Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

'At this point in life I don't like titles – “street photographer”, “documentary photographer”, I’m tired of all that,’ laughs Jamel Shabazz. 'I’d call myself a documentarian. I’m just recording things on my personal journey. My camera is my compass. It allows me to see things in the world that I wouldn’t see otherwise. I go with the flow, meet people and learn.'

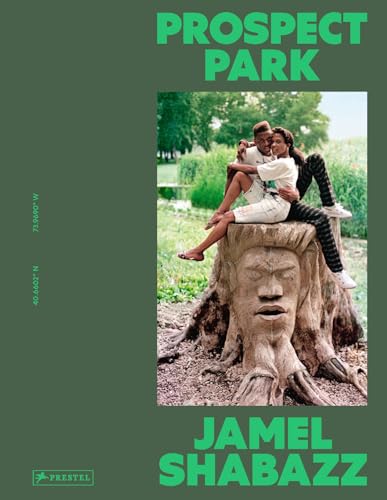

Shabazz – a US Army veteran-turned-career prison officer, retired early to turn unofficial social worker, mentor and, yes, photographer – is looking back over the images in his new book Prospect Park, a compendium of shots he took in Brooklyn’s own answer to Central Park from 1980 to 2025. A favourite of his shows three women, seen from behind, perched together on a low tree branch: it turns out that they had been visiting that same spot every year since junior school to just sit for the day and reminisce. Shortly after the shot was taken, a hurricane took the tree.

Prospect Park, 2008

'Everyone I’ve met in the park has had a story and without my camera – and the portfolio I’d carry with me, which helped show I was sincere – I wouldn’t have had those conversations,' says Shabazz. 'But life is slower in the park. People are more at peace, so they’re easier to photograph. I have vivid images of going to the park as a child, where the air is clean, where I saw a lake for the first time. It was an oasis, and when I was older, I realised I had to get back there, and kept going back there, to jog, to meditate, always with my camera. And it hasn’t changed at all. I can go there now and get the same feeling.'

The park also provided Shabazz with some relief, not least from the fact that his day job was a litany of desperation and brutality in a ceaselessly hostile environment. It was an opportunity just to talk to people and make connections, a process in ways more important than the photos that came out of it. 'It was an opportunity just to see humanity in a different space, to share my story, hear theirs, maybe be a big brother to the younger guys facing challenges in their lives,' says Shabazz. 'And everyone I met had a story [such that it] felt like there was a reason for that meeting.'

