'What does it mean that the language of photography is invented by men?' Justine Kurland explores the feminist potential of collage

'The Rose,' at the Center for Photography at Woodstock (CPW) in Kingston, New York, examines the work of over 50 artists using collage as a feminist practice

‘I’m very excited that there’s this possibility, to see the revolution coming from the Left again,’ says Justine Kurland by way of introduction. The photographer, best known for her Girl Pictures series, is speaking from her home in New York the day after the polls closed, indicating Zohran Mamdani’s win as the Democratic candidate for New York City Mayor. ‘I’m thinking about what’s happening politically, also, because so much of why me and Marina wanted to do this show was to look at artists who include activism in their practice, and thinking about how art matters so much right now – in imagining a place where we can bring culture politically forward, and as forms of resistance; what tools we have when we feel so disempowered, in this country, as we slide into fascism.’

K8 Hardy,Collage (ABOUT THIS ISSUE), 2015

Now in its second iteration, The Rose, named after Jay DeFeo’s monumental painting made between 1958-66, and curated by Kurland and Marina Chao at the Center for Photography at Woodstock (CPW) in Kingston, New York, was originally conceived by Kurland with Sarah Miller Meigs and Libby Werbel for a show at The Lumber Room in Portland in 2023. A survey of collage as a feminist practice, potent protest tool and corrective process, The Rose features more than fifty artists working between the 1960s through to today, amongst them Hannah Wilke, Deborah Roberts, Wendy Red Star and Frida Orupabo. This month, the project is further extended with a new book, The Rose: A Circular Genealogy of Collage.

The publication is a sort of follow up to Kurland’s 2022 SCUMB Manifesto, which saw her cut up and collage the pages of her own vast library of photobooks by white, male photographers (Chao, with whom the photographer has long collaborated, contributed an essay called ‘Cunts with a Kitchen Knife: Notes on Feminist Collage and Torn Paper’, a reference to Hannah Höch’s 1919 photomontage Cut with the Kitchen Knife; the book itself borrows from Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto). ‘I started cutting up my books in 2019, which had a lot to do with my own political awakening and the first Trump administration,’ offers Kurland, reflecting on the project’s genesis, which began three decades into her photographic career. ‘I also started dating a woman who was very critical of my library.’

Frida Orupabo Peony, 2022

In the new book she writes of collage as ‘a conduit to solidarity with other artists.’ Today she adds, ‘For me specifically, there was something about getting rid of, very literally, the physical space on my bookshelf that these canonised male photographers occupied. Now I can think about all of these other ways that photography can operate; breaking out of what a master photographer is, you can have a more nuanced appreciation for other perspectives.’ The anthology What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843 – 1999, by 10x10 Photobooks, additionally informed this approach, especially in relation to the language employed when shaped solely by one gender. ‘There's no part of our political world that's not touched by photography, so what does it mean that the language of photography is invented by men? That they have this monopoly on a language that we all use every single day?’ considers Kurland. ‘I think collage is uniquely poised to really take apart the kind of insidious baggage that comes with language.’

For her part Chao, whose previous exhibitions include 2018’s Multiply, Identify, Her, an intersectional group show exploring the self, The Rose provided an opportunity to broaden people’s understanding what is typically classified as collage. ‘I've always wanted to think about collage and things that aren't cut paper collage, or actually aren't assemblages,’ she says, recalling the various mediums at CPW, which include video, ceramics, textiles and paint. ‘These kinds of things all speak to each other, and we're both really interested in how expansive and inclusive conversation about collage – feminist approaches to collage – could be. The nowness and the urgency, how important it is to be talking about this sort of liberatory potential of collage, is also something that this show has really imparted on me.’

Wendy Red Star, From Set F: iichíilishihche datchípeetaaliche (martingale); iíttaashteeuuxe (buckskin dress); baleiipáhpaatbaalo (beaded belt) and bálaaisshe (purse); baaísshikshe (saddle bag), 2023

‘In general, we've all seen a lot of shows like this,’ she continues, ‘But this is a very specific offering, near 60 artists, a third of whom came to an artist talk– that's not typical. That makes the energy of the show very different than anything I've ever worked on.’ Indeed, a sense of community runs through The Rose, almost independently of the curators’ intentions; many of those participating have previously done residencies at CPW, something neither Kurland or Chao were privy to when building this version of the show. ‘I think The Rose, in a way, is about a movement that's happening in photography and in New York, and that movement is part of what CPW is about,’ notes Kurland.

The Rose until August 31st at the Center for Photography at Woodstock (CPW) in Kingston, New York

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Zoe Whitfield is a London-based writer whose work spans contemporary culture, fashion, art and photography. She has written extensively for international titles including Interview, AnOther, i-D, Dazed and CNN Style, among others.

-

High in the Giant Mountains, this new chalet by edit! architects is perfect for snowy sojourns

High in the Giant Mountains, this new chalet by edit! architects is perfect for snowy sojournsIn the Czech Republic, Na Kukačkách is an elegant upgrade of the region's traditional chalet typology

-

'It offers us an escape, a route out of our own heads' – Adam Nathaniel Furman on public art

'It offers us an escape, a route out of our own heads' – Adam Nathaniel Furman on public artWe talk to Adam Nathaniel Furman on art in the public realm – and the important role of vibrancy, colour and the power of permanence in our urban environment

-

'I have always been interested in debasement as purification': Sam Lipp dissects the body in London

'I have always been interested in debasement as purification': Sam Lipp dissects the body in LondonSam Lipp rethinks traditional portraiture in 'Base', a new show at Soft Opening gallery, London

