but were given the privilege of being caretakers for the time they were housed at Buckhorn.

Lessons can be drawn from the last 40 years. Joel’s advice: ‘You shouldn’t try and make money on the art that you collect. It’s a fool’s errand.’

Sherry: ‘We’re not talking about building an art collection for a museum, we’re talking about living with it in your own home, so you better like it.’

Deborah Butterfield, Makili, 1995, patinated bronze

Some years ago, after retiring from their positions on various museum boards, the pair continued to be sought out by art friends for their wisdom. ‘We’re not gossipers, if you tell it to us, it stays with us,’ Sherry says. What would later become known among insiders as the infamous ‘Mallin breakfast’ was born, whereby Joel and Sherry would provide counsel to artists, critics, museum directors, and gallerists at their apartment in Manhattan.

The meetings lasted an hour, from 8.30 to 9.30, during which peace pacts were brokered between various parties, over bagels, cream cheese, smoked salmon, Joel’s scrambled eggs, fresh fruit, and coffee. Often, people came with their personal problems as well as their art problems – questions about raising a family, and what you do when you have a baby. Canvases were pressed up against the windows and covered the view of Central Park, Lou remembers. ‘For them, the scene outside was like a bad landscape painting. They cared about art and they cared about friendship. That’s the Mallins.’

Kathy Ruttenberg, In Sync, 2018, cast silicon bronze, polychrome patina, cast concrete

Ursula von Rydingsvard, Untitled, cedar and graphite

‘A Life in Art: Sculpture from The Mallin Collection’ will go on view in Sotheby’s New York galleries from 18-23 February 2023, before all works will be included in a live auction at 10am on 22 February, and online sale which will close for bidding the following day. sothebys.com