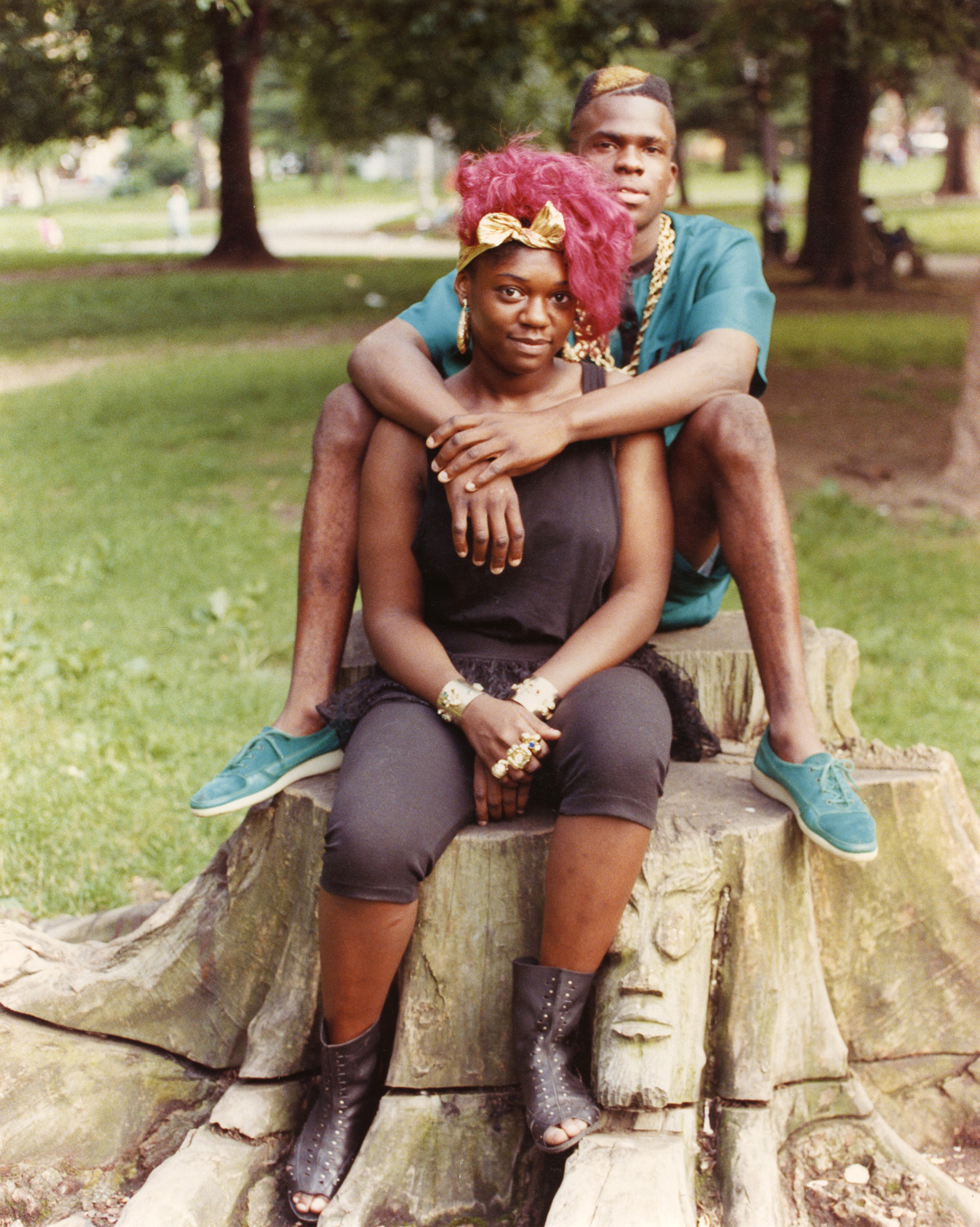

Prospect Park, 2014

Prospect Park, 1986

Nonetheless, his Prospect Park pictures – families, couples, hobbyists, party people, dreamers, wanderers, 'a lot of love and joy' – are at the gentler end of the photographer’s work. As a child of the era of Life, National Geographic and Playboy – 'magazines that created a whole visual language and a way of seeing the world' at a time when photography was arguably a more critical medium – it was perhaps inevitable that Shabazz’s work has more often focused around harder-hitting social commentary: prostitution, race, homelessness, Aids, the crack epidemic. 'Sometimes I feel like I’ve only seen those [bleak] kinds of images,' he laments. Right now, he’s volunteering in an animal shelter and working on a project about animal welfare.

'I have a profound love of dogs, and the dog I was raised with was the greatest gift I ever had besides a camera. Actually, I’m getting a little tired of humans right now with everything going on, with all the hatred,' says Shabazz. 'But my father [an official US Army photographer] taught me always to have themes, so when I go out of the door I have at least ten in my mind. My eyes are open, my camera locked and loaded and I’m ready to observe.'

Prospect Park, 2014

Prospect Park, 1995

Shabazz says that his decades of shooting Prospect Park photographs were not only a relief from the gloom; today he loves social media, he says, 'because those incredible images feed my mind, but they also cause a lot of pain to see how bad things are too'. The park photographs were also an attempt to provide a counter-narrative. Look, they seem to say, we’re more alike than you imagine. We can get on with grace and good humour. We can have empathy. 'It’s not an escape [from the realities of life],' Shabazz insists, 'but a balance. Prospect Park has been a medicine for me too.'

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Prospect Park Photographs of a Brooklyn Oasis, 1980 to 2025 By Jamel Shabazz with contributions by Laylah Amatullah Barrayn, Richard E. Green, and Noelle Théard © 2025 Prestel Verlag, Munich · London · New York

Prospect Park, 1988

Josh Sims is a journalist contributing to the likes of The Times, Esquire and the BBC. He's the author of many books on style, including Retro Watches (Thames & Hudson).