-

Arthur Tress’ photographs taken in The Ramble are a key part of New York’s queer history

Arthur Tress’ photographs taken in The Ramble are a key part of New York’s queer historyThe images, which captured gay men, like Tress himself, cruising around the Central Park woodland in 1969, are the subject of a new book

-

Jan Staller’s Manhattan Project is an abstracted chronicle of a city under construction

Jan Staller’s Manhattan Project is an abstracted chronicle of a city under constructionThe photographer Jan Staller shows another side of New York’s relentless change with this portfolio of dynamic, sculptural images

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week'Tis the season for eating and drinking, and the Wallpaper* team embraced it wholeheartedly this week. Elsewhere: the best spot in Milan for clothing repairs and outdoor swimming in December

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s been a week of escapism: daydreams of Ghana sparked by lively local projects, glimpses of Tokyo on nostalgic film rolls, and a charming foray into the heart of Christmas as the festive season kicks off in earnest

-

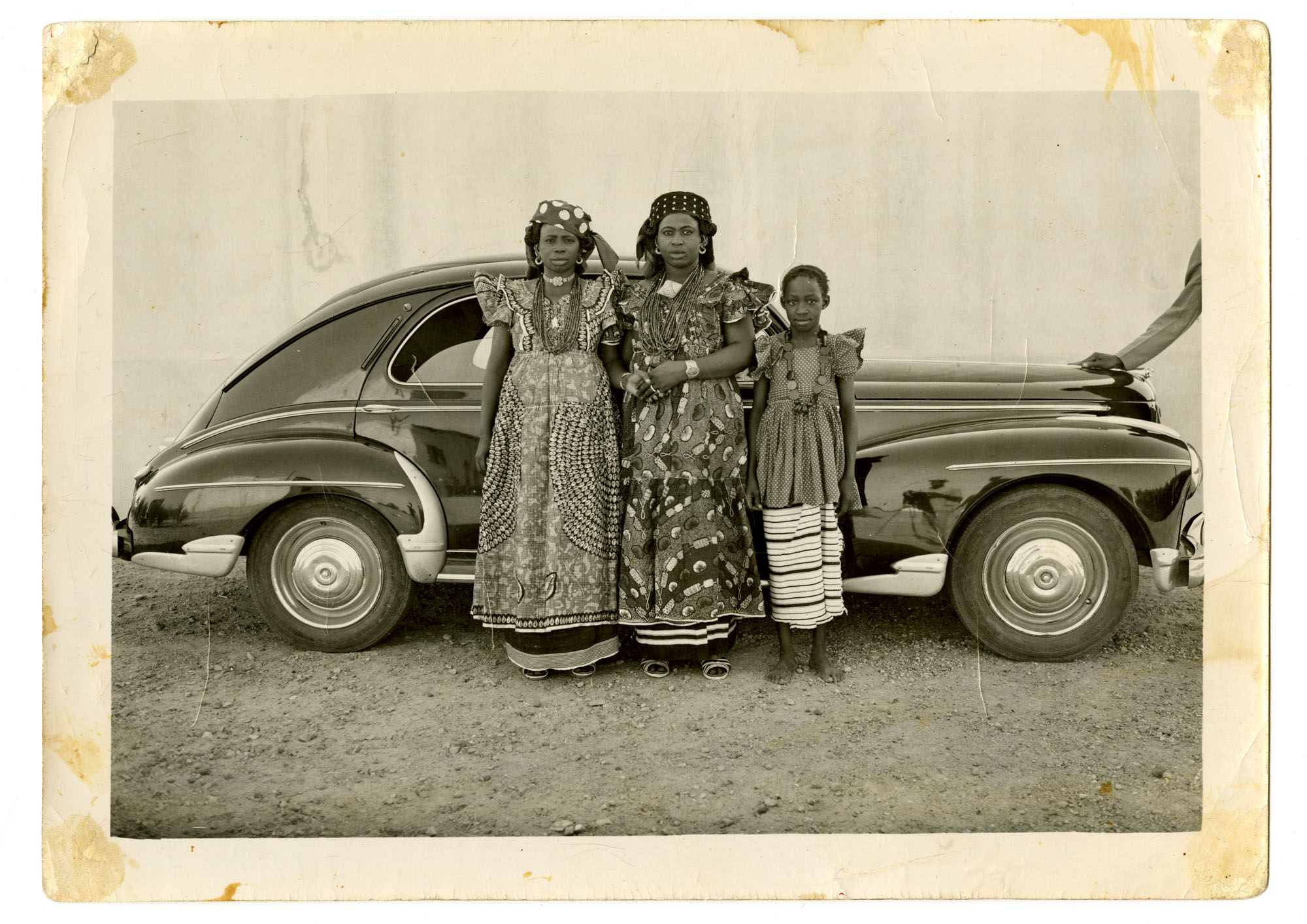

Inside the work of photographer Seydou Keïta, who captured portraits across West Africa

Inside the work of photographer Seydou Keïta, who captured portraits across West Africa‘Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens’, an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, celebrates the 20th-century photographer

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekFrom sumo wrestling to Singaporean fare, medieval manuscripts to magnetic exhibitions, the Wallpaper* team have traversed the length and breadth of culture in the capital this week

-

María Berrío creates fantastical worlds from Japanese-paper collages in New York

María Berrío creates fantastical worlds from Japanese-paper collages in New YorkNew York-based Colombian artist María Berrío explores a love of folklore and myth in delicate and colourful works on paper

-

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekAs we approach Frieze, our editors have been trawling the capital's galleries. Elsewhere: a 'Wineglass' marathon, a must-see film, and a visit to a science